HMS Dreadnought (1906)

HMS Dreadnought was a Royal Navy battleship that revolutionised naval power. The name of the ship, and the class of battleships named after her, means "fear nothing".[1] Dreadnought's entry into service in 1906 represented such an advance in naval technology that her name came to be associated with an entire generation of battleships, the "dreadnoughts", as well as the class of ships named after her. Likewise, the generation of ships she made obsolete became known as "pre-dreadnoughts". Admiral Sir John "Jacky" Fisher, First Sea Lord of the Board of Admiralty, is credited as the father of Dreadnought. Shortly after he assumed office, he ordered design studies for a battleship armed solely with 12 in (305 mm) guns and a speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). He convened a "Committee on Designs" to evaluate the alternative designs and to assist in the detailed design work.

Dreadnought at sea in 1906 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Dreadnought |

| Preceded by: | Lord Nelson class |

| Succeeded by: | Bellerophon class |

| Cost: | £1,785,683 |

| Built: | 1905–1906 |

| In service: | 1906–1919 |

| In commission: | 1906–1919 |

| Completed: | 1 |

| Scrapped: | 1 |

| History | |

| Name: | Dreadnought |

| Ordered: | 1905 |

| Builder: | HM Dockyard, Portsmouth |

| Laid down: | 2 October 1905 |

| Launched: | 10 February 1906 |

| Commissioned: | 2 December 1906 |

| Decommissioned: | February 1919 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, 9 May 1921 |

| General characteristics (as completed) | |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 527 ft (160.6 m) |

| Beam: | 82 ft 1 in (25.0 m) |

| Draught: | 29 ft 7.5 in (9.0 m) (deep load) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 6,620 nmi (12,260 km; 7,620 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 700–810 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

Dreadnought was the first battleship of her era to have a uniform main battery, rather than having a few large guns complemented by a heavy secondary armament of smaller guns. She was also the first capital ship to be powered by steam turbines, making her the fastest battleship in the world at the time of her completion.[2] Her launch helped spark a naval arms race as navies around the world, particularly the German Imperial Navy, rushed to match it in the build-up to the First World War.[3]

Ironically for a vessel designed to engage enemy battleships, her only significant action was the ramming and sinking of German submarine SM U-29, becoming the only battleship confirmed to have sunk a submarine.[4] Dreadnought did not participate in the Battle of Jutland in 1916 as she was being refitted. Nor did Dreadnought participate in any of the other First World War naval battles. In May 1916 she was relegated to coastal defence duties in the English Channel, not rejoining the Grand Fleet until 1918. The ship was reduced to reserve in 1919 and sold for scrap two years later.

Genesis

Background

Gunnery developments in the late 1890s and the early 1900s, led in the United Kingdom by Percy Scott and in the United States by William Sims, were already pushing expected battle ranges out to an unprecedented 6,000 yd (5,500 m), a distance great enough to force gunners to wait for the shells to arrive before applying corrections for the next salvo. A related problem was that the shell splashes from the more numerous smaller weapons tended to obscure the splashes from the bigger guns. Either the smaller-calibre guns would have to hold their fire to wait for the slower-firing heavies, losing the advantage of their faster rate of fire, or it would be uncertain whether a splash was due to a heavy or a light gun, making ranging and aiming unreliable. Another problem was that longer-range torpedoes were expected to soon be in service and these would discourage ships from closing to ranges where the smaller guns' faster rate of fire would become preeminent. Keeping the range open generally negated the threat from torpedoes and further reinforced the need for heavy guns of a uniform calibre.[5]

In 1903, the Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti first articulated in print the concept of an all-big-gun battleship. When the Italian Navy did not pursue his ideas, Cuniberti wrote an article in Jane's Fighting Ships advocating his concept. He proposed an "ideal" future British battleship of 17,000 long tons (17,000 t), with a main battery of a dozen 12-inch guns in eight turrets, 12 inches of belt armour, and a speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph).[6]

The Royal Navy (RN), the Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States Navy all recognised these issues before 1905. The RN modified the design of the Lord Nelson-class battleship to include a secondary armament of 9.2 in (234 mm) guns that could fight at longer ranges than the 6 in (152 mm) guns on older ships, but a proposal to arm them solely with 12-inch guns was rejected.[7][Note 1] The Japanese battleship Satsuma was laid down as an all-big-gun battleship, five months before Dreadnought, but gun shortages allowed her to be equipped with only four of the twelve 12-inch guns that had been planned.[8] The Americans began design work on an all-big-gun battleship around the same time in 1904, but progress was leisurely and the two South Carolina-class battleships were not ordered until March 1906, five months after Dreadnought was laid down, and the month after she was launched.[9]

The invention by Charles Algernon Parsons of the steam turbine in 1884 led to a significant increase in the speed of ships with his dramatic unauthorised demonstration of Turbinia with her speed of up to 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) at Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee at Spithead in 1897. After further trials of two turbine-powered destroyers, Viper and Cobra, coupled with the positive experiences of several small passenger liners with turbines, Dreadnought was ordered with turbines.[10]

The Battle of the Yellow Sea and Battle of Tsushima were analysed by Fisher's Committee, with Captain William Pakenham's statement that "12-inch gunfire" by both sides demonstrated hitting power and accuracy, whilst 10-inch shells passed unnoticed.[11] Admiral Fisher wanted his board to confirm, refine and implement his ideas of a warship that had both the speed of 21 knots (39 km/h) and 12-inch guns,[12] pointing out that at the Battle of Tsushima, Admiral Togo had been able to cross the Russians' "T" due to speed.[13] The unheard of long-range (13,000 metres (14,000 yd))[14] fire during the Battle of the Yellow Sea, in particular, although never experienced by any navy prior to the battle, seemed to confirm what the RN already believed.[15]

Development

_profile_drawing.png.webp)

Admiral Fisher proposed several designs for battleships with a uniform armament in the early 1900s, and he gathered an unofficial group of advisors to assist him in deciding on the ideal characteristics in early 1904. After he was appointed First Sea Lord on 21 October 1904, he pushed through the Board of Admiralty a decision to arm the next battleship with 12 inch guns and that it would have a speed no less than 21 knots (39 km/h). In January 1905, he convened a "Committee on Designs", including many members of his informal group, to evaluate the various design proposals and to assist in the detailed design process. While nominally independent it served to deflect criticism of Fisher and the Board of Admiralty as it had no ability to consider options other than those already decided upon by the Admiralty. Fisher appointed all of the members of the committee and he was President of the Committee.[16]

The committee decided on the layout of the main armament, rejecting any superfiring arrangements because of concerns about the effects of muzzle blast on the open sighting hoods on the turret roof below, and chose turbine propulsion over reciprocating engines to save 1,100 long tons (1,100 t) in total displacement on 18 January 1905. Before disbanding on 22 February, it decided on a number of other issues, including the number of shafts (up to six were considered), the size of the anti-torpedo boat armament,[17] and most importantly, to add longitudinal bulkheads to protect the magazines and shell rooms from underwater explosions. This was deemed necessary after the Russian battleship Tsesarevich was thought to have survived a Japanese torpedo hit during the Russo–Japanese War by virtue of her heavy internal bulkhead. To avoid increasing the displacement of the ship, the thickness of her waterline belt was reduced by 1 in (25 mm).[18]

The Committee completed its deliberations on 22 February 1905 and reported their findings in March of that year. It was decided due to the experimental nature of the design to delay placing orders for any other ships until Dreadnought and her trials had been completed. Once the design had been finalised the hull form was designed and tested at the Admiralty's experimental ship tank at Gosport. Seven iterations were required before the final hull form was selected. Once the design was finalized, a team of three assistant engineers and 13 draughtsmen produced detailed drawings.[19]

To assist in speeding up the ship's construction, the internal hull structure was simplified as much as possible and an attempt was made to standardize on a limited number of standard plates, which varied only in their thickness.

Description

Overview

Dreadnought was significantly larger than the two ships of the Lord Nelson class, which were under construction at the same time. She had an overall length of 527 ft (160.6 m), a beam of 82 ft 1 in (25.0 m), and a draught of 29 ft 7.5 in (9.0 m) at deep load. She displaced 18,120 long tons (18,410 t) at normal load and 20,730 long tons (21,060 t) at deep load, almost 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) more than the earlier ships.[20] She had a metacentric height of 5.6 ft (1.7 m) at deep load and a complete double bottom.[21]

Officers were customarily housed aft, but Dreadnought reversed the old arrangement, so that the officers were closer to their action stations. This was very unpopular with the officers, not least because they were now berthed near the noisy auxiliary machinery while the turbines made the rear of the ship much quieter than they had been in earlier steamships. This arrangement lasted among the British dreadnoughts until the King George V class of 1910.[22]

Propulsion

Vickers Sons & Maxim were the prime contractor for the ships machinery but as they had no large turbine experience, they sourced the turbines from Parsons.

Dreadnought was the first battleship to use steam turbines in place of the older reciprocating triple-expansion steam engines. She had two paired sets of Parsons direct-drive turbines, each of which was housed in a separate engine-room and drove two shafts. The high-pressure ahead and astern turbines were coupled to the wing shafts and the low-pressure turbines to the inner shafts. A cruising turbine was also coupled to each inner shaft, although these were not used often and were eventually disconnected.[23] Each of the four main turbines drove an 8-foot-10-inch (2.69 m) diameter three-bladed propeller for 5,750 shaft horsepower (4,290 kW) at 320 rpm.[24]

The turbines were powered by 18 Babcock & Wilcox boilers in three boiler rooms. They had a working pressure of 250 psi (1,724 kPa; 18 kgf/cm2). The turbines were designed to produce a total of 23,000 shp (17,000 kW), but reached nearly 27,018 shp (20,147 kW) during trials in October 1906. Dreadnought was designed for 21 knots (38.9 km/h; 24.2 mph), but reached 21.6 knots (40.0 km/h; 24.9 mph) during trials.[25]

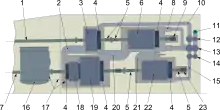

General arrangement of port engine room | 1 – outer shaft; 2 – exhaust trunk from high pressure (HP) for low pressure (LP) astern turbine; 3 – HP astern turbine; 4 – dummy piston; 5 – rotor shaft bearings; 6 – HP ahead turbine; 7 – inner shaft; 8 – main steam to HP ahead turbine; 9 – thrust block (outer); 10 – main steam to HP ahead turbine; 11 – main steam from boiler room; 12 – astern manoueuvring valve; 13 – ahead manoueuvring valve; 14 – cruising manoueuvring valve; 15 – main steam to cruising turbine; 16 – main condenser; 17 – exhaust to condenser; 18 – LP astern turbine; 19 – LP ahead turbine; 20 – exhaust trunk from HP for LP ahead turbine; 21 – exhaust trunk from cruising to HP ahead turbine; 22 – cruising turbine; 23 – thrust block (inner). |

Dreadnought carried 2,868 long tons (2,914 t) of coal, and an additional 1,120 long tons (1,140 t) of fuel oil that was to be sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. At full capacity, she could steam for 6,620 nmi (12,260 km; 7,620 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[26]

Armament

Dreadnought mounted ten 45-calibre BL 12 in (300 mm) Mark X gun in five twin Mark BVIII gun turrets. Three turrets were located along the centreline of the ship, with the forward turret ('A') and two aft turrets ('X' and 'Y'), the latter pair separated by the torpedo control tower located on a short tripod mast. Two wing turrets ('P' and 'Q') were located port and starboard of the forward superstructure respectively.[22]

Dreadnought could deliver a broadside of eight guns between 60° before the beam and 50° abaft the beam. Beyond these limits she could fire six guns aft, and four forward. On bearings 1° ahead or astern she could fire six guns, although she would have inflicted blast damage on the superstructure.[22]

The guns could initially be depressed to −3° and elevated to +13.5°, although the turrets were modified to allow 16° of elevation during the First World War. They fired 850 lb (390 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,725 ft/s (831 m/s); at 13.5°, this provided a maximum range of 16,450 yd (15,040 m)[27] with armour-piercing (AP) 2 crh shells. At 16° elevation, the range was extended to 20,435 yd (18,686 m) using the more aerodynamic, but slightly heavier, 4 crh AP shells. The rate of fire of these guns was one to two rounds per minute.[28] The ships carried 80 rounds per gun.[20]

The secondary armament consisted of twenty-seven 50-calibre, 3 in (76 mm) 12-pounder 18 cwt Mark I guns[Note 2] positioned in the superstructure and on turret tops. The guns had a maximum depression of −10° and a maximum elevation of +20°. They fired 12.5 lb (5.7 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,600 ft/s (790 m/s); this gave a maximum range of 9,300 yd (8,500 m). Their rate of fire was 15 rounds per minute. The ship carried three hundred rounds for each gun.[20]

The original plan was to dismount the eight guns on the forecastle and quarterdeck and stow them on chocks on the deck during daylight to prevent them from being damaged by muzzle blast from the main guns. Gun trials in December 1906 proved that this was more difficult than expected and the two port guns from the forecastle and the outer starboard gun from the quarterdeck were transferred to turret roofs, giving each turret two guns. The remaining forecastle guns and the outer port gun from the quarterdeck were removed by the end of 1907, which reduced the total to twenty-four guns. During her April–May 1915 refit, the two guns from the roof of 'A' turret were reinstalled in the original positions on the starboard side of the quarterdeck. A year later, the two guns at the rear of the superstructure were removed, reducing her to twenty-two guns. Two of the quarterdeck guns were given high-angle mounts for anti-aircraft duties and the two guns abreast the conning tower were removed in 1917.[30]

A pair of QF 6-pounder Hotchkiss AA guns on high-angle mountings were mounted on the quarterdeck in 1915.[30] They had a maximum depression of 8° and a maximum elevation of 60°. The guns fired a 6 lb (2.7 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 1,765 ft/s (538 m/s) at a rate of fire of 20 rounds per minute. They had a maximum ceiling of 10,000 ft (3,000 m), but an effective range of only 1,200 yd (1,100 m).[31] They were replaced by a pair of QF 3-inch 20 cwt guns on high-angle Mark II mounts in 1916. These guns had a maximum depression of 10° and a maximum elevation of 90°. They fired a 12.5 lb (5.7 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s) at a rate of 12–14 rounds per minute. They had a maximum effective ceiling of 23,500 ft (7,200 m).[32]

Dreadnought carried five 18 in (460 mm) submerged torpedo tubes in three compartments. Each compartment had two torpedo tubes, one on each broadside, except for the stern compartment which only had one torpedo tube. The forward torpedo room was forward of 'A' turret's magazine and the rear torpedo room was abaft 'Y' turret's magazine. The stern torpedo compartment was shared with the steering gear. Twenty-three Whitehead Mark III* torpedoes were carried between them. In addition six 14 in (356 mm) torpedoes were carried for her steam picket boats.[22]

Fire control

Dreadnought was one of the first vessels of the Royal Navy to be fitted with instruments for electrically transmitting range, order and deflection information to the turrets. The control positions for the main armament were located in the spotting top at the head of the foremast and on a platform on the roof of the signal tower. Data from a 9 ft (2.7 m) Barr and Stroud FQ-2 rangefinder located at each control position was input into a Dumaresq mechanical computer and electrically transmitted to Vickers range clocks located in the Transmitting Station located beneath each position on the main deck, where it was converted into range and deflection data for use by the guns. Voice pipes were retained for use between the Transmitting Station and the control positions. The target's data was also graphically recorded on a plotting table to assist the gunnery officer in predicting the movement of the target. The turrets, Transmitting Stations, and control positions could be connected in almost any combination.[33]

Firing trials against Hero in 1907 revealed this system's vulnerability to gunfire, as its spotting top was hit twice and a large splinter severed the voice pipe and all wiring running along the mast. To guard against this possibility, Dreadnought's fire-control system was comprehensively upgraded during her refits in 1912–13. The rangefinder in the foretop was given a gyro-stabilized Argo mount and 'A' and 'Y' turrets were upgraded to serve as secondary control positions for any portion or all of the main armament. An additional 9-foot rangefinder was installed on the compass platform. In addition, 'A' turret was fitted with another 9-foot rangefinder at the rear of the turret roof and a Mark I Dreyer Fire Control Table was installed in the main Transmitting Station. It combined the functions of the Dumaresq and the range clock.[34]

Fire-control technology advanced quickly during the years immediately preceding the First World War, and the most important development was the director firing system. This consisted of a fire-control director mounted high in the ship which electrically provided data to the turrets via pointers, which the turret crew were to follow. The director layer fired the guns simultaneously which aided in spotting the shell splashes and minimised the effects of the roll on the dispersion of the shells. A prototype was fitted in Dreadnought in 1909, but it was removed to avoid conflict with her duties as flagship of the Home Fleet.[35] Preparations to install a production director were made during her May–June 1915 refit and every turret received a 9 ft (2.7 m) rangefinder at the same time. The exact date of the installation of the director is not known, other than it was not fitted before the end of 1915, and it was most likely mounted during her April–June 1916 refit.[34]

Armour

Dreadnought used Krupp cemented armour throughout, unless otherwise mentioned. The armour was supplied by William Beardmore's Dalmuir factory.

Her waterline belt measured 11 in (279 mm) thick, but tapered to 7 in (178 mm) at its lower edge. It extended from the rear of 'A' barbette to the centre of 'Y' barbette. Oddly, it was reduced to 9 in (229 mm) abreast 'A' barbette. A 6 in (152 mm) extension ran from 'A' barbette forward to the bow and a similar 4 inch extension ran aft to the stern. An 8 in (203 mm) bulkhead was angled obliquely inwards from the end of the main belt to the side of 'X' barbette to fully enclose the armoured citadel at middle deck level. An 8-inch belt sat above the main belt, but only ran as high as the main deck. One major problem with Dreadnought's armour scheme was that the top of the 11 inch belt was only 2 ft (0.6 m) above the waterline at normal load and it was submerged by over 12 inches at deep load, which meant that the waterline was then protected only by the 8 inch upper belt.[36]

The turret faces and sides were protected by 11 inches of Krupp cemented armour, while the turret roofs used 3 inches of Krupp non-cemented armour (KNC). The exposed faces of the barbettes were 11 inches thick, but the inner faces were 8 inches thick above the main deck. 'X' barbette's was 8 inches thick all around. Below the main deck, the barbettes' armour thinned to four inches except for 'A' barbette (eight inches) and 'Y' which remained 11 inches thick. The thickness of the main deck ranged from 0.75 to 1 in (19 to 25 mm). The middle deck was 1.75 in (44 mm) thick on the flat and 2.75 inches (70 mm) where it sloped down to meet the bottom edge of the main belt. Over the magazine for 'A' and 'Y' turrets it was 3 inches thick, on slope and flat both. The lower deck armour was 1.5 inches (38 mm) forward and 2 inches aft where it increased to 3 inches to protect the steering gear.[34]

The sides of the conning tower were 11 inches thick and it had a 3-inch roof of KNC. It had a communications tube with 8 inch walls of mild steel down to the Transmitting Station on the middle deck. The walls of the signal tower were 8 inches thick while it had a roof of 3 inches of KNC armour. 2 inch torpedo bulkheads were fitted abreast the magazines and shell rooms of 'A', 'X' and 'Y' turrets, but this increased to 4 inches abreast 'P' and 'Q' turrets to compensate for their outboard location.[34]

In common with all major warships of her day, Dreadnought was fitted with anti-torpedo nets, but these were removed early in the war, since they caused considerable loss of speed and were easily defeated by torpedoes fitted with net-cutters.[37]

Electrical equipment

Electrical power was provided by three 100 kW, 100 V DC Siemens generators, powered by two Brotherhood steam and two Mirrlees diesel engines (which later changed to three steam and one diesel).[38] Among the equipment powered by 100 volt DC and 15 volt DC electrical systems were five lifts (elevators), eight coaling winches, pumps, ventilation fans, lighting and telephone systems.[39]

Construction

Dreadnought was the sixth ship of the RN to bear the name.[40] To meet Admiral Fisher's goal of building the ship in a single year, material was stockpiled in advance and a great deal of prefabrication was done from May 1905 onwards with approximately 6,000 man weeks of work expended before she was formally laid down on 2 October 1905 on No.5 Slip.[41] In addition, she was built at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth which was regarded as the fastest-building shipyard in the world. The slip was screened from prying eyes and attempts made to indicate that the design was no different to other battleships.

1,100 men were already employed by the time she was laid down, but soon this number rose to 3,000. Whereas on previous ships the men had worked a 48-hour week, they were required on Dreadnought to work a 69-hour, six day week from 06:00 to 18:00, which included compulsory overtime with only a 30-minute lunch break. While double shifting was considered to ease the long hours which were unpopular with the men, this was not possible due to labour shortages.[41] By Day 6 (7 October), the first of the bulkheads and most of the middle deck beams were in place. By Day 20, the forward part of the bow was in position and the hull plating was well underway. By Day 55 all of the upper deck beams were in place, and by Day 83 the upper deck plates were in position. By Day 125 (4 February), the hull was finished.

Dreadnought was christened with a bottle of Australian wine[42] by King Edward VII on 10 February 1906,[43] after only four months on the ways. The bottle required multiple blows to shatter on a bow that later became famous. Signifying the ship's importance the launch had been planned to be a large elaborate festive event, however as the court was still in mourning for Queen Alexandra's father who had died twelve days before, she did not attend and a more sober event occurred.

Following the launch, fitting out of the ship occurred at No.15 Dock.[44]

Trials

On 1 October 1906, steam was raised and she went to sea on 3 October 1906 for two days of trials at Devonport, only a year and a day after construction started. On the 9th she undertook her eight hour long full power contractor trials off Polperro on the Cornwall coast during which she averaged 20.05 knots and 21.6 knots on the measured mile. She returned to Portsmouth for gun and torpedo trials before she completed her final fitting out. She was commissioned into the fleet on 11 December 1906, fifteen months after she was laid down.[45]

The suggestion[46][47] that her building had been speeded up by using guns and/or turrets originally designed for the Lord Nelson-class battleships which preceded her is not borne out as the guns and turrets were not ordered until July 1905. It seems more likely that Dreadnought's turrets and guns merely received higher priority than those of the earlier ships.[22]

Dreadnought sailed for the Mediterranean Sea for extensive trials in December 1906 calling in at Arosa Bay, Gibraltar and Golfo d'Aranci before crossing the Atlantic to Port of Spain, Trinidad in January 1907, returning to Portsmouth on 23 March 1907. During this cruise, her engines and guns were given a thorough workout by Captain Reginald Bacon, Fisher's former Naval Assistant and a member of the Committee on Designs. His report stated, "No member of the Committee on Designs dared to hope that all the innovations introduced would have turned out as successfully as had been the case."[48] During this time she averaged 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph), slowed only by a damaged rudder, an unprecedented high-speed performance.[49] This shakedown cruise revealed several issues that were dealt with in subsequent refits, notably the replacement of her steering engines and the addition of cooling machinery to reduce the temperature levels in her magazines (cordite degrades more quickly at high temperatures).[50] The most important issue, which was never addressed in her lifetime, was that the placement of her foremast behind the forward funnel put the spotting top right in the plume of hot exhaust gases, much to the detriment of her fighting ability.[51]

Cost

The ship's construction cost £1,785,683, broken down as follows: hull £844,784, propelling and other machinery £319,585, hull fittings, gun mountings, and torpedo tubes £390,145, incidental charges £117,969, guns £113,200.[52] Other sources however state £1,783,883.[53] and £1,672,483.[20]

Service record

From 1907–1911, Dreadnought served as flagship of the Royal Navy's Home Fleet.[54] In 1910, she attracted the attention of notorious hoaxer Horace de Vere Cole, who persuaded the Royal Navy to arrange for a party of Abyssinian royals to be given a tour of a ship. In reality, the "Abyssinian royals" were some of Cole's friends in blackface and disguise, including a young Virginia Woolf and her Bloomsbury Group friends; it became known as the Dreadnought hoax. Cole had picked Dreadnought because she was at that time the most prominent and visible symbol of Britain's naval might.[55]

She was replaced as flagship of the Home Fleet by Neptune in March 1911 and was assigned to the 1st Division of the Home Fleet. She participated in King George V's Coronation Fleet Review in June 1911. Dreadnought became flagship of the 4th Battle Squadron in December 1912 after her transfer from the 1st Battle Squadron, as the 1st Division had been renamed earlier in the year. Between September and December 1913 she was training in the Mediterranean Sea.[56]

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, she was flagship of the 4th Battle Squadron in the North Sea, based at Scapa Flow. She was relieved as flagship on 10 December by Benbow.[57] Ironically for a vessel designed to engage enemy battleships, her only significant action was the ramming and sinking of German submarine SM U-29, skippered by K/Lt Otto Weddigen (of SM U-9 fame), on 18 March 1915. U-29 had broken the surface immediately ahead of Dreadnought after firing a torpedo at Neptune, and Dreadnought cut the submarine in two after a short chase. She almost collided with Temeraire who was also attempting to ram the submarine.[4] Dreadnought thus became the only battleship ever to purposefully sink an enemy submarine.[58][Note 3]

She was refitting at Portsmouth from 18 April-22 June 1916 and missed the Battle of Jutland on 31 May, the most significant fleet engagement of the war. Dreadnought became flagship of the 3rd Battle Squadron on 9 July, based at Sheerness on the Thames, part of a force of pre-dreadnoughts intended to counter the threat of shore bombardment by German battlecruisers. During this time, she fired her AA guns at German aircraft that passed over her headed for London. She returned to the Grand Fleet in March 1918, resuming her role as flagship of the 4th Battle Squadron, but was paid off on 7 August 1918 at Rosyth. She was recommissioned on 25 February 1919 as the tender Hercules to act as a parent ship for the Reserve.[59]

Dreadnought was put up for sale on 31 March 1920 and sold for scrap to Thos W Ward on 9 May 1921 as one of the 113 ships that the firm purchased at a flat rate of £2. 10/- per ton, later reduced to £2. 4/- per ton. As Dreadnought was assessed at 16,650 tons, she cost the shipbreaker £36,630[60] though another source states £44,750.[61] She was broken up at Thos W Ward's new premises at Inverkeithing, Scotland, upon arrival on 2 January 1923.[62] Very few artefacts from Dreadnought survived, although a gun tompion is in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.[63]

Significance

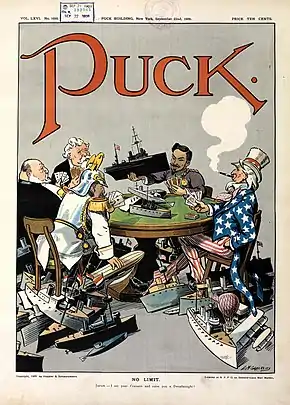

Her design so thoroughly eclipsed earlier types that subsequent battleships of all nations were generically known as "dreadnoughts" and older battleships as "pre-dreadnoughts". Her very short construction time was intended to demonstrate that Britain could build an unassailable lead in the new type of battleships.[64] Her construction sparked off a naval arms race, and soon all major fleets were adding Dreadnought-like ships.[3]

In 1960, Britain's first nuclear submarine was named HMS Dreadnought (S101). The name will be used again for the lead ship of the new class of Trident missile submarines.[65]

The modern acoustic guitar developed with a wide, deep body was named the Dreadnought shape after this ship.[66]

In 2014, a newly classified genus of Titanosaurid sauropod dinosaurs was named Dreadnoughtus due to its gigantic size making it "virtually impervious" to attack, the name means "fears nothing" and was inspired by the battleship.[67]

Notes

- This type of battleship with its secondary armament 9.2 inches or greater would become known retroactively as semi-dreadnoughts. See Sturton, p. 11

- "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 18 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

- The USS New York may have sunk a submarine in October 1918, when she accidentally collided with what was suspected to be a submerged U-boat. That sinking has never been conclusively established, however. See Jones, pp. 66–67

References

- "Dreadnought" in Google Dictionary and Merriam-Webster dictionaries

- Sturton, pp. 76–77

- Gardiner, p. 18

- Burt, p. 38

- Brown, David K, pp. 180–182

- Brown, David K, p. 182

- Parkes, p. 451

- Gardiner and Gray, p. 288

- Brown, David K, p. 188

- Brown, David K, pp. 183–184

- Massie, p. 471

- Massie, p. 470

- Massie, p. 474

- Forczyk, p. 50

- Brown, p. 175

- Brown, David K, pp. 186, 189–90

- Roberts, pp. 12, 25

- Brown, David K, pp. 186, 190

- Brown, Paul; p. 24

- Burt, p. 29

- Roberts, pp. 14, 86–87

- Roberts, p. 28

- Burt, p. 31

- Johnson & Buxton, p. 167

- Roberts, pp. 15–16, 24, 26

- Roberts, p. 25

- Burt, p. 11

- "Britain 12"/45 (30.5 cm) Mark X". navweaps.com. 30 January 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Roberts, p. 30

- "Britain 6-pdr / 8cwt (2.244"/40 (57 mm)) QF Marks I and II". navweaps.com. 16 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- "British 12-pdr (3"/45 (76.2 cm)) 20cwt QF HA Marks I, II, III and IV". navweaps.com. 27 February 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Roberts, pp. 30–31

- Roberts, p. 31

- Brooks, p. 48

- Roberts, pp. 31–32, 139–43

- Archibald, p. 160

- Johnson & Buxton, p. 164

- Brown, Paul; p. 27

- Mizokami, Kyle (26 October 2016). "A Brief History of All the Warships Called "Dreadnought"". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

If the name of Britain's next nuclear sub sounds old, it's because it is very, very old.

- Brown, Paul; p. 25

- "The Battleships – Part 1". ABC TV. 2 July 2002.

- Johnson & Buxton, p. 134

- Johnson & Buxton, p. 153

- Roberts, pp. 13, 16

- Gardiner and Gray, pp. 21–22

- Parkes, p. 479

- Roberts, p. 17

- Burt, pp. 32–33

- Roberts, pp. 34

- Burt, p. 34

- Johnson & Buxton, p. 237

- Parkes, p. 477

- Roberts, pp. 18–20

- "The Dreadnought Hoax". Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- Roberts, pp. 20–21

- Roberts, p. 21

- Sturton, p. 79

- Burt, p. 41

- Johnson & Buxton, p. 306

- Burt, p. 44

- Roberts, pp. 22–23

- "Gun tompion from HMS 'Dreadnought', 1906". Europeana Collections.

- Sturton, p. 11

- "New Successor Submarines Named" (Press release). Gov.uk. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Dreadnought Story". Martin Guitar Company. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- Ewing, Rachel (4 September 2014). "Introducing Dreadnoughtus: A Gigantic, Exceptionally Complete Sauropod Dinosaur - DrexelNow". DrexelNow. Drexel University. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

Sources

- Archibald, E. H. H. (1984). The Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy, AD 897–1984. Poole, Dorset: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1348-8.

- Blyth, Robert J. et al. eds. The Dreadnought and the Edwardian Age (2011)

- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. Naval Policy and History. 32. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40788-5.

- Brown, David K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905 (reprint of the 1997 ed.). London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- Brown, Paul (January 2017), "Building Dreadnought", Ships Monthly: 24–27

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship: Yellow Sea 1904–05. Long Island City, NY: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1992). The Eclipse of the Big Gun: The Warship, 1906–45. Conway's History of the Ship. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-607-8.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Johnston, Ian & Buxton, Ian (2013). The Battleship Builders - Constructing and Arming British Capital Ships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-027-6.

- Jones, Jerry W. (1995). U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I, 1917–1918. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas. OCLC 37111409.

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Massie, Robert K. (1991). Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War. New York and Canada: Random House. ISBN 0-394-52833-6.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Roberts, John (1992). The Battleship Dreadnought. Anatomy of the Ship. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-057-6.

- Ross, Angus. "HMS Dreadnought (1906)—A Naval Revolution Misinterpreted or Mishandled?" The Northern Mariner (April 2010) 20#2 pp: 175–198

- Sturton, Ian, ed. (2008). Conway's Battleships: The Definitive Visual Reference to the World's All-Big-Gun Ships (2nd revised and expanded ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-132-7.

- Sumida, Jon Tetsuro (1993). In Defense of Naval Supremacy: Financial Limitation, Technological Innovation and British Naval Policy, 1889–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08674-4. OCLC 28909592.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Guide to the Dreadnought's distinctive 12-inch (305 mm) guns

- Dreadnought Project's technical material on the weaponry and fire control of the ship

- United States Navy history page on Dreadnought

- History article, with several period photographs

- Illustration of the contemporary naval arms race sparked by Dreadnought

- Maritimequest HMS Dreadnought photo gallery