Winchcombe

Winchcombe (/ˈwɪntʃkəm/) is a small medieval market town in the Cotswold hills of Gloucestershire, England. It lies halfway between Broadway and Cheltenham. The population was recorded as 4,538 in the 2011 census, and estimated at 5,347 in 2019.[1]

| Winchcombe | |

|---|---|

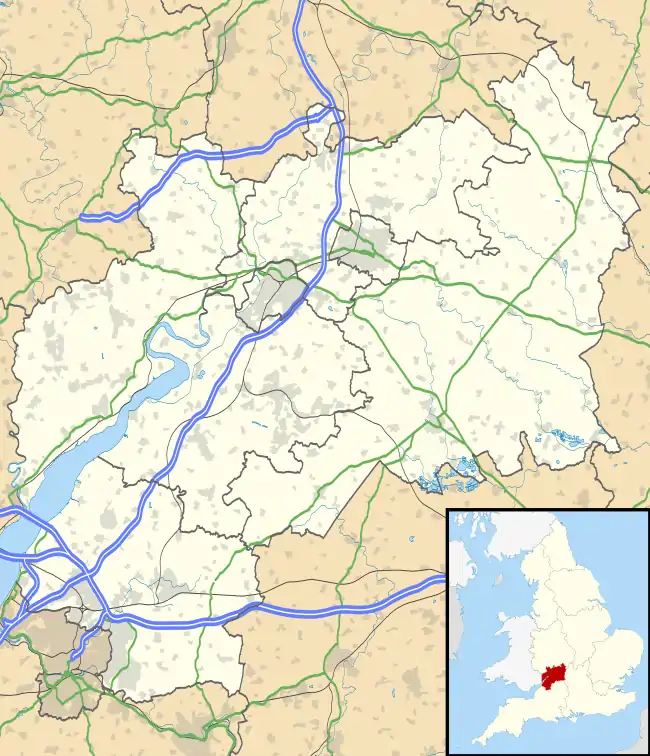

Winchcombe Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 4,538 |

| OS grid reference | SP025285 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CHELTENHAM |

| Postcode district | GL54 |

| Dialling code | 01242 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Attractions

Winchcombe started life as a Roman hamlet, rising to prominence as an Anglo-Saxon walled town with its own abbey, where a king and a saint are now buried. Although the town wall has long since vanished, Winchcombe retains much of its medieval layout, with a mix of timber framed[2] and Cotswold limestone buildings, some dating back to the 15th century, along its High Street.

Lying along The Cotswold Way, Winchcombe remains a popular destination for walkers and history fans alike. With people often visiting the running GWR steam train that connects it to Broadway and the Cheltenham Racecourse; and Sudeley Castle, the burial place of Queen Katherine Parr, that lies on its outskirts.

Early history

The Belas Knap Neolithic long barrow on Cleeve Hill above Winchcombe, dates from about 3000 BC.[3] In Anglo-Saxon times, Winchcombe was a major place in Mercia favoured by Coenwulf,[4] the others being Lichfield and Tamworth. In the 11th century, the town was briefly the county town of Winchcombeshire. The Anglo-Saxon saint St Kenelm is believed to be buried there.

During the Anarchy of the 12th century, a motte-and-bailey castle was erected in the early 1140s for the Empress Matilda, by Roger Fitzmiles, 2nd Earl of Hereford, but its exact site is unknown.[5] It has been suggested that it was to the south of St Peter's Church.

In the Restoration period, Winchcombe was noted for cattle rustling and other lawlessness, caused in part by poverty. In an attempt to earn a living, local people grew tobacco as a cash crop, though this practice had been outlawed since the Commonwealth period. Soldiers were sent in at least once to destroy the illegal crop.[6]

Notable buildings

In Winchcombe and its vicinity can be found Sudeley Castle and the remains of Hailes Abbey, once one of the main places of pilgrimage in England, due to a phial possessed by the monks that was said to contain the Blood of Christ.[7] Nothing remains of the former Winchcombe Abbey. St Peter's Church in the centre of the town is noted for its grotesques.

Winchcombe has a Michelin star restaurant at 5 North Street.[8]

Several buildings around Sudeley Hill are Grade II listed.[9]

Notable people

In birth order:

- Saint Kenelm (c. 786–811), a martyred boy-king of Mercia, was interred at Winchcombe, which became a major centre for his medieval cult.

- Robert Tideman of Winchcombe (died 1341) was consecrated Bishop of Llandaff in 1393 and translated to the see of Worcester in 1395.

- Ralph Boteler, 1st Baron Sudeley (c. 1394–1473), Lord High Treasurer of England and builder of Sudeley Castle and St. Peter's Church in Winchcombe.

- Giles Brydges, 3rd Baron Chandos (c. 1548–1594), an English courtier in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, was born and was buried at Sudeley Castle in Winchcombe.

- Grey Brydges, 5th Baron Chandos (c. 1580–1621), remembered as "King of the Cotswolds" for his wealth

- Clement Barksdale (1609–1687), born in Winchcombe, became a religious author, polymath and Anglican priest.

- Christopher Merret (1614/1615–1695), born in Winchcombe, a naturalist, produced the first lists of British birds and butterflies.

- Richard Eedes (died 1686), a Presbyterian minister and religious author with royalist sympathies, died at Winchcombe.

- Emma Dent (1823–1900), antiquarian, collector and author of The Annals of Winchcombe and Sudeley, restored Sudeley Castle with her husband and built or improved many houses in the town, including the Dent Almshouses.[10]

- George Backhouse Witts (1846–1912), a civil engineer and archaeologist who specialized in the barrows of Gloucestershire, was born in Winchcombe.

- Edward Griffiths (1862–1893) played cricket for Gloucestershire in 1885–1889.

- William Yiend (1865–1939), born in Winchcombe, was an international rugby union forward.

- John Alfred Valentine Butler (1899–1977), born in Winchcombe, was a physical chemist who contributed to electrode kinetics through the Butler–Volmer equation.

- Michael Cardew (1901–1983), master potter, moved to Winchcombe to revive a derelict pottery and 17th-century English slipware tradition.

- John Kingsley Cook (1911–1994), a prominent wood engraver, was born in Winchcombe.

- Ray Finch (1914–2012), master potter, bought Michael Cardew's pottery in 1939, and after the Second World War worked there for the rest of his life making stoneware.

- Colin Pearson (1923–2007), master potter, worked at Winchcombe under Ray Finch until 1954.

- Seth Cardew (1934–2016), a master potter born in Winchcombe, was the son of Michael Cardew and brother of the composer Cornelius Cardew.

- Cornelius Cardew (1936–1981), composer, was born in Winchcombe, the son of Michael Cardew.

Walks

Winchcombe is crossed by seven long-distance footpaths: The Cotswold Way, the Gloucestershire Way, the Wychavon Way, St Kenelm's Trail, St Kenelm's Way,[11] the Warden's Way and the Windrush Way. Winchcombe became a member of the Walkers are Welcome network of towns in July 2009 and now holds a walking festival every May.

Public transport

A bus service connects the town to Cheltenham, Broadway, Willersey and further afield on special services.[12]

Winchcombe was served by a railway line that was opened in 1906 by the Great Western Railway. It ran from Stratford-upon-Avon to Cheltenham, as part of a main line from Birmingham to the South West and South Wales. Winchcombe railway station and most others on the section closed in March 1960.[13] Through passenger services continued on the line until March 1968 and goods until 1976, when a derailment at Winchcombe damaged the line and it was decided not to bring the section back into use.[14] By the early 1980s it had been dismantled. The stretch between Toddington and Cheltenham Racecourse, including Winchcombe, has since been reconstructed and reopened as the heritage Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway.[15] It was extended to Broadway in spring 2018. A new station has been opened at Winchcombe on its original site, the building transferred there being the former (Troy) railway station.[16] Nearby is the 693-yard/634 m Greet Tunnel, the second longest on a preserved line in Britain.

Governance

An electoral ward in the same name exists. This ward stretches from Alderton in the north to Hawling in the south. The total ward population at the 2011 census was 6,295.[17]

Schools

Winchcombe has a primary school and a secondary school, Winchcombe School. The latter is in Greet Road, east of the town centre. Winchcombe Abbey Church of England Primary School lies near the town centre in Back Lane, next to Winchcombe Library and Cowl Lane.

Community

A community radio station called Radio Winchcombe launched in April 2005 began broadcasting for 20 days a year (10 days every 6 months).[18] Full-time broadcasting was approved in December 2011 by Ofcom,[19] and began on 18 May 2012.

Winchcombe Town F.C. plays in the Gloucestershire Northern Senior League.[20]

References

- City Population. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "GEORGE INN". Historic England. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "English Heritage. Retrieved 21 April 2020". Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, Michelle P. Brown, Carol A. Farr ISBN 0-8264-7765-8

- David Walker (1991) Gloucestershire Castles Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine in Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1991, Vol. 109, p. 15.

- Pepys's Diary, 19 September 1667.

- Sacred Destinations Archived 29 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Abbey site.

- Norman, Matthew (19 November 2013). "5 North St, Gloucestershire, restaurant review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- "Listed buildings in Winchcombe. Retrieved 22 May 2020". Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Dent, Emma (1877). Annals of Winchcombe and Sudeley. John Murray. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- "Long Distance Walkers Association guide". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- "606 - Chipping Campden - Willersey - Winchcombe - Bishop's Cleeve - Cheltenham". Bus Times. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Yeovil: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 251. ISBN 1852605081. R508.

- "Honeybourne Line". The Restoration & Archiving Trust. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Winchcombe". GWSR. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Winchcombe Station". GWSR. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Ward population 2011". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Winchcombe Radio". Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- "Ofcom awards four new community radio licences". Ofcom. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Gloucestershire Northern Senior League". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winchcombe. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Winchcombe. |

| Following the Cotswold Way | |

|---|---|

| Towards Bath | Towards Chipping Campden |

| 13.5 km (8.4 mi) to Cheltenham | 19 km (12 mi) to Broadway |