Saint James Cavalier

Saint James Cavalier (Maltese: Kavallier ta' San Ġakbu) is a 16th-century cavalier in Valletta, Malta, which was built by the Order of St John. It overlooks St James' Bastion, a large obtuse-angled bastion forming part of the Valletta Land Front. St James was one of nine planned cavaliers in the city, although eventually only two were built, the other one being the identical Saint John's Cavalier. It was designed by the Italian military engineer Francesco Laparelli, while its construction was overseen by his Maltese assistant Girolamo Cassar. St James Cavalier never saw use in any military conflict, but it played a role during the Rising of the Priests in 1775.

| Saint James Cavalier | |

|---|---|

Kavallier ta' San Ġakbu | |

| Part of the fortifications of Valletta | |

| Valletta, Malta | |

Saint James Cavalier | |

Logo of Spazju Kreattiv, St James Cavalier | |

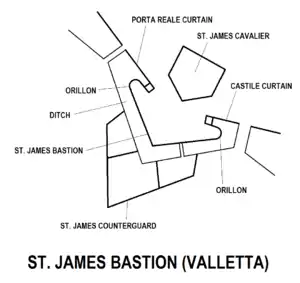

Map of St. James Bastion with its cavalier and counterguard | |

| Coordinates | 35°53′44.83″N 14°30′37.09″E |

| Type | Cavalier |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Government of Malta |

| Controlled by | Fondazzjoni Kreattività |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Intact |

| Website | www.kreattivita.org |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1560s |

| Built by | Order of Saint John |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Events | Rising of the Priests |

The cavalier is located in Castille Square, close to Auberge de Castille, the Central Bank of Malta, the Parliament House, the Malta Stock Exchange and the post office at Dar Annona. The cavalier was restored as part of Malta's Millennium Project, and it is now a cultural centre known as Spazju Kreattiv (Maltese for Creative Space).

History

Hospitaller rule

Following the Great Siege of Malta of 1565, in which the Ottoman Empire attempted to take over Malta but failed to do so, the Order of St John decided to settle permanently on the island. The Order decided to build a new fortified city as their new capital, and it was called Valletta after Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette. In order to do this, De Valette asked for financial aid from various European rulers. Pope Pius V not only helped out financially, but he also sent the Italian military engineer Francesco Laparelli to Malta in order to design the new capital's fortifications. Construction of the city began in March 1566, and work continued throughout the 1570s. Following Laparelli's departure from Malta and his subsequent death, construction of the city was entrusted to his Maltese assistant, the architect and military engineer Girolamo Cassar.[1] St James Cavalier, in its early years, was often known as the Tower of the Cavalier, Cavalier Tower or the variants.[2]

St James Cavalier was one of the first buildings to be built in Valletta, along with the Church of Our Lady of Victories and the rest of the fortifications.[3] The cavalier was built as a raised platform on which guns were placed to defend the city against attacks from the landward side, in the area where the town of Floriana was later built. As well as prohibiting entry, St James could also threaten those who had already breached the city's defences. It was linked to Saint John's Cavalier by a now-blocked underground passageway.[4]

The cavalier was also used as a gun signalling station. Three rounds were fired every day, at sunrise, noon and sunset. The former and the latter marked the opening and closing of the city gates. Gun signals continued to be fired from the cavalier until around 1800, when they began to be fired from the nearby Saluting Battery.[5]

In 1686, during the magistracy of Gregorio Carafa, a small building known as Dar Annona was grafted on the east flank of the cavalier. The building originally housed the Università dei Grani,[6] and it is now a post office.[7]

On 8 September 1775, St James Cavalier was captured by rebels during the Rising of the Priests. The Order's flag was lowered and a banner of Saint Paul was raised instead. Fort Saint Elmo was also taken over by the rebels, but the Order managed to retake it after a brief exchange of fire. Soon after the fort was taken, the rebels at St James surrendered. Three of them were executed, while the others were exiled or imprisoned. The heads of the three executed men were displayed on the corners of St James Cavalier,[8] but were removed soon after Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc was elected Grand Master in November of the same year.[9]

19th and 20th centuries

After taking control of Malta in the beginning of the 19th century, the British converted the cavalier into an officers' mess, a place where soldiers could socialize. Some modifications were made to the structure at this point, including replacing the ramp leading to the roof by a staircase, and increasing the number of rooms by building an arched ceiling within the ground floor room, therefore creating two stories where there had been only one. Changes were also made to help combat humidity.[10]

Later on, two cisterns were excavated within the cavalier to store water pumped to Valletta via the Wignacourt Aqueduct. The cavalier stored water for the entire city.[10]

In 1853, a proposal was made to demolish the cavalier to make way for a hospital, but nothing materialized.[11]

In World War II, the building was also used as a bomb shelter, while its upper floor became a food store for the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes.[10]

In the 1970s, the Government Printing Press moved from the Grandmaster's Palace to St James, and it remained there until new premises at Marsa Industrial Estate were opened in 1996.[12]

Cultural centre

In the 1990s, the Government of Malta commissioned a Master Plan for the rehabilitation of Valletta and its outskirts. The project included restoring St James Cavalier and converting it for cultural purposes.[3] The restoration was undertaken by the Maltese architect Richard England.[10]

Throughout the course of renovation, St James has been transformed from an edifice designed to prohibit entry to one which welcomes visitors. England described the task of making this change as "making it possible for the building to accommodate new needs in a way that, while respecting the past, accepts the concept of change, without fear." However, the work was the cause of much controversy and was deemed unsatisfactory by many Maltese, partly resulting in the halting of other planned projects in Valletta and the decision to use celebrated architects (including Renzo Piano) rather than Richard England. The other projects started in 2008 when works commenced on the City Gate, the site of the former opera house, the new parliament building and the rest of the area around the city's entrance.

One of the biggest challenges that Prof. England faced was that of increasing accessibility in a building created to repel invaders. This necessitated major structural intervention and very difficult decisions about which areas should, and must, undergo such drastic intervention.

This task was carried off with great aplomb in the conversion of the two water cisterns, one into St James' spectacular theatre space and the other into the atrium. A stunning, unifying space which provides access to the upper galleries. the design nonetheless incorporate glass panels and a marvelous awareness of space that allows the visitor to read the historical narrative told by the wells.

The work was carried out in collaboration with the restoration expert Michael Ellul. With and emphasis that firmly discouraged the use of replica and imitation. Hence anything that looks 16th century is 16th century and anything that looks contemporary is contemporary. The national heritage organization Fondazzjoni Wirt Artna did protest against the removal of a rare World War Two gas shelter and other historical remains from the British period.

This theme is particularly obvious on the ground floor. In the Music Room, the British-installed ceiling has been removed, and the room restored to its original state. The gift shop, on the other hand, is split. In other halls partial removal of the ceiling has allowed both periods to be represented in this modern interpretation of a deeply historical building.

Restoration of the cavalier was complete by the end of summer 2000, and it opened to the public as St James Cavalier, Centre for Creativity on 22 September of that year, with an exhibition entitled Art in Malta Today.[3] The cavalier now houses a small theatre, a cinema, music rooms and art galleries. Various exhibitions and other cultural events are regularly held there. Since it was opened it has welcomed over a million visitors.[13] In August 2015, the cavalier was re-branded as Spazju Kreattiv (Maltese for Creative Space).[14] Its artistic director is Toni Sant.[15][16]

The cavalier is scheduled as a Grade 1 national monument, and it is also listed on the National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands.[17]

Architecture

St James Cavalier is a large casemated artillery platform having a pentagonal plan. The structure was not designed with aesthetics in mind, highlighting its purely utilitarian military function.[3] Despite the impression of size given by the external aspect of the building, half of the structure was filled with compressed earth and the rest consisted of series of sparse chambers and a ramp by which cannons could reach the roof.

The cavalier occupies the rear face of St James' Bastion, and it was meant to be able to fire over the bastion's main parapet, without interfering with its fire. A number of gunpowder magazines are located to the rear of the structure.[17]

Further reading

- St James Cavalier; Centre for Creativity in Malta. Book Distributors Limited. 2005. ISBN 88-87202-67-2.

- Rix, Juliet (2015). Malta and Gozo. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9781784770259.

References

- "History of Valletta". Valletta Local Council. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- David, Borg-Muscat (1933). "Reassessing the September 1775 Rebellion: A Case of Lay Participation or a 'Rising of the Priests'" (PDF). Melita Historica. 3 (2): 242, 256.

- "St James – A Short History". St James Cavalier. Archived from the original on 2004-10-13.

- Micallef, Martin. "St John's Cavalier". Maltese Association of the SMOM. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "A Brief History". salutingbattery.com. Fondazzjoni Wirt Artna. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- "One World – Protecting the most significant buildings, monuments and features of Valletta (44)". Times of Malta. 30 August 2008. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015.

- "Post Offices Opening Hours". MaltaPost. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015.

- Borg Muscat, David (2002). "Reassessing the September 1775 Rebellion: a Case of Lay Participation or a 'Rising of the Priests'?". Melita Historica. 13 (3): 239–252. Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Sciberras, Sandro. "Maltese History – E. The Decline of the Order of St John In the 18th Century" (PDF). St Benedict College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014.

- "About St James Cavalier". Fondazzjoni Kreattività. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015.

- "Regimental Hospitals and Military Hospitals of the Malta Garrison". maltarmc.com. British Army Medical Services And the Malta Garrison 1799 – 1979. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- Cordina, John (19 April 2013). "Government Printing Press to be strengthened". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- "St.James Cavalier Theatre Overview in Valletta, Malta". Island of Gozo. Gozo Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "New phase for St James Cavalier rebranding process". Times of Malta. 30 August 2015. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015.

- "New artistic directors announced". Valeetta. 3 November 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Reljic, Teodor (8 December 2014). "Ringing in the changes: Toni Sant". Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "St James Cavalier – Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. James Cavalier. |