Satellite Instructional Television Experiment

Satellite Instructional Television Experiment or SITE was an experimental satellite communications project launched in India in 1975, designed jointly by NASA and the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO). The project made available informational television programs to rural India. The main objectives of the experiment were to educate the financially backward and academically illiterate people of India on various issues via satellite broadcasting, and also to help India gain technical experience in the field of satellite communications.

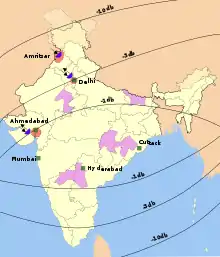

The experiment ran for one year from 1 August 1975 to 31 July 1976, covering more than 2400 villages in 20 districts of six Indian states and territories (Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan). The television programs were produced by All India Radio and broadcast by NASA's ATS-6 satellite stationed above India for the duration of the project. The project was supported by various international agencies such as the UNDP, UNESCO, UNICEF and ITU. The experiment was successful, as it played a major role in helping develop India's own satellite program, INSAT.[1] The project showed that India could use advanced technology to fulfill the socio-economic needs of the country. SITE was followed by similar experiments in various countries, which showed the important role satellite TV could play in providing education.

Background

As part of its Applications Technology Satellites program in the 1960s, NASA sought to field test the direct broadcast of television programs to terrestrial receivers via satellite and shortlisted India, Brazil and the People's Republic of China as potential sites to stage the test. The country which would receive these broadcasts would have to be large enough and also close to the equator for testing a direct-broadcast satellite. While the communist regime of China was not recognized at the time by the U.S., Brazil was also ruled out as its population was concentrated in the cities, affecting the outreach of the broadcast across the country. As a consequence, India emerged as the only suitable candidate; however, its strained relationship with the U.S. prevented the U.S. government from directly asking for its assistance, preferring India to make the first request for assistance for its own nascent space program.[2]

At the same time, India was trying to launch its national space program under the leadership of Vikram Sarabhai. India was interested in the role of satellites for the purpose of communication and asked UNESCO to undertake a feasibility study for a project in that field. Between 18 November 1967 and 8 December 1967, UNESCO sent an expert mission to India to prepare a report on a pilot project in the use of satellite communication. The expert panel concluded that the such a project would be feasible. Following the report, a study team of three engineers from India visited USA and France in June 1967, and came to the conclusion that India could meet the technical requirements for the project.[3] Following this, the Indian government set up the National Satellite Communications Group SATCOM in 1968 to look into the possible uses of a synchronous communications satellite for India. This group consisted of representatives from various cabinet ministries, ISRO and All India Radio (AIR) And Doordarshan. The group recommended that India should use the ATS-6 satellite– a second generation satellite developed by NASA– for an experiment in educational television.[3]

Arnold Frutkin, then NASA's director of international programs, arranged to have the Vikram Sarabhai approach NASA for help. Sarabhai saw this as a great opportunity for India to expand its space program and to train Indian scientists and engineers. Consequently, the Indian Department of Atomic Energy and NASA signed an agreement regarding SITE in 1969.[4] The experiment was launched on 1 August 1975.

| India-USA Memorandum of Understanding Signed, ESD Created | 18 September 1969 |

| First INDIA-USA SITE Meeting | 1 April 1970 |

| AVID (NOW SSG) Created | 1 June 1971 |

| AIR Base Production Centres Operational | August 1974 |

| Bombay SITE Studio Commissioned | 15 August 1974 |

| DRS Deployment Phase I Begins | 15 November 1974 |

| ESCES Operational | January 1975 |

| Village Selection Over | 1 February 1975 |

| DRS Deployment Phase II Begins | March 1975 |

| ESCES and DRS Checkout With S/C Simulator | March 1975 |

| Tenth ISRO-NASA Meeting | April 1975 |

| Delivery Of All DRS Units Completed By ECIL | April 1975 |

| First Programme Produced In Ahmedabad Studio | 8 May 1975 |

| ATS-6 Begins Moving From 94°W | 21 May 1975 |

| ESCES Checkout With INTELSAT | June 1975 |

| ATS-6 Visible To ESCES | 13 June 1975 |

| DRS In Villages Receive Signals | 14 June 1975 |

| Amritsar Earth Station Receives Signals | 17 June 1975 |

| ATS-6 Arrives At 35° E | 27 June 1975 |

| Delhi Earth Station Operational | 3 July 1975 |

| DRS Checkout | 3 to 5 July 1975 |

| Nadiad TV Transmitter Operational | 7 July 1975 |

| Baseline For SITE Impact Survey (Adults) Completed | 7 July 1975 |

| SITE System Demonstration To Chairman, ISRO | 9 and 10 July 1975 |

| Start Of SITE | 1 August 1975 |

Objectives

As per the Memorandum of Understanding signed between the two countries, the objectives of the project were divided into two parts—general objectives and specific objectives. The general objectives of the project were to:

- gain experience in the development, testing and management of a satellite-based instructional television system particularly in rural areas and to determine optimal system parameters;

- demonstrate the potential value of satellite technology in the rapid development of effective mass communications in developing countries;

- demonstrate the potential value of satellite broadcast TV in the practical instruction of village inhabitants; and

- stimulate national development in India, with important managerial, economic, technological and social implications.

The primary social objectives from an Indian perspective were to educate the populace about issues related to family planning, agricultural practices and national integration. The secondary objectives were to impart general school and adult education, train teachers, improve other occupational skills and to improve general health and hygiene through the medium of satellite broadcasts. Besides these social objectives, India also wanted to gain experience in all the technical aspects of the system, including broadcast and reception facilities and TV program material.

The primary US objective was to test the design and functioning of an efficient, medium-power, wide bandspace-borne FM transmitter, operating in the 800–900 MHz band and gain experience on the utilisation of this space application.[4]

International collaboration

A joint ISRO-NASA working group was established even before the Memorandum of Understanding was signed. This working group studied the possibility of using a communications satellite for TV broadcast in India. After the MoU was signed, many review meetings were held between NASA and ISRO scientists. Indian scientists visited NASA to study front-end converters and earth station operations. On India's request, the INTELSAT-III and Arvi Earth Station organisation agreed to provide free satellite time for pre-SITE testing.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) provided assistance of $500,000 for setting up the Experimental Satellite Communications Earth Station (ESCES) at Ahmedabad and nominated the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) as the executing agency for this project. The UNDP provided another $1.5 million, for setting up a TV studio at Ahmedabad and a TV transmitter at Pij in Kheda district. It also gave assistance for setting up a TV Training Institute to train many of the programme production staff who would join All India Radio to work on SITE. UNESCO was the executing agency for this project. UNICEF contributed to SITE by sponsoring 21 film modules produced by Shyam Benegal, a noted Indian filmmaker. This resulted in a lot of interaction between filmmakers and folk-artists. Shyam Benegal went on to include many of these artists in his children's feature film Charandas Chor (1975).[6]

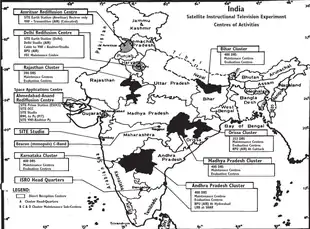

Technical details

The production of the television programmes was decentralised, with three Base Production Centres located at Delhi, Cuttack and Hyderabad, and an ISRO studio located in Mumbai. Each of the centres had a production studio, three IVC tape recorders, two 16 mm. projectors, a slide Projector in Telecine and audio equipment like tape desks and turntables. Each centre also had 2–3 full-fledged synchronised sound camera units, an editing table (Delhi had two) and a film processing plant. There was also a sound dubbing studio equipped with a pilot tone recording plant and an audio mixing console.[7]

The television programmes prepared by the Indian government at the four studios were transmitted at 6 GHz to ATS 6 from one of two ground stations located in Delhi and Ahmedabad. These signals were then re-transmitted at 860 MHz by the satellite, which were directly received in 2000 villages by community television receivers with 3 m parabolic antennas. Regular television stations also received the signals and broadcast them to another 3000 villages in the standard VHF television band. Each television signal had two audio channels to carry audio in two major languages of each cluster.[8] This setup was called the Direct Reception System (DRS). Apart from the direct broadcasts, the earth station at Ahmedabad was micro-wave linked to the TV transmitter built in the village of Pij. The Delhi studio was linked to the terrestrial TV transmitters of AIR. A receive-only station was built in Amritsar and linked to the local TV transmitter.[9]

The DRS undertook terrestrial broadcasting for large cities and direct broadcasting to SITE television sets for remote villages. However, it did not provide for small towns where the TV set density was higher than in the villages while not as much as in a city. The concept of a low-power limited rebroadcast (LRB) TV transmitter system was evolved to overcome such situations. The LRB consisted of a simple receiver system having a 4.5 m chicken-mesh parabolic antenna with a low-noise block converter, that served as the front-end for a low-power TV transmitter at the same location. Two suitable locations, Sambalpur in Orissa (75 villages) and Muzaffarpur in Bihar (110 villages), were tentatively identified for implementing LRB transmitter systems. This experiment was expected to provide useful data on the trade-off between DRS and LRB. However, due to financial constraints, these two LRBs had to be shelved, and instead an LRB was set up at SHAR, Sriharikota.[10]

Village selection

As the broadcasting time was limited, it was decided that the direct reception receivers would only be installed in 2400 villages in six regions spread across the country. Technical and social criteria were used to select suitable areas to conduct this experiment.[11] A computer program was specially designed at ISRO to help make this selection. As one of the aims of the experiment was to study the potential of TV as a medium of development, the villages were chosen specifically for their backwardness. According to the 1971 census of India, the states having the most number of backward districts in the country were Orissa, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Karnataka. Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal were eventually left out, as they were slated to get terrestrial television by the time SITE would end. SITE was launched in twenty districts spread across the other six states. Each of the states thus selected was called a "cluster". In each cluster, 3–4 districts, each containing around 1000 villages, were identified. Finally, around 400 villages were chosen in each cluster.[11] Close to 80% villages selected for SITE did not have electricity in the buildings where the SITE TV sets would be installed. A special project called Operation Electricity was launched to urgently electrify the villages before the start of SITE. 150 villages would have television sets running on solar cells and batteries.[12] These sets were specially designed by Indian engineers with help from NASA.[2]

| Cluster | District | Maintenance centers |

|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | Hyderabad | Hyderabad |

| Kurnool | Nandyal | |

| Medak | Sangareddy | |

| Mahbubnagar | Nagarkurnool | |

| Karnataka | Gulbarga | Gulbarga, Bagalkot |

| Raichur | Raichur | |

| Bijapur | Bijapur | |

| Bihar | Muzaffarpur | Muzaffarpur |

| Champaran | Motihari | |

| Saharsa | Saharsa | |

| Darbhanga | Darbhanga, Samastipur | |

| Madhya Pradesh | Raipur* | Raipur, Mahasamund |

| Bilaspur* | Bilaspur | |

| Durg* | Rajnandgaon | |

| Orissa | Sambalpur | Sambalpur |

| Dhenkanal | Dhenkanal, Angul | |

| Baudh Khandmals | Boudh | |

| Rajasthan | Jaipur | Jaipur, Chomu |

| Kota | Kota | |

| Sawai Madhopur | Gangapur |

* These districts are now located in the state of Chhattisgarh.

Programming

All India Radio had the main responsibility for programme generation and the programmes were made in consultation with the government. Special committees on education, agriculture, health and family planning identified their own programme priorities and conveyed it to AIR.

Two types of programmes were prepared for broadcasting: educational television (ETV) and instructional television (ITV). ETV programmes were meant for school children and focussed on interesting and creative educational programmes. These programmes were broadcast for 1.5 hours during school hours. During holidays, this time was used to broadcast Teacher Training Programmes designed to train almost 100,000 primary school teachers during the duration of the SITE. The ITV programmes were meant for adult audiences, mainly to those who were illiterate. They were broadcast for 2.5 hours during the evenings. The programmes covered health, hygiene, family planning, nutrition, improved practices in agriculture and events of national importance. Thus, the programmes were beamed for four hours daily in two transmissions. The targeted audience was categorised into four linguistic groups—Hindi, Oriya, Telugu and Kannada—and programmes were produced according to the language spoken in the cluster.[14]

Due to linguistic and cultural differences, it was agreed that all core programmes would be cluster-specific, and would be in the primary language of the region. A brief commentary giving the gist of the programme would be available on the second audio channel, to keep up the interest of the audience in other language regions. All clusters would also receive 30 minutes of common programmes, including news, which would be broadcast only in Hindi.[15]

| 6:00 | 7:00 | 7:30 | 7:50-8:30 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mins. | Bihar/Madhya Pradesh/Rajasthan | Common Programme | Mins. | Orissa | Mins. | Andhra Pradesh/Karnataka |

| 10 | Agriculture (MP) | News (all clusters) | 10 | Agriculture | 10 | Agriculture (AP) |

| 20 | Cultural | 10 | Cultural | 10 | Cultural (Urdu) | |

| 10 | Health | 10 | Cultural (Karnataka) | |||

| 15 | General Education/Information (Film) | 10 | General Education Community Matters (Karnataka) | |||

| 5 | Short Film |

Evaluation

The social research and evaluation of SITE was done by ISRO's special SITE Research and Evaluation Cell (REC). The REC consisted of around 100 persons who were located in each of the SITE clusters, at the SITE studio in Bombay, and at the headquarters of the REC in Ahmedabad. The research design was finalized by the SITE Social Science Research Co-ordination Committee under the chairmanship of Dr. M. S. Gore, Director of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Bombay. Impact on primary school children was studied under a joint project involving ISRO and the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT). The overall evaluation design was divided into three stages. The first stage, the formative or input research, was a detailed study of the potential audience. The second stage, process evaluation, was the evaluation carried out during the life-time of SITE. This evaluation provided information about the reaction of the villagers to different programmes. The third stage, the summative evaluation, involved a number of different studies to measure the impact of SITE. These included the Impact Survey (Adults) to measure the impact on adults, SITE Impact Survey Children (SIS-C) to measure the impact on school children, and the qualitative anthropology study to measure, at a macro-level, the change brought by TV in rural society.[17]

Besides the social evaluation, a technical evaluation was also carried out to help India develop future systems. All major sub-systems of the earth station were tested and evaluated before SITE was launched. This was done firstly using a spacecraft simulator from NASA, then using the Indian Ocean INTELSAT satellite and finally using the ATS-6 satellite. All the components of the Direct Reception System were also thoroughly tested. The TV set was tested by the British Aircraft Corporation. The 3-meter antenna was tested thoroughly before deciding on the final design. Data on failure rates was collected and analysis of the first 1800 failures was carried out to help design future DRS systems.[18]

Impact

As decided in the original agreement, the SITE program ended in July, 1976 and NASA shifted its ATS satellite away from India, despite demands from Indian villagers, journalists and others such as noted writer Arthur C. Clarke (who was presented with a SITE television set in Sri Lanka) for NASA to continue the experiment.[2]

The SITE transmissions had a very significant impact in the Indian villages. For the entire year, thousands of villagers gathered around the TV set and watched the shows. Studies were conducted on the social impact of the experiment and on viewership trends. It was found that general interest and viewership were highest in the first few months of the program (200 to 600 people per TV set) and then declined gradually (60 to 80 people per TV set). This decline was due to several factors, including faults developing in the television equipment, failure in electricity supply, and hardware defects, as also the villagers' pre-occupation with domestic or agricultural work. Impact on the rural population was highest in the fields of agriculture and family planning. Nearly 52% of viewers reported themselves amenable to applying the new knowledge gained by them.[19]

Similar experiments were conducted in the Appalachian region, Rocky Mountains, Alaska, Canada, China and Latin America in the mid-seventies and early eighties. These experiments demonstrated that satellite TV could play a very important role in providing education.[20]

Before SITE, the focus was on the use of terrestrial transmission for television signals. But SITE showed that India could make use of advanced technology to fulfill the socio-economic needs of the country. This led to an increased focus on satellite broadcasting in India. ISRO began preparations for a country-wide satellite system. After conducting several technical experiments, the Indian National Satellite System was launched by ISRO in 1982.[21] The Indian space program remained committed to the goal of using satellites for educational purposes. In September 2004, India launched EDUSAT, which was the first satellite in the world built exclusively to serve the educational sector. EDUSAT is used to meet the demand for an interactive satellite-based distance education system for India.[22][23]

References

- Evaluation Report On Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE) (PDF). Planning Commission, India. 1981. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- Chander, Romesh; Karnik, Kiran (1976). Planning for Satellite Broadcasting: The Indian Instructional TV experiment (PDF). UNESCO Press. ISBN 92-3-101392-0.

- Srinivasan, Raman (1997). "16: No Free Launch: Designing the Indian National Satellite". In Butrica, Andrew J. (ed.). Beyond The Ionosphere: Fifty Years of Satellite Communication. The NASA History Series.

- Pal, Y.; H. Bloom; S. Harris (October 7, 1975). "Some Experiences in Preparing for a Satellite Television Experiment for Rural India (and Discussion)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. The Royal Society. 345 (1643): 437–447. Bibcode:1975RSPSA.345..437P. doi:10.1098/rspa.1975.0150. JSTOR 19751007. OCLC 43473942.

- Intelsat III AND Arvi Earth Station

Notes

- Paterson, Chris. "Satellite". Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- Butrica (1997), Chapter 16.

- Chander (1976), p. 9.

- "Memorandum of understanding between the government of India and the government of the United States of America regarding India – U. S. A. ITV satellite experiment project" (PDF). Government of India, NASA. 1969-09-18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- "Satellite Instructional Television Experiment Memoirs" (PDF). SAC.gov.in. 12 August 2015. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Chander (1976), p. 49.

- Chander (1976), p. 28.

- Martin, Donald. "Experimental Satellites". Communication Satellites (4th ed.). Aerospace Press. ISBN 1-884989-19-5.

- Pal (1975), p. 439

- Chander (1976), p. 14.

- Chander (1976), p. 15.

- Pal (1975), p. 442-443

- Chander (1976), p. 17.

- Planning Commission (1981), p. 1.

- Chander (1976), p. 27.

- Chander (1976), p. 56.

- Chander (1976), pp. 44–46.

- Chander (1976), pp. 47–48.

- Planning Commission (1981), pp. 3–4.

- Rao, U. R. "Space Technology for Universal Education". The First Ten K R Narayanan Orations: Essays by Eminent Persons on the Rapidly Transforming Indian Economy. Australia South Asia Research Centre, ANU. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- Joshi, Subhash (August 2000). "25 years of satellite broadcasting in India". Orbicom. Archived from the original on 2008-08-02. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- "EDUSAT launched successfully". The Hindu. 2004-09-20. Archived from the original on 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- "Education satellite launched". Focus magazine. BBC. 2004-09-21. Retrieved 2007-11-27.