Sunshine (1999 film)

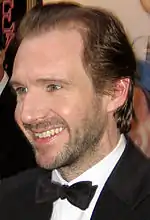

Sunshine is a 1999 historical drama film directed by István Szabó and written by Israel Horovitz and Szabó. It follows five generations of a Hungarian Jewish family, originally named Sonnenschein (German: "sunshine"), later changed to Sors (Hungarian: "fate"), during changes in Hungary, focusing mostly on the three generations from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century. The family story traverses the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through to the period after the 1956 Revolution, while the characters are forced to surrender much of their identity and endure family conflict. The central male protagonist of all three generations is portrayed by Ralph Fiennes. The film's stars include Rachel Weisz and John Neville, with the real-life daughter and mother team of Jennifer Ehle and Rosemary Harris playing the same character across a six-decade storyline.

| Sunshine | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | István Szabó |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

| Cinematography | Lajos Koltai |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 180 minutes[1] |

| Country |

|

| Language |

|

| Budget | $26 million |

| Box office | $7.6 million[3] |

The film was an international co-production among companies from Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Canada. It won three European Film Awards, including Best Actor for Fiennes, and three Canadian Genie Awards, including Best Motion Picture.

Plot

The mid-19th-century patriarch of the Hungarian-Jewish Sonnenschein ("Sunshine") family is a tavern owner who makes his own popular distilled herb-based tonic in Austria-Hungary. The tonic, called Taste of Sunshine, is later commercially made by his son, Emmanuel, bringing the family great wealth and prestige. He builds a large estate where his oldest son, Ignatz, falls in love with his first cousin, Valerie, despite the disapproval of Emmanuel and Rose. Ignatz, while studying in law school, begins an affair with Valerie. Ignatz graduates and later earns a place as a respected district judge, when he is asked by the chief judge to change his Jewish surname in order to be promoted to the central court. The entire generation – Ignatz, his physician brother Gustave and photographer cousin Valerie – change their last name to Sors ("fate"), a more Hungarian-sounding name. Ignatz then gets promoted when he tells the Minister of Justice a way to delay the prosecution of corrupt politicians.

In the spring of 1899, when Valerie becomes pregnant, she and Ignatz happily marry before the birth of their son, Istvan. Their second son, Adam, is born in 1902. Ignatz continues to support the Habsburg monarchy, while Gustave pushes for a communist revolution. Both brothers enlist in the Austro-Hungarian Army as officers during World War I. In the days after the war, Valerie briefly leaves him for another man, the old monarchy collapses, and Ignatz loses his judicial position under a series of short-lived socialist and communist regimes in which Gustave is involved. When a new monarchy emerges and asks Ignatz to oversee trials of retribution against the communists, he declines and is forced to retire. His health deteriorates rapidly and he dies, leaving Valerie as head of the family.

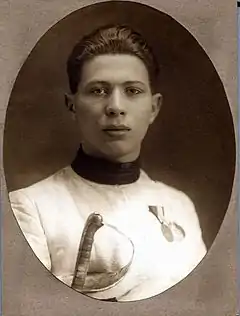

Istvan and Adam both join the Jewish-run Civic Fencing Club. Adam becomes the best fencer in Hungary, and General Jakofalvy invites him to convert to Roman Catholicism in order to join the nation's top military, non-Jewish, fencing club. While Adam and Istvan are converting, Adam meets Hannah, who is converting at the request of her fiancé, and woos her into marrying him. Adam wins the national fencing championship two years in a row and goes on to lead the national team to the 1936 Olympic gold medal in Team Sabre in Nazi Germany, becoming a national hero in Hungary. Istvan's wife, Greta, pursues Adam until they start a secret affair.

New Hungarian laws are passed discriminating against people with any near Jewish ancestors, and the Sors family is initially shielded by the exceptions in the laws. However, Adam is soon expelled from the military fencing club. Greta finally convinces the family that they must emigrate to save their children, but they are too late to get exit visas.

When Germany occupies Hungary, Valerie and Hannah are immediately moved into the Budapest Ghetto. Hannah escapes and hides in a friend's attic, but is later betrayed; nobody knows how or where she died. Adam and his son Ivan are sent to a labor camp, where Adam is beaten, stripped naked and hosed with water until he freezes to death. Istvan, Greta and their son are summarily shot by Nazis.

After the war, the surviving Sors family returns to the Sonnenschein estate. The elderly Gustave returns from exile and is invited into the communist government, Valerie manages the household, and Ivan becomes a state policeman, working for police Major General Knorr rounding up fascists from the wartime regime. Ivan rises quickly in the communist ranks and begins an affair with Carole, the wife of a high-ranking communist official. Later, Army General Kope asks Ivan to start vigorously arresting Jews, including Knorr, who are suspected of inciting conspiracies against the current government. After Gustave dies, Kope informs Ivan that his uncle would have been next to be investigated.

When Stalin dies in 1953, Ivan feels guilty for helping Kope and not saving Knorr. He leaves the police force and swears to fight the communist regime. In the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, he steps up as a leader, but is imprisoned after it fails. Released at the end of the decade, he returns to live together with Valerie in a single room of the former family estate. She falls ill while they search for the tonic recipe—after she dies, he fruitlessly continues the search. Ivan changes his name from Sors back to Sonnenschein, and concludes his storytelling after the end of the communist regime in 1989.

Cast

- Ralph Fiennes as Ignatz Sonnenschein (Sors) / Adam Sors / Ivan Sors

- Rosemary Harris as senior Valerie Sors

- Rachel Weisz as Greta Sors

- Jennifer Ehle as younger Valerie Sonnenschein (Sors)

- Deborah Kara Unger as Maj. Carole Kovács

- Molly Parker as Hannah Wippler (Sors)

- James Frain as younger Gustave Sonnenschein (Sors)

- David de Keyser as Emanuel Sonnenschein

- John Neville as senior Gustave Sors

- Miriam Margolyes as Rose Sonnenschein

- Rudiger Vogler as General Jakofalvy

- Mark Strong as István Sors

- Bill Paterson as Minister of Justice

- Trevor Peacock as Comrade Gen. Kope

- William Hurt as Andor Knorr

- Mari Törőcsik as Older Kató

- Péter Halász as Wild Duck

- Péter Andorai as Anselmi

- Flóra Kádár as Mrs. Hackl

- Sándor Simó as Doctor

- Zoltán Gera as Man at Synagogue

- András Stohl as Red Guard

- Gábor Mádi Szabó as Priest at Conversion

- László Gálffi as Rossa

- Eszter Ónodi as Secretary at Officer's Club

- Ádám Rajhona as Caretaker

- János Kulka as Molnár

- Lajos Kovács as MP in Camp

- Gábor Máté as Rosner

- György Kézdy as Outraged Man

- Frigyes Hollósi as Mr. Ledniczky

Themes

Psychologist Diana Diamond identified themes in the film as "Trauma, familial and historical", and how it has lasting effects on the individual's psychology.[4] The character Ivan's status as narrator reflects this theme, as he witnesses Adam's death in the concentration camp.[5] In exploring the relationship between Ignatz, Valerie and their brother Gustave and alleged adultery, the film portrays "Oedipal rivalries" and incest.[6] The film also addresses the question of identity. Vladimir Tumanov, Professor of Literature and the Bible, wrote that, while brewer Emmanuel Sonnenschein does not completely reject either his Jewish heritage or Hungarian life, his descendants falter on this compromise, with Ignatz abandoning the name Sonnenschein and becoming fiercely loyal to Emperor Franz Joseph.[7] Each generation goes ever further in repeating this pattern of moving into positions of "gentile power" by denying their Jewish name and religion and peoples, only to be attacked and even killed for being Jews, while also repeating a pattern of "the dysfunctional sexual life of the Sonnenschein" generations.[7] Author Christian Schmitt adds Sunshine may also strive to add a message of hope to the tragedies of history.[8]

Professor Dragon Zoltan writes the film starts by contrasting the title Sunshine with clouds as a backdrop, to communicate a force standing in the way of the sunshine.[9] He argues the name of the family's brand, Taste of Sunshine, which is also the literal translation of the film's Hungarian title, suggests that the family's happiness stays with those who have tasted it, even after it is finished.[10] The name Sonnenschein is also said in the film to underline the family's Jewish background, while Sors (fate) maintains the first two letters while erasing the Jewish traces.[11] Ivan becomes a Sonnenschein again after reading a letter telling him how to live, representing the lost recipe of the family brand.[12]

Production

Development

Although the story is a work of fiction, the film draws inspiration from historic events. The Sonnenschein family's liquor business was based on the Zwack family's liquor brand Unicum.[13] One of Fiennes's three roles is based at least partly on Hungarian Olympian Attila Petschauer.[14] Another role in the film which is similar to that of a historic person is the character Andor Knorr, played by William Hurt, which closely resembles the latter part of the life of László Rajk.[15] Sonnenschein itself was a name in director István Szabó's family.[16]

Hungarian-born Canadian producer Robert Lantos aspired to help make a film reflecting his family background of Hungarian Jews. Sunshine was his first project after leaving the position of CEO in Alliance Films.[16]

Szabó shared his idea for the story with Lantos, a friend, in a restaurant, and Lantos was interested. Szabó submitted a screenplay of 400 pages in Hungarian, with Lantos persuading him to condense it and translate to English.[16] The budget was $26 million.[17]

Filming

Shooting took place mainly in Budapest.[19] The Berlin Olympics scene was shot in Budapest and required 1,000 extras.[16] The exterior of the Budapest estate of the Sonnenschein family, with a large mansion and distillery, was filmed at an apartment building at 15 Bokréta Street (Bokréta utca 15), in the city's central Ferencváros district.[18] The filmmakers painted a sign near the top of the building's façade to identify it, for purposes of the story, as belonging to "Emmanuel Sonnenschein & tsa. Liquer" (where tsa. translates to co., for Company).[18] In July 2008, director Szabó and cinematographer Koltai were on hand as invited guests for the grand re-opening of the apartment complex, as the municipal and district governments chose to maintain the fictional company name on the façade and officially name it The Sonnenschein House, after the governments spent 300 million forints renovating the building.[20][21] Interior shots of the family mansion were filmed at a nearby building, on Liliom Street.[20]

Fiennes described Szabó as very specific in how scenes were staged and how performances were given. On some shooting days, Fiennes would play all three of his characters, particularly if a specific location was only available for a limited time.[22]

Release

The film premiered in the Toronto International Film Festival in September 1999.[23] Alliance Atlantis distributed the film in Canada.[24] It opened in Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal from December 17 to 19, 1999.[25]

This was followed by a release in Munich and Budapest in mid-January 2000, with a wider release in Germany, Austria and Hungary later that month.[17] In February 2000, it was showcased in the 31st Hungarian Film Week, held in Budapest, where it won the Gene Moskowitz Best Film award.[26] After U.S. screenings in summer 2000, Paramount Classics re-released it in New York City and Los Angeles on 1 December to promote Sunshine for the Academy Awards.[27]

Reception

Box office

On the opening weekend in the Canadian limited release, the film made $42,700.[25] In its first 19 days, the film grossed $300,000 in Canada, with expectations that if the film made a profit, it would be due to international screenings, TV rights and VHS and DVD.[17]

By 25 November 2000, it had made $1 million in Canadian theatres.[27] The film finished its run after grossing $5,096,267 in North America. It made $2,511,593 in other territories, for a worldwide total of $7,607,860.[3]

Critical reception

Sunshine has a 73% approval rating and average rating of 7.1 out of 10, based on 64 reviews, on Rotten Tomatoes.[28] Roger Ebert gave Sunshine three stars, calling it "a movie of substance and thrilling historical sweep".[23] In Time, Richard Schickel remarked on the irony of the title in a film that conveyed how history devastates people.[29] National Review's John Simon praised Szabó's direction, Lajos Koltai's cinematography and especially the performances of Ralph Fiennes and the supporting cast.[30] In The New Republic, Stanley Kauffmann compared Szabó favorably to David Lean in a cinematic treatment of history, and despite the long runtime, "Sunshine is so sumptuous, the actors so refresh the very idea of good acting, that we are left grateful".[31]

In The New York Times, A.O. Scott assessed the film as occasionally awkward, but wrote it made the viewer think.[32] Michael Wilmington of The Chicago Tribune gave the film three and a half stars, praising it for its aesthetic photography and defending Fiennes for "deep understanding, burning intensity and rich contrast".[33] Mick LaSalle called Sunshine "glorious", Fiennes "superb", and also praised Weisz, Ehle and Hurt.[34] Time later placed it in its top 10 films of 2000.[35]

Eddie Cockrell criticized the film in Variety for a "general rushed feel of the proceedings" in covering a great deal of history.[36] The Guardian critic Andrew Pulver wrote Sunshine depended on Fiennes, who "only partly succeeds", negatively reviewing Fiennes' performances as Ignatz and Ivan.[37]

Accolades

Sunshine received 14 nominations at the 20th Genie Awards, following the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television's decision to revise rules allowing films with only a minority of Canadian involvement in production to compete, with also allowed Felicia's Journey to be nominated for 10.[38]

References

- "SUNSHINE (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 10 December 1999. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- Vidal 2012, p. 130.

- "Sunshine (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Diamond 2005, p. 101.

- Diamond 2005, p. 109.

- Diamond 2005, p. 104.

- Tumanov, Vladimir (October 2004). "Daniel and The Sonnenscheins: Biblical Cycles in István Szabó's Film Sunshine". The Journal of Religion and Film. 8 (2). Archived from the original on 12 December 2004.

- Schmitt 2013, p. 195.

- Zoltan 2009, p. 74.

- Zoltan 2009, p. 75.

- Zoltan 2009, p. 76.

- Zoltan 2009, p. 78.

- Portuges 2016, p. 127.

- Soros 2001, p. 234.

- Reeves 2011.

- Johnson, Brian D. (2 November 1998). "Hungarian rhapsody". Maclean's. Vol. 111 no. 44.

- Playback Staff (24 January 2000). "Sunshine rising in Europe". Playback. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Csákvári, Gáza; Csordás, Lajos (29 October 2008). "Sonnenschein House, Rocky Statue". Népszabadság. Mediaworks Hungary. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- N.A. (22 December 2000). "Golden opportunity". The Toronto Star. p. MO20.

- "Sonnenschein House Renovation Complete". Index.hu. 24 July 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Google street view, as of September 2017, still shows film markings "EMMANUEL SONNENSCHEIN & tsa. ("Company") LIQUEUR"

- Fiennes, Ralph; Rose, Charlie (28 December 2000). "Ralph Fiennes". Charlie Rose. PBS.

- Ebert, Roger (23 June 2000). "Sunshine". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- MacDonald, Fiona (17 December 1999). "Sunshine tells Hungarian tale". Playback. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Playback Staff (10 January 2000). "Sunshine tops $300K, Laura $1M". Playback. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Nadler, John (14 February 2000). "Hungary Trips in Time". Variety. Vol. 377 no. 13. p. 25.

- N.A. (25 November 2000). "The `s-'ence of Canadian super-producer Robert Lantos". The Toronto Star. p. AR17.

- "SUNSHINE 2000". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- Schickel, Richard (12 June 2000). "Sun Sage". Time. Vol. 155 no. 24. p. 82.

- Simon, John (3 July 2000). "More Clouds Than Sun". National Review. p. 52.

- Kauffmann, Stanley (12 June 2000). "Some History, Some Hysterics". The New Republic. Vol. 222 no. 24. pp. 32–34.

- Scott, A.O. (9 June 2000). "FILM REVIEW; Serving the Empire, One After Another After . . ". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Wilmington, Michael (23 June 2000). "Fiennes Shines In Deeply Personal Epic 'Sunshine'". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- La Salle, Mick (23 June 2000). "`Sunshine' Shines Through / Fiennes well-supported in beautiful, original epic". SF Gate. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- N.A. (22 December 2000). "Golden opportunity". The Toronto Star. p. MO20.

- Cockrell, Eddie (15 September 1999). "Sunshine". Variety. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- Pulver, Andrew (28 April 2000). "Sunshine". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- Kelly, Brendan (13 December 1999). "Genies bottle `Sunshine,' `Journey' for kudo noms". Variety. Vol. 377 no. 5. p. 8.

- "1999: The Nominations". European Film Academy. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "1999: The Winners". European Film Academy. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- "Sunshine, Felicia's Journey top Genie Awards". CBC News. 31 January 2000. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- "Sunshine". Golden Globes. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- "2000 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- MH (1 July 2000). "Sunshine". Political Film Society. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Reifsteck, Greg (18 December 2000). "'Gladiator,' 'Traffic' lead Golden Sat noms". Variety. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- MacDonald, Fiona (17 April 2000). "WGC Awards: TV is 'bread & butter'". Playback. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Diamond, Diana (5 July 2005). "István Szabó's Sunshine". The Couch and the Silver Screen: Psychoanalytic Reflections on European Cinema. London: Routledge. ISBN 1135444528.

- Portuges, Catherine (2016). "Traumatic Memory, Jewish Identity: Remapping the Past in Hungarian Cinema". East European Cinemas. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 1135872643.

- Reeves, T Zane (2011). "XXVI: I'll Be a Tree". Shoes Along the Danube: Based on a True Story. Strategic Book Publishing. ISBN 1618972758.

- Schmitt, Christian (23 May 2013). "Beyond the Surface, Beneath the Skin". Iconic Turns: Nation and Religion in Eastern European Cinema since 1989. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9004250816.

- Soros, Tivadar (2001). Masquerade: Dancing Around Death in Nazi-occupied Hungary. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1559705817.

- Vidal, Belen (3 April 2012). Heritage Film: Nation, Genre, and Representation. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231850042.

- Zoltan, Dragon (27 May 2009). The Spectral Body: Aspects of the Cinematic Oeuvre of István Szabó. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 1443811440.

External links

- Sunshine at IMDb

- Sunshine at Rotten Tomatoes

- A napfény íze at PORT.hu (in Hungarian)