1933 Atlantic hurricane season

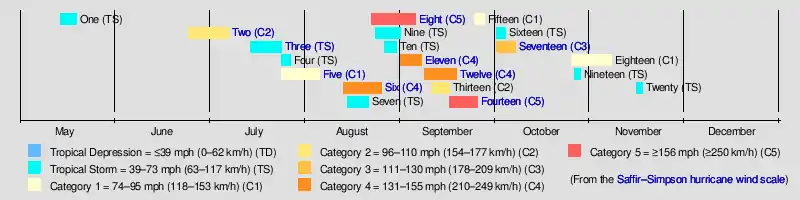

The 1933 Atlantic hurricane season set the pre-weather satellite record for most tropical storms formed within a single season, and currently ranks as the third-most active Atlantic hurricane season, only behind 2005 and 2020. It also produced the highest Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) on record in the Atlantic basin, with a total of 259.[1] The season ran through the summer and the first half of fall in 1933, with activity as early as May and as late as November. A tropical cyclone was active for all but 13 days from June 28 to October 7.

| 1933 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 14, 1933 |

| Last system dissipated | November 17, 1933 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Tampico" |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 929 mbar (hPa; 27.43 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 20 |

| Hurricanes | 11 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 6 |

| Total fatalities | 651 |

| Total damage | $86.6 million (1933 USD) |

| Related article | |

Because technologies such as Earth observation satellites were not available until the 1960s, historical data on tropical cyclones from the early 20th century is often incomplete. Tropical cyclones that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected.[2] Compensating for the lack of comprehensive observation and the limited technological ability to monitor all tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic Basin during this era, research meteorologist Christopher Landsea estimates that the 1933 season may have produced an additional 2–3 missed tropical cyclones.[2] A 2013 reanalysis of the 1933 Atlantic Hurricane Database did indeed identify two new tropical storms; however, it was also determined that two existing cyclones did not reach tropical storm intensity and so were removed from the database. Additionally, researchers found two existing storms to be one continuous system. As a result, the season storm total dropped from 21 to 20.[3]

Of the season's 20 documented tropical storms, 11 attained hurricane status. Six of those were major hurricanes, with sustained winds of over 111 mph (179 km/h). Two of the hurricanes reached winds of 160 mph (260 km/h), which is a Category 5–the highest of 5– on the modern Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[nb 1] The season produced several deadly storms, with eight storms killing more than 20 people. All but 3 of the 20 known storms affected land at some point during their durations.

Season summary

| Rank | Season | ACE |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1933 | 259 |

| 2 | 2005 | 250 |

| 3 | 1893 | 231 |

| 4 | 1926 | 230 |

| 5 | 1995 | 228 |

| 6 | 2004 | 227 |

| 7 | 2017 | 225 |

| 8 | 1950 | 211 |

| 9 | 1961 | 189 |

| 10 | 1998 | 182 |

The 1933 season was the most active of its time, surpassing the previous record-holder of 19 storms in 1887. Fifteen of the season's storms made landfall as tropical cyclones, and another struck land as extratropical storms. Eight tropical storms, including six hurricanes, hit the United States during the season, including the Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane, which the U.S. Weather Bureau described as one of the most severe in history to impact the Mid-Atlantic States. Seven tropical storms, including four hurricanes, hit Mexico, two of which caused severe damage in the Tampico area.[8]

The season was continuously active, with six storms forming during the month of August alone.[9] At the time, many storms received the distinction of being the earliest nth storm to form, such as the earliest fifth tropical storm to form in a season. Most of the records were broken in later years.[10] During the season, the U.S. Weather Bureau issued storm and hurricane warnings for eight storms, including coastal portions of Texas, as well as from Florida to Massachusetts, forcing the evacuations of thousands of people. The deadliest storm of the season was a hurricane that struck Tampico, Mexico, killing over 184 residents. The costliest hurricane was the Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane, which caused $27 million in damage from North Carolina to New Jersey.[nb 3] The hurricane produced rainfall that resulted in severe crop damage in Maryland.[8]

In addition to the 20 tropical storms, there were several tropical depressions of lesser intensity. The first developed on June 1 in the northwest Caribbean and dissipated a few days later. Another depression developed on July 11 over Panama and also quickly dissipated. A tropical depression developed on July 17 in the northeastern Atlantic west of the Azores, and one ship reported hurricane-force winds; however, there was little evidence that the tropical system was organized, so it was not classified as a tropical storm. Originally, there was a tropical storm in the database in the Caribbean in the middle of August, but it was downgraded to a tropical depression due to lack of any reports of gale-force winds. Similarly, there was a tropical storm in the database in late September, but it was also downgraded to a tropical depression due to lack of gale-force winds.[9]

The season produced the highest Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) on record, with a total of 259.[1] The measurement is a method to compare tropical cyclone activity between seasons. Originally, 1933 had an operational ACE of 213,[11] which was surpassed by 1950, 1995, 2004, 2005, and 2017.[12] However, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project found that the storms in 1933 were stronger than initially reported.[11]

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 14 – May 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) |

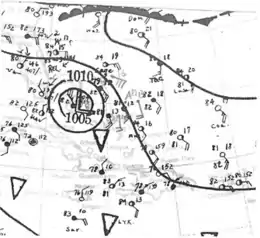

The first storm of the season formed on May 14 in the southwestern Caribbean Sea off the east coast of Nicaragua. It moved quickly to the north-northwest, passing just northeast of the eastern tip of Honduras. On May 15, the storm turned to the west and entered the Gulf of Mexico while moving around the Yucatán Peninsula. The next day, it attained peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h), based on a ship report. Turning southward, the storm made landfall on Ciudad del Carmen in Mexico early on May 19 with winds of 40 mph (64 km/h). It dissipated over land later that day.[9]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 24 – July 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 965 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave spawned a tropical depression on June 24 about halfway between the southern Lesser Antilles and the coast of Africa. The depression quickly intensified into a tropical storm, and by June 27 it became a hurricane off the northern coast of Guyana. At 2100 UTC that day, the hurricane struck extreme southern Trinidad with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h). After crossing the island, the hurricane moved across the Paria Peninsula in northeastern Venezuela with the same intensity.[9] The hurricane was earliest to affect the region on record, and was the first storm in over 50 years to affected Trinidad and Venezuela. In Trinidad, 13 people were killed, about 1,000 people were left homeless, and damage was estimated at $3 million. In Venezuela, the hurricane caused power outages, destroyed several houses, and killed several people.[8]

After crossing Venezuela into the eastern Caribbean, the hurricane moved northwestward and gradually intensified. On July 3 it struck western Cuba with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[9] In the country, the storm killed 22 people, while damage amounted to $4 million.[13] A building high pressure area turned the hurricane westward in the Gulf of Mexico,[8] and after further strengthening the storm attained peak winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) on July 5. It turned to the west-southwest and made landfall in northeastern Mexico on July 7 with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), about halfway between Tampico and the Mexico/United States border. It dissipated about 11 hours later over Mexico.[9] There were several deaths and heavy damage in the area where the storm moved ashore.[8] Across its path, the hurricane killed 35 people.[14]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 14 – July 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical storm of the season (initially classified as two separate storms but later identified as a single track) was first observed on July 14 near St. Kitts. It moved quickly westward and passed just south of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola as a weak storm. The system curved slightly to the west-northwest and brushed the northern coast of Jamaica before turning slightly westward and hitting the Mexican state of Quintana Roo. As it crossed the Yucatán Peninsula the cyclone weakened and eventually crossed into the Bay of Campeche. It moved quickly to the northwest, and made landfall near Matagorda Bay, in Texas on July 23 as a 45 mph (70 km/h) tropical storm. The system turned to the northeast, and became extratropical to the east of Dallas, Texas. The extratropical system moved slowly through northern Louisiana, turned to the northeast, and dissipated over northeastern Arkansas near Memphis, Tennessee.[8][15]

While passing near Jamaica, the storm dropped heavy rainfall, including 9 inches (230 mm) in Kingston which led to flooding and washouts. The rainfall also damaged several bridges and roads and resulting in delays in train schedules.[16] Mudslides and overflowing rivers flooded several towns with knee-deep waters. Moderate winds downed several banana trees across the island.[17] Prior to the arrival of the storm in Texas, numerous coastal residents boarded up their houses and businesses and voluntarily evacuated further inland. Upon making landfall, the storm produced high tides.[18] In eastern Texas and western Louisiana, the system dropped very heavy precipitation, which in places reached accumulations exceeding 20 inches (500 mm). The highest storm total occurred in Logansport, Louisiana, which reported 21.30 inches (541 mm) in a 4-day period.[19] In Louisiana, the flooding severely damaged crops and forced about 250 families near Shreveport to evacuate their flooded homes. The torrential rainfall also resulted in overflowing rivers; numerous highways, roads, and railroads were either impassable or closed, with some locations experiencing water depths of up to 20 feet (6.1 m).[20] Total damage reached nearly $2 million.[21]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 24 – July 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) |

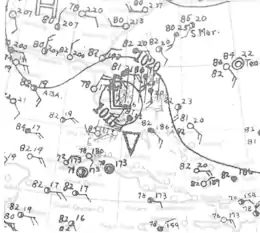

A dissipating cold front spawned a tropical depression east of Bermuda on July 24. It moved east-northeastward initially, and intensified into a tropical storm early on July 25. Based on ship observations, it is estimated the storm attained peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). The storm turned to the northeast and was absorbed by a cold front southeast of Newfoundland early on July 27.[9]

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 24 – August 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 975 mbar (hPa) |

On July 24, a tropical storm was detected. Located to the southeast of Antigua, it tracked west-northwestward, passing near St. Thomas with winds of up to 60 mph (95 km/h). The storm strengthened and attained hurricane status the next day north of Puerto Rico, and it continued its west-northwest movement. After moving through the northern Bahamas, the hurricane struck near Fort Pierce, Florida, with winds of 85 mph (135 km/h). The hurricane crossed the state and weakened to minimal tropical storm intensity. It turned to the west-southwest and re-strengthened to a hurricane on August 4 off the coast of Texas. It weakened again to tropical storm status and made its final landfall near Brownsville, Texas, on August 5 as a strong tropical storm. The system rapidly dissipated over northern Mexico.[8]

While moving over Saint Christopher, the storm killed six people. Heavy rain was reported throughout the Virgin Islands.[22] The hurricane caused the drowning of one person in the Bahamas, and moderate winds produced severe structural damage to the buildings in the archipelago.[23] In Florida, the National Weather Bureau issued storm warnings between Miami to Titusville, while Governor David Sholtz issued a mandatory evacuation for 4,200 residents in vulnerable areas around Lake Okeechobee.[24] Damage in Florida was minimal, limited to minor crops, roofs, and signs.[25] In southern Texas, the hurricane produced moderate damage of $500,000, including disrupted telephone and telegraph lines.[26] The hurricane produced high tides along the coast of Texas, covering parts of South Padre Island,[27] and heavy rains in northern Mexico caused heavy damage.[8]

Hurricane Six

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 13 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) < 940 mbar (hPa) |

The Chesapeake Bay-Potomac Hurricane of 1933

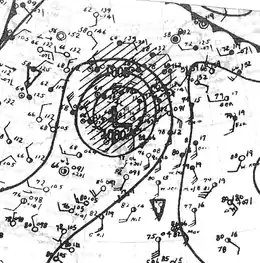

A ship first reported a tropical depression near the Cape Verde islands on August 13. This system would become one of the most destructive hurricanes of the season. The storm moved towards the northwest and attained hurricane status on August 16. The hurricane continued to strengthen, and on August 21, it passed about 150 miles (240 km) southwest of Bermuda as a Category 3 hurricane. St. George's avoided a direct hit but reported wind speeds of up to 64 mph (103 km/h). On August 22, the hurricane turned west-northwest and reached its peak intensity, with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h), equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane in the modern-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. However, it weakened quickly afterwards. On August 23, the storm made landfall on the Outer Banks of North Carolina as a Category 1 hurricane and continued to quickly weaken as it moved inland, away from its energy source.'[28] The storm turned to the north, then to the northeast, passing through Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania before weakening to a tropical depression over New York.[8] The storm became extratropical on August 25 and turned to the east, moving through Atlantic Canada and dissipating on August 28.[9]

The hurricane caused damage ranging from moderate to severe in the corridor between North Carolina and New Jersey, due to high tides and strong winds.[8] In the state of Maryland, the storm's effects resulted in severe crop damage, and many boats and piers were damaged or destroyed due to high tides and storm surge.[8] This tide is notable as the one that separated Ocean City, MD from Assateague & Chincoteague Islands and allowed for the current harbor and inlet to the Atlantic as well as destroying the only rail bridge to the town, which was never rebuilt. The hurricane produced heavy rainfall along its path, with a peak of 13.28 inches (337.3 mm) in York, Pennsylvania.[29] Overall, the hurricane caused $27 million in damage[8] and 31 deaths.[30][31]

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 14 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

The seventh tropical storm of the season was first observed in the eastern Caribbean on August 14. It strengthened to reach winds of 45 mph (72 km/h). After passing just south of Jamaica, the storm turned to the northwest and crossed over both the Isle of Youth and western Cuba on August 18. It curved northward and dissipated west of Florida on August 21.[9]

On Trinidad, rainfall from this storm and a subsequent tropical depression were the heaviest in nine years, which caused rivers to overflow and flooded parts of the island. Several boats were damaged or driven ashore from rough seas. The two storms caused damage to fields, highways, and houses, and caused the loss of crops such as cocoa and bananas. In all, damage totaled $3 million and there were 13 deaths on Trinidad.[32] The storm produced heavy rainfall in eastern Jamaica, including a record 24-hour total of 12.2 inches (310 mm) in the Corporate Area,[33] and Dallas Castle received 20.2 inches (510 mm) in 24 hours.[34] This flooded and damaged properties and water systems in Kingston and Saint Andrew, leading to a water famine until the water mains were fixed. Damage totaled to over $2.5 million,[32] and 70 people were reported killed due to the flooding.[14] Damage was minimal in both Cuba and Florida.[8]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 22 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) <930 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Cuba-Brownsville Hurricane of 1933

The eighth storm of the season was one of two storms in the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season to reach the intensity of a Category 5 strength on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. It formed on August 22 off the west coast of Africa, and for much of its duration it maintained a west-northwest track. The system intensified into a tropical storm on August 26 and into a hurricane on August 28. Passing north of the Lesser Antilles, the hurricane rapidly intensified as it approached the Turks and Caicos islands. It reached Category 5 status and its peak winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) on August 31. Subsequently, it weakened before striking northern Cuba on September 1 with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h).[9] In the country, the hurricane left about 100,000 people homeless and killed over 70 people. Damage was heaviest near the storm's path, and the strong winds destroyed houses and left areas without power. Damage was estimated at $11 million.[35][36][37][nb 4]

After exiting from Cuba, the hurricane entered the Gulf of Mexico and restrengthened. On September 2, it re-attained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h).[9] Initially the hurricane posed a threat to the area around Corpus Christi, Texas, and the local United States Weather Bureau forecaster advised people to stay away from the Texas coastline during the busy Labor Day Weekend. Officials declared martial law in the city and mandated evacuations.[38] However, the hurricane turned more to the west and struck near Brownsville early on September 5 with winds estimated at 125 mph (205 km/h).[9] It quickly dissipated after causing heavy damage in the Rio Grande Valley. High winds caused heavy damage to the citrus crop. The hurricane left $16.9 million in damage and 40 deaths in southern Texas.[39][40]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 23 – August 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

On August 23, another tropical storm was observed north of Puerto Rico. It moved northwestward for three days, slowly strengthening as it moved over the open ocean. The storm turned to the northeast and reached peak sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) a short distance to the west of Bermuda. It began weakening shortly thereafter, and on August 30 the storm became extratropical to the southeast of Newfoundland. It continued to the northeast and was last observed on August 31 over the north-central Atlantic Ocean. It did not cause significant effects on land.[8][15]

Tropical Storm Ten

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed in the Bay of Campeche. It initially moved to the northwest. The cyclone remained a minimal tropical storm for most of its lifetime. On August 29, the storm turned to the west-southwest and made landfall near Tampico, Mexico, dissipating shortly thereafter. The tropical storm caused heavy rains near the coast, although winds were minor. Due to uncertainty as to its course, tropical storm warnings were issued for portions of the southern Texas coastline.[8]

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 31 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 945 mbar (hPa) |

The Treasure Coast Hurricane of 1933

A tropical storm was first observed on August 31, 225 miles (360 km) north-northeast of the island of Antigua. The storm rapidly intensified as it moved quickly to the west-northwest, attaining hurricane status later that day, and major hurricane strength on September 1, while located to the north of Puerto Rico. It continued west-northwestward and attained its peak intensity, with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (225 km/h), on September 2. The hurricane, then at Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, moved through the northern Bahamas at peak intensity and weakened slightly before making landfall on Jupiter, Florida, with winds of 125 mph (200 km/h) on September 4. The system weakened rapidly over Florida to tropical storm status, and after turning to the north, decelerated. The weakening storm slowly moved through Georgia before dissipating near the Georgia/South Carolina border on September 7.[8]

On Eleuthera Island, the Category 4 hurricane blew away the roofs of buildings, wrecked wharves, and lost boats. Hurricane warnings were issued for the eastern Florida coastline, and 3,000 people were evacuated around Lake Okeechobee to safer areas.[41] In southeastern Florida, the strong winds broke many glass windows and downed trees and power lines; severe house damage was reported near the landfall location. The hurricane's powerful winds also severely damaged crops, including 4 million boxes of citrus fruit across the state.[8] In total, Florida suffered $2 million in damage and two deaths.[42]

Hurricane Twelve

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) <947 mbar (hPa) |

The Outer Banks Hurricane of 1933

On September 8, an area of disturbed weather to the east of the Lesser Antilles organized into a tropical storm. It moved north-northeastward, and after a turn to the northwest, the system intensified to hurricane strength on September 10. It steadily intensified and reached a peak strength of 140 mph (225 km/h) on September 15. It slowed as it turned to the north, striking southeastern North Carolina just west of Cape Hatteras as a Category 2 hurricane.[43] After moving through the Outer Banks, the system accelerated to the northeast and became extratropical on September 18 about halfway between Cape Cod and the southern tip of Nova Scotia. The extratropical storm passed over Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Labrador before dissipating east of Greenland on September 22.[8]

Strong winds from the hurricane downed trees and power lines in southeastern North Carolina, causing damage to many houses. The hurricane produced a storm surge that flooded coastal streets with 3 to 4 feet (0.9–1.2 m) of water. In all, the hurricane caused at least 21 deaths, primarily due to drowning in high waters.[8] Damage totaled around $4.5 million.[44]

Hurricane Thirteen

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 960 mbar (hPa) |

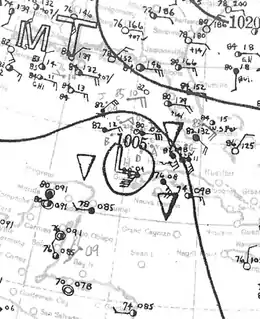

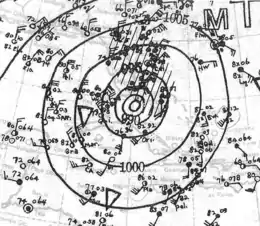

On September 10, as Hurricane Twelve was intensifying over the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, another area of disturbed weather developed into a tropical storm over the western Caribbean Sea off the coast of Guatemala. It moved slowly northward and strengthened, becoming a hurricane on September 12 just east of Belize. On the next day, the hurricane made landfall on the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, and the system weakened to a tropical storm as it moved northwestward across the Yucatán Peninsula. On September 14 it again regained hurricane status over the Bay of Campeche. The hurricane struck Tampico on September 15 and then dissipated.[8]

The storm caused severe damage in Tampico and further inland, leaving several thousand homeless. According to The New York Times, at least 67 people were killed. Tuxpan, south of Tampico, also suffered heavy damage with many houses and office buildings destroyed. Total property losses were estimated at several million dollars.[45]

Hurricane Fourteen

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 16 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) 929 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Tampico Hurricane of 1933

On the other side of the Caribbean Sea, what would become the second Category 5 hurricane of the season, and the 14th tropical storm of the year, was first observed on September 16 to the east of the southern Leeward Islands. The cyclone, then a tropical depression, tracked to the west-northwest through the islands, slowly strengthening into a tropical storm on September 18. It attained hurricane strength on September 19 near Jamaica, then began a period of rapid intensification south of that island. On September 21, a ship measured a central pressure of 929 millibars (27 inHg), indicating that the hurricane had intensified to a peak of 160 mph (260 km/h).[9] Continuing west-northwestward, the hurricane weakened somewhat and made landfall 40 miles (65 km) south of Cozumel Island on September 22. Winds at landfall were estimated to have been 140 mph (230 km/h), equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane by modern classification. The hurricane weakened slightly over the Yucatán Peninsula, but then re-strengthened over the Gulf of Mexico to reach a second peak intensity of 110 mph (175 km/h) on September 24.[9] Shortly thereafter, the storm made landfall near Tampico. It dissipated on September 25 over Mexico.[8]

Near Jamaica, the hurricane caused rough seas, although damage, if any, is unknown.[8] While moving across the Yucatán Peninsula, the storm produced heavy rainfall and strong winds. In Cozumel, the winds destroyed a 300-foot (91 m) pier and several buildings. Rough seas sunk several ships, and one person drowned. The rainfall caused several rivers to overflow, causing flooding and damage to roads and railroads in the state of Veracruz.[46] Many people in low-lying areas around Tampico evacuated for the storm.[47]

Reports indicate much of the city of Tampico was destroyed, and the total number of deaths and injuries amounted to over 5,000. Most of the deaths occurred from flood waters, which were 10 to 15 feet (3.0–4.6 m) deep and covered the entire city;[48] many bodies were washed out to sea, and were never recovered. The flooding washed out roads and railroads, delaying relief efforts into the devastated area. Water and food supplies in and around Tampico were damaged or contaminated, resulting in a threat of famine or disease that further aggravated the situation.[49] Torrential rains caused more flooding, and the powerful winds damaged or destroyed nearly every building in the city and left many homeless.[50] The strong winds downed numerous power lines, leaving the entire city in blackout, and destroyed two large water towers. There were at least 10 cases of looting; all of the perpetrators were executed. Damage in and around Tampico totaled over $10 million,[51] and the storm killed over 184 people.[14]

The thousands of victims took refuge in churches, theatres, and public buildings. Immediately after the storm, the Mexican military placed the city under martial law.[51] Military and federal authorities dispatched trains with food, water, and medicine,[50] and planes bearing engineers and doctors. Mexican president Abelardo L. Rodríguez rallied citizens to aid the affected people in the storm area. The local chamber of deputies allowed $140,000 in funds for the storm victims.[49]

Hurricane Fifteen

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 991 mbar (hPa) |

A storm of extratropical origin developed into a small tropical storm on September 24 southwest of the Azores. Initially the storm moved north-northwestward, and based on ship reports, it is estimated the system intensified into a hurricane on September 26. It passed west of the Azores as it turned to the north-northeast, weakening to a tropical storm later that day. On September 27 the storm became extratropical, and the next day it dissipated.[9]

Tropical Storm Sixteen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 1 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1012 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical disturbance moved through the Lesser Antilles in late September. After crossing Hispaniola, a tropical depression developed on October 1 north of the Dominican Republic. It moved northwestward initially and quickly intensified into a tropical storm. It had a broad wind field, indicating characteristics of a subtropical cyclone. After reaching peak winds of 45 mph (72 km/h), the storm turned to the northeast and weakened. It dissipated on October 4 to the southeast of Bermuda.[9]

Hurricane Seventeen

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 1 – October 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 940 mbar (hPa) |

On October 1, a tropical storm developed off the northeast coast of Nicaragua. It moved slowly northward and steadily intensified, becoming a hurricane on October 3 just west of Jamaica. The hurricane turned to the north-northwest and hit the Cuban province of La Habana with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) on October 4. The hurricane passed over Havana and turned to the northeast and strengthened, becoming a major hurricane as it moved south of Miami, Florida. The hurricane reached a peak intensity of 125 mph (205 km/h) while passing through the Bahamas on October 6. The hurricane weakened as it accelerated to the northeast, and it became extratropical on October 8 to the south of Nova Scotia. It paralleled the Nova Scotia coast, turned to the east-southeast, and lost its tropical characteristics on October 9 over the open north Atlantic Ocean.[15]

One person was killed in Jamaica due to flooding.[52] In Cuba, people boarded up numerous buildings, and emergency workers assisted authorities in spreading the word about the impending storm; residents in vulnerable areas evacuated to shelters on higher ground. The hurricane's powerful winds destroyed several houses in Camagüey, and heavy rainfall overflowed numerous rivers in low-lying districts.[53] The winds damaged and disrupted telephone and telegraph lines and injured a few people in Havana. Despite government orders for police to kill any looters, large-scale looting occurred in Havana after the storm. Two looters were shot to death, and a third was injured. Two civilians were also wounded by snipers who fired to disperse thieves.[54] Residents in southeast Florida boarded up for the storm while the National Weather Bureau issued storm warnings for portions of the coastline.[53] The hurricane produced strong winds and rain in the Florida Keys and extreme southern Florida, but damage was minimal.[54] In northwest Miami, the hurricane spawned a tornado that damaged three houses and injured two.[55][56] In Nova Scotia, the former hurricane left heavy damage to crops due to strong winds and heavy rain. Sunken boats killed nine people, and damage was estimated at around $1 million (1933 CAD), including $250,000 in lost apple crop.[57][nb 5]

Hurricane Eighteen

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 25 – November 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

After a two-week period of inactivity, a tropical depression was detected in the western Caribbean Sea on October 25. It moved to the east-northeast then curved to the northwest while slowly intensifying. On October 29, it strengthened into a hurricane near Jamaica and reached peak winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) before striking the western portion of the island. The hurricane turned to the northeast and weakened. It made landfall on southeastern Cuba as a strong tropical storm on October 31. The weakening storm changed its course to the north-northwest, as it drifted through Cuba and the Bahamas. On November 4, the storm turned once more to the northeast, accelerated, and was absorbed by an approaching cold front on November 7 near Bermuda.[9]

While moving near western Jamaica, the hurricane produced strong winds of about 80 mph (130 km/h),[9] which wrecked about 90% of the banana crop.[61] One plantation lost 500 banana trees, and there was also damage to corn, coffee, and yams.[62] Many houses were wrecked or washed away,[61] leaving hundreds homeless.[62] The storm cut power and telegraph lines and blocked roads, limiting communication.[61] Rail lines were cut, and small bridges were washed away.[63] Damage was estimated at $3 million,[61] and there were 23 deaths.[62] The storm also produced strong winds and rainfall in Cuba.[63]

Tropical Storm Nineteen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 26 – October 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

Almost simultaneous to Hurricane 18, a tropical storm developed a short distance east of the central Bahamas on October 26. It moved north-northeastward, then northeastward, steadily strengthening along its path. On October 27, a barometric pressure of 993 mbar (29.32 inHg) was recorded within the storm, and on October 28 the storm reached a peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h). On October 29, the storm became extratropical and turned north to hit Nova Scotia. Wedged between two high pressure systems, it continued northward until dissipating over extreme eastern portions of Quebec on October 30.[64]

In Atlantic Canada, the former tropical storm produced winds of 52 mph (83 km/h) in Nova Scotia, along with heavy rainfall of 2.3 in (58 mm) in Amherst. The storm sank one boat and washed another ashore. Winds were strong enough to knock down telephone and telegraph lines, mainly due to fallen trees which also covered roads and damaged houses. Flooding washed out several bridges and roads, covering one highway with 6 ft (1.8 m) of water, and entered the basements of houses. In New Brunswick, the storm damaged or destroyed 72 bridges. One man was struck by a car due to poor visibility from the storm.[65]

Tropical Storm Twenty

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 15 – November 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) |

After another calm period, the final tropical storm of the season was first observed on November 15 in the southwestern Caribbean Sea. It moved slowly westward, never strengthening beyond a minimal tropical storm in its short lifetime. On November 16, it struck the southeastern coast of Nicaragua, and it dissipated soon after on November 17.[15]

Seasonal effects

This is a table of the storms in 1933 and their landfall(s) in bold, if any. The minimum pressures, in most cases, are based on limited observations and may not have occurred at their peak intensity.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 14–19 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1001 | Central America, Mexico (Tabasco) | None | 0 | |||

| Two | June 24–July 7 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 965 | Trinidad, Venezuela, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Western Cuba, Tamaulipas | 7.2 | 35 | |||

| Three | July 14–24 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 999 | Lesser Antilles, Jamaica, Belize, Yucatan Peninsula, Texas | 2 | 0 | |||

| Four | July 24–27 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1008 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Five | July 24–August 5 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 975 | Lesser Antilles, Bahamas, Florida, Texas | .5 | 0 | |||

| Six | August 13–25 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 940 | Bermuda, Eastern United States (North Carolina) | 27 | 31 | |||

| Seven | August 14–21 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1007 | Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Cuba | 2.5 | 83 | |||

| Eight | August 22–September 5 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 930 | Turks and Caicos, Cuba, Florida Keys, Texas | 27.9 | 179 | |||

| Nine | August 23–30 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 999 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Ten | August 26–30 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1002 | Tamaulipas | None | 0 | |||

| Eleven | August 31–September 7 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 945 | Bahamas, Florida, Southeast United States | 2 | 2 | |||

| Twelve | September 8–18 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 947 | North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic states, Northeastern United States, Atlantic Canada, Greenland | 4.5 | 21 | |||

| Thirteen | September 10–16 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 960 | Tamaulipas | Unknown | 67 | |||

| Fourteen | September 16–25 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 929 | Cayman Islands,Yucatan Peninsula, Tamaulipas | 10 | 184 | |||

| Fifteen | September 24–27 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 991 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Sixteen | October 1–4 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1012 | Bahamas | None | 0 | |||

| Seventeen | October 1–7 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 940 | Nicaragua, Honduras, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Florida, Bahamas | 1.1 | 10 | |||

| Eighteen | October 25–November 7 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 982 | Jamaica, Cuba | 3 | 23 | |||

| Nineteen | October 26–28 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 990 | Atlantic Canada | Unknown | 0 | |||

| Twenty | November 15–17 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 996 | Nicaragua | Unknown | 0 | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 20 systems | May 14–November 17 | 160 (260) | 929 | ~86.6 | 651 | |||||

Notes

- The Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale was developed in 1971,[4] and has been retroactively applied to the entirety of the Atlantic hurricane database.[5]

- There is an undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910, due to the lack of modern observation techniques, see Tropical cyclone observation. This may have led to significantly lower ACE ratings for hurricane seasons prior to 1910.[6][7]

- All damage totals are in 1933 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

- All damage totals are in 1933 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

- $1 million in 1933 Canadian dollars (CAD) would be $20.5 million in 2013 CAD, adjusted for inflation figures from the Bank of Canada.[58] When converted to USD, the total would be $20.1 million as provided by the Oanda Corporation,[59] which would be about $1.1 million when adjusted for inflation to 1933.[60]

References

- Linker, Josh (September 16, 2020). "Why This Hurricane Season Isn't as Active as It Seems". baynews9.com. St. Petersburg, Florida: Bay News 9. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Landsea, Christopher W. (May 1, 2007). "Counting Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Back to 1900" (PDF). Eos. Vol. 88 no. 18. Washington, D.C.: John Wiley & Sons for the American Geophysical Union. pp. 197–208. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Landsea, Christopher W.; Hagen, Andrew; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Glenn, David A.; Santiago, Adrian; Stratham-Sakoskie, Donna; Dickinson, Michael (August 15, 2014). "A Reanalysis of the 1931–43 Atlantic Hurricane Database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 27 (16): 6093–6118. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Jack Williams (May 17, 2005). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 24, 2006. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- Chronological List of All Continental United States Hurricanes: 1851-2012 (Report). Hurricane Research Division. June 2013. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Christopher W. Landsea, Hurricane Research Division (May 8, 2010). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- Christoper W. Landsea, Hurricane Research Division (March 26, 2014). "HURDAT Re-analysis Original vs. Revised HURDAT". NOAA. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- Charles L. Mitchell (1933). "Tropical Disturbances of July 1933" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 61 (7): 200–201. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..200M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<200b:TDOJ>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- Chris Landsea; et al. (2012). 1933 Storm 1 – 2012 Revision (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- Andy Hatzos (January 5, 2010). "Earliest Hurricane Research". Archived from the original on August 11, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT (Report). Hurricane Research Division. April 2012. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- Stacy Stewart (January 6, 2006). Tropical Storm Zeta Discussion Thirty (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- Pielke; Rubiera; Landsea; Fernandez & Klien (2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America & The Caribbean" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- Rappaport & Partagas (1997). "The Deadliest Atlantic Hurricanes, 1492–1996". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- Unisys Corporation (2006). "1933 Atlantic hurricane season". Archived from the original on August 19, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

- The Daily Gleaner (July 18, 1933). "Torrential Rains Create Havoc in Kingston and St. Andrews". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- The Daily Gleaner (July 20, 1933). "Burst Rivers Flooded Roads in Villages". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- The Ada Evening News (July 22, 1933). "Storm Threatens Coast of Texas". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- David Roth (January 14, 2010). "Louisiana Hurricane History" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. pp. 32–33. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- Port Arthur News (July 27, 1933). "Rises Predicted". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- R. J. Martin (1933). "The Weather of 1933 in the United States" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- "Six Are Reported Killed in St. Christopher Blow". The Palm Beach Post. July 26, 1933. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Bismarck Tribune (July 28, 1933). "Storm Hits Bahamas". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- Port Arthur News (July 30, 1933). "Tropical Storm Nears Florida". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- Times Herald (July 31, 1933). "Florida Effects from Hurricane". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- The Daily Northwestern (August 5, 1933). "Tropical Hurricane Blows Self Out in Mountainous Region". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- David Roth (January 17, 2010). "Texas Hurricane History: Early 20th century" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. pp. 41–42. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- David Roth (March 1, 2007). Early Twentieth Century Virginia Hurricane History (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Roth, David M.; Cobb, Hugh (2001). "Virginia Hurricane History". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved September 5, 2006.

- Hurricanecity.com (2006). "Ocean City, Maryland hurricanes". Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- Winnipeg Free Press (August 19, 1933). "Tail-end of Jamaica storm causes heavy damage on Trinidad". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- The Daily Gleaner (August 17, 1933). "Hurricane Passes South of Island". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- "What is a Hurricane?". The Daily Gleaner. May 29, 1982. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- "100 Dead, Cuba Hurricane". The Courier-Mail. Australian Press Association. September 5, 1933. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- "Death, Damage Left in Wake of Hurricane in Cuba". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. September 2, 1933. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- Roger A. Pielke Jr.; Jose Rubiera; Christopher Landsea; Mario L. Fernández; Roberta Klein (August 2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials" (PDF). National Hazards Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 108. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Hurricane #11, 1933 (Report). Corpus Christi National Weather Service. February 2000. Archived from the original on November 8, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- Mary O. Souder (September 1933). "Severe Local Storms, September 1933" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 61 (9): 291. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..291.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<291:SLSS>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- David M. Roth (February 4, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. p. 42. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- "Throngs Flee as Hurricane Perils Florida". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. September 4, 1933. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Williams & Duedall (1997). "Tropical storms and Hurricanes in Florida" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2006.

- Blake; Rappaport & Landsea (2006). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones (1851 to 2006)" (PDF). NOAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- Mary Souder (1933). "Severe Local Storms, September 1933" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- "67 Mexicans Die In Storm". The New York Times. September 17, 1933.

- "Storm Crossing Yucatan; Damage Reported Heavy". Associated Press. September 22, 1933.

- "Storm Moving Through Gulf". Associated Press. September 23, 1933.

- "Port City of Mexico Destroyed by Storm". Associated Press. September 26, 1933.

- Galveston Daily News (September 28, 1933). "Storm Relief".

- "Tampico Flooded After Hurricane". Associated Press. September 28, 1933.

- The Hammond Times (September 29, 1933). "Tampico Hurricane".

- "Gale Hits Cuba: Heading for U.S." The Pittsburgh Press. United Press. October 4, 1933. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- "Gale Hits Cuba: Heading for U.S." The Pittsburgh Press. United Press. October 4, 1933. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- "Four Killed in Havana During Storm Looting". Lewiston Evening Journal. October 5, 1933. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Mary O. Souder (October 1933). "Severe Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 61 (10): 319. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..319.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<319:slso>2.0.co;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2005. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- "Florida Coast Escapes Fury of Hurricane". Lewiston Evening Journal. Associated Press. October 5, 1933. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- Detailed Storm Impacts - 1933-18 (Report). Environment Canada. November 18, 2009. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- "Inflation Calculator". Bank of Canada. 2013. Archived from the original on September 21, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- "Historical Exchange Rates". Oanda Corporation. 2013. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013). "CPI Inflation Calculator". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- "Toll of Hurricane in Jamaica Rises". The Miami News. Associated Press. November 2, 1933. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- The Daily Gleaner (November 2, 1933). "Hurricane Sufferers in the West are Calling for Help". Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- "Jamaica Swept by Heavy Gale". The Leader-Post. October 31, 1933. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Willis E. Hurd (1933). "Weather of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans" (PDF). Marine Division. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

- Detailed Storm Impacts - 1933-20 (Report). Environment Canada. November 18, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1933 Atlantic hurricane season. |