Atlas Shrugged

Atlas Shrugged is a 1957 novel by Ayn Rand. Rand's fourth and final novel, it was also her longest, and the one she considered to be her magnum opus in the realm of fiction writing.[1] Atlas Shrugged includes elements of science fiction, mystery, and romance, and it contains Rand's most extensive statement of Objectivism in any of her works of fiction. The theme of Atlas Shrugged, as Rand described it, is "the role of man's mind in existence". The book explores a number of philosophical themes from which Rand would subsequently develop Objectivism. In doing so, it expresses the advocacy of reason, individualism, and capitalism, and depicts what Rand saw to be the failures of governmental coercion.

_-_Ayn_Rand.jpg.webp) First edition | |

| Author | Ayn Rand |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | |

| Published | October 10, 1957 |

| Publisher | Random House |

| Pages | 1,168 (first edition) |

| OCLC | 412355486 |

The book depicts a dystopian United States in which private businesses suffer under increasingly burdensome laws and regulations. Railroad executive Dagny Taggart and her lover, steel magnate Hank Rearden, struggle against "looters" who want to exploit their productivity. Dagny and Hank discover that a mysterious figure called John Galt is persuading other business leaders to abandon their companies and disappear as a strike of productive individuals against the looters. The novel ends with the strikers planning to build a new capitalist society based on Galt's philosophy of reason and individualism.

Atlas Shrugged received largely negative reviews after its 1957 publication, but achieved enduring popularity and ongoing sales in the following decades. After several unsuccessful attempts to adapt the novel for film or television, a film trilogy based on it was released from 2011 to 2014. The book has also achieved currency among libertarian and conservative thinkers and politicians.

Synopsis

Setting

Atlas Shrugged is set in a dystopian United States at an unspecified time, in which the country has a "National Legislature" instead of Congress and a "Head of State" instead of a President. The United States also appears to be approaching an economic collapse, with widespread shortages, constant business failures, and severely decreased productivity. The government has gradually extended its control over businesses by passing ever more stringent regulations that increasingly favor established and stagnant corporations, especially those that have good connections in Washington. Writer Edward Younkins said, "The story may be simultaneously described as anachronistic and timeless. The pattern of industrial organization appears to be that of the late 1800s—the mood seems to be close to that of the depression-era 1930s. Both the social customs and the level of technology remind one of the 1950s".[2] Many early 20th-century technologies are available, and the steel and railroad industries are especially significant; but later technologies such as jet planes and computers are largely absent.[3] There is very little mention of historical people or events, not even major events such as World War II.[4] Aside from the United States, most countries are referred to as "People's States" that are implied to be either socialist or communist.[2][5]

Plot

Dagny Taggart, the operating vice-president of Taggart Transcontinental railroad, keeps the company going amid a sustained economic depression. As economic conditions worsen and government enforces statist controls on successful businesses, people are heard repeating the cryptic phrase "Who is John Galt?" which means: "Don't ask questions nobody can answer";[6] or more broadly, "Why bother?". Her brother James, the railroad's president, seems to make irrational decisions, such as buying from Orren Boyle's unreliable Associated Steel. Dagny is also disappointed to discover that the Argentine billionaire Francisco d'Anconia, her childhood friend and first love, is risking his family's copper company by constructing the San Sebastián copper mines, even though Mexico will probably nationalize them. Despite the risk, Jim and Boyle invest heavily in a railway for the region while ignoring the Rio Norte Line in Colorado, where entrepreneur Ellis Wyatt has discovered large oil reserves. Mexico nationalizes the mines and railroad line, but the mines are discovered to be worthless. To recoup the railroad's losses, Jim influences the National Alliance of Railroads to prohibit competition in prosperous areas such as Colorado. Wyatt demands that Dagny supply adequate rails to his wells before the ruling takes effect.

In Philadelphia, self-made steel magnate Hank Rearden develops Rearden Metal, an alloy lighter and stronger than conventional steel. Dagny opts to use Rearden Metal in the Rio Norte Line, becoming the first major customer for the product. After Hank refuses to sell the metal to the State Science Institute, a government research foundation run by Dr. Robert Stadler, the Institute publishes a report condemning the metal without identifying problems with it. As a result, many significant organizations boycott the line. Although Stadler agrees with Dagny's complaints about the unscientific tone of the report, he refuses to override it. To protect Taggart Transcontinental from the boycott, Dagny decides to build the Rio Norte Line as an independent company named the John Galt Line.

Hank is attracted to Dagny and is unhappy with his manipulative wife Lillian, but feels obliged to stay with her. When he joins Dagny for the successful inauguration of the John Galt Line, they become lovers. On a vacation trip, Hank and Dagny discover an abandoned factory that contains an incomplete but revolutionary motor that runs on atmospheric static electricity. They begin searching for the inventor, and Dagny hires scientist Quentin Daniels to reconstruct the motor. However, a series of economically harmful directives are issued by Wesley Mouch, a former Rearden lobbyist who betrayed Hank in return for a job leading a government agency. In response, Wyatt sets his wells on fire and disappears. Several other important business leaders have disappeared, leaving their industries to failure.

From conversations with Francisco, Dagny and Hank realize he is hurting his copper company intentionally, although they do not understand why. When the government imposes a directive that forbids employees from leaving their jobs and nationalizes all patents, Dagny violates the law by resigning in protest. To gain Hank's compliance, the government blackmails him with threats to publicize his affair with Dagny. After a major disaster in one of Taggart Transcontinental's tunnels, Dagny decides to return to work. On her return, she receives notice that Quentin Daniels is also quitting in protest, and she rushes across the country to convince him to stay.

On her way to Daniels, Dagny meets a hobo with a story that reveals the secret of the motor: it was invented and abandoned by an engineer named John Galt, who is the inspiration for the common saying. When she chases after Daniels in a private plane, she crashes and discovers the secret behind the disappearances of business leaders: Galt is leading an organized strike of "the men of the mind" against a society that demands that they be sacrificed. She has crashed in their hiding place, an isolated valley known as Galt's Gulch. As she recovers from her injuries, she hears the strikers' explanations for the strike, and learns that the strikers include Francisco and many prominent people, such as her favorite composer, Richard Halley, and infamous pirate Ragnar Danneskjöld. Dagny falls in love with Galt, who asks her to join the strike.

Reluctant to abandon her railroad, Dagny leaves Galt's Gulch, but finds the government has devolved into dictatorship. Francisco has finished sabotaging his mines and quits. After he helps stop an armed government takeover of Hank's steel mill, Francisco convinces Hank to join the strike. Galt follows Dagny to New York, where he hacks into a national radio broadcast to deliver a three-hour speech that explains the novel's theme and Rand's Objectivism.[7] The authorities capture Galt, but he is rescued by his partisans. The government collapses and New York City loses its electricity. The novel closes as Galt announces that the way is clear for the strikers to rejoin the world.

History

Early novel idea in Russia

Rand biographer Anne Heller traces the ideas which would go into Atlas Shrugged all the way back to a novel which the young Rand had in mind when a student at the University of Petrograd, long before she came to America. That novel - of which Rand prepared a detailed outline, though she never wrote it - was set in a future in which the whole of Europe had become communist. A beautiful, spirited American heiress is luring the most talented Europeans to America, thereby weakening the European communist regime. After various complicated plot twists - the heiress seduces a French communist who was sent to America to stop her, and they have a stormy love affair - the novel would have gotten to a happy end, i.e. the collapse of European communism. The main difference from Atlas Shrugged as written many years later was that while in Russia, Rand idealized America as a capitalist paradise and did not realize that it might have its own home-grown communists and socialists; therefore, in the book as finally written, talented people could not just cross the Atlantic, but needed to withdraw to an isolated valley. The most clear continuity is the fact that already in that early Russian version, the protagonist heiress would have had an assistant called Eddie Willers, the name of Dagny Taggart's assistant in Atlas Shrugged. [8]

Context and writing

Rand's stated goal for writing the novel was "to show how desperately the world needs prime movers and how viciously it treats them" and to portray "what happens to the world without them".[9] The core idea for the book came to her after a 1943 telephone conversation with her friend Isabel Paterson, who asserted that Rand owed it to her readers to write fiction about her philosophy. Rand replied, "What if I went on strike? What if all the creative minds of the world went on strike?"[10] Rand then began Atlas Shrugged to depict the morality of rational self-interest,[11] by exploring the consequences of a strike by intellectuals refusing to supply their inventions, art, business leadership, scientific research, or new ideas to the rest of the world.[12]

Rand began the first draft of the novel on September 2, 1946.[13] She initially thought it would be easy to write and completed quickly, but as she considered the complexity of the philosophical issues she wanted to address, she realized it would take longer.[14] After ending a contract to write screenplays for Hal Wallis and finishing her obligations for the film adaptation of The Fountainhead, Rand was able to work full-time on the novel that she tentatively titled The Strike. By the summer of 1950, she had written 18 chapters;[15] by September 1951, she had written 21 chapters and was working on the last of the novel's three sections.[16]

As Rand completed new chapters, she read them to a circle of young confidants who had begun gathering at her home to discuss philosophy. This group included Nathaniel Branden, his wife Barbara Branden, Barbara's cousin Leonard Peikoff, and economist Alan Greenspan.[17] Progress on the novel slowed considerably in 1953, when Rand began working on Galt's lengthy radio address. She spent more than two years completing the speech, finishing it on October 13, 1955.[18] The remaining chapters proceeded more quickly, and by November 1956 Rand was ready to submit the almost-completed manuscript to publishers.[19]

Atlas Shrugged was Rand's last completed work of fiction. It marked a turning point in her life—the end of her career as a novelist and the beginning of her role as a popular philosopher.[20][21]

Influences

To depict the industrial setting of Atlas Shrugged, Rand conducted research on the American railroad and steel industries. She toured and inspected a number of industrial facilities, such as the Kaiser Steel plant,[22] visited facilities of the New York Central Railroad,[23][24] and even briefly operated a locomotive on the Twentieth Century Limited.[25] Rand also used previous research she did for a proposed (but never completed) screenplay about the development of the atomic bomb, including her interviews of J. Robert Oppenheimer, which influenced the character Robert Stadler and the novel's depiction of the development of "Project X".[26]

Rand's descriptions of Galt's Gulch were based on the town of Ouray, Colorado, which Rand and her husband visited in 1951 when they were relocating from Los Angeles to New York.[16] Other details of the novel were affected by the experiences and comments of her friends. For example, her portrayal of leftist intellectuals (such as the characters Balph Eubank and Simon Pritchett) was influenced by the college experiences of Nathaniel and Barbara Branden,[27] and Alan Greenspan provided information on the economics of the steel industry.[28]

Libertarian writer Justin Raimondo described similarities between Atlas Shrugged and Garet Garrett's 1922 novel The Driver, which is about an idealized industrialist named Henry Galt, who is a transcontinental railway owner trying to improve the world and fighting against government and socialism.[29] Raimondo believed the earlier novel influenced Rand's writing in ways she failed to acknowledge, although there was no "word-for-word plagiarism“ and The Driver was published four years before Rand emigrated to the United States.[30] Journalist Jeff Walker echoed Raimondo's comparisons in his book The Ayn Rand Cult and listed The Driver as one of several unacknowledged precursors to Atlas Shrugged.[31] In contrast, Chris Matthew Sciabarra said he "could not find any evidence to link Rand to Garrett"[32] and considered Raimondo's claims to be "unsupported".[33] Liberty magazine editor R. W. Bradford said Raimondo made an unconvincing comparison based on a coincidence of names and common literary devices.[34] Stephan Kinsella doubted that Rand was in any way influenced by Garrett.[35] Writer Bruce Ramsey said both novels "have to do with running railroads during an economic depression, and both suggest pro-capitalist ways in which the country might get out of the depression. But in plot, character, tone, and theme they are very different."[36]

Publishing history

Due to the success of Rand's 1943 novel The Fountainhead, she had no trouble attracting a publisher for Atlas Shrugged. This was a contrast to her previous novels, which she had struggled to place. Even before she began writing it, she had been approached by publishers interested in her next novel. However, her contract for The Fountainhead gave the first option to its publisher, Bobbs-Merrill Company. After reviewing a partial manuscript, they asked her to discuss cuts and other changes. She refused, and Bobbs-Merrill rejected the book.[37]

Hiram Hayden, an editor she liked who had left Bobbs-Merrill, asked her to consider his new employer, Random House. In an early discussion about the difficulties of publishing a controversial novel, Random House president Bennett Cerf proposed that Rand should submit the manuscript to multiple publishers simultaneously and ask how they would respond to its ideas, so she could evaluate who might best promote her work. Rand was impressed by the bold suggestion and by her overall conversations with them. After speaking with a few other publishers from about a dozen who were interested, Rand decided multiple submissions were not needed; she offered the manuscript to Random House. Upon reading the portion Rand submitted, Cerf declared it a "great book" and offered Rand a contract. It was the first time Rand had worked with a publisher whose executives seemed enthusiastic about one of her books.[38]

Random House published the novel on October 10, 1957. The initial print run was 100,000 copies. The first paperback edition was published by New American Library in July 1959, with an initial run of 150,000.[39] A 35th-anniversary edition was published by E. P. Dutton in 1992, with an introduction by Rand's heir, Leonard Peikoff.[40] The novel has been translated into more than 25 languages.[lower-alpha 1]

Title and chapters

The working title of the novel was The Strike, but Rand thought this title would reveal the mystery element of the novel prematurely.[12] She was pleased when her husband suggested Atlas Shrugged, previously the title of a single chapter, for the book.[42] The title is a reference to Atlas, a Titan in Greek mythology, who is described in the novel as "the giant who holds the world on his shoulders".[lower-alpha 2] The significance of this reference appears in a conversation between the characters Francisco d'Anconia and Hank Rearden, in which d'Anconia asks Rearden what advice he would give Atlas upon seeing "the greater [the Titan's] effort, the heavier the world bore down on his shoulders". With Rearden unable to answer, d'Anconia gives his own advice: "To shrug".[44]

The novel is divided into three parts consisting of ten chapters each. Each part is named in honor of one of Aristotle's laws of logic: "Non-Contradiction" after the law of noncontradiction; "Either-Or", which is a reference to the law of excluded middle; and "A Is A" in reference to the law of identity.[45] Each chapter also has a title; Atlas Shrugged is the only one of Rand's novels to use chapter titles.[46]

Themes

Philosophy

The story of Atlas Shrugged dramatically expresses Rand's ethical egoism, her advocacy of "rational selfishness", whereby all of the principal virtues and vices are applications of the role of reason as man's basic tool of survival (or a failure to apply it): rationality, honesty, justice, independence, integrity, productiveness, and pride. Rand's characters often personify her view of the archetypes of various schools of philosophy for living and working in the world. Robert James Bidinotto wrote, "Rand rejected the literary convention that depth and plausibility demand characters who are naturalistic replicas of the kinds of people we meet in everyday life, uttering everyday dialogue and pursuing everyday values. But she also rejected the notion that characters should be symbolic rather than realistic."[47] and Rand herself stated, "My characters are never symbols, they are merely men in sharper focus than the audience can see with unaided sight. ... My characters are persons in whom certain human attributes are focused more sharply and consistently than in average human beings".[47]

In addition to the plot's more obvious statements about the significance of industrialists to society, and the sharp contrast to Marxism and the labor theory of value, this explicit conflict is used by Rand to draw wider philosophical conclusions, both implicit in the plot and via the characters' own statements. Atlas Shrugged caricatures fascism, socialism, communism, and any state intervention in society, as allowing unproductive people to "leech" the hard-earned wealth of the productive, and Rand contends that the outcome of any individual's life is purely a function of their ability, and that any individual could overcome adverse circumstances, given ability and intelligence.[48]

Sanction of the victim

The concept "sanction of the victim" is defined by Leonard Peikoff as "the willingness of the good to suffer at the hands of the evil, to accept the role of sacrificial victim for the 'sin' of creating values".[49] Accordingly, throughout Atlas Shrugged, numerous characters are frustrated by this sanction, as when Hank Rearden appears duty-bound to support his family, despite their hostility toward him; later, the principle is stated by Dan Conway: "I suppose somebody's got to be sacrificed. If it turned out to be me, I have no right to complain". John Galt further explains the principle: "Evil is impotent and has no power but that which we let it extort from us", and, "I saw that evil was impotent ... and the only weapon of its triumph was the willingness of the good to serve it".[50]

Government and business

Rand's view of the ideal government is expressed by John Galt: "The political system we will build is contained in a single moral premise: no man may obtain any values from others by resorting to physical force", whereas "no rights can exist without the right to translate one's rights into reality—to think, to work and to keep the results—which means: the right of property".[51] Galt himself lives a life of laissez-faire capitalism.[52]

In the world of Atlas Shrugged, society stagnates when independent productive agencies are socially demonized for their accomplishments. This is in agreement with an excerpt from a 1964 interview with Playboy magazine, in which Rand states: "What we have today is not a capitalist society, but a mixed economy—that is, a mixture of freedom and controls, which, by the presently dominant trend, is moving toward dictatorship. The action in Atlas Shrugged takes place at a time when society has reached the stage of dictatorship. When and if this happens, that will be the time to go on strike, but not until then".[53]

Rand also depicts public choice theory, such that the language of altruism is used to pass legislation nominally in the public interest (e.g., the "Anti-Dog-Eat-Dog Rule", and "The Equalization of Opportunity Bill"), but more to the short-term benefit of special interests and government agencies.[54]

Property rights and individualism

Rand's heroes continually oppose "parasites", "looters", and "moochers" who demand the benefits of the heroes' labor. Edward Younkins describes Atlas Shrugged as "an apocalyptic vision of the last stages of conflict between two classes of humanity—the looters and the non-looters. The looters are proponents of high taxation, big labor, government ownership, government spending, government planning, regulation, and redistribution".[55]

"Looters" are Rand's depiction of bureaucrats and government officials, who confiscate others' earnings by the implicit threat of force ("at the point of a gun"). Some officials execute government policy, such as those who confiscate one state's seed grain to feed the starving citizens of another; others exploit those policies, such as the railroad regulator who illegally sells the railroad's supplies for his own profit. Both use force to take property from the people who produced or earned it.

"Moochers" are Rand's depiction of those unable to produce value themselves, who demand others' earnings on behalf of the needy, but resent the talented upon whom they depend, and appeal to "moral right" while enabling the "lawful" seizure by governments.

The character Francisco d'Anconia indicates the role of "looters" and "moochers" in relation to money: "So you think that money is the root of all evil? ... Have you ever asked what is the root of money? Money is a tool of exchange, which can't exist unless there are goods produced and men able to produce them. ... Money is not the tool of the moochers, who claim your product by tears, or the looters who take it from you by force. Money is made possible only by the men who produce."[56]

Genre

The novel includes elements of mystery, romance, and science fiction.[57][58] Rand referred to Atlas Shrugged as a mystery novel, "not about the murder of man's body, but about the murder—and rebirth—of man's spirit".[59] Nonetheless, when asked by film producer Albert S. Ruddy if a screenplay could focus on the love story, Rand agreed and reportedly said, "That's all it ever was".[58]

Technological progress and intellectual breakthroughs in scientific theory appear in Atlas Shrugged, leading some observers to classify it in the genre of science fiction.[60] Writer Jeff Riggenbach notes: "Galt's motor is one of the three inventions that propel the action of Atlas Shrugged", the other two being Rearden Metal and the government's sonic weapon, Project X.[61] Other fictional technologies are "refractor rays" (to disguise Galt's Gulch), a sophisticated electrical torture device (the Ferris Persuader), voice-activated door locks (at the Gulch's power station), palm-activated door locks (in Galt's New York laboratory), Galt's means of quietly turning the entire contents of his laboratory into a fine powder when a lock is breached, and a means of taking over all radio stations worldwide. Riggenbach adds, "Rand's overall message with regard to science seems clear: the role of science in human life and human society is to provide the knowledge on the basis of which technological advancement and the related improvements in the quality of human life can be realized. But science can fulfill this role only in a society in which human beings are left free to conduct their business as they see fit."[62] Science fiction historian John J. Pierce describes it as a "romantic suspense novel" that is "at least a borderline case" of science fiction.[63]

Reception

Sales

Atlas Shrugged debuted at number 13 on The New York Times Best Seller list three days after its publication. It peaked at number 3 on December 8, 1957, and was on the list for 22 consecutive weeks.[64] By 1984, its sales had exceeded five million copies.[65]

Sales of Atlas Shrugged increased following the 2007 financial crisis. The Economist reported that the 52-year-old novel ranked 33rd among Amazon.com's top-selling books on January 13, 2009, and that its 30-day sales average showed the novel selling three times faster than during the same period of the previous year. On April 2, 2009, Atlas Shrugged ranked first in the "Fiction and Literature" category at Amazon and fifteenth in overall sales.[66][67] Total sales of the novel in 2009 exceeded 500,000 copies.[68] The book sold 445,000 copies in 2011, the second-strongest sales year in the novel's history.[69]

Contemporary reviews

Atlas Shrugged was generally disliked by critics. Rand scholar Mimi Reisel Gladstein later wrote that "reviewers seemed to vie with each other in a contest to devise the cleverest put-downs"; one called it "execrable claptrap", while another said it showed "remorseless hectoring and prolixity".[70] In the Saturday Review, Helen Beal Woodward said that the novel was written with "dazzling virtuosity" but was "shot through with hatred".[71] In The New York Times Book Review, Granville Hicks similarly said the book was "written out of hate".[72] The reviewer for Time magazine asked: "Is it a novel? Is it a nightmare? Is it Superman – in the comic strip or the Nietzschean version?"[73] In the National Review, Whittaker Chambers called Atlas Shrugged "sophomoric"[74] and "remarkably silly",[75] and said it "can be called a novel only by devaluing the term".[74] Chambers argued against the novel's implicit endorsement of atheism and said the implicit message of the novel is akin to "Hitler's National Socialism and Stalin's brand of Communism": "To a gas chamber—go!"[76]

There were some positive reviews. Richard McLaughlin, reviewing the novel for The American Mercury, described it as a "long overdue" polemic against the welfare state with an "exciting, suspenseful plot", although unnecessarily long. He drew a comparison with the antislavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, saying that a "skillful polemicist" did not need a refined literary style to have a political impact.[77] Journalist and book reviewer John Chamberlain, writing in the New York Herald Tribune, found Atlas Shrugged satisfying on many levels: as science fiction, as a "philosophical detective story", and as a "profound political parable".[78]

Influence and legacy

Atlas Shrugged has attracted an energetic and committed fan base. Each year, the Ayn Rand Institute donates 400,000 copies of works by Rand, including Atlas Shrugged, to high school students.[59] According to a 1991 survey done for the Library of Congress and the Book of the Month Club, Atlas Shrugged was mentioned among the books that made the most difference in the lives of 17 out of 5,000 Book-of-the-Month club members surveyed, which placed the novel between the Bible and M. Scott Peck's The Road Less Traveled.[79] Modern Library's 1998 nonscientific online poll of the 100 best novels of the 20th century[80][81] found Atlas rated No. 1, although it was not included on the list chosen by the Modern Library board of authors and scholars.[82] The 2018 PBS Great American Read television series found Atlas rated number 20 out of 100 novels.[83]

Rand's impact on contemporary libertarian thought has been considerable. The title of one libertarian magazine, Reason: Free Minds, Free Markets, is taken directly from John Galt, the hero of Atlas Shrugged, who argues that "a free mind and a free market are corollaries". In a tribute written on the 20th anniversary of the novel's publication, libertarian philosopher John Hospers praised it as "a supreme achievement, guaranteed of immortality".[84] In 1983, the Libertarian Futurist Society gave the novel one of its first "Hall of Fame" awards.[85] In 1997, the libertarian Cato Institute held a joint conference with The Atlas Society, an Objectivist organization, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the publication of Atlas Shrugged.[86] At this event, Howard Dickman of Reader's Digest stated that the novel had "turned millions of readers on to the ideas of liberty" and said that the book had the important message of the readers' "profound right to be happy".[86]

Former Rand business partner and lover Nathaniel Branden has expressed differing views of Atlas Shrugged. He was initially quite favorable to it, and even after he and Rand ended their relationship, he still referred to it in an interview as "the greatest novel that has ever been written", although he found "a few things one can quarrel with in the book".[87] However, in 1984 he argued that Atlas Shrugged "encourages emotional repression and self-disowning" and that Rand's works contained contradictory messages. He criticized the potential psychological impact of the novel, stating that John Galt's recommendation to respond to wrongdoing with "contempt and moral condemnation" clashes with the view of psychologists who say this only causes the wrongdoing to repeat itself.[88]

The Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises admired the unapologetic elitism he saw in Rand's work. In a letter to Rand written a few months after the novel's publication, he said it offered "a cogent analysis of the evils that plague our society, a substantiated rejection of the ideology of our self-styled 'intellectuals' and a pitiless unmasking of the insincerity of the policies adopted by governments and political parties ... You have the courage to tell the masses what no politician told them: you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions which you simply take for granted you owe to the efforts of men who are better than you."[89]

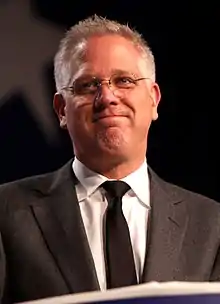

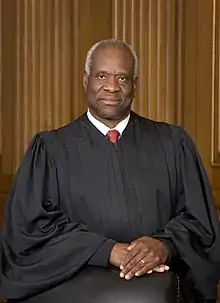

In the years immediately following the novel's publication, many American conservatives, such as William F. Buckley, Jr., strongly disapproved of Rand and her Objectivist message.[90] In addition to the strongly critical review by Whittaker Chambers, Buckley solicited a number of critical pieces: Russell Kirk called Objectivism an "inverted religion",[90] Frank Meyer accused Rand of "calculated cruelties" and her message, an "arid subhuman image of man",[90] and Garry Wills regarded Rand a "fanatic".[90] In the late 2000s, however, conservative commentators suggested the book as a warning against a socialistic reaction to the finance crisis. Conservative commentators Neal Boortz,[91] Glenn Beck, and Rush Limbaugh[92] offered praise of the book on their respective radio and television programs. In 2006, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Clarence Thomas cited Atlas Shrugged as among his favorite novels.[93] Republican Congressman John Campbell said, for example, "People are starting to feel like we're living through the scenario that happened in [the novel] ... We're living in Atlas Shrugged", echoing Stephen Moore in an article published in The Wall Street Journal on January 9, 2009, titled "Atlas Shrugged From Fiction to Fact in 52 Years".[94]

In 2005, Republican Congressman Paul Ryan said that Rand was "the reason I got into public service", and he later required his staff members to read Atlas Shrugged.[95][96] In April 2012, he disavowed such beliefs however, calling them "an urban legend", and rejected Rand's philosophy.[97] Ryan was subsequently mocked by Nobel Prize-winning economist and liberal commentator Paul Krugman for his reportedly getting ideas about monetary policy from the novel.[98] In another commentary, Krugman quoted a quip by writer John Rogers: "There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year-old's life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs."[99]

References to Atlas Shrugged have appeared in a variety of other popular entertainments. In the first season of the drama series Mad Men, Bert Cooper urges Don Draper to read the book, and Don's sales pitch tactic to a client indicates he has been influenced by the strike plot: "If you don't appreciate my hard work, then I will take it away and we'll see how you do."[100] Less positive mentions of the novel occur in the animated comedy Futurama, where it appears among the library of books flushed down to the sewers to be read only by grotesque mutants, and in South Park, where a newly literate character gives up on reading after experiencing Atlas Shrugged.[101] BioShock, a critically acclaimed 2007 video game, is widely considered to be a response to Atlas Shrugged. The story depicts a collapsed Objectivist society, and significant characters in the game owe their naming to Rand's work, which game creator Ken Levine said he found "really fascinating".[102]

In 2013, it was announced that Galt's Gulch, Chile, a settlement for libertarian devotees named for John Galt's safe haven, would be established near Santiago, Chile,[103] but the project collapsed amid accusations of fraud[104][105] and lawsuits filed by investors.[106]

Adaptations

A film adaptation of Atlas Shrugged was in "development hell" for nearly 40 years.[107] In 1972, Albert S. Ruddy approached Rand to produce a cinematic adaptation. Rand insisted on having final script approval, which Ruddy refused to give her, thus preventing a deal. In 1978, Henry and Michael Jaffe negotiated a deal for an eight-hour Atlas Shrugged television miniseries on NBC. Michael Jaffe hired screenwriter Stirling Silliphant to adapt the novel and he obtained approval from Rand on the final script. When Fred Silverman became president of NBC in 1979, the project was scrapped.[108]

Rand, a former Hollywood screenwriter herself, began writing her own screenplay, but died in 1982 with only one-third of it finished. She left her estate, including the film rights to Atlas, to Leonard Peikoff, who sold an option to Michael Jaffe and Ed Snider. Peikoff would not approve the script they wrote, and the deal fell through. In 1992, investor John Aglialoro bought an option to produce the film, paying Peikoff over $1 million for full creative control.[108] Two new scripts – one by screenwriter Benedict Fitzgerald and another by Peikoff's wife, Cynthia Peikoff – were deemed inadequate, and Aglialoro refunded early investors in the project.[109]

In 1999, under Aglialoro's sponsorship, Ruddy negotiated a deal with Turner Network Television (TNT) for a four-hour miniseries, but the project was killed after TNT merged with AOL Time Warner. After the TNT deal fell through, Howard and Karen Baldwin obtained the rights while running Philip Anschutz's Crusader Entertainment. The Baldwins left Crusader to form Baldwin Entertainment Group in 2004 and took the rights to Atlas Shrugged with them. Michael Burns of Lions Gate Entertainment approached the Baldwins to fund and distribute Atlas Shrugged.[108] A draft screenplay was written by James V. Hart[110] and rewritten by Randall Wallace,[111] but was never produced.

Atlas Shrugged: Part I

In May 2010, Brian Patrick O'Toole and Aglialoro wrote a screenplay, intent on filming in June 2010. Stephen Polk was set to direct.[112] However, Polk was fired and principal photography began on June 13, 2010, under the direction of Paul Johansson and produced by Harmon Kaslow and Aglialoro.[113] This resulted in Aglialoro's retention of his rights to the property, which were set to expire on June 15, 2010. Filming was completed on July 20, 2010,[114] and the movie was released on April 15, 2011.[115] Taylor Schilling played Dagny Taggart and Grant Bowler played Hank Rearden.[116]

The film was met with a generally negative reception from professional critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 12% based on 51 reviews, with an average score of 3.6 out of 10.[117] The film had under $5 million in total box office receipts,[115] considerably less than the estimated $20 million invested by Aglialoro and others.[118] The poor box office and critical reception made Aglialoro reconsider his plans for the rest of the trilogy,[119] but other investors convinced him to continue.[120]

Atlas Shrugged: Part II

On February 2, 2012, Kaslow and Aglialoro announced they had raised $16 million to fund Atlas Shrugged: Part II.[121] Principal photography began on April 2, 2012;[122] the producers hoped to release the film before the US presidential election in November.[123] Because the cast for the first film had not been contracted for the entire trilogy, different actors were cast for all the roles.[124] Samantha Mathis played Dagny Taggart, with Jason Beghe as Henry Rearden and Esai Morales as Francisco d'Anconia.[125]

The film was released on October 12, 2012, without a special screening for critics.[126] It earned $1.7 million on 1012 screens for the opening weekend, which at that time ranked as the 109th worst opening for a film in wide release.[127] Critical response was highly negative; Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a 4% rating based on 23 reviews, with an average score of 3 out of 10.[128] The film's final box office total was $3.3 million.[127]

Atlas Shrugged: Part III: Who Is John Galt?

The third part in the series, Atlas Shrugged Part III: Who Is John Galt?, was released on September 12, 2014.[129] The movie opened on 242 screens and grossed $461,197 its opening weekend.[130] It was panned by critics, holding a 0% at Rotten Tomatoes, based on ten reviews.[131]

Dagny Taggart was played by Laura Regan, Henry Rearden by Rob Morrow, John Galt by Kristoffer Polaha, and Francisco d'Anconia by Joaquim de Almeida.

See also

Notes

- According to the Ayn Rand Institute, Atlas Shrugged has been translated into Albanian, Bulgarian, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Marathi, Mongolian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Ukrainian.[39][41]

- In ancient myths, Atlas supported the sky, not the earth. Artistic depictions of Atlas holding a sphere (representing the sky) led to a later misconception that he held the earth.[43]

References

- Rand 1997, p. 704

- Younkins, Edward W. "Atlas Shrugged: Ayn Rand's Philosophical and Literary Masterpiece". In Younkins 2007, pp. 9–10

- Hunt 1983, p. 85

- Hunt 1983, p. 86

- Hunt 1983, p. 82

- Rand 1995, p. 23

- Stolyarov II, G. "The Role and Essence of John Galt's Speech in Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged". In Younkins 2007, p. 99

- Heller 2009, p. 48-49

- Rand 1997, p. 392

- Heller 2009, p. 165

- Rand, Ayn (1986). Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. Signet. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-451-14795-0.

- Branden 1986, p. 291

- Heller 2009, p. 201

- Heller 2009, p. 202

- Heller 2009, p. 229

- Heller 2009, p. 235

- Branden 1986, pp. 254–255

- Heller 2009, pp. 260, 268

- Heller 2009, p. 271

- Younkins 2007, p. 1

- Gladstein 2000, p. 28

- Burns 2009, p. 126

- Heller 2009, p. 206

- Burns 2009, p. 125

- Heller 2009, p. 212

- Burns 2009, p. 107

- Heller 2009, p. 225

- Heller 2009, p. 242

- Raimondo 2008, pp. 237–241

- Raimondo 2008, p. 243

- Walker 1999, pp. 305–307

- Sciabarra 2013, p. 419

- Sciabarra 1999, p. 11

- Bradford 1994, pp. 57–58

- Kinsella 2007

- Ramsey 2008

- Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing Atlas Shrugged". In Mayhew 2009, pp. 123–124

- Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing Atlas Shrugged". In Mayhew 2009, pp. 124–127

- Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing Atlas Shrugged". In Mayhew 2009, p. 130

- Gladstein 1999, p. 129

- "Foreign Editions" (PDF). Ayn Rand Institute. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- Burns 2009, p. 149

- Hansen 2004, p. 127

- Minsaas, Kirsti. "Ayn Rand's Recasting of Ancient Myths in Atlas Shrugged". In Younkins 2007, pp. 131–132

- Younkins, Edward W. "Atlas Shrugged: Ayn Rand's Philosophical and Literary Masterpiece". In Younkins 2007, p. 15

- Seddon, Fred. "Various Levels of Meaning in the Chapter Titles of Atlas Shrugged". In Younkins 2007, p. 47

- Bidinotto, Robert James (April 5, 2011). "Atlas Shrugged as Literature". The Atlas Society. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- Peikoff, Leonard. "Introduction to the 35th Anniversary Edition". In Rand, Ayn (1996) [1957]. Atlas Shrugged (35th anniversary ed.). New York: Signet. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-0-451-19114-4.

- Leonard Peikoff, "The Philosophy of Objectivism" lecture series (1976), Lecture 8.

- Rand 1992, p. 1048

- Rand 1992, p. 1062

- Gladstein 1999, p. 54

- "Ayn Rand interviewed by Alvin Toffler". Playboy Magazine. discoveraynrand.com. 1964. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- Caplan, Bryan. "Atlas Shrugged and Public Choice: The Obvious Parallels". In Younkins 2007, pp. 215–224

- Younkins, Edward W. "Atlas Shrugged: Ayn Rand's Philosophical and Literary Masterpiece". In Younkins 2007, p. 10

- Rand 1992, pp. 410–413

- Gladstein 1999, p. 42

- McConnell 2010, p. 507

- Rubin, Harriet (September 15, 2007). "Ayn Rand's Literature of Capitalism". The New York Times.

- Hunt 1983, pp. 80–98

- Riggenbach, Jeff. "Atlas Shrugged as a Science Fiction Novel". In Younkins 2007, p. 124

- Riggenbach, Jeff. "Atlas Shrugged as a Science Fiction Novel". In Younkins 2007, p. 126

- Pierce 1989, pp. 158–159

- "History of Atlas Shrugged". Ayn Rand Institute. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- Branden 1986, p. 299

- "The Atlas Shrugged Index". Freakonomics Blog. The New York Times. March 9, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- "Atlas felt a sense of déjà vu". The Economist. February 26, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- "Atlas Shrugged Sets a New Record!". Ayn Rand Institute. January 21, 2010. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- "Atlas Shrugged Still Flying Off Shelves". Ayn Rand Institute. February 14, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- Gladstein 1999, p. 118

- Woodward 1957, p. 25

- Hicks 1957, p. 5

- "Solid Gold Dollar Sign". Time. October 14, 1957. p. 128.

- Chambers 1957, p. 595

- Chambers 1957, p. 594

- Chambers 1957, p. 596

- McLaughlin 1958, pp. 144–146

- Chamberlain, John (October 6, 1957). "Ayn Rand's Political Parable and Thundering Melodrama". The New York Herald Tribune. p. 6.1.

- "Bible Ranks 1 of Books That Changed Lives". Los Angeles Times. December 2, 1991.

- Headlam, Bruce (July 30, 1998). "Forget Joyce; Bring on Ayn Rand". The New York Times (Late East Coast ed.). p. G4.

- Yardley, Jonathan (August 10, 1998). "The Voice of the People Speaks. Too Bad It Doesn't Have Much to Say". The Washington Post (Final ed.). p. D2 – via ProQuest.

- "100 Best Novels". Random House. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- "The Great American Read". PBS.

- Hospers, John (October 1977). "Atlas Shrugged: A Twentieth Anniversary Tribute". Libertarian Review. 6 (6): 41–43.

- "Prometheus Awards". Libertarian Futurist Society. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Hundreds Gather to Celebrate Atlas Shrugged". Cato Policy Report. November–December 1997. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- "Break Free! An Interview with Nathaniel Branden" (PDF). Reason. October 1971. p. 17.

- Branden 1984

- von Mises, Ludwig. Letter dated January 23, 2958. Quoted in Hülsmann, Jörg Guido (2007). Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism. Auburn, Alabama: The Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 996. ISBN 978-1-933550-18-3.

- Edwards, Lee (May 5, 2010). "First Principles Series Report #29 on Political Thought". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- "How About A Mini Atlas Shrugged? – Nealz Nuze On". Boortz.com. December 18, 2008. Archived from the original on February 5, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- Brook, Yaron (March 15, 2009). "Is Rand Relevant?". Wall Street Journal.

- Thomas 2007, pp. 62, 187

- Moore, Stephen (January 9, 2009). "Atlas Shrugged': From Fiction to Fact in 52 Years". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- Chait, Jonathan (December 28, 2010). "Paul Ryan And Ayn Rand". The New Republic. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Krugman, Paul (December 28, 2010). "Rule by the Ridiculous". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Costa, Robert (April 26, 2012). "Ryan Shrugged Representative Paul Ryan debunks an "urban legend"". The National Review. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- Krugman, Paul (August 9, 2013). "More on the Disappearance of Milton Friedman". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- Krugman, Paul (September 23, 2010). "I'm Ellsworth Toohey!". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- White, Robert (2010). "Endless Egoists: The Second-Hand Lives of Mad Men". In Carveth, Rod; South, James B. (eds.). Mad Men and Philosophy: Nothing Is as It Seems. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79–94. ISBN 978-0-470-60301-7. OCLC 471799585.

- Sciabarra 2004

- Perry, Douglass C. (May 26, 2006). "The Influence of Literature and Myth in Videogames". IGN. Retrieved October 7, 2007.

- Bodzin, Steven (March 2014). "Libertarians Plan to Sit Out the Coming Collapse of America...in Chile". Mother Jones.

- Hutchinson, Brian (September 26, 2014). "'Freedom and liberty' not enough to save Galt's Gulch, Chile libertarian community from bureaucracy and internal dissent". National Post.

- Cheadle, Harry (September 22, 2014). "Atlas Mugged: How a Libertarian Paradise in Chile Fell Apart". Vice. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- Morla, Rebeca (December 23, 2015). "Defrauded Investors File Lawsuit to Recover Galt's Gulch Chile". PanAm Post. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- Britting, Jeff. "Bringing Atlas Shrugged to Film". In Mayhew 2009, p. 195

- Brown 2007

- Carter 2014, pp. 75–77

- McClintock 2006

- Fleming 2007

- Fleming, Mike (May 26, 2010). "'Atlas Shrugged' Rights Holder Sets June Production Start Whether Or Not Stars Align". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- Murty, Govindini (July 21, 2010). "Exclusive: LFM Visits the Set of Atlas Shrugged + Director Paul Johansson's First Interview About the Film". Libertas Film Magazine. Archived from the original on August 1, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Kay, Jeremy (July 26, 2010). "Production Wraps on Atlas Shrugged Part One". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- Carter 2014, p. 89

- Carter 2014, p. 85

- "Atlas Shrugged Part I". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Weigel 2011

- Keegan 2011

- Carter 2014, pp. 90–91

- Key 2012

- DeSapio 2012

- Carter 2014, p. 91

- Carter 2014, p. 93

- Carter 2014, p. 92

- Carter 2014, p. 95

- Knegt 2013

- "Atlas Shrugged: Part II". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- Bond, Paul (March 26, 2014). "'Atlas Shrugged: Who Is John Galt?' Sets Sept. 12 Release Date (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- "Atlas Shrugged Part III: Who is John Galt?". Movie Mojo.

- "Atlas Shrugged: Who is John Galt?". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

Works cited

- Bradford, R. W. (May 1994). "Was Ayn Rand a Plagiarist?" (PDF). Liberty. Vol. 7 no. 4. pp. 56–58.

- Branden, Barbara (1986). The Passion of Ayn Rand. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 978-0-385-19171-5.

- Branden, Nathaniel (Fall 1984). "The Benefits and Hazards of the Philosophy of Ayn Rand: A Personal Statement". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 24 (4): 29–64. doi:10.1177/0022167884244004.

- Brown, Kimberly (January 14, 2007). "Ayn Rand No Longer Has Script Approval". New York Times. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- Burns, Jennifer (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7.

- Carter, Joan (2014). "The History of the Atlas Shrugged Movie Trilogy". In Kelley, David (ed.). Atlas Shrugged: The Novel, the Films, the Philosophy. The Atlas Society. ISBN 978-1-5010-5924-7.

- Chambers, Whittaker (December 8, 1957). "Big Sister is Watching You". National Review. pp. 594–596.

- DeSapio, Scott (April 2, 2012). "Atlas Shrugged Part 2 Begins Principal Photography". Atlas Shrugged Movie. Atlas Productions. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- Fleming, Michael (September 4, 2007). "Vadim Perelman to Direct 'Atlas'". Variety. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (1999). The New Ayn Rand Companion. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30321-0.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (2000). Atlas Shrugged: Manifesto of the Mind. Twayne's Masterwork Studies series. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-1638-2.

- Hansen, William (2004). Handbook of Classical Mythology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-226-4.

- Heller, Anne C. (2009). Ayn Rand and the World She Made. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51399-9.

- Hicks, Granville (October 13, 1957). "A Parable of Buried Talents". The New York Times Book Review. pp. 4–5.

- Hunt, Robert (1983). "Science Fiction for the Age of Inflation: Reading Atlas Shrugged in the 1980s". In Slusser, George E.; Rabkin, Eric S. & Scholes, Robert (eds.). Coordinates: Placing Science Fiction and Fantasy. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 80–98. ISBN 978-0-8093-1105-7.

- Keegan, Rebecca (April 26, 2011). "'Atlas Shrugged' Producer: 'Critics, You Won.' He's Going 'On Strike'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Kinsella, Stephan (October 2, 2007). "Ayn Rand and Garet Garrett". Mises Economics Blog. Ludwig von Mises Institute. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- Knegt, Peter (January 4, 2013). "The 5 Biggest Disappointments at the 2012 Specialty Box Office". IndieWire. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- Key, Peter (February 6, 2012). "Atlas Shrugged: Part 2 Movie Funded". Philadelphia Business Journal. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2009). Essays on Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2780-3.

- McClintock, Pamela (April 26, 2006). "Lionsgate Shrugging". Variety. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- McConnell, Scott (2010). 100 Voices: An Oral History of Ayn Rand. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-23130-7.

- McLaughlin, Richard (January 1958). "The Lady Has a Message ...". The American Mercury. pp. 144–146.

- Pierce, John J. (1989). When World Views Collide: A Study in Imagination and Evolution. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25457-4.

- Raimondo, Justin (2008) [1993]. Reclaiming the American Right: The Lost Legacy of the Conservative Movement. Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books. ISBN 978-1-933859-60-6.

- Ramsey, Bruce (December 27, 2008). "The Capitalist Fiction of Garet Garrett". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Rand, Ayn (1992) [1957]. Atlas Shrugged (35th anniversary ed.). New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94892-6.

- Rand, Ayn (1997). Harriman, David (ed.). Journals of Ayn Rand. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94370-9.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (March–April 1999). "Books for Rand Studies". Full Context. 11 (4): 9–11.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 2004). "The Illustrated Rand" (PDF). The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 1–20. JSTOR 41560268. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (2013). Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical (2nd ed.). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-06227-3.

- Thomas, Clarence (2007). My Grandfather's Son: A Memoir. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-056556-5.

- Walker, Jeff (1999). The Ayn Rand Cult. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 0-8126-9390-6.

- Weigel, David (March 3, 2011). "Libertarians Shrugged". Slate. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Woodward, Helen Beal (October 12, 1957). "Non-Stop Daydream". Saturday Review. p. 25.

- Younkins, Edward W., ed. (2007). Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged: A Philosophical and Literary Companion. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5533-6.

Further reading

- Branden, Nathaniel (1962). "The Moral Revolution in Atlas Shrugged". Who is Ayn Rand?. Book co-authored with Barbara Branden. New York: Random House. pp. 3–65. OCLC 313377536. Reprinted by The Objectivist Center as a booklet in 1999, ISBN 1-57724-033-2.

- Michalson, Karen (1999). "Who Is Dagny Taggart? The Epic Hero/ine in Disguise". In Gladstein, Mimi Reisel & Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (eds.). Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand. Re-reading the Canon. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-534-57625-7.

- Wilt, Judith (1999). "On Atlas Shrugged". In Gladstein, Mimi Reisel & Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (eds.). Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand. Re-reading the Canon. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-534-57625-7.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Atlas Shrugged |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Atlas Shrugged |

- Atlas Shrugged (Centennial Edition) at Google Books

- Atlas Shrugged on Goodreads

- Free Online CliffsNotes for Atlas Shrugged

- Website dedicated to Atlas Shrugged

- Timeline of major events in the novel

- Atlas Shrugged Essay Contest

- Atlas Shrugged study guide, themes, quotes, literary devices, teaching resources