Great Mississippi Flood of 1927

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States, with 27,000 square miles (70,000 km2) inundated in depths of up to 30 feet (9 m). The uninflated cost of the damage has been estimated to be between 246 million and 1 billion dollars.[1]

Mississippi River Flood of 1927 showing flooded areas and relief operations. | |

| Date | 1926–1929 |

|---|---|

| Location | Particularly Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi along with Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Texas |

| Deaths | about 500 |

Ninety-four percent of more than 630,000 people affected by the flood lived in the states of Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana, most in the Mississippi Delta. More than 200,000 African Americans were displaced from their homes along the Lower Mississippi River and had to live for lengthy periods in relief camps. As a result of this disruption, many joined the Great Migration from the south to northern and midwestern industrial cities rather than return to rural agricultural labor.

To prevent future floods, the federal government built the world's longest system of levees and floodways. Then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover's handling of the crisis improved his reputation, helping him become president in 1928. Political turmoil from the disaster at the state level aided the gubernatorial election of Huey Long in Louisiana.

Events

The flood began with extremely heavy rains in the central basin of the Mississippi in the summer of 1926. By September, the Mississippi's tributaries in Kansas and Iowa were swollen to capacity. On Christmas Day of 1926,[2] the Cumberland River at Nashville, Tennessee, exceeded 56 ft 2 in (17.1 m), a level that remains a record to this day.

Flooding peaked in the Lower Mississippi River near Mound Landing, Mississippi, and Arkansas City, Arkansas, and broke levees along the river in at least 145 places.[3] The water flooded more than 27,000 square miles (70,000 km2) of land, and left more than 700,000 people homeless. Approximately 500 people died as a result of flooding.[4] Monetary damages due to flooding reached approximately $1 billion, which was one-third of the federal budget in 1927. If the event were to have occurred in 2007, the damages would total around $930 billion or $1 trillion (measured in 2007 U.S. dollars).[5]

The flood affected Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas. Arkansas was hardest hit, with 14% of its territory covered by floodwaters extending from the Mississippi and Arkansas deltas. By May 1927, the Mississippi River below Memphis, Tennessee, reached a width of 80 miles (130 km).[6] Without trees, grasses, deep roots, and wetlands, the denuded soil of the watershed could not do its ancient work of absorbing floodwater after seasons of intense snow and rain.[7]

Attempts at relief

On April 15, Good Friday, 1927, 15 inches (380 mm) of rain fell in New Orleans in 18 hours.[8] More than 4 feet (1.2 m) of water covered parts of the city. A group of influential bankers in town met to discuss how to guarantee the safety of the city, as they had already learned of the massive scale of flooding upriver.[8] A few weeks after, they arranged to set off about 30 tons of dynamite on the levee at Caernarvon, Louisiana, releasing 250,000 cu ft/s (7,000 m3/s) of water. This was intended to prevent New Orleans from suffering serious damage, and it resulted in flooding much of the less densely populated St. Bernard Parish and all of Plaquemines Parish's east bank. As it turned out, the destruction of the Caernarvon levee was unnecessary; several major levee breaks well upstream of New Orleans, including one the day after the demolitions, released major amounts of flood waters, reducing the water that reached the city. The New Orleans businessmen did not compensate the losses of people in the downriver parishes.[9]

To address the disaster Congress passed the Mississippi Flood Control Act, which put greater stress on construction in the Mississippi Delta Levee Camps despite warnings from the NAACP about harsh living conditions and mistreatment of black laborers within the camps.

Abatement and assessment

By August 1927, the flood subsided. Hundreds of thousands of people had been made homeless and displaced; properties, livestock and crops were destroyed.

In terms of population affected, in territory flooded, in property loss and crop destruction, the flood's figures were "staggering". Great loss of life was averted by relief efforts, largely by the American Red Cross through the efforts of local workers. [10]

African Americans, comprising 75% of the population in the Delta lowlands and supplying 95% of the agricultural labor force, were most affected by the flood. Historians estimate that of the 637,000 people forced to relocate by the flooding, 94% lived in three states: Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana; and that 69% of the 325,146 who occupied the relief camps were African American.[11] In one location, over 13,000 evacuees near Greenville, Mississippi, were gathered from area farms, and evacuated to the crest of the unbroken Greenville Levee. But many were stranded there for days without food or clean water.

Political and social responses

Following the Great Flood of 1927, the US Army Corps of Engineers was charged with taming the Mississippi River. Under the Flood Control Act of 1928, the world's longest system of levees was built. Floodways that diverted excessive flow from the Mississippi River were constructed.[12] While the levees prevented some flooding, scientists have found that they changed the flow of the Mississippi River, with the unintended consequence of increasing flooding in succeeding decades. Channeling of waters has reduced the absorption of seasonal rains by the floodplains, increasing the speed of the current and preventing the deposit of new soils along the way.

States also needed money to rebuild their roads and bridges. Louisiana received $1,067,336 from the federal government for rebuilding,[13] but it had to institute a state gasoline tax to create a $30,000,000 fund to pay for new hard-surfaced highways.[14]

The devastation of the flood and the strained racial relations resulted in many African Americans joining the Great Migration from affected areas to northern and midwestern cities, a movement that had been underway since World War I. The flood waters began to recede in June 1927, but interracial relations continued to be strained. Hostilities had erupted between the races; a black man was shot and killed by a white police officer when he refused to be forced at gunpoint to unload a relief boat.[15][16] As a result of displacements lasting up to six months, tens of thousands of local African Americans moved to the big cities of the North, particularly Chicago; many thousands more followed in the following decades.[17][18]

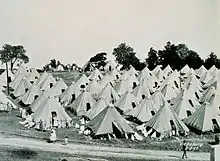

Herbert Hoover enhanced his reputation by his achievements in directing flood relief operations as Secretary of Commerce under President Calvin Coolidge. The next year Hoover easily won the Republican 1928 nomination for President, and the general election that year. In upstate Louisiana, anger among yeomen farmers directed at the New Orleans elite for its damage of downriver parishes aided Huey Long's election to the governorship in 1928.[19]:408–409, 477, 487 Hoover was much lauded initially for his masterful handling of the refugee camps known as "tent cities".[20] These densely populated camps required basic necessities which were difficult to attain, such as water and sanitation facilities. Hoover used a combination of bureaucratic resources and grassroots forces to give the tent cities the opportunity to become self-sufficient. This method presented difficulties, as rural leaders were unprepared to manage the chaotic circumstances found in large camps. This led Hoover eventually to place the relief camps under government supervision.[20]

The refugee camps also dealt with extreme racial inequality, as supplies and means of evacuation after flooding were given strictly to white citizens, with Blacks receiving only leftovers. African Americans also did not receive supplies without providing the name of their white employer or voucher from a white person. In order to fully exploit black labor, Blacks were frequently forced to work against their will, and were not permitted to leave the camps.[21] Later reports about the poor treatment in camps led Hoover to make promises of change to the African-American community, which he broke. As a result, he lost the Black vote in the North in his re-election campaign in 1932.[19]:259–290 [note 1] Several reports on the terrible situation in the refugee camps, including one by the Colored Advisory Commission headed by Robert Russa Moton, were kept out of the media at Hoover's request, with the pledge of further reforms for Blacks after the presidential election in 1928. His failure to deliver followed other disappointments by the Republican Party; Moton and other influential African Americans began to encourage Black Americans to align instead with the national Democrats.[19]:415

Representation in other media

A feature-length documentary, The Great Flood (2014) was made incorporating archival footage from news coverage of the flood.[22][23] The flood is referred to as the "High Water of 1927" in the movie The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman.

Several musicians reflected the 1927 flood in their music:

- "Mississippi Heavy Water Blues", by Barbecue Bob (1927)[24]

- "Backwater Blues" by Bessie Smith (1927)

- "When the Levee Breaks", by Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy (1929) (covered by Led Zeppelin in 1971)

- "High Water Everywhere", by Charley Patton (1929) (referred to in "High Water (For Charley Patton)" by Bob Dylan in 2001)

- "Tupelo Blues" by John Lee Hooker (1959)

- "Tupelo" by Albert King, Pops Staples, & Steve Cropper (1969) (covered by Nick Cave in 1985)

- "Down in the Flood" by Bob Dylan (1967)

- "Louisiana 1927" by Randy Newman (1974)

- "Mississippi" by Bob Dylan (2001)

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- In the South, African Americans were still overwhelmingly disenfranchised by state constitutions and practices, as they remained until after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

References

- Watkins, T.H. (April 13, 1997). "Boiling Over". The New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Evans, David (2007). "Bessie Smith's 'Back-Water Blues': The story behind the song". Popular Music. 26: 97. doi:10.1017/S0261143007001158.

- Spencer, Robyn (1 January 1994). "Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor". The Journal of Negro History. 79 (2): 170–181. doi:10.2307/2717627. JSTOR 2717627.

- "Man vs. Nature: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927". News.nationalgeographic.com. 2001-05-01. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- Smith, James A.; Baeck, Mary Lynn (2015). ""Prophetic vision, vivid imagination": The 1927 Mississippi River flood". Water Resources Research. 51 (12): 9964. Bibcode:2015WRR....51.9964S. doi:10.1002/2015WR017927. OSTI 1565405.

- "Science Question of the Week – natural disasters, floods – April 05, 2002". Archived from the original on August 29, 2009.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 Laid Bare the Divide Between the North and the South". Smithsonian. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- "American Experience | New Orleans | People & Events". PBS. 1927-04-15. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- Barry, John M. (2007-09-17). Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416563327.

- "Black Oppression and the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927". www.icl-fi.org. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- "The Final Report of the Colored Advisory Commission Appointed to Cooperate with The American National Red Cross and the President's Committee on Relief Work in the Mississippi Valley Flood Disaster of 1927". PBS. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- "After the Flood of 1927". Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- "CONTENTdm". Cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "CONTENTdm". Cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- William Alexander Percy (2006) [1941]. Lanterns on the Levee: Recollections of a Planter's Son. Reprint. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 257–258, 266. ISBN 978-0-8071-0072-1.

- "One Man's Experience". PBS. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

The police were sent into the Negro section to comb from the idlers the required number of workers. Within two hours, the worst had happened: a Negro refused to come with the officer, and the officer killed him.

- "Voices from the Flood". PBS. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

After the flood, the Delta would never be the same. With their meager crops destroyed, and feeling deeply mistrustful of white Delta landlords after their poor treatment as refugees, thousands of African Americans left the area. Many headed north to seek their fortunes in Chicago.

- Hornbeck, Richard; Naidu, Suresh (2014). "When the Levee Breaks: Black Migration and Economic Development in the American South†". American Economic Review. 104 (3): 963–990. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.364.6672. doi:10.1257/aer.104.3.963. ISSN 0002-8282.

- Barry, John M. (1998-04-02). Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. ISBN 978-0-684-84002-4.

- Lohof, Bruce A. (1970). "Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Mississippi Flood of 1927". American Quarterly. 22 (3): 690–700. doi:10.2307/2711620. ISSN 0003-0678. JSTOR 2711620.

- Rivera, Jason David; Miller, DeMond Shondell (2007). "Continually Neglected: Situating Natural Disasters in the African American Experience". Journal of Black Studies. 37 (4): 502–522. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.582.2079. doi:10.1177/0021934706296190. JSTOR 40034320.

- "The Great Flood". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "The Great Flood". IMDb. 8 January 2014.

- Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-85868-255-6.

Further reading

- Barry, John M. (1997). Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84002-4.

- Daniel, Pete (1977). Deep'n as It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-02122-6.

- Eldredge, Charles C. (2007). John Steuart Curry's Hoover and the Flood: Painting Modern History. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3087-1.

- Faulkner, William (1927). "Old Man" published in The Wild Palms (1939) Random House, New York

- Parrish, Susan (2017). The Flood Year 1927: A Cultural History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16883-8.

- Payne, John Barton (1929). The Mississippi Valley Flood Disaster of 1927. Official Report of the Relief Operations. Washington, DC: American National Red Cross. OCLC 1610750.

- RMS Special Report (2007). The 1927 Great Mississippi Flood: 80-Year Retrospective (PDF). San Francisco: Risk Management Solutions. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2014-12-06.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Sevier, Richard P. (2003). Madison Parish (Images of America). Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-1510-6. Contains over 200 pictures of the flood as it affected the Tensas Basin in eastern Louisiana. Website with selected photographs from the book.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. |

- A film clip of the Mississippi River Flood of 1927 is available at the Internet Archive – Short silent film of the flood aftermath and relief efforts for the refugees. Produced by the US Army Signal Corps.

- Disaster Response and Appointment of a Recovery Czar: The Executive Branch's Response to the Flood of 1927, well-referenced CRS report.

- 1927 Flood Photograph Collection, Historic images of the flood from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

- Delta Geography, Information about how the Flood of 1927 influences the life of people who live in the Delta in the 21st century

- Fatal Flood, PBS American Experience

- The Final Report of the Colored Advisory Commission, Text of the report provided by PBS: "The American Experience"

- U.S. Army Engineers periodical ESPRIT, March 2002 – Lead article relying heavily on John M. Barry's book; includes some photographs.

- Youtube Video of 1927 Mississippi Flood, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Vicksburg District