The Unconquered (1940 play)

The Unconquered is a three-act play written by Russian-American author Ayn Rand as an adaptation of her 1936 novel We the Living. The story follows Kira Argounova, a young woman living in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. Her lover Leo Kovalensky develops tuberculosis. To get money for his treatment, Kira has an affair with a Communist official, Andrei Taganov. After recovering from his illness, Leo becomes involved with black market food sales that Andrei is investigating. When Andrei realizes that Kira loves Leo, he helps his rival avoid prosecution, then commits suicide. Leo leaves Kira, who decides to risk her life escaping the country.

| The Unconquered | |

|---|---|

| |

| Written by | Ayn Rand |

| Based on | We the Living by Ayn Rand |

| Date premiered | February 13, 1940 |

| Place premiered | Biltmore Theatre |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Melodrama |

| Setting | Petrograd, Russia[lower-alpha 1] |

Rand sold an option for the adaptation to producer Jerome Mayer and wrote a script, but he was unable to stage the play. Upon learning about the script, Russian actress Eugenie Leontovich recommended it to producer George Abbott. He staged the play on Broadway in February 1940. The production was troubled by problems with the script and the cast, including the firing of Leontovich and other actors before the premiere. When the play opened at the Biltmore Theatre, it was a critical and financial failure, and closed in less than a week. It was the last of Rand's plays produced during her lifetime. The script was published in 2014.

History

Ayn Rand was born in 1905 in Saint Petersburg, then capital of the Russian Empire, to a bourgeois family whose property was expropriated by the Bolshevik government after the 1917 Russian Revolution.[3] Concerned about her safety due to her strong anti-Communist views, Rand's family helped her emigrate to the United States in 1926.[4] She moved to Hollywood, where she obtained a job as a junior screenwriter and also worked on other writing projects.[5] Her play Night of January 16th opened on Broadway in September 1935 and ran until early April 1936. Later that month, her debut novel, We the Living, was published by Macmillan.[6] She drew on her experiences to depict life in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, and expressed her criticisms of the Soviet government and Communist ideology.[7]

Shortly after We the Living was published, Rand began negotiations with Broadway producer Jerome Mayer to do a theatrical adaptation.[8] They reached an agreement by July 1936. By January 1937, Rand had completed a script, but Mayer had difficulty casting the production because of the story's anti-Communist content.[9] Without a recognized star in the cast, Mayer's financing fell through.[10]

.jpg.webp)

In 1939, Russian-born actress Eugenie Leontovich, who had read We the Living and heard that an adaptation had been written, approached Rand. Like Rand, Leontovich came from a family that suffered after the revolution; the Bolsheviks tortured and killed her three brothers, who served in the anti-Communist White Army.[11] Leontovich asked for a copy of the script, which she sent to her friend George Abbott, a successful Broadway producer.[12][13] Abbott decided to produce and direct the adaptation; he hired scenic designer Boris Aronson, who was also a Russian immigrant, to create the sets.[14] Rand hoped the theatrical adaptation of her novel would create interest among Hollywood producers in doing a film version. This hope was bolstered when Warner Bros. studio invested in the stage production,[13] which was retitled The Unconquered.[15]

Rand had a bad experience with the Broadway production of Night of January 16th because of script changes mandated by the producer, so she insisted on having final approval of any revisions to The Unconquered.[16][17] The production was quickly troubled as Abbott requested many changes that Rand refused. To facilitate rewrites, Abbott asked experienced playwright S. N. Behrman to work with Rand as a script doctor.[17][18] Abbott also decided to replace actor John Davis Lodge, who was hired to play Andrei.[16]

Although she was much older,[lower-alpha 2] Leontovich planned to star as college-aged Kira.[12][13] Abbott and Rand developed concerns about Leontovich's approach to the role during rehearsals. Rand later described Leontovich's performance as "ham all over the place", which Rand attributed to Leontovich's background with the Moscow Art Theatre.[20] A preview production opened in Baltimore on December 25, 1939, with Leontovich playing Kira alongside Onslow Stevens as Leo and Dean Jagger as Andrei.[21] Rand's husband, Frank O'Connor, was cast in a minor role as a GPU officer.[16] The opening night was complicated by a last-minute accident when Howard Freeman, who was playing Morozov, fell from the theatre's upper tier and fractured his pelvis. No replacement was ready, so his part was read from the script rather than performed.[22][lower-alpha 3] The Baltimore production closed on December 30.[23]

.jpg.webp)

After negative reviews for the preview, Abbott cancelled a Broadway debut planned for January 3, 1940, so he could recast and Rand could make script changes.[23] Rand and Abbott agreed to fire Leontovich. Rand delivered the news so that Abbott did not have to confront his longtime friend.[24] Abbott made several other cast changes, including replacing Stevens with John Emery and replacing Doro Merande with Ellen Hall as Bitiuk.[23]

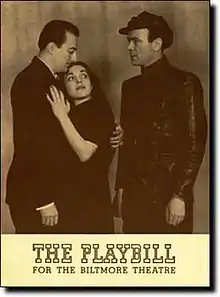

For the Broadway production, Helen Craig took the lead role as Kira.[16] Rand made the updates to the script that Abbott requested, but she had lost confidence in the production. She did not usually drink, but got drunk before the dress rehearsal to "cut off any emotional reaction" to the "disaster".[25] A final preview performance was staged on February 12, 1940, as a benefit for the Home for Hebrew Infants, a New York orphanage.[26] The play opened on Broadway the next day at the Biltmore Theatre, but closed after five days following scathing reviews and just six performances.[27][28]

For more than 70 years after its production, the play was unpublished and available only as a typescript stored at the New York Public Library.[29] In 2014, Palgrave Macmillan published a volume with both the final script and an earlier version, edited by Robert Mayhew.[30]

Plot

In the Russian winter of 1924, Leo Kovalensky returns to his apartment in Petrograd[lower-alpha 1] after spending two months in jail. The Soviet government has executed his father and expropriated his family's property, including the apartment building. Leo's lover, Kira Argounova, welcomes him home and moves in with him, despite his status as a suspected counter-revolutionary.

A few months later, a panel led by Pavel Syerov questions Kira. They are evaluating the ideological suitability of students at the college where she studies engineering. She admits her bourgeois heritage and refuses to become an informant against Leo. Andrei Taganov, a GPU officer, expels her. After the meeting, Andrei tells Kira that he admires the bravery she showed in defying the panel. He hopes that in a future world everyone can express themselves openly, but until then people like her must suffer. Since she will lose her ration card for being expelled, he offers to get her a job in a railroad office.

Kira begs officials in the railroad office to help Leo go to a Crimean sanatorium for treatment of tuberculosis he contracted while in jail. They refuse to help a former aristocrat. Andrei comes to the office with Stepan Timoshenko to confront Andrei's old friend Syerov with evidence that he helps smuggle black market goods. Syerov promises to end his involvement. Kira asks Andrei for his help with Leo. He refuses, but when Kira becomes upset, he kisses her and admits he has been thinking about her since their previous meeting. Kira tells Andrei she loves him, but no one must know of their affair.

The second act begins six months later. Syerov is in charge of the railroad office and conspires with another official, Karp Morozov, to divert food shipments for the black market. They arrange for Leo, who has just returned from his treatment in Crimea (secretly funded by Andrei's gifts to Kira), to open a store that will sell the stolen goods. Kira warns Leo that his involvement could lead him to a firing squad. Andrei, who has supported Kira as his mistress, proposes marriage. In response, she suggests they should break up. He tells her it is too late for them to separate, because she has changed his view of life.

Timoshenko brings Andrei evidence of Syerov and Morozov's ongoing black market activities. Kira realizes this will implicate Leo as well. She asks Andrei to drop the case, but he refuses. Syerov and Morozov are arrested, but are not charged because they have influence with the local GPU chief. The chief orders Andrei to arrest Leo for a show trial and execution. Andrei is disillusioned by the corruption he has witnessed. When he goes to Leo's home to make the arrest, he discovers that Kira also lives there.

In the third act, after Leo's arrest, Kira finds Andrei preparing for a speech to a Communist Party meeting. She declares she is proud that she did what was necessary to save Leo from tuberculosis, and she expresses contempt for the Communist ideology that would have let him die. Andrei says he understands and accepts responsibility for making her suffer. When she leaves, Andrei confronts Syerov and insists that he use his influence to secure Leo's release. When Andrei gives his speech, he deviates from his prepared remarks to speak in favor of freedom and individualism.

Andrei commits suicide, and afterwards Kira admits to Leo that she was Andrei's mistress. Leo tells her that he is leaving town with Antonina Pavlovna, Morozov's former mistress, to be her gigolo. Kira says she will also leave to attempt an escape across the border. Leo warns that she will be killed, but she says she has already lost everything that matters, except her human spirit.

Cast and characters

The characters and cast from the Broadway production are given below:[31]

| Character | Broadway cast |

|---|---|

| Student | Paul Ballantyne |

| Boy Clerk | William Blees |

| G.P.U. Chief | Marshall Bradford |

| Comrade Sonia | Georgiana Brand |

| Comrade Voronov | Horace Cooper |

| Stepan Timoshenko | George Cotton |

| Kira Argounova | Helen Craig |

| Girl Clerk | Virginia Dunning |

| Upravdom | Cliff Dunstan |

| Leo Kovalensky | John Emery |

| Karp Morozov | Howard Freeman |

| Comrade Bitiuk | Ellen Hall |

| Andrei Taganov | Dean Jagger |

| Assistant G.P.U. Chief | Frank O'Connor |

| Soldier | John Parrish |

| Antonina Pavlovna | Lea Penman |

| Malashkin | Edwin Philips |

| Pavel Syerov | Arthur Pierson |

| Party Club Attendant | George Smith |

| Older Examiner | J. Ascher Smith |

| Neighbor | Ludmilla Toretzka |

Dramatic analysis

The play follows the basic plot and themes from We the Living. The plot in both is about a woman having an affair with a powerful man in order to save another man she loves. Rand acknowledged that similar plots had been used in many previous works of fiction, citing the opera Tosca as an example. She varied from traditional versions of the plot by making the powerful man an idealist who is in love with the woman and unaware of her other lover, rather than a villain who knowingly exploits her.[32] The play significantly streamlines the story: Kira's family is omitted, and the plot begins with her living with Leo. Some of the characterizations are also changed: Leo is more passive, and Andrei is portrayed less sympathetically.[33]

Aronson's sets were elaborate and expensive. He designed them to evoke pre-revolutionary Czarist architecture, but with a red color theme to reflect the use of that color by the Communists. A press report described them as "massive" and "decadent". The sets were placed on two 18-foot turntables that could be spun around to allow rapid changes between scenes.[34]

Reception and legacy

The play was a box office failure and received mostly negative reviews. Critics were positive about the acting and Aronson's set design, but strongly negative about the writing and direction.[26] Reviewer Arthur Pollock called the play "slow-moving, uninspired soup".[35] The New York Times described it as a "confusing" mixture of "sentimental melodrama" and political discussion.[31] A syndicated review by Ira Wolfert complained the story had "complications ... too numerous to mention".[36] A reviewer for The Hollywood Reporter quipped that the play was "as interminable as the five-year plan".[37]

Politically minded reviewers attacked the play from viewpoints across the political spectrum.[26] In the Communist Party USA magazine The New Masses, Alvah Bessie said the play was "deadly dull" and called Rand "a fourth-rate hack".[38] More centrist reviewers described the play as unrealistic, even when they sympathized with its message.[26] In the Catholic magazine Commonweal, Philip T. Hartung called the play "a confused muddle" and recommended the movie Ninotchka as better anti-Soviet entertainment.[39] From the right, New York World-Telegram drama critic Sidney B. Whipple complained the play understated the dangers of Communism.[37]

After the play's failure, Rand concluded her script was bad, and it was a mistake to attempt a theatrical adaptation of We the Living; she decided the novel "was not proper stage material".[40][41] She thought that Abbot was more suited to comedy than drama, and that his efforts as producer and director had made the play even worse.[42] Biographers of Rand have described the play as "a complete failure",[26] "a resounding flop",[43] and a "critical fiasco and professional embarrassment".[44] Theatre historian William Torbert Leonard described it as a "turgid adaptation" that "failed to enchant even the curious".[23]

The Unconquered was the last of Rand's plays to be produced in her lifetime, and she did not write any new plays after 1940.[40] She turned her attention to finishing her novel The Fountainhead, which was published in 1943 and became a bestseller.[45] Abbott, who had a long track record on Broadway, was not strongly impacted by the failure of The Unconquered. His next production, the crime drama Goodbye in the Night, written by Jerome Mayer, opened a few weeks later.[46]

Notes

- Petrograd, formerly known as Saint Petersburg, was renamed Leningrad in January 1924.[1] However, the city is referred to as "Petrograd" in Rand's script.[2]

- Sources differ about Leontovich's year of birth, but she was at least 39 when she was cast in the play.[19]

- Freeman was replaced by Ralph Morehouse for the remaining preview performances, but resumed the role on Broadway.[23]

References

- Branden 1986, p. 41

- Rand 2014, p. 182

- Britting 2004, pp. 14–20

- Britting 2004, pp. 29–30

- Britting 2004, pp. 34–36

- Heller 2009, pp. 92–93

- Burns 2009, p. 31

- Heller 2009, p. 95

- Britting 2014, pp. 336–337

- Heller 2009, pp. 101–102

- Collins 1993, p. 11

- Branden 1986, p. 150

- Britting 2014, p. 337

- "Russ Stage Artist Depicts Home Land". The Baltimore Sun. December 23, 1939. p. 20 – via Newspapers.com.

- Mayhew 2014, p. ix

- Heller 2009, p. 126

- Britting 2014, p. 338

- Heller 2009, p. 127

- Liebman 2017, p. 158

- Britting 2014, p. 339

- Leonard 1983, p. 483

- Kirkley 1939, p. 8

- Leonard 1983, p. 484

- Britting 2014, p. 342

- Branden 1986, p. 152

- Britting 2014, p. 344

- Heller 2009, p. 129

- Branden 1986, pp. 154–155

- Perinn 1990, p. 51

- Svanberg 2014

- "The Play: The Unconquered". The New York Times. February 14, 1940. p. 25.

- Rand 2000, p. 38

- Mayhew 2014, pp. viii–ix

- Britting 2014, pp. 339–340

- Pollock 1940, p. 6

- Wolfert 1940, p. 2

- Britting 2014, p. 346

- Bessie 1940, p. 29

- Hartung 1940, p. 412

- Britting 2014, p. 347

- Rand, Ayn. "The Publishing History of We the Living". Unpublished essay quoted in Ralston 2012, p. 168

- Branden 1986, pp. 150–151

- Burns 2009, p. 306

- Heller 2009, p. 133

- Branden 1986, pp. 180–181

- Mantle 1940, p. 35

Works cited

- Bessie, Alvah (February 27, 1940). "One for the Ashcan". New Masses. pp. 28–29.

- Branden, Barbara (1986). The Passion of Ayn Rand. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 0-385-19171-5. OCLC 12614728.

- Britting, Jeff (2004). Ayn Rand. Overlook Illustrated Lives series. New York: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 1-58567-406-0. OCLC 56413971.

- Britting, Jeff (2014). "Adapting We the Living for the Stage". In Mayhew, Robert (ed.). The Unconquered. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 335–347. ISBN 978-1-137-42873-8. OCLC 912971550.

- Burns, Jennifer (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7. OCLC 313665028.

- Collins, Glenn (April 3, 1993). "Eugenie Leontovich, 93, Actress, Playwright and Teacher, Is Dead". The New York Times. p. 11.

- Hartung, Philip T. (March 1, 1940). "The Stage and Screen: The Unconquered". Commonweal. p. 412.

- Heller, Anne C. (2009). Ayn Rand and the World She Made. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51399-9. OCLC 229027437.

- Kirkley, Donald (December 26, 1939). "The Stage". The Baltimore Sun. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- Leonard, William Torbert (1983). Broadway Bound: A Guide to Shows that Died Aborning. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1652-0. OCLC 239756089.

- Liebman, Roy (2017). Broadway Actors in Films, 1894-2015. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7685-5. OCLC 994710962.

- Mantle, Burns (March 19, 1940). "Goodbye in the Night Shiver Drama about Assorted Lunatics". Daily News. p. 35 – via Newspapers.com.

- Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2014). The Unconquered. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-42873-8. OCLC 912971550.

- Perinn, Vincent L. (1990). Ayn Rand: First Descriptive Bibliography. Rockville, Maryland: Quill & Brush. ISBN 0-9610494-8-0. OCLC 23216055.

- Pollock, Arthur (January 14, 1940). "The Unconquered Has Its Day – A Dull One". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ralston, Richard E. (2012). "Publishing We the Living". In Mayhew, Robert (ed.). Essays on Ayn Rand's We the Living (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. pp. 159–170. ISBN 978-0-7391-4969-0. OCLC 769323240.

- Rand, Ayn (2000). Boeckmann, Tore (ed.). The Art of Fiction: A Guide for Writers and Readers. New York: Plume. ISBN 0-452-28154-7. OCLC 934792412.

- Rand, Ayn (2014). "The Unconquered (1939/40)". In Mayhew, Robert (ed.). The Unconquered. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 181–289. ISBN 978-1-137-42873-8. OCLC 912971550.

- Svanberg, Carl (September 18, 2014). "Introducing Ayn Rand's The Unconquered". Impact Today. Ayn Rand Institute. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Wolfert, Ira (February 18, 1940). "The Unconquered Is Full of Complications". The Indianapolis Star. North American Newspaper Alliance. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.