Ussuri brown bear

The Ussuri brown bear (Ursus arctos lasiotus), also known as the Ezo brown bear and the black grizzly bear,[3] is a subspecies of the brown bear or population of the Eurasian brown bear (Ursus arctos arctos). One of the largest brown bears, a very large Ussuri brown bear may approach the Kodiak bear in size.[4] The Ussuri is not the same subspecies as the grizzly bear.

| Ussuri brown bear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ursidae |

| Genus: | Ursus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | U. a. lasiotus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Ursus arctos lasiotus Gray, 1867[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

baikalensis Ognev, 1924 | |

Appearance

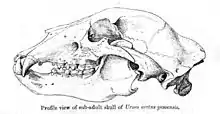

It is very similar to the Kamchatkan brown bear, though it has a more elongated skull, a less elevated forehead, somewhat longer nasal bones and less separated zygomatic arches, and is somewhat darker in color, with some individuals being completely black, a fact which once led to the now refuted speculation that black individuals were hybrids of brown bears and Asian black bears. Adult males have skulls measuring 38.7 cm (15.2 in) long and 23.5 cm (9.3 in) wide. They can occasionally reach greater sizes than their Kamchatkan counterparts: the largest skull measured by Sergej Ognew (1931) was only slightly smaller than that of the largest Kodiak bear (the largest subspecies of brown bears) on record at the time.[4]

Behaviour and biology

On Shiretoko Peninsula, especially in the area called "Banya", many females with cubs often approach fishermen and spend time near people. This unique behavior was firstly noted more than a half century ago, with no casualties or accidents ever recorded. It is speculated that females take cubs and approach fishermen to avoid encountering aggressive adult males.[5]

Dietary habits

Although the diet of an Ussuri brown bear is mainly vegetarian, being the largest predator it is able to kill any prey. In Sikhote Alin, Ussuri brown bears den mostly in burrows excavated into hillsides, though they will on rare occasions den in rock outcroppings or build ground nests. These brown bears rarely encounter Ussuri black bears, as they den at higher elevations and on steeper slopes than the latter species. They may on rare occasions attack their smaller black cousins.[6]

In middle Sakhalin in spring, brown bears feed on the previous year's red bilberry, ants and flotsam, and at the end of the season, they concentrate on the shoots and rhizomes of tall grasses. On the southern part of the island, they feed primarily on flotsam, as well as insects and maple twigs. In springtime in Sikhote Alin, they feed on acorns, Manchurian walnuts and Korean nut pine seeds. In times of scarcity, in addition to bilberries and nuts, they capture larvae, wood-boring ants and lily roots. In early summer, they will strip bark from white-barked fir trees and feed on their cambium and sap. They will also eat berries from honeysuckle, yew, Amur grapevine and buckthorn. In southern Sakhalin, their summer diet consists of currants and chokeberries. In the August period in the middle part of the island, fish comprise 28% of their diet.[4]

In Hokkaido, the brown bear has a diet including small and large mammals, fish, birds and insects such as ants.[7] Recent increases in size and weight, reaching 400 kg (880 lb), or possibly up to 450 kg (990 lb) to 550 kg (1,210 lb),[8] are largely caused by feeding on crops.[9]

Interactions with tigers

.jpg.webp)

Ussuri brown bears are occasionally preyed on by Siberian tigers, and constitute about 1% of their diet (and up to 18.5% together with Asian black bears in very particular cases).[10][11] When preying on bears, tigers regularly target young bears, but adult female Ussuri brown bears are also taken outside their dens.[6][12][13] Siberian tigers most typically attack brown bears in the winter in the bear's hibernaculum.[14] They are typically attacked by tigers more often than the smaller black bears, due to their habit of living in more open areas and their inability to climb trees. When hunting bears, tigers will position themselves from the leeward side of a rock or fallen tree, waiting for the bear to pass by. When the bear passes, the tiger will spring from an overhead position and grab the bear from under the chin with one forepaw and the throat with the other. The immobilised bear is then killed with a bite to the spinal column. After killing a bear, the tiger will concentrate its feeding on the bear's fat deposits, such as the back, legs and groin.[15] Tiger attacks on bears tend to occur when ungulate populations decrease. From 1944 to 1959, more than 32 cases of tigers attacking bears were recorded in the Russian Far East. In the same period, four cases of brown bears killing female and young tigers were reported, both in disputes over prey and in self-defense.[15][16][17][18] Gepnter et al. (1972) stated bears are generally afraid of tigers and change their path after coming across tiger trails. In the winters of 1970–1973, Yudakov and Nikolaev recorded 1 case of brown bear showing no fear of the tigers and another case of brown bear changing path upon crossing tiger tracks.[10][15][19][20] Large brown bears may actually benefit from the tiger's presence by appropriating tiger kills that the bears may not be able to successfully hunt themselves and follow.[21] During telemetry research in the Sikhote-Alin protected area, 44 direct confrontations between the two predators were observed, in which bears were killed in 22 cases, and tigers in 12 cases.[22]

Range and status

The brown bear is found in the Ussuri krai, Sakhalin, the Amur Oblast, northward to the Shantar Islands, Iturup Island, northeastern China, the Korean peninsula, Hokkaidō and Kunashiri Island. Until the 13th century, bears inhabited the islands of Rebun and Rishiri, having crossed the La Pérouse Strait[23] to reach them. They were also present on Honshu during the last glacial period, but were possibly driven to extinction either by competing with Asian black bears[24] or by habitat loss due to climate change. There are three genetic groups, distinct for at least 3 million years which reached to Hokkaido via Honshu at different times.[25][26]

About 500–1,500 Ussuri brown bears are present in Heilongjiang, and are classed as a vulnerable species. Illegal hunting and capture has become a very serious contributing factor to the decline in bear numbers, as their body parts are of high economic value.[27]

Five regional sub-populations of Ussuri brown bears are now recognized in Hokkaido. Of these, the small size and isolation of the western Ishikari subpopulation has warranted its listing as an endangered species in Japan’s Red Data Book. 90 to 152 brown bears are thought to dwell in the West Ishikari Region and from 84 to 135 in the Teshio-Mashike mountains. Their habitat has been severely limited by human activities, especially forestry practices and road construction. Excessive harvesting is also a major factor in limiting their population.[27] In 2015, the Biodiversity Division of the Hokkaido government estimated the population as being as high as 10,600.[28]

In Russia, the Ussuri brown bear is considered a game animal, though it is not as extensively hunted as the Eurasian brown bear.[27]

In Korea, a few of these bears still exist only in the North, where this bear is officially recognized as natural monument by its government. Traditionally called Ku'n Gom (Big Bear), whereas black bears are called Gom (bear), the Ussuri brown bear became extinct many years ago in South Korea largely due to poaching. In North Korea, there are two major areas of brown bear population: including Ja Gang Province and Ham Kyo'ng Mountains. The ones from JaGang province are called RyongLim Ku'n Gom (RyongLim big bear) and they are listed as Natural Monument No.124 of North Korea.[29] The others from Hamkyo'ng Mountains are called GwanMoBong Ku'n Gom (GwanMo Peak big bear) and they are listed as Natural Monument No.330 of North Korea.[30] All big bears (Ussuri brown bears) in North Korea are mostly found around the peak areas of mountains. Their average size varies from 150 kg to 250 kg for Ryonglim bears found in the area south of Injeba'k Mountain, up to average of 500 kg to 600 kg for the ones found in the area north of Injeba'k Mountain.[29] As of May 2020, the Ussuri brown bear was reclassified as "Least Concern".

Attacks on humans

In Hokkaido, during the first 57 years of the 20th century, 141 people died from bear attacks, and another 300 were injured.[31] The Sankebetsu brown bear incident (三毛別羆事件, Sankebetsu Higuma jiken), which occurred in December 1915 at Sankei in the Sankebetsu district was the worst bear attack in Japanese history, and resulted in the deaths of seven people and the injuring of three others.[32] The perpetrator was a 380 kg and 2.7 m tall brown bear, which twice attacked the village of Tomamae, returning to the area the night after its first attack during the prefuneral vigil for the earlier victims. The incident is frequently referred to in modern Japanese bear incidents, and is believed to be responsible for the Japanese perception of bears as man-eaters.[31]

From 1962 to 2008 there were 86 attacks and 33 deaths from bears in Hokkaido.[33]

Cultural associations

.jpg.webp)

The Ainu people worship the Ussuri brown bear, eating its flesh and drinking its blood as part of a religious festival known as Iomante.

References

- McLellan, B.N.; Proctor, M.F.; Huber, D. & Michel, S. (2017). "Ursus arctos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, J. E. (1867). "Note on Ursus lasiotus, a hairy-eared bear from North China". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Ser. 3. 20 (118): 301. doi:10.1080/00222936708694139.

- Storer, T.I.; Tevis, L.P. (1996). California Grizzly. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 335, 42–187. ISBN 978-0-520-20520-8. Alt URL

- V. G. Heptner; N. P. Naumov, eds. (1998). Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 1a, Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears)]. II, Part 1a. Washington, D.C., USA: Science Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-886106-81-9.

- "288回「知床ヒグマ親子 番屋に大集合!」│ダーウィンが来た!生きもの新伝説".

- Seryodkin, I.V. (2003). "Denning ecology of brown bears and Asiatic black bears in the Russian Far East" (PDF). Ursus. 14 (2): 153–161. JSTOR 3873015.

- Onoyama, Keiichi (1987-11-16). "Ants as prey of the Yezo brown bear Ursus arctos yesoensis with consideration on its feeding habits" (PDF). Res. Bull. Obihiro University. Obihiro, Hokkaidō, Japan: Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine. 15: 313–318. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- "ヒグマ・ベーリングヒグマ".

- 日本テレビ. "体重400キロのヒグマ捕獲 なぜ巨大化?|日テレNEWS24".

- Seryodkin; et al. (2005). "Relationship between tigers, brown bears, and Himalayan black bears". Tigers of Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik: Ecology and Conservation: 156–163.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Tiger". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 95–202.

- Frasef, A. (2012). Feline Behaviour and Welfare. CABI. pp. 72–77. ISBN 978-1-84593-926-7.

- Prynn, David (2004). Amur tiger. Russian Nature Press. p. 115.

- V.G. Heptner and N.P. Naumov. Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol 2 IIa 1998. New Delhi, India: Amerind Publishing. p671

- Geptner, V.G & Sludskii, A.A. Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2. pp. 175–177. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- Mammals of the Soviet Union Volume 2, by V.G Heptner & A.A. Sludskii, p177

- Seryodkin, I. V., J. M. Goodrich, A. V. Kostyrya, B. O. Schleyer, E. N. Smirnov, L. L. Kerley, and D. G. Miquelle (2005). "Relationship between tigers, brown bears, and Himalayan black bears". pp. 95-202 in D. G. Miquelle, E. N. Smirnov, and J. M. Goodrich (eds.), Tigers of Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik: Ecology and Conservation. Vladivostok, Russia: PSP.

- Table 1. Location, physical status, size and circumstances of deaths of Amur tiger males in the Russian Far East, 1970-1994.

- Yudakov, A. G. & Nikolaev, I. G. (2004). "Hunting Behavior and Success of the Tigers' Hunts". The Ecology of the Amur Tiger based on Long-Term Winter Observations in 1970-1973 in the Western Sector of the Central Sikhote-Alin Mountains (english translation ed.). Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far-Eastern Scientific Center, Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

- Yudakov, A. G.; Nikolaev, I. G. (2004). "Hunting Behavior and Success of the Tigers' Hunts". The Ecology of the Amur Tiger based on Long-Term Winter Observations in 1970–1973 in the Western Sector of the Central Sikhote-Alin Mountains (english translation ed.). Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far-Eastern Scientific Center, Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

- Miquelle, D.G.; Smirnov, E.N.; Goodrich, J.M. (2005). "1". Tigers of Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik: ecology and conservation. Vladivostok, Russia: PSP.

- Seryodkin, I. V.; Goodrich, J. M.; Kostyria, A. V.; Smirnov, E. N.; Miquelle, D. G. (2011). "Intraspecific relationships between brown bears, Asiatic black bears and the Amur tiger". 20th International Conference on Bear Research & Management (PDF). International Association for Bear Research and Management. p. 64.

- 『野生動物調査痕跡学図鑑』 p.356

- 坪田敏男, 山崎晃司, 2011, 日本のクマ: ヒグマとツキノワグマの生物学, University of Tokyo Press

- Mano T., ヒグマ研究におけるユーラシア東部の重要性とサケとクマがつなぐ海と森, 5.ヒグマ:海と陸との生態系のつながり、極東ロシアと北海道のヒグマ, pp.99-112

- Mano T., Masuda R., Tsuruga H., ヒグマをとおしてみた北海道・極東・ユーラシア

- Chapter 7. Brown Bear Conservation Action Plan for Asia. pp. 123-143 in Bears. Christopher Servheen, Stephen Herrero, Bernard Peyton (eds.). IUCN (1999). ISBN 2831704626

- Higuma Population Estimates pref.hokkaido.lg.jp (2 December 2015)

- North Korean Human Geography, Ryonglim Big Bear. cybernk.net

- North Korean Human Geography, Gwanmobong Big Bear. cybernk.net

- Knight, John (2000). Natural Enemies: People-Wildlife conflicts in Anthropological Perspective. p. 254. ISBN 0-415-22441-1.

- "Fu Watto Tomamae". Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- Chavez, Amy The lowdown on Hokkaido bears March 15, 2008 Japan Times Retrieved September 8, 2016

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ursus arctos lasiotus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Ursus arctos lasiotus. |