Virginia-class battleship

The Virginia class of pre-dreadnought battleships were built for the United States Navy in the early 1900s. The class comprised five ships: Virginia, Nebraska, Georgia, New Jersey, and Rhode Island. The ships carried a mixed-caliber offensive battery of four 12-inch (305 mm) and eight 8-inch (203 mm) guns; these were mounted in an uncommon arrangement, with four of the 8-inch guns placed atop the 12-inch turrets. The arrangement proved to be a failure, as the 8-inch guns could not be fired independently of the 12-inch guns without interfering with them. Additionally, by the time the Virginias entered service, the first "all-big-gun" battleships—including the British HMS Dreadnought—were nearing completion, which would render mixed battery ships like the Virginia class obsolescent.

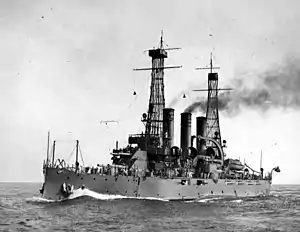

USS Virginia (BB-13) c. 1910–1913 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Virginia class |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Maine class |

| Succeeded by: | Connecticut class |

| Built: | 1902–1907 |

| In commission: | 1906–1920 |

| Completed: | 5 |

| Retired: | 5 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 441 ft 3 in (134 m) |

| Beam: | 76 ft 3 in (23 m) |

| Draft: | 23 ft 9 in (7 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 19 kn (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Complement: | 812 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Nevertheless, the ships had active careers. All five ships took part in the cruise of the Great White Fleet in 1907–1909. From 1909 onward, they served as the workhorses of the US Atlantic Fleet, conducting training exercises and showing the flag in Europe and Central America. As unrest broke out in several Central American countries in the 1910s, the ships became involved in police actions in the region. The most significant was the American intervention in the Mexican Revolution during the occupation of Veracruz in April 1914.

During the American participation in World War I, the Virginia-class ships were used to train sailors for an expanding wartime fleet. In September 1918, they began to escort convoys to Europe, though Germany surrendered two months later, ending the conflict. After the war, they were used to bring American soldiers back from France and later as training ships. The 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, which mandated major reductions in naval weapons, cut the ships' careers short. Virginia and New Jersey were sunk in bombing tests in 1923, and the other three ships were broken up for scrap later that year.

Design

The United States' victory in the Spanish–American War in 1898 had a dramatic impact on battleship design, as the question of the role of the fleet—namely, whether it should be focused on coastal defense or high seas operations—had been solved. The fleet's ability to conduct offensive operations overseas showed the necessity of a powerful fleet of battleships. As a result, the US Congress was willing to authorize much larger ships; the Virginias, three of which were authorized on 3 March 1899, were the first of these new ships. Two more were authorized on 7 June 1900, with the displacement for all five ships proposed at 13,500 long tons (13,700 t), a significant increase over previous designs. Initial design work, which began with a memorandum issued on 12 July 1898, called for a battleship based on the Maine class, to be armed with four 12-inch guns, sixteen 6-inch (152 mm) guns, and ten 3-inch (76 mm) guns, protected with a 12 in belt of Krupp armor, and capable of steaming at 18.5 knots (34.3 km/h; 21.3 mph).[1]

Arguments over the projected displacement and armament prevented further work until October 1899. Captain Charles O'Neill argued for a mixed battery of 12 in and 8 in (203 mm) guns with superposed turrets, while Phillip Hichborn, the chief constructor at the Bureau of Construction and Repair, preferred a 13,000-long-ton (13,000 t) design armed uniformly with 10 in (254 mm) guns instead of the mixed battery. The decision was made to adopt the mixed battery, since the 8 in gun could penetrate the medium armor on foreign battleships that protected their secondary batteries. Captain Royal Bradford, the chief of the Bureau of Equipment, suggested that 18.5 knots would be sufficient, though O'Neill demanded 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph); a compromise was found by requiring a minimum of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). These compromises produced two variants: "A", which arranged the 8 in guns in four twin turrets amidships as with the Indiana class, and "B", which placed two of the four turrets atop the 12 in turrets, as on the Kearsarge class. The "A" design included sixteen 6 in guns in casemates, while "B" had only twelve.[1]

The Board on Construction initially favored "A", though one officer on the board rejected the design so strongly that the Secretary of the Navy ordered a second, larger board to be formed to examine the two designs. Eight line officers were added to the board; this group favored the superposed turrets of "B". One of the members, Rear Admiral Albert Barker, suggested to build the first three ships to "A" and the last two to "B". The board initially approved the idea, but the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance rejected it in favor of uniformity of design. The Secretary of the Navy convened a third board to settle the matter, and ten of the twelve members voted for "B". The finalized design was approved on 5 February 1901.[1]

The superposed turrets ultimately proved to be very problematic; the arrangement had been conceived initially to save weight and allow the much faster firing 8 in guns to shoot during the long reload time necessary for large caliber guns. By the time the Virginias entered service, smokeless propellant and rapid firing, large caliber guns had reduced the time between shots from 180 seconds to 20. The 8 in guns could no longer fire at their maximum rate without interfering with the 12 in guns, since the concussion and hot gasses would disrupt the crew below. In addition, the British HMS Dreadnought—the first "all-big-gun" battleship to enter service—commissioned in late 1906 shortly after the Virginias and rendered them obsolescent at a single stroke.[2]

General characteristics and machinery

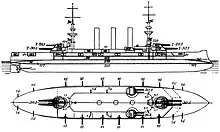

The ships of the Virginia class were 435 feet (133 m) long at the waterline and 441 feet 3 inches (134.49 m) long overall. They had a beam of 76 ft 3 in (23.24 m) and a draft of 23 ft 9 in (7.24 m). They displaced 14,948 long tons (15,188 t) as designed and up to 16,094 long tons (16,352 t) at full load. The ships had a high metacentric height, which made them unstable even in moderate seas. Steering was controlled with a single rudder. As built, the ships were fitted with a pair of heavy military masts with fighting tops, but they were replaced by cage masts in 1909. They had a crew of 40 officers and 772 enlisted men.[3][4]

The ship was powered by two-shaft triple-expansion steam engines rated at 19,000 indicated horsepower (14,000 kW). Steam was provided by coal-fired water-tube boilers; in Virginia and Georgia, they were equipped with twenty-four Niclausse boilers, while the other three ships received twelve Babcock & Wilcox boilers. These were trunked into three funnels amidships. The engines generated a top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). By 1919, Virginia and Georgia had their Niclausse boilers replaced with twelve Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The ships carried 1,955 long tons (1,986 t) of coal, which allowed them to steam for a designed cruising radius of 3,825 nautical miles (7,084 km; 4,402 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). In service, they could actually steam for 4,860 nmi (9,000 km; 5,590 mi). The ships were equipped with electricity generators with a combined output of 500 kilowatts (670 hp).[3][5]

Armament

The ships were armed with a main battery of four 12-inch/40 caliber[lower-alpha 1] guns in two twin gun turrets on the centerline, one forward and aft.[3] The guns fired a 870-pound (390 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,400 feet per second (730 m/s). The turrets were Mark V mounts, which allowed for reloading at all angles of elevation. These mounts could elevate to 20 degrees and depress to −7 degrees. Each gun was supplied with sixty shells.[6]

The secondary battery consisted of eight 8-inch/45 caliber Mark 6 guns and twelve 6-inch/50 caliber Mark 6 guns. The 8-inch guns were mounted in four twin turrets; two of these were superposed atop the main battery turrets, with the other two turrets abreast the forward funnel.[3] The 8-inch guns were the Mark VI type, and they fired 260 lb (120 kg) shells at a muzzle velocity of 2,750 ft/s (840 m/s).[3][7] They were supplied with 125 shells per gun.[8] The 6-inch guns were placed in casemates in the hull. The 6-inch Mark VI guns fired a 105 lb (48 kg) shell at 2,800 ft/s (850 m/s).[9]

For close-range defense against torpedo boats, they carried twelve 3-inch/50 caliber guns mounted in casemates along the side of the hull and twelve 3-pounder guns. As was standard for capital ships of the period, the Virginia class carried four 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, submerged in her hull on the broadside.[3] They were initially equipped with the Mark I Bliss-Leavitt design, but these were quickly replaced with Mark II, designed in 1905. The Mark II carried a 207-pound (94 kg) warhead and had a range of 3,500 yards (3,200 m) at a speed of 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph).[10]

Armor

Virginia's main armored belt was 11 in (279 mm) thick over the magazines and the machinery spaces and 8 in (203 mm) elsewhere. It extended 3 feet (0.91 m) above the waterline and 5 feet (1.5 m) below. The main battery gun turrets (and the secondary turrets on top of them) had 12-inch (305 mm) thick faces and 2 in (51 mm) thick roofs. For the main battery turrets, their sides were 8 in thick, while the superposed turrets had reduced protection on their sides, at 6 in of armor plating. The supporting barbettes had the 10 in (254 mm) of armor plating. The two waist turrets had 6.5 in (170 mm) thick faces, 6 in thick sides, and 2 in thick roofs. Six inch thick armor plating protected the casemate guns. The conning tower had 9 in (230 mm) thick sides and a 2 in thick roof. The ships' decks ranged in thickness from 1.5 to 3 inches (38 to 76 mm) and they were sloped on the sides to connect with the lower edge of the main belt.[3][5]

Construction

| Name | Builder[3] | Laid down[3] | Launched[3] | Commissioned[3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USS Virginia (BB-13) | Newport News Shipbuilding Company | 21 May 1902 | 5 April 1904 | 7 May 1906 |

| USS Nebraska (BB-14) | Moran Brothers Shipyard | 4 July 1902 | 7 October 1904 | 1 July 1907 |

| USS Georgia (BB-15) | Bath Iron Works | 31 August 1901 | 11 October 1904 | 24 September 1906 |

| USS New Jersey (BB-16) | Fore River Shipyard | 3 May 1902 | 10 November 1904 | 12 May 1906 |

| USS Rhode Island (BB-17) | Fore River Shipyard | 1 May 1902 | 17 May 1904 | 19 February 1906 |

Service history

All five ships of the class served with the Atlantic Fleet for the majority of their careers. In 1907, Virginia, Georgia, and New Jersey took part in the Jamestown Exposition to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown colony. The five ships took part in the cruise of the Great White Fleet in 1907–09, though Nebraska, which had been built on the west coast of the United States, joined the fleet after it had reached California in 1908.[lower-alpha 2] The fleet left Hampton Roads on 16 December 1907 and steamed south, around South America and back north to the US west coast. The ships then crossed the Pacific and stopped in Australia, the Philippines, and Japan before continuing on through the Indian Ocean. They transited the Suez Canal and toured the Mediterranean before crossing the Atlantic, arriving bank in Hampton Roads on 22 February 1909 for a naval review with President Theodore Roosevelt.[16]

The ships then began a peacetime training routine off the east coast of the United States and the Caribbean, including gunnery training off the Virginia Capes, training cruises in the Atlantic, and winter exercises in Cuban waters. In late 1909, Virginia, Georgia, and Rhode Island visited French and British ports. Throughout their careers, political unrest in several Central American countries prompted the United States to send the ships to protect American interests in the region. New Jersey was sent to Cuba to assist the Cuban Pacification in support of the government of President Tomás Estrada Palma. All five ships became involved in the Mexican Revolution as the United States intervened to protect its nationals living in the country, culminating in the occupation of Veracruz in April 1914. New Jersey was also sent to protect American interests in Haiti and the Dominican unrest in 1914.[lower-alpha 2]

In July 1914, World War I broke out in Europe; the United States remained neutral for the first three years of the war. Tensions with Germany came to a head in early 1917 following the German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign, which sank several American merchant ships in European waters. On 6 April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. The Virginia-class ships initially were used for training gunners and engine room personnel that would be necessary for the rapidly expanding wartime fleet. Starting in September 1918, the ships began to be used as escorts for convoys bringing soldiers to France, though this duty was cut short by the Armistice with Germany signed in November. With the war over, the Virginias were used to ferry American soldiers back from France through mid-1919.[lower-alpha 2][17]

The ships—thoroughly obsolete by this time—were briefly retained in the post-war period before being decommissioned. Nebraska, Georgia, and Rhode Island were transferred to the Pacific Fleet, with the latter serving as the flagship of the 1st Squadron, though they were all out of service by 1920. Under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, signed in 1922, they were to be discarded as part of the naval armament limitation program.[lower-alpha 2] Virginia and New Jersey were sunk as target ships off Cape Hatteras by Army bombers under the supervision of Billy Mitchell in September 1923.[18] The other three ships were sold to ship breakers in November that year.[lower-alpha 2]

Footnotes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Virginia class battleships. |

Notes

Citations

- Friedman 1985, p. 42.

- Friedman 1985, p. 43.

- Gardiner, p. 143.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 43, 429.

- Friedman 1985, p. 429.

- Friedman 2011, pp. 168–169.

- Friedman 2011, pp. 177–178.

- Friedman 2011, p. 169.

- Friedman 2011, pp. 180–181.

- Friedman 2011, p. 342.

- DANFS Virginia.

- DANFS Nebraska.

- DANFS Georgia.

- DANFS New Jersey.

- DANFS Rhode Island.

- Albertson, pp. 41–66.

- Jones, p. 122.

- Wildenberg, pp. 112–114.

References

- Albertson, Mark (2007). U.S.S. Connecticut: Constitution State Battleship. Mustang: Tate Publishing. ISBN 1-59886-739-3.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1. OCLC 12214729.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- "Georgia (BB-15)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 3 April 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Jones, Jerry W. (1998). U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-411-3.

- "Nebraska". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "New Jersey (BB-16) i". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 16 April 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "Rhode Island (BB-17) ii". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "Virginia". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Wildenberg, Thomas (2014). Billy Mitchell's War with the Navy: The Army Air Corps and the Challenge to Seapower. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781612513324.