United States Life-Saving Service

The United States Life-Saving Service[1] was a United States government agency that grew out of private and local humanitarian efforts to save the lives of shipwrecked mariners and passengers. It began in 1848 and ultimately merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the United States Coast Guard in 1915.

Seal | |

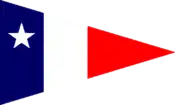

Pennant | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1878 |

| Dissolved | 1915 merged with (United States Revenue Cutter Service) |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

| Agency executive |

|

Early years

The concept of assistance to shipwrecked mariners from shore-based stations began with volunteer lifesaving services, spearheaded by the Massachusetts Humane Society. It was recognized that only small boats stood a chance of assisting those close to the beach. A sailing ship trying to help near to the shore stood a good chance of also running aground, especially if there were heavy onshore winds. The Massachusetts Humane Society founded the first lifeboat station at Cohasset, Massachusetts. The stations were small shed-like structures, holding rescue equipment that was to be used by volunteers in case of a wreck. The stations, however, were only near the approaches to busy ports and, thus, large gaps of coastline remained without lifesaving equipment.[2]

Formal federal government involvement in the lifesaving business began on August 14, 1848 with the signing of the Newell Act, which was named for its chief advocate, New Jersey Representative William A. Newell. Under this act, the United States Congress appropriated $10,000 to establish unmanned lifesaving stations along the New Jersey coast south of New York Harbor and to provide "surf boat, rockets, carronades and other necessary apparatus for the better preservation of life and property from shipwreck on the coast of New Jersey".[3] That same year the Massachusetts Humane Society also received funds from Congress for lifesaving stations on the Massachusetts coastline. Between 1848 and 1854 other stations were built and loosely managed.[2] The stations were administered by the United States Revenue Marine (later renamed the United States Revenue Cutter Service). They were run with volunteer crews, much like a volunteer fire department.[2]

In September 1854, a Category 4 hurricane, the Great Carolina Hurricane of 1854, swept through the East Coast of the United States, causing the deaths of many sailors. This storm highlighted the poor condition of the equipment in the lifesaving stations, the poor training of the crews and the need for more stations. Additional funds were appropriated by Congress, including funds to employ a full-time keeper at each station and two superintendents.[2]

Still not officially recognized as a service, the system of stations languished until 1871 when Sumner Increase Kimball was appointed chief of the Treasury Department's Revenue Marine Division. One of his first acts was to send Captain John Faunce of the Revenue Marine Service on an inspection tour of the lifesaving stations. Captain Faunce's report noted that "apparatus was rusty for want of care and some of it ruined."[2]

Kimball convinced Congress to appropriate $200,000 to operate the stations and to allow the Secretary of the Treasury to employ full-time crews for the stations. Kimball instituted six-man boat crews at all stations, built new stations, and drew up regulations with standards of performance for crew members.[2]

By 1874, stations were added along the coast of Maine, Cape Cod, the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and Port Aransas, Texas. The next year, more stations were added to serve the Great Lakes and the Houses of Refuge in Florida. In 1878, the network of lifesaving stations were formally organized as a separate agency of the United States Department of the Treasury, called the Life-Saving Service.[2]

Formal structure

The stations of the Service fell into three categories: lifesaving, lifeboat, and houses of refuge. Lifesaving stations were manned by full-time crews during the period when wrecks were most likely. On the East Coast, this was usually from April to November, and was called the "active season." By 1900, the active season was year-round. Most stations were in isolated areas and crewmen had to perform open beach launchings. That is, they were required to launch their boats from the beach into the surf.[4] The Regulations of Life-Saving Service of 1899, Article VI, "Actions at Wrecks," Section 252, remained in force after creation of the Coast Guard in 1915, and Section 252 was copied word for word into the new Instructions for United States Coast Guard Stations, 1934 edition.[5] That section gave rise to the rescue crew's unofficial motto, "You have to go out, but you don't have to come back."[5]

Before 1900, there were very few recreational boaters and most assistance cases came from ships engaged in commerce.[4] Nearly all lifeboat stations were located at or near port cities. Here, deep water, combined with piers and other waterfront structures, allowed launching heavy lifeboats directly into the water by marine railways on inclined ramps. In general, lifeboat stations were on the Great Lakes, but some lifesaving stations were in the more isolated areas of the lakes. The active season on the Great Lakes stretched from April to December. An exception was the nation's first rescue center on the inland waterways, the United States Life Saving Station #10, established in 1881 at the Falls of the Ohio at Louisville, Kentucky, on the Ohio River.[4]

Houses of refuge made up the third category of Life Saving Service units. These stations were on the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. A paid keeper and a small boat were assigned to each house, but the organization did not include active manning and rescue attempts. It was felt that along this stretch of coastline, shipwrecked sailors would not die of exposure to the cold in the winter as in the north. Therefore, only shelters would be needed.[4]

Merger to create Coast Guard

On January 28, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson signed the "Act to Create the Coast Guard," merging the Life-Saving Service with the Revenue Cutter Service to create the United States Coast Guard.[2] By the time the act was signed there was a network of more than 270 stations covering the Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico Coasts, and the Great Lakes.

See also

References

- This article contains information created by the United States Coast Guard and is in the public domain.

- Despite the lack of hyphen in its insignia, the agency itself is hyphenated in government documents including: Treasury Department, United States Life-Saving Service (1876). Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30 1876. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office – via University of Michigan. and An Act To create the Coast Guard by combining therein the existing Life-Saving Service and Revenue-Cutter Service (PDF). Sixty-Third Congress, Session III, CHS. 19, 20. 1915. January 25, 1915.

- United States Coast Guard (USCG) (2011). "U.S. Lifesaving Service History". USCG. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Newell Act (9 Stat. 322), enacted August 14, 1848

- Noble, Dennis L. (1976). "A Legacy: The United States Life-Saving Service" (PDF). United States Coast. p. 9. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- "Coast Guard History". United States Coast Guard. December 21, 2016.

Further reading

- O'Connor, W. D. The United States Life Saving Service, The Popular science monthly, volume 15, May-Oct 1879 pp. 182–196.

- Noble, Dennis L., That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915 (Naval Institute Press, 1994). ISBN 1-55750-627-2.

- Mobley, Joe A., "Ship Ashore! The U.S. Lifesavers of Coastal North Carolina" (Division of Archives and History, N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1994).

- Wreck & Rescue: The Journal of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association, 1996- .

- Carbone, Elisa L., "Storm Warriors" (Random House Children's Books, 2002). Children's fiction.

- Stonehouse, Frederick, "Wreck Ashore: The United States Life-Saving Service on the Great Lakes" (Lake Superior Port Cities, 2003). ISBN 0-942235-22-3.

- James W. Claflin: Lighthouses and Life Saving Along Cape Cod. Arcadia Publishin 2014, ISBN 978-1-4671-2213-9.

External links

- Annual report of the US Life Saving Service 1876 - 1914 (hosted at Hathitrust)

- Little Kinnakeet Lifesaving Station: Home to Unsung Heroes, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- The U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association

- The U.S. Coast Guard's Assignment to the Department of Homeland Security

- Lifesaving on the Cape Cod Coast

- Life-Saving Stations to Visit

- A Legacy: The United States Life-Saving Service

- U.S. Coast Guard history.

- Life Saving Service along Lake Superior

- U.S.L.S.S. Living History Association