William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded his elder brother George IV, becoming the last king and penultimate monarch of Britain's House of Hanover.

William served in the Royal Navy in his youth, spending time in North America and the Caribbean, and was later nicknamed the "Sailor King".[1][2] In 1789, he was created Duke of Clarence and St Andrews. In 1827, he was appointed as Britain's first Lord High Admiral since 1709. As his two older brothers died without leaving legitimate issue, he inherited the throne when he was 64 years old. His reign saw several reforms: the poor law was updated, child labour restricted, slavery abolished in nearly all of the British Empire, and the British electoral system refashioned by the Reform Act 1832. Although William did not engage in politics as much as his brother or his father, he was the last monarch to appoint a British prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament. He granted his German kingdom a short-lived liberal constitution.

At the time of his death, William had no surviving legitimate children, but he was survived by eight of the ten illegitimate children he had by the actress Dorothea Jordan, with whom he cohabited for twenty years. Late in life, he married and apparently remained faithful to the young princess who would become Queen Adelaide. William was succeeded by his niece Queen Victoria in the United Kingdom, and his brother King Ernest Augustus in Hanover.

Early life

William was born in the early hours of the morning on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House, the third child and son of King George III and Queen Charlotte.[3] He had two elder brothers, George, Prince of Wales, and Frederick (later Duke of York), and was not expected to inherit the Crown. He was baptised in the Great Council Chamber of St James's Palace on 20 September 1765. His godparents were the King's siblings: Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh; Prince Henry (later Duke of Cumberland); and Princess Augusta, Hereditary Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.[4]

He spent most of his early life in Richmond and at Kew Palace, where he was educated by private tutors.[5] At the age of thirteen, he joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman,[6] and was present at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1780.[7] His experiences in the navy seem to have been little different from those of other midshipmen, though in contrast to other sailors he was accompanied on board ships by a tutor. He did his share of the cooking[8] and got arrested with his shipmates after a drunken brawl in Gibraltar; he was hastily released from custody after his identity became known.[9]

He served in New York during the American War of Independence, making him the only member of the British royal family to visit America up to and through the American Revolution. While William was in America, George Washington approved a plot to kidnap him, writing: "The spirit of enterprise so conspicuous in your plan for surprising in their quarters and bringing off the Prince William Henry and Admiral Digby merits applause; and you have my authority to make the attempt in any manner, and at such a time, as your judgment may direct. I am fully persuaded, that it is unnecessary to caution you against offering insult or indignity to the persons of the Prince or Admiral..."[10] The plot did not come to fruition; the British heard of it and assigned guards to William, who had until then walked around New York unescorted.[11] In September 1781, William held court at the Manhattan home of Governor Robertson. In attendance were Mayor David Mathews, Admiral Digby, and General Delancey.[12]

He became a lieutenant in 1785 and captain of HMS Pegasus the following year.[13] In late 1786, he was stationed in the West Indies under Horatio Nelson, who wrote of William: "In his professional line, he is superior to two-thirds, I am sure, of the [Naval] list; and in attention to orders, and respect to his superior officer, I hardly know his equal."[14] The two were great friends, and dined together almost nightly. At Nelson's wedding, William insisted on giving the bride away.[15] He was given command of the frigate HMS Andromeda in 1788, and was promoted to rear-admiral in command of HMS Valiant the following year.[16]

William sought to be made a duke like his elder brothers, and to receive a similar parliamentary grant, but his father was reluctant. To put pressure on him, William threatened to stand for the British House of Commons for the constituency of Totnes in Devon. Appalled at the prospect of his son making his case to the voters, George III created him Duke of Clarence and St Andrews and Earl of Munster on 16 May 1789,[17] supposedly saying: "I well know it is another vote added to the Opposition."[18] William's political record was inconsistent and, like many politicians of the time, cannot be certainly ascribed to a single party. He allied himself publicly with the Whigs, as did his elder brothers, who were known to be in conflict with the political positions of their father.[19]

Service and politics

William ceased his active service in the Royal Navy in 1790.[20] When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he was anxious to serve his country and expected a command, but was not given a ship, perhaps at first because he had broken his arm by falling down some stairs drunk, but later perhaps because he gave a speech in the House of Lords opposing the war.[21] The following year he spoke in favour of the war, expecting a command after his change of heart; none came. The Admiralty did not reply to his request.[22] He did not lose hope of being appointed to an active post. In 1798 he was made an admiral, but the rank was purely nominal.[23] Despite repeated petitions, he was never given a command throughout the Napoleonic Wars.[24] In 1811, he was appointed to the honorary position of Admiral of the Fleet. In 1813, he came nearest to any actual fighting, when he visited the British troops fighting in the Low Countries. Watching the bombardment of Antwerp from a church steeple, he came under fire, and a bullet pierced his coat.[25]

Instead of serving at sea, William spent time in the House of Lords, where he spoke in opposition to the abolition of slavery, which still existed in the British colonies. Freedom would do the slaves little good, he argued. He had travelled widely and, in his eyes, the living standard among freemen in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland was worse than that among slaves in the West Indies.[26] His experience in the Caribbean, where he "quickly absorbed the plantation owners' views about slavery",[27] lent weight to his position, which was perceived as well-argued and just by some of his contemporaries.[28] In his first speech before Parliament he called himself "an attentive observer of the state of the negroes" who found them well cared for and "in a state of humble happiness".[29] Others thought it "shocking that so young a man, under no bias of interest, should be earnest in continuance of the slave trade".[30] In his speech to the House, William insulted William Wilberforce, the leading abolitionist, saying: "the proponents of the abolition are either fanatics or hypocrites, and in one of those classes I rank Mr. Wilberforce".[31] On other issues he was more liberal, such as supporting moves to abolish penal laws against dissenting Christians.[32] He also opposed efforts to bar those found guilty of adultery from remarriage.[33]

Relationships and marriage

.jpg.webp)

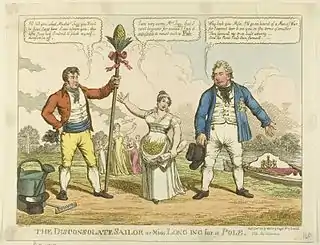

From 1791 William lived with an Irish actress, Dorothea Bland, better known by her stage name, Mrs. Jordan,[20] the title "Mrs." being assumed at the start of her stage career to explain an inconvenient pregnancy[34] and "Jordan" because she had "crossed the water" from Ireland to Britain.[35] He appeared to enjoy the domesticity of his life with Mrs. Jordan, remarking to a friend: "Mrs. Jordan is a very good creature, very domestic and careful of her children. To be sure she is absurd sometimes and has her humours. But there are such things more or less in all families." The couple, while living quietly, enjoyed entertaining, with Mrs. Jordan writing in late 1809: "We shall have a full and merry house this Christmas, 'tis what the dear Duke delights in."[36] George III was accepting of his son's relationship with the actress (though recommending that he halve her allowance);[37] in 1797, he created William the Ranger of Bushy Park, which included a large residence, Bushy House, for William's growing family.[38] William used Bushy as his principal residence until he became king.[39] His London residence, Clarence House, was constructed to the designs of John Nash between 1825 and 1827.[40]

The couple had ten illegitimate children—five sons and five daughters—nine of whom were named after William's siblings; each was given the surname "FitzClarence".[41][42] Their affair lasted for twenty years before ending in 1811. Mrs. Jordan had no doubt as to the reason for the break-up: "Money, money, my good friend, has, I am convinced made HIM at this moment the most wretched of men," adding, "With all his excellent qualities, his domestic virtues, his love for his lovely children, what must he not at this moment suffer?"[43] She was given a financial settlement of £4,400 (equivalent to £321,600 in 2019[44]) per year and custody of her daughters on condition that she did not resume the stage. When she resumed acting in an effort to repay debts incurred by the husband of one of her daughters from a previous relationship, William took custody of the daughters and stopped paying the £1,500 (equivalent to £105,700 in 2019[44]) designated for their maintenance. After Mrs. Jordan's acting career began to fail, she fled to France to escape her creditors, and died, impoverished, near Paris in 1816.[45]

Before he met Mrs. Jordan, William had an illegitimate son whose mother is unknown; the son, also called William, drowned off Madagascar in HMS Blenheim in February 1807.[46] Caroline von Linsingen, whose father was a general in the Hanoverian infantry, claimed to have had a son, Heinrich, by William in around 1790 but William was not in Hanover at the time that she claims and the story is considered implausible by historians.[47]

Deeply in debt, William made multiple attempts at marrying a wealthy heiress such as Catherine Tylney-Long, but his suits were unsuccessful.[48] Following the death of William's niece Princess Charlotte of Wales, then second-in-line to the British throne, in 1817, the king was left with twelve children, but no legitimate grandchildren. The race was on among the royal dukes to marry and produce an heir. William had great advantages in this race—his two older brothers were both childless and estranged from their wives, who were both beyond childbearing age anyway, and William was the healthiest of the three.[49] If he lived long enough, he would almost certainly ascend the British and Hanoverian thrones, and have the opportunity to sire the next monarch. William's initial choices of potential wives either met with the disapproval of his eldest brother, the Prince of Wales, or turned him down. His younger brother Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, was sent to Germany to scout out the available Protestant princesses; he came up with Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, but her father Frederick declined the match.[50] Two months later, the Duke of Cambridge married Augusta himself. Eventually, a princess was found who was amiable, home-loving, and was willing to accept, even enthusiastically welcoming William's nine surviving children, several of whom had not yet reached adulthood.[51] In the Drawing Room at Kew Palace on 11 July 1818, William married Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen.[52]

William's marriage, which lasted almost twenty years until his death, was a happy one. Adelaide took both William and his finances in hand. For their first year of marriage, the couple lived in economical fashion in Germany. William's debts were soon on the way to being paid, especially since Parliament had voted him an increased allowance, which he reluctantly accepted after his requests to have it increased further were refused.[53] William is not known to have had mistresses after his marriage.[16][54][55] The couple had two short-lived daughters and Adelaide suffered three miscarriages.[56] Despite this, false rumours that she was pregnant persisted into William's reign—he dismissed them as "damned stuff".[57]

Lord High Admiral

William's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, had been Prince Regent since 1811 because of the mental illness of their father. In 1820, the King died, leaving the Crown to the Prince Regent, who became George IV. William, Duke of Clarence, was now second in the line of succession, preceded only by his brother, Frederick, Duke of York. Reformed since his marriage, William walked for hours, ate relatively frugally, and the only drink he imbibed in quantity was barley water flavoured with lemon.[58] Both of his older brothers were unhealthy, and it was considered only a matter of time before he became king.[59] When Frederick died in 1827, William, then more than 60 years old, became heir presumptive. Later that year, the incoming Prime Minister, George Canning, appointed him to the office of Lord High Admiral, which had been in commission (that is, exercised by a board rather than by a single individual) since 1709. While in office, William had repeated conflicts with his Council, which was composed of Admiralty officers. Things finally came to a head in 1828 when, as Lord High Admiral, he put to sea with a squadron of ships, leaving no word of where they were going, and remaining away for ten days. The King requested his resignation through the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington; he complied.[54]

Despite the difficulties William experienced, he did considerable good as Lord High Admiral. He abolished the cat o' nine tails for most offences other than mutiny, attempted to improve the standard of naval gunnery, and required regular reports of the condition and preparedness of each ship. He commissioned the first steam warship and advocated more.[60] Holding the office permitted him to make mistakes and learn from them—a process that might have been far more costly if he had not learnt before becoming king that he should act only with the advice of his councillors.[54][61]

William spent the remaining time during his brother's reign in the House of Lords. He supported the Catholic Emancipation Bill against the opposition of his younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, describing the latter's position on the Bill as "infamous", to Cumberland's outrage.[62] George IV's health was increasingly bad; it was obvious by early 1830 that he was near death. The King took his leave of his younger brother at the end of May, stating, "God's will be done. I have injured no man. It will all rest on you then."[63] William's genuine affection for his older brother could not mask his rising anticipation that he would soon be king.[62][64]

Reign

Early reign

When King George IV died on 26 June 1830 without surviving legitimate issue, William succeeded him as King William IV. Aged 64, he was the oldest person yet to assume the British throne.[65] Unlike his extravagant brother, William was unassuming, discouraging pomp and ceremony. In contrast to George IV, who tended to spend most of his time in Windsor Castle, William was known, especially early in his reign, to walk, unaccompanied, through London or Brighton. Until the Reform Crisis eroded his standing, he was very popular among the people, who saw him as more approachable and down-to-earth than his brother.[66]

The King immediately proved himself a conscientious worker. The Prime Minister, Wellington, stated that he had done more business with King William in ten minutes than he had with George IV in as many days.[67] Lord Brougham described him as an excellent man of business, asking enough questions to help him understand the matter—whereas George IV feared to ask questions lest he display his ignorance and George III would ask too many and then not wait for a response.[68]

The King did his best to endear himself to the people. Charlotte Williams-Wynn wrote shortly after his accession: "Hitherto the King has been indefatigable in his efforts to make himself popular, and do good natured and amiable things in every possible instance."[69] Emily Eden noted: "He is an immense improvement on the last unforgiving animal, who died growling sulkily in his den at Windsor. This man at least wishes to make everybody happy, and everything he has done has been benevolent."[70]

William dismissed his brother's French chefs and German band, replacing them with English ones to public approval. He gave much of George IV's art collection to the nation, and halved the royal stud. George had begun an extensive (and expensive) renovation of Buckingham Palace; William refused to reside there, and twice tried to give the palace away, once to the Army as a barracks, and once to Parliament after the Houses of Parliament burned down in 1834.[71] His informality could be startling: when in residence at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, King William used to send to the hotels for a list of their guests and invite anyone he knew to dinner, urging guests not to "bother about clothes. The Queen does nothing but embroider flowers after dinner."[72]

Upon taking the throne, William did not forget his nine surviving illegitimate children, creating his eldest son Earl of Munster and granting the other children the precedence of a daughter or a younger son of a marquess. Despite this, his children importuned for greater opportunities, disgusting elements of the press who reported that the "impudence and rapacity of the FitzJordans is unexampled".[73] The relationship between William and his sons "was punctuated by a series of savage and, for the King at least, painful quarrels" over money and honours.[74] His daughters, on the other hand, proved an ornament to his court, as, "They are all, you know, pretty and lively, and make society in a way that real princesses could not."[75]

Reform crisis

At the time, the death of the monarch required fresh elections and, in the general election of 1830, Wellington's Tories lost ground to the Whigs under Lord Grey, though the Tories still had the largest number of seats. With the Tories bitterly divided, Wellington was defeated in the House of Commons in November, and Lord Grey formed a government. Grey pledged to reform the electoral system, which had seen few changes since the fifteenth century. The inequities in the system were great; for example, large towns such as Manchester and Birmingham elected no members (though they were part of county constituencies), while small boroughs, known as rotten or pocket boroughs—such as Old Sarum with just seven voters—elected two members of Parliament each. Often, the rotten boroughs were controlled by great aristocrats, whose nominees were invariably elected by the constituents—who were, most often, their tenants—especially since the secret ballot was not yet used in Parliamentary elections. Landowners who controlled seats were even able to sell them to prospective candidates.[76]

When the House of Commons defeated the First Reform Bill in 1831, Grey's ministry urged William to dissolve Parliament, which would lead to a new general election. At first, William hesitated to exercise his prerogative to dissolve Parliament because elections had just been held the year before and the country was in a state of high excitement which might boil over into violence. He was, however, irritated by the conduct of the Opposition, which announced its intention to move the passage of an Address, or resolution, in the House of Lords, against dissolution. Regarding the Opposition's motion as an attack on his prerogative, and at the urgent request of Lord Grey and his ministers, the King prepared to go in person to the House of Lords and prorogue Parliament.[77] The monarch's arrival would stop all debate and prevent passage of the Address.[78] When initially told that his horses could not be ready at such short notice, William is supposed to have said, "Then I will go in a hackney cab!"[78] Coach and horses were assembled quickly and he immediately proceeded to Parliament. Said The Times of the scene before William's arrival, "It is utterly impossible to describe the scene ... The violent tones and gestures of noble Lords ... astonished the spectators, and affected the ladies who were present with visible alarm."[79] Lord Londonderry brandished a whip, threatening to thrash the Government supporters, and was held back by four of his colleagues. William hastily put on the crown, entered the Chamber, and dissolved Parliament.[80] This forced new elections for the House of Commons, which yielded a great victory for the reformers. But although the Commons was clearly in favour of parliamentary reform, the Lords remained implacably opposed to it.[81]

The crisis saw a brief interlude for the celebration of the King's Coronation on 8 September 1831. At first, William wished to dispense with the coronation entirely, feeling that his wearing the crown while proroguing Parliament answered any need.[82] He was persuaded otherwise by traditionalists. He refused, however, to celebrate the coronation in the expensive way his brother had—the 1821 coronation had cost £240,000, of which £16,000 was merely to hire the jewels. At William's instructions, the Privy Council budgeted less than £30,000 for the coronation.[83] When traditionalist Tories threatened to boycott what they called the "Half Crown-nation",[84] the King retorted that they should go ahead, and that he anticipated "greater convenience of room and less heat".[85]

After the rejection of the Second Reform Bill by the House of Lords in October 1831, agitation for reform grew across the country; demonstrations grew violent in so-called "Reform Riots". In the face of popular excitement, the Grey ministry refused to accept defeat in the Lords, and re-introduced the Bill, which still faced difficulties in the Lords. Frustrated by the Lords' recalcitrance, Grey suggested that the King create a sufficient number of new peers to ensure the passage of the Reform Bill. The King objected—though he had the power to create an unlimited number of peers, he had already created 22 new peers in his Coronation Honours.[86] William reluctantly agreed to the creation of the number of peers sufficient "to secure the success of the bill".[87] However, the King, citing the difficulties with a permanent expansion of the peerage, told Grey that the creations must be restricted as much as possible to the eldest sons and collateral heirs of existing peers, so that the created peerages would eventually be absorbed as subsidiary titles. This time, the Lords did not reject the bill outright, but began preparing to change its basic character through amendments. Grey and his fellow ministers decided to resign if the King did not agree to an immediate and large creation to force the bill through in its entirety.[88] The King refused, and accepted their resignations. The King attempted to restore the Duke of Wellington to office, but Wellington had insufficient support to form a ministry and the King's popularity sank to an all-time low. Mud was slung at his carriage and he was publicly hissed. The King agreed to reappoint Grey's ministry, and to create new peers if the House of Lords continued to pose difficulties. Concerned by the threat of the creations, most of the bill's opponents abstained and the Reform Act 1832 was passed. The mob blamed William's actions on the influence of his wife and brother, and his popularity recovered.[89]

Foreign policy

William distrusted foreigners, particularly anyone French,[90] which he acknowledged as a "prejudice".[91] He also felt strongly that Britain should not interfere in the internal affairs of other nations, which brought him into conflict with the interventionist Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston.[92] William supported Belgian independence and, after unacceptable Dutch and French candidates were put forward, favoured Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the widower of his niece, Charlotte, as a candidate for the newly created Belgian throne.[93]

Though he had a reputation for tactlessness and buffoonery, William could be shrewd and diplomatic. He foresaw that the potential construction of a canal at Suez would make good relations with Egypt vital to Britain.[94] Later in his reign, he flattered the American ambassador at a dinner by announcing that he regretted not being "born a free, independent American, so much did he respect that nation, which had given birth to George Washington, the greatest man that ever lived".[95] By exercising his personal charm, William assisted in the repair of Anglo-American relations, which had been so deeply damaged during the reign of his father.[96]

King of Hanover

Public perception in Germany was that Britain dictated Hanoverian policy. This was not the case. In 1832, Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich introduced laws that curbed fledgling liberal movements in Germany. Lord Palmerston opposed this, and sought William's influence to cause the Hanoverian government to take the same position. The Hanoverian government instead agreed with Metternich, much to Palmerston's dismay, and William declined to intervene. The conflict between William and Palmerston over Hanover was renewed the following year when Metternich called a conference of the German states, to be held in Vienna, and Palmerston wanted Hanover to decline the invitation. Instead, William's brother Prince Adolphus, Viceroy of Hanover, accepted, backed fully by William.[97] In 1833, William signed a new constitution for Hanover, which empowered the middle class, gave limited power to the lower classes, and expanded the role of the parliament. The constitution was revoked after William's death by his brother, King Ernest Augustus.[98]

Later reign and death

For the remainder of his reign, William interfered actively in politics only once, in 1834, when he became the last British sovereign to choose a prime minister contrary to the will of Parliament. In 1834, the ministry was facing increasing unpopularity and Lord Grey retired; the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne, replaced him. Melbourne retained most Cabinet members, and his ministry retained an overwhelming majority in the House of Commons. Some members of the Government, however, were anathema to the King, and increasingly left-wing policies concerned him. The previous year Grey had already pushed through a bill reforming the Protestant Church of Ireland. The Church collected tithes throughout Ireland, supported multiple bishoprics and was wealthy. However, barely an eighth of the Irish population belonged to the Church of Ireland. In some parishes, there were no Church of Ireland members at all, but there was still a priest paid for by tithes collected from the local Catholics and Presbyterians, leading to charges that idle priests were living in luxury at the expense of the Irish living at the level of subsistence. Grey's bill had reduced the number of bishoprics by half, abolished some of the sinecures and overhauled the tithe system. Further measures to appropriate the surplus revenues of the Church of Ireland were mooted by the more radical members of the Government, including Lord John Russell.[99] The King had an especial dislike for Russell, calling him "a dangerous little Radical."[100]

In November 1834, the Leader of the House of Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord Althorp, inherited a peerage, thus removing him from the Commons to the Lords. Melbourne had to appoint a new Commons leader and a new Chancellor (who by long custom, must be drawn from the Commons), but the only candidate whom Melbourne felt suitable to replace Althorp as Commons leader was Lord John Russell, whom William (and many others) found unacceptable due to his radical politics. William claimed that the ministry had been weakened beyond repair and used the removal of Lord Althorp—who had previously indicated that he would retire from politics upon becoming a peer[101]—as the pretext for the dismissal of the entire ministry. With Lord Melbourne gone, William chose to entrust power to a Tory, Sir Robert Peel. Since Peel was then in Italy, the Duke of Wellington was provisionally appointed Prime Minister.[102] When Peel returned and assumed leadership of the ministry for himself, he saw the impossibility of governing because of the Whig majority in the House of Commons. Consequently, Parliament was dissolved to force fresh elections. Although the Tories won more seats than in the previous election, they were still in the minority. Peel remained in office for a few months, but resigned after a series of parliamentary defeats. Melbourne was restored to the Prime Minister's office, remaining there for the rest of William's reign, and the King was forced to accept Russell as Commons leader.[103]

The King had a mixed relationship with Lord Melbourne. Melbourne's government mooted more ideas to introduce greater democracy, such as the devolution of powers to the Legislative Council of Lower Canada, which greatly alarmed the King, who feared it would eventually lead to the loss of the colony.[104] At first, the King bitterly opposed these proposals. William exclaimed to Lord Gosford, Governor General-designate of Canada: "Mind what you are about in Canada ... mind me, my Lord, the Cabinet is not my Cabinet; they had better take care or by God, I will have them impeached."[105] When William's son Augustus FitzClarence enquired of his father whether the King would be entertaining during Ascot week, William gloomily replied, "I cannot give any dinners without inviting the ministers, and I would rather see the devil than any one of them in my house."[106] Nevertheless, William approved the Cabinet's recommendations for reform.[107] Despite his disagreements with Melbourne, the King wrote warmly to congratulate the Prime Minister when he triumphed in the adultery case brought against him concerning Lady Caroline Norton—he had refused to permit Melbourne to resign when the case was first brought.[108] The King and Prime Minister eventually found a modus vivendi; Melbourne applying tact and firmness when called for; while William realised that his First Minister was far less radical in his politics than the King had feared.[106]

Both the King and Queen were fond of their niece, Princess Victoria of Kent. Their attempts to forge a close relationship with the girl were frustrated by the conflict between the King and the Duchess of Kent, the Princess's widowed mother. The King, angered at what he took to be disrespect from the Duchess to his wife, took the opportunity at what proved to be his final birthday banquet in August 1836 to settle the score. Speaking to those assembled at the banquet, who included the Duchess and Princess, William expressed his hope that he would survive until the Princess was 18 so that the Duchess would never be regent. He said, "I trust to God that my life may be spared for nine months longer ... I should then have the satisfaction of leaving the exercise of the Royal authority to the personal authority of that young lady, heiress presumptive to the Crown, and not in the hands of a person now near me, who is surrounded by evil advisers and is herself incompetent to act with propriety in the situation in which she would be placed."[109] The speech was so shocking that Victoria burst into tears, while her mother sat in silence and was only with difficulty persuaded not to leave immediately after dinner (the two left the next day). William's outburst undoubtedly contributed to Victoria's tempered view of him as "a good old man, though eccentric and singular".[110] William survived, though mortally ill, to the month after Victoria's coming of age. "Poor old man!", Victoria wrote as he was dying, "I feel sorry for him; he was always personally kind to me."[111]

William was "very much shaken and affected" by the death of his eldest daughter, Sophia, Lady de L'Isle and Dudley, in childbirth in April 1837.[112] William and his eldest son, George, Earl of Munster, were estranged at the time, but William hoped that a letter of condolence from Munster signalled a reconciliation. His hopes were not fulfilled and Munster, still thinking he had not been given sufficient money or patronage, remained bitter to the end.[113]

Queen Adelaide attended the dying William devotedly, not going to bed herself for more than ten days.[114] William died in the early hours of the morning of 20 June 1837 at Windsor Castle, where he was buried. As he had no living legitimate issue, the Crown of the United Kingdom passed to Princess Victoria, the only child of the Duke of Kent, George III's fourth son. Under Salic Law, a woman could not rule Hanover, and so the Hanoverian Crown went to George III's fifth son, the Duke of Cumberland. William's death thus ended the personal union of Britain and Hanover, which had persisted since 1714. The main beneficiaries of his will were his eight surviving children by Mrs. Jordan.[54] Although William is not the direct ancestor of the later monarchs of the United Kingdom, he has many notable descendants through his illegitimate family with Mrs. Jordan, including former British Prime Minister David Cameron,[115] TV presenter Adam Hart-Davis, and author and statesman Duff Cooper.[116]

Legacy

William IV had a short but eventful reign. In Britain, the Reform Crisis marked the ascendancy of the House of Commons and the corresponding decline of the House of Lords, and the King's unsuccessful attempt to remove the Melbourne ministry indicated a reduction in the political influence of the Crown and of the King's influence over the electorate. During the reign of George III, the King could have dismissed one ministry, appointed another, dissolved Parliament, and expected the electorate to vote in favour of the new administration. Such was the result of a dissolution in 1784, after the dismissal of the Fox-North Coalition, and in 1807, after the dismissal of Lord Grenville. But when William dismissed the Melbourne ministry, the Tories under Sir Robert Peel failed to win the ensuing elections. The monarch's ability to influence the opinion of the electorate, and therefore national policy, had been reduced. None of William's successors has attempted to remove a government or to appoint another against the wishes of Parliament. William understood that as a constitutional monarch he had no power to act against the opinion of Parliament. He said, "I have my view of things, and I tell them to my ministers. If they do not adopt them, I cannot help it. I have done my duty."[117]

During William's reign the British Parliament enacted major reforms, including the Factory Act of 1833 (preventing child labour), the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (emancipating slaves in the colonies), and the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (standardising provision for the destitute).[16] William attracted criticism both from reformers, who felt that reform did not go far enough, and from reactionaries, who felt that reform went too far. A modern interpretation sees him as failing to satisfy either political extreme by trying to find compromise between two bitterly opposed factions, but in the process proving himself more capable as a constitutional monarch than many had supposed.[118][119]

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles and styles

- 21 August 1765 – 16 May 1789: His Royal Highness The Prince William Henry

- 16 May 1789 – 26 June 1830: His Royal Highness The Duke of Clarence and St Andrews

- 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837: His Majesty The King

Honours

British and Hanoverian honours[120]

- 5 April 1770: Knight of the Thistle

- 19 April 1782: Knight of the Garter

- 23 June 1789: Member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- 2 January 1815: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- 12 August 1815: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order

- 26 April 1827: Royal Fellow of the Royal Society

Foreign honours

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Prussia: 11 April 1814: Knight of the Black Eagle[121]

Kingdom of Prussia: 11 April 1814: Knight of the Black Eagle[121] Kingdom of France: 24 April 1814: Knight of the Holy Spirit[120]

Kingdom of France: 24 April 1814: Knight of the Holy Spirit[120] Russian Empire:[122]

Russian Empire:[122]

- 9 June 1814: Knight of St. Andrew

- 9 June 1814: Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky

Denmark: 15 July 1830: Knight of the Elephant[123]

Denmark: 15 July 1830: Knight of the Elephant[123].svg.png.webp) Baden:[124]

Baden:[124]

.svg.png.webp) Spain: 21 February 1834: Knight of the Golden Fleece[125]

Spain: 21 February 1834: Knight of the Golden Fleece[125] Württemberg: Knight Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown[126]

Württemberg: Knight Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown[126]

Arms

As a son of the sovereign, William was granted the use of the royal arms (without the electoral inescutcheon in the Hanoverian quarter) in 1781, differenced by a label of three points argent, the centre point bearing a cross gules, the outer points each bearing an anchor azure.[127] In 1801 his arms altered with the royal arms, however the marks of difference remained the same.

As king his arms were those of his two kingdoms, the United Kingdom and Hanover, superimposed: Quarterly, I and IV Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England); II Or a lion rampant within a tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland); III Azure a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland); overall an escutcheon tierced per pale and per chevron (for Hanover), I Gules two lions passant guardant Or (for Brunswick), II Or a semy of hearts Gules a lion rampant Azure (for Lüneburg), III Gules a horse courant Argent (for Westphalia), overall an inescutcheon Gules charged with the crown of Charlemagne Or, the whole escutcheon surmounted by a crown.[128]

|

.svg.png.webp) |

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|---|---|

| Coat of Arms from 1801 to 1830 as Duke of Clarence | Coat of arms of King William IV | Coat of arms of King William IV (in Scotland) |

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Dorothea Bland | |||

| George FitzClarence, 1st Earl of Munster | 29 January 1794 | 20 March 1842 | Married Mary Wyndham, had issue. Committed suicide aged 48. |

| Henry FitzClarence | 27 March 1795 | September 1817 | Died unmarried, aged 22. |

| Sophia FitzClarence | August 1796 | 10 April 1837 | Married Philip Sidney, 1st Baron De L'Isle and Dudley, and had issue. |

| Mary FitzClarence | 19 December 1798 | 13 July 1864 | Married Charles Richard Fox, no issue. |

| Lord Frederick FitzClarence | 9 December 1799 | 30 October 1854 | Married Lady Augusta Boyle, one surviving daughter. |

| Elizabeth FitzClarence | 17 January 1801 | 16 January 1856 | Married William Hay, 18th Earl of Erroll, had issue. |

| Lord Adolphus FitzClarence | 18 February 1802 | 17 May 1856 | Died unmarried. |

| Augusta FitzClarence | 17 November 1803 | 8 December 1865 | Married twice, had issue. |

| Lord Augustus FitzClarence | 1 March 1805 | 14 June 1854 | Married Sarah Gordon, had issue. |

| Amelia FitzClarence | 21 March 1807 | 2 July 1858 | Married Lucius Cary, 10th Viscount Falkland, had one son. |

| By Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen | |||

| Princess Charlotte Augusta Louisa of Clarence | 27 March 1819 | Died a few hours after being baptised, in Hanover.[42] | |

| Stillborn child | 5 September 1819 | Born dead at Calais[56] or Dunkirk.[42] | |

| Princess Elizabeth Georgiana Adelaide of Clarence | 10 December 1820 | 4 March 1821 | Born and died at St James's Palace.[42] |

| Stillborn twin boys | 8 April 1822 | Born dead at Bushy Park.[129] | |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of William IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Staff writer (25 January 1831). "Scots Greys". The Times. UK. p. 3.

...they will have the additional honour of attending our "Sailor King"...

- Staff writer (29 June 1837). "Will of his late Majesty William IV". The Times. UK. p. 5.

...ever since the accession of our sailor King...

- Ziegler, p. 12.

- "Royal Christenings". Yvonne's Royalty Home Page. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- Ziegler, pp. 13–19.

- Ziegler, pp. 23–31.

- Allen, p. 29 and Ziegler, p. 32.

- Ziegler, p. 29.

- Ziegler, p. 33.

- George Washington writing to Colonel Ogden, 28 March 1782, quoted in Allen, p. 31 and Ziegler, p. 39.

- Allen, p. 32 and Ziegler, p. 39.

- Sabine, William H. W., ed. (1956). Historical Memoirs of William Smith. III. New York: Arno Press. pp. 446–447.

- Ziegler, pp. 54–57.

- Ziegler, p. 59.

- Somerset, p. 42.

- Ashley, Mike (1998). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. London: Robinson. pp. 686–687. ISBN 978-1-84119-096-9.

- Ziegler, p. 70.

- Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel Wraxall, 1st Baronet, p. 154 quoted in Ziegler, p. 89.

- Allen, p. 46 and Ziegler, pp. 89–92.

- "William IV". Official web site of the British monarchy. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Ziegler, pp. 91–94.

- Ziegler, p. 94.

- Ziegler, p. 95.

- Ziegler, pp. 95–97.

- Ziegler, p. 115.

- Ziegler, p. 54.

- Hochschild, p. 186.

- Ziegler, pp. 97–99.

- Hochschild, p. 187.

- Zachary Macaulay writing to Miss Mills, 1 June 1799, quoted in Ziegler, p. 98.

- Fulford, p. 121.

- Ziegler, p. 99.

- Fulford, pp. 121–122.

- Van der Kiste, p. 51.

- Allen, p. 49 and Ziegler, p. 76.

- Fulford, p. 125.

- Ziegler, pp. 80–81.

- Somerset, p. 68.

- Allen, pp. 52–53 and Ziegler, p. 82.

- "Royal Residences: Clarence House". Official web site of the British monarchy. 4 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Ziegler, p. 296.

- Weir, pp. 303–304.

- Somerset, pp. 78–79.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Ziegler, pp. 108–109.

- William writing to Lord Collingwood, 21 May 1808, quoted in Ziegler, p. 83.

- Allen, p. 36 and Ziegler, p. 50.

- Ziegler, pp. 99–100.

- Ziegler, p. 118.

- Letter from Hesse to the Duke of Cambridge, 1 March 1818, quoted in Ziegler, p. 121.

- Ziegler, p. 121.

- The Times, Monday, 13 July 1818 p. 3 col.A

- Ziegler, pp. 121–129.

- Brock, Michael (2004) "William IV (1765–1837)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29451. Retrieved 6 July 2007 (subscription required)

- Allen, p. 87.

- Ziegler, p. 126.

- Ziegler, p. 268.

- Ziegler, p. 130.

- Molloy, p. 9.

- Ziegler, p. 141.

- Ziegler, p. 133.

- Ziegler, p. 143.

- Fulford, p. 137.

- Allen, pp. 77–78.

- Ashley, p. 3.

- Allen, pp. 83–86; Ziegler, pp. 150–154.

- Van der Kiste, p. 179.

- Somerset, p. 122.

- Somerset, p. 110.

- Van der Kiste, p. 178.

- Somerset, p. 110–122.

- Somerset, p. 119f.

- Morning Post quoted in Ziegler, p. 158.

- Ziegler, pp. 158–159.

- Somerset, p. 117.

- Ziegler, pp. 177–180.

- Ziegler, pp. 182–188.

- Ziegler, p. 188.

- Grant, p. 59, quoting The Times

- Allen, pp. 121–122 and Ziegler, p. 189.

- Allen, pp. 124–127; Ziegler, p. 190f.

- Allen, pp. 124, 130; Ziegler, pp. 189, 192.

- Molloy, pp. 72–73.

- Allen, p. 130 and Ziegler, p. 193.

- Sir Herbert Taylor, the King's secretary, writing to Lord Grey, 15 August 1831, quoted in Ziegler, p. 194.

- Allen, p. 132.

- Correspondence of Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, with William IV and Sir Herbert Taylor, edited by Henry Grey, 3rd Earl Grey, (1867) 2.102, 113, quoted in Brock

- Allen, pp. 137–141; Ziegler, pp. 196–212.

- Ziegler, pp. 214–222.

- Allen, p. 205; Ziegler, p. 223.

- Sir Herbert Taylor writing to Lord Grey, 1 May 1832, quoted in Ziegler, p. 224.

- Ziegler, p. 225.

- Ziegler, p. 227.

- William writing to Palmerston, 1 June 1833, quoted in Ziegler, p. 234.

- Ziegler, p. 292.

- Allen, p. 229.

- Ziegler, p. 230f.

- Brophy, James M. (2010). "Hanover and Göttingen, 1837". Victorian Review. 36 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1353/vcr.2010.0041. JSTOR 41039097. S2CID 153563169.

- Ziegler, pp. 242–255.

- Molloy, p. 326.

- Somerset, p. 187.

- Ziegler, pp. 256–257.

- Ziegler, pp. 261–267.

- Ziegler, p. 274.

- Somerset, p. 202.

- Somerset, p. 200.

- Allen, pp. 221–222.

- Somerset, p. 204.

- Somerset, p. 209.

- Allen, p. 225.

- Victoria writing to Leopold, 19 June 1837, quoted in Ziegler, p. 290.

- Sir Herbert Taylor quoted in Ziegler, p. 287.

- Ziegler, p. 287.

- Ziegler, p. 289.

- Price, Andrew (5 December 2005). "Cameron's royal link makes him a true blue". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Barratt, Nick (5 January 2008). "Family detective: Adam Hart-Davis". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Recollections of John Hobhouse, 1st Baron Broughton, quoted in Ziegler, p. 276.

- Fulford, Roger (1967). "William IV". Collier's Encyclopedia. 23. p. 493.

- Ziegler, pp. 291–294.

- Cokayne, G.E.; Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. A. (1913). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, London: St. Catherine's Press, Vol. III, p. 261.

- Liste der Ritter des Königlich Preußischen Hohen Ordens vom Schwarzen Adler (1851), "Von Seiner Majestät dem Könige Friedrich Wilhelm III. ernannte Ritter" p. 17

- Almanach de la cour: pour l'année ... 1817. l'Académie Imp. des Sciences. 1817. pp. 63, 78.

- Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 207. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1834), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 32, 50

- "Caballeros existentes en la insignie Orden del Toison de Oro". Guía de forasteros en Madrid para el año de 1835 (in Spanish). En la Imprenta Nacional. 1835. p. 73.

- Königlich-Württembergisches Hof- und Staats-Handbuch: 1831. Guttenberg. 1831. p. 26.

- "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family". Heraldica.

- Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974). The Royal Heraldry of England. Heraldry Today. Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-900455-25-4.

- Ziegler, pp. 126–127.

- Weir, pp. 277–278.

- Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 5.

Sources

- Allen, W. Gore (1960). King William IV. London: Cresset Press.

- Brock, Michael (2004) "William IV (1765–1837)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29451. Retrieved 6 July 2007 (subscription required).

- Fulford, Roger (1973). Royal Dukes. London: Collins. (rev. ed.)

- Grant, James (1836). Random Recollections of the House of Lords. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Hochschild, Adam (2005). Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Molloy, Fitzgerald (1903). The Sailor King: William the Fourth, His Court and His Subjects. London: Hutchinson & Co. (2 vol.)

- Somerset, Anne (1980). The Life and Times of William IV. London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-83225-6.

- Van der Kiste, John (1994). George III's Children. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

- Weir, Alison (1996). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy, Revised edition. Random House. ISBN 978-0-7126-7448-5.

- Ziegler, Philip (1971). King William IV. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-211934-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William IV of the United Kingdom. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William IV |

- William IV at the official website of the British monarchy

- Digitised private and official papers of William IV at the Royal Collection

- William IV at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Works related to William IV at Wikisource

Works related to William IV at Wikisource

William IV Cadet branch of the House of Welf Born: 21 August 1765 Died: 20 June 1837 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George IV |

King of the United Kingdom 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837 |

Succeeded by Victoria |

| King of Hanover 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837 |

Succeeded by Ernest Augustus | |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by The Viscount Melville as First Lord of the Admiralty |

Lord High Admiral 1827–1828 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Melville as First Lord of the Admiralty |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of York and Albany |

Great Master of the Order of the Bath 1827–1830 |

Vacant Title next held by The Duke of Sussex |

.svg.png.webp)