Subtropical Storm Andrea (2007)

Subtropical Storm Andrea was the first named storm to form in May in the Atlantic Ocean in 26 years. Andrea caused large waves and tropical-storm force winds along the southeast coast of the United States. The first named storm and the first subtropical cyclone of the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season. Andrea developed out of a non-tropical low on May 9 about 150 miles (240 km) northeast of Daytona Beach, Florida, three weeks before the official start of the season. After encountering dry air and strong vertical wind shear, Andrea weakened to a subtropical depression on May 10 while remaining nearly stationary, and the National Hurricane Center discontinued advisories early on May 11. Andrea's remnant was subsequently absorbed into another extratropical storm on May 14. Andrea was the first pre-season storm to develop since Tropical Storm Ana in April 2003. Additionally, the storm was the first Atlantic named storm in May since Tropical Storm Arlene in 1981.[1]

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

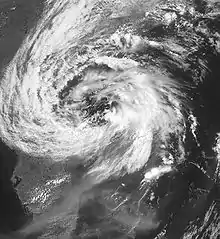

.JPG.webp) Andrea shortly before being classified as a subtropical storm, on May 8 | |

| Formed | May 9, 2007 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | May 14, 2007 |

| (Extratropical after May 11) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 60 mph (95 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 1001 mbar (hPa); 29.56 inHg |

| Fatalities | 6 indirect |

| Damage | Minimal |

| Areas affected | Virginia, Southeastern U.S., Bahamas |

| Part of the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The storm produced rough surf along the coastline from Florida to North Carolina, causing beach erosion and some damage. In some areas, the waves eroded up to 20 feet (6 m) of beach, leaving 70 homes in danger of collapse. Offshore North Carolina, high waves of 34 feet (10 m) and tropical-storm-force winds damaged three boats; their combined nine passengers were rescued by the Coast Guard, although all nine sustained injuries. Light rainfall was also reported in some coastal locations. Damage was minimal, but six people drowned as a result of the storm.

Meteorological history

In early May, an upper-level trough dropped southward through the western Atlantic Ocean, forcing a back-door cold front—a cold front that moves southwestward ahead of a building surface ridge to its north or northeast—southward. For several days, forecast models had anticipated for the trough to evolve into a closed low pressure area,[2] and on May 6, a frontal low with a large and well-defined circulation developed about 90 miles (140 km) east of Cape Hatteras. The low maintained scattered convection around its circulation center, and in conjunction with the strong high pressure to its north, a very tight pressure gradient produced gale-force winds near the coastline.[3] The extratropical storm tracked southeastward and later turned to the southwest while steadily deepening; on May 7, it attained hurricane-force winds.[4] With a lack of tropical moisture, its corresponding convection was minimal and scattered.[5]

The National Hurricane Center first mentioned the possibility of tropical cyclogenesis on May 8, while the storm was located about 230 miles (370 km) east-southeast of the South Carolina coastline. Its associated convection had steadily increased as it tracked slowly westward at 5–10 mph (8–16 km/h).[6] The system changed little in organization throughout the day,[7] though by the following morning, hurricane specialists indicated the low was acquiring subtropical characteristics[8] as it tracked over progressively warmer waters.[4] Early on May 9, a Hurricane Hunters flight into the system revealed winds of 45 mph (70 km/h) and a flat thermal core, which indicated the system was neither warm-core nor cold-core. In addition, satellite imagery indicated a consolidation of the convection near the center, as well as hints of upper-level outflow and a contraction of the radius of maximum winds from more than 115 miles (185 km) to about 70 miles (120 km). Based on the observations and the hybrid structure of the system, the National Hurricane Center classified the low as Subtropical Storm Andrea at 1500 UTC on May 9 about 150 miles (240 km) northeast of Daytona Beach, Florida.[9] During a subsequent analysis of the storm, researchers estimated that the storm had transitioned into a subtropical cyclone nine hours earlier.[4] As Andrea developed before June 1—the traditional start of hurricane seasons in the Atlantic Ocean—it became the first pre-season storm since Tropical Storm Ana in April 2003. Additionally, the storm was the first Atlantic named storm in May since Tropical Storm Arlene in 1981.[1]

Upon first becoming a subtropical cyclone, Andrea was embedded within a large, nearly stationary deep-layer trough, resulting in a westward movement. Drifting over sea surface temperatures of no more than 77 ° F (25 °C),[9] the organization of the system deteriorated with a significant decrease in convection.[10] By early on May 10, much of the associated weather was located to the east of the cyclone within a band of moderate convection due to a brief spell of westerly vertical wind shear. The center of circulation had become disorganized, with several small cloud swirls within the larger circulation.[11] This disorganization of the center, combined with increasing wind shear and dry air suppressing convective activity, caused it to begin weakening later that morning.[12] By 1500 UTC on May 10, only a few thunderstorms remained near the center, and thus the NHC downgraded Andrea to subtropical depression status.[13] Though a few intermittent thunderstorms persisted over the eastern semicircle, the depression remained disorganized and weak; the National Hurricane Center discontinued advisories early on May 11, after it had been without significant deep convection for 18 hours about 80 miles (125 km) northeast of Cape Canaveral, Florida.[14]

Later on May 11, convection re-fired over the center as the system drifted south-southeastward, though it lacked sufficient organization to qualify as a tropical cyclone.[15] By May 12, shower activity had organized greatly to the east of the center, and the National Hurricane Center remarked that a small increase in convection would result in the formation of a tropical depression.[16] It accelerated east-northeastward away from the continental United States without redeveloping, and after passing over cooler waters,[17] the remnants of Andrea merged with an approaching cold front on May 14.[18]

Preparations

Due to rough surf from the precursor low, local National Weather Service offices issued a High Surf Advisory for much of the coastline from Florida through North Carolina.[3] Upon first becoming a subtropical cyclone, the National Hurricane Center issued a tropical storm watch from the mouth of the Altamaha River in Georgia southward to Flagler Beach, Florida.[19] The watch was discontinued after Andrea weakened to a subtropical depression.[13] Additionally, a gale warning was issued for much of the South Carolina coastline.[20]

At Isle of Palms in South Carolina, workers and dozens of firefighters prepared sandbags in preparation for high tide after waves from the storm previously caused moderate beach erosion. As a precaution, officials there intentionally cut power and gas to multiple uninhabited buildings.[20] Officials closed schools in Dare County, North Carolina due to the threat for high winds from the storm. The North Carolina Department of Transportation also canceled ferry transportation to and from Ocracoke and Knotts Island, North Carolina.[21]

Impact

Prior to becoming a subtropical cyclone, the low produced gale-force winds and dangerous surf near the coast from North Carolina through Georgia,[6] and later along the coast of Florida.[7] Significant swells were also reported in the Bahamas.[22] The waves caused beach erosion and washed up against coastal houses along the southeast coast of the United States.[23]

Southeastern U.S.

Off the coast of North Carolina, the storm produced 34-foot (10-m) waves and storm force winds which damaged three boats; their combined nine passengers were rescued by the Coast Guard. All nine were injured to some degree; three endured hypothermia, one received a broken rib, and one Coast Guardsman experienced back injuries from the surf.[24] Another boat and its four occupants were reported missing,[21][25] and after twelve days they remain missing.[26] Rough waves from the precursor low left two kayakers missing near Seabrook Island, South Carolina. One was found the next day,[27] and the other was found dead a week later.[28]

Onshore, winds reached 52 mph (84 km/h) in Norfolk, Virginia, with an unofficial report of 57 mph (92 km/h) near Virginia Beach. Similar observations occurred along the Outer Banks,[29] with the winds knocking some tree limbs onto power lines;[30] some isolated power outages were reported.[21] Wind damage included some roofs losing shingles from the winds.[29] In Elizabeth City, North Carolina, an outer rainband dropped 0.5 inches (10 mm) of precipitation in about two hours as well as several lightning strikes; one bolt of lightning injured two firefighters.[21] The winds covered portions of North Carolina Highway 12 with sand,[29] and for a day the route was closed after waves from the storm washed out about 200 feet (60 m) of roadway.[21] In some locations, the waves eroded up to 20 feet (6 m) of beach, leaving 70 homes in imminent danger.[31] On St. Simons Island in Georgia, the storm produced a storm tide of 8.09 feet (2.43 m). Trace amounts of rainfall occurred in the southeastern portion of the state.[32]

Florida

In Florida, waves of over 10 feet (3 m) in height capsized a boat near Lantana; the two occupants were rescued without injury. Additionally, the waves displaced a sailboat that had previously been washed ashore in Juno Beach. Large waves flooded a parking lot and destroyed several fences and tree branches at Jupiter Beach, which resulted in its temporary closure; nearby a maintenance shed was destroyed. Eight leatherback sea turtle nests in Boca Raton were destroyed after the surf reached the dunes.[33] Due to high surf, the beach pier at Flagler Beach was closed for about a day. Minor to moderate beach erosion caused the Florida Department of Transportation to fill in areas near the seawall with sand.[32] One death occurred when a surfer drowned in the rough waves off the coast at New Smyrna Beach in Volusia County.[34] Outer rainbands produced light rainfall, with the highest report in the Jacksonville National Weather Service area of responsibility totaling 0.77 inches (20 mm); the bands also caused tropical storm force wind gusts in the northeastern portion of the state.[32] The winds spread smoke from local brush fires through the Tampa Bay area to Miami.[35][36] High winds from Andrea were reported as fueling severe wildfires in northern Florida and southern Georgia.[37]

See also

References

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Cangialosi (2007). "May 4 Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2017-05-07. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Cangialosi (2007). "May 6 Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Jamie R. Rhome; Jack Beven & Mark Willis (2007). "Subtropical Storm Andrea Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- Cangialosi (2007). "May 7 Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Knabb (2007). "May 8 Special Tropical Disturbance Statement". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Brown (2007). "May 9 Special Tropical Disturbance Statement". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Franklin/Knabb (2007). "May 9 Special Tropical Disturbance Statement (2)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Knabb (2007). "Subtropical Storm Andrea Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Knabb (2007). "Subtropical Storm Andrea Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Avila (2007). "Subtropical Storm Andrea Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Mainelli (2007). "Subtropical Storm Andrea Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Knabb (2007). "Subtropical Depression Andrea Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Rhome (2007). "Subtropical Depression Andrea Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Knabb (2007). "May 11 Special Tropical Disturbance Statement". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- Franklin (2007). "May 12 Special Tropical Disturbance Statement". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- Beven (2007). "May 13 Special Tropical Disturbance Statement". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- National Hurricane Center. "June 1 Tropical Weather Outlook". Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- Knabb (2007). "Subtropical Storm Andrea Public Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Jennifer Wilson (2007). "Forecasters: Subtropical Storm Andrea has formed". WIStv Columbia, South Carolina. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Lauren King & Kristin Davis (2007-05-10). "Season's first named storm unleashes band of rain". Virginian Pilot. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Willis (2007). "May 8 Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Jessica Gresko (2007). "Year's first named storm becomes Andrea, forms 3 weeks before hurricane season begins". Associated Press.

- "High drama on high seas". Virginian Pilot. 2007-05-08.

- "Coast Guard continues search for missing sailors". Sunbeam Television. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-05-13. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Amanda Milkovits (2007). "Sailors' circle holds hope". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- "First named '07 Atlantic storm forms near coast". Associated Press. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- "DNA identifies missing Atlanta kayaker's body in S.C." Associated Press. 2007-05-24. Archived from the original on 2014-05-23. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- Steve Stone (2007-05-07). "Wind and chill chase away spring today's weather". Virginian Pilot. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Francine Sawyer (2007). "Storm moving away from coast". New Bern Sun Journal. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Bryan Mims (2007). "Offshore Storm System Raked N.C. Beaches". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Keegan, Shashy, McAllister, & Enyedi (2007). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Report". Jacksonville, Florida National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 2007-05-20. Retrieved 2007-05-19.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Erika Pesantes, Sally Apgar & Chrystian Tejedor (2007-05-09). "Sweeping erosion hits Palm Beach County coast: Low-pressure system sucks swaths of sand; Jupiter feels brunt of it". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Tanya Caldwell (2007). "Holly Hill surfer drowns after taking on 'gigantic wave' in New Smyrna Beach". Orlando Sentinel.

- "Subtropical storm Andrea is swirling off the north Florida coastline". Bradenton Herald. 2007.

- "Atlantic's first named storm whips up wildfires". CNN. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Kevin Spear & Jim Stratton (2007-05-12). "'Fire of a lifetime' hits North Florida". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Subtropical Storm Andrea (2007). |

| Wikinews has related news: |