Royal Palace of Madrid

The Royal Palace of Madrid (Spanish: Palacio Real de Madrid) is the official residence of the Spanish royal family at the city of Madrid, although now used only for state ceremonies. The palace has 135,000 square metres (1,450,000 sq ft) of floor space and contains 3,418 rooms.[1][2] It is the largest functioning royal palace and the largest by floor area in Europe.[3]

| Royal Palace of Madrid | |

|---|---|

Palacio Real de Madrid | |

Royal Palace of Madrid | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Baroque, Classicism |

| Town or city | Madrid |

| Country | Spain |

| Coordinates | 40.417974°N 3.714302°W |

| Construction started | April 7, 1735 |

| Client | King Felipe V of Spain |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 135,000 m2 (1,450,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Filippo Juvarra (first of many) |

| Official name | Palacio Real de Madrid |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1931 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001061 |

King Felipe VI and the royal family do not reside in the palace, choosing instead the significantly more modest Palace of Zarzuela on the outskirts of Madrid. The palace is now open to the public, except during state functions, although it is so large that only a selection of the best rooms are on the visitor route at any one time, the route being changed every few months. An admission fee of €13 is charged; however, at some times it is free. The palace is owned by the Spanish state and administered by the Patrimonio Nacional, a public agency of the Ministry of the Presidency.[4] The palace is on Calle de Bailén ("Bailén Street") in the western part of downtown Madrid, east of the Manzanares River, and is accessible from the Ópera metro station.

The palace is on the site of a 9th-century Moorish Alcázar, near the town of Magerit, constructed as an outpost by Muhammad I of Córdoba[5] and inherited after 1036 by the independent Moorish Taifa of Toledo. After Madrid fell to King Alfonso VI of Castile in 1083, the edifice was only rarely used by the kings of Castile. In 1329, King Alfonso XI of Castile convened the Cortes of Madrid for the first time. King Felipe II moved his court to Madrid in 1561.

The Castilian Alcázar was on the site, mostly built in the 16th century. After it burned down on 24 December 1734, King Felipe V ordered a new palace built on the same site. Construction spanned the years 1738 to 1755[6] and followed a Berniniesque design by Filippo Juvarra and Giovanni Battista Sacchetti in cooperation with Ventura Rodríguez, Francesco Sabatini, and Martín Sarmiento. King Carlos III first occupied the new palace in 1764.

The last monarch who lived continuously in the palace was King Alfonso XIII, although Manuel Azaña, president of the Second Republic, also inhabited it, making him the last head of state to do so. During that period the palace was known as "Palacio Nacional". There is still a room next to the Real Capilla, which is known by the name "Office of Azaña".

The interior of the palace is notable for its wealth of art and the use of many types of fine materials in the construction and the decoration of its rooms. It includes paintings by artists such as Caravaggio, Juan de Flandes, Francisco de Goya, and Velázquez, and frescoes by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Corrado Giaquinto, and Anton Raphael Mengs. Other collections of great historical and artistic importance preserved in the building include the Royal Armoury of Madrid, porcelain, watches, furniture, silverware, and the world's only complete Stradivarius string quintet.

History of the building

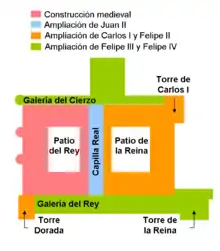

The palace was initially built by Muhammad I, Umayyad Emir of Cordoba, between 860 and 880. After the Moors were driven out of Toledo in the 11th century, the castle retained its defensive function. Henry III of Castile added several towers. His son John II used it as a royal residence.[5] During the War of the Castilian Succession (1476) the troops of Joanna la Beltraneja were besieged in the Alcázar, during which the building suffered severe damage.

The only drawing of the castle from the Middle Ages is one from 1534 by Cornelius Vermeyen.[5]

Emperor Charles V, with the architects Alonso de Covarrubias and Luis de Vega, extended and renovated the castle in 1537. Philip II made Madrid his capital in 1561 and continued the renovations, with new additions. Philip III added a long southern facade between 1610 and 1636.

Philip V of Bourbon renovated the royal apartments in 1700.[7] The Alcázar of the Habsburgs was austere in comparison to the Palace of Versailles where the new king had spent his childhood; and he began a series of redesigns mainly planned by Teodoro Ardemans and René Carlier, with the main rooms being redecorated by Queen Maria Luisa of Savoy and the Princess of Ursins in the style of French palaces.

The baroque palace

On Christmas Eve 1734, the Alcázar was destroyed by a fire that originated in the rooms of the French painter Jean Ranc. Response to the fire was delayed due to the warning bells being confused with the call to mass. For fear of looting, the doors of the building remained closed, hampering rescue efforts. Many works of art were lost, such as the Expulsion of the Moors, by Diego Velázquez. Others, such as Las Meninas, were rescued by tossing them out the windows. Fortunately, many pieces were saved because shortly before the blaze the king ordered that much of his collection be moved to the Buen Retiro Palace. This fire lasted four days and completely destroyed the old Alcázar, whose remaining walls were finally demolished in 1738.

Italian architect Filippo Juvarra oversaw work on the new palace and devised a lavish project of enormous proportions inspired by Bernini's plans for the Louvre. This plan was not realized, due to Juvarra's untimely death in March 1736.[9] His disciple Giambattista Sacchetti, also known as Juan Bautista Sacchetti or Giovanni Battista Sacchetti,[10] was chosen to continue the work of his mentor. Sacchetti designed the structure to encompass a large square courtyard and resolved sightline problems by creating projecting wings.

In 1760, Charles III called upon Sicilian Francesco Sabatini,[11] a Neoclassical architect, to enlarge the building. Sabatini's original idea was to frame the Plaza de la Armería with a series of galleries and arcades, to accommodate various dependencies, by constructing two wings along the square. Only the extension of the southeast tower known as la de San Gil was completed. Sabatini also planned to extend the north side with a large wing that echoed the style of the main building and included three square courtyards that would be smaller than the large central courtyard. Work on this expansion started quickly but was soon interrupted, leaving the foundations buried under a platform on which the royal stables were later built. The stables were demolished in the 20th century and replaced by the Sabatini Gardens. Charles III first occupied the palace in 1764.

In the 19th century, Ferdinand VII, who spent many years imprisoned in the Château de Valençay, began the most thorough renovation of the palace. The aim of this redesign was to turn the old-fashioned Italian-style building into a modern French-style palace. However, his grandson Alfonso XII proposed to turn the palace into a Victorian-style residence. Alfonso's plans were designed by the architect José Segundo de Lema and consisted of remodeling several rooms, replacing marble floors with parquet, and adding period furniture.

In the twentieth century, restoration work was needed to repair damage suffered during the Spanish Civil War, by repairing or reinstalling decoration and decorative trim and replacing damaged walls with faithful reproductions of the originals.

Exterior

The main facade of the Palace, the one facing the Plaza de la Armeria, consists of a two-story rusticated stone base, from which rise Ionic columns on Tuscan pilasters framing the windows of the three main floors. The upper story is hidden behind a cornice which encircles the building and is capped with a large balustrade. This was adorned with a series of statues of saints and kings, but these were relocated elsewhere under the reign of Charles III to give the building a more classical appearance.[12]

The restoration of the facade in 1973, which includes Sabitini's balcony of four Doric columns, returned some of Sachetti's sculptures. These include statues of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II and the Inca emperor Atahualpa, works by Juan Pascual de Mena and Domingo Martínez, respectively. Representations of the Roman emperors Honorius, Theodosius I, and Arcadius by G.D. Olivieri, and Trajan by Felipe de Castro were placed in the Prince's courtyard. Flanking Sabatini's clock the Statues of Philip V, Ferdinand VI, Barbara of Braganza and Maria Luisa of Savoy interspersed with The Rising Sun Following the Zodiac. Above the clock is the royal coat of arms flanked by angels, and, above that, bells that date from 1637 and 1761.[13][14]

Plaza de la Armería

The square as it exists now was laid-out in 1892, according to a plan by the architect Enrique María Repullés. However, the history of this square dates back to 1553, the year in which Philip II ordered a building to house the royal stables.

The Almudena Cathedral faces the palace across the plaza. Its exterior is neo-classical to match its surroundings while its interior is neo-gothic. Construction was funded by King Alfonso XII to house the remains of his wife Mercedes of Orléans.[15] Construction of the church began in 1878 and concluded in 1992.

Narciso Pascual Colomer, the same architect who crafted the Plaza de Oriente, designed the layout of the plaza in 1879, but failed to materialize. The site now occupied by the Plaza de la Armería was used for many decades as anteplaza de armas. Sachetti tried to build a cathedral to finish the cornice of the Manzanares, and Sabatini proposed to unite this building with the royal palace, to form a single block. Both projects were ignored by Charles III.

Ángel Fernández de los Ríos in 1868 proposed the creation of a large wooded area that would travel all around the Plaza de Oriente, in order to give a better view of the Royal Palace. A decade later Segundo de Lema added a staircase to the original design of Fernández, which led to the idea of Francisco de Cubas to give more importance to the emerging church of Almudena.

Plaza de Oriente

The Plaza de Oriente is a rectangular park that connects the east facade of Palacio Real to the Teatro Real. The eastern side of plaza is curved and bordered by several cafes in the adjoining buildings. Although the plaza was part of Sacchetti's plan for the palace, construction did not begin until 1808 when King Joseph Bonaparte, who ordered the demolition of approximately 60 medieval structures, that included a church, monastery and royal library, located on the site. Joseph was deposed before construction was completed, it was finished by Queen Isabella II who tasked architect Narciso Pascual Colomer with creating the final design in 1844.[16][17]

_11.jpg.webp)

Pathways divide the Plaza into three main plots: the Central Gardens, the Cabo Noval Gardens and the Lepanto Gardens. The Central Gardens are arranged in a grid around the central monument to Philip IV, following the Baroque model garden. They consist of seven flowerbeds, each bordered with box hedges and holding small cypress, yew and magnolias and annual flowers. The north and south boundaries of the Central Gardens are marked by a row of statues, popularly known as the Gothic kings— sculptures representing five Visigoth rulers and fifteen rulers of the early Christian kingdoms in the Reconquista. They are carved from limestone, and are part of a series dedicated to all monarchs of Spain. These were ordered for the decoration of the Palacio Real and were executed between 1750 and 1753. Engineers felt the statues were too heavy for the palace balustrade, so they were left on ground level where their lack of fine detail is readily apparent. The remainder of the statues are in the Sabatini Gardens.[18][19]

Isabel II laid out the grounds so that Pietro Tacca's equestrian statue of Philip IV was placed in the center, opposite the Prince's Gate.[20]

Campo del Moro Gardens

These gardens are so named because the Muslim leader Ali ben Yusuf allegedly camped here with his troops in 1109 during an attempted reconquest of Madrid. The first improvements to the area occurred under King Philip IV, who built fountains and planted various types of vegetation, but its overall look remained largely neglected. During the construction of the palace various landscaping projects were put forth based on the gardens of the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso, but lack of funds hampered further improvement until the reign of Isabel II who began work in earnest. Following the taste of the times, the park was designed in the Romanticist style.

The Triton fountain from the Islet Garden of Aranjuez and the Fountain of the Shells from the Palace of the Infante Luis at Boadilla del Monte were aligned in the center of the right angled pathways by Isabel II, according to plans by Narciso Pascual Colomer. Under the regency of Maria Christina of Austria, the park was reformed according to Ramon Oliva's romanticism plans. Between the Fountain of Tritons and the palace is The Large Cavern or Grotto (Camellia House), built by Juan de Villanueva during the reign of Joseph Bonaparte. Sacchetti's 1757-1758 Little Cavern or Grotto (Potato Room) is in front of the Parade Ground.[21][22]

Sabatini Gardens

.jpg.webp)

The Sabatini Gardens adjoin the north side of the Palacio real and extend to the calle de Bailén and the cuesta de San Vicente. The garden follows the symmetrical French design and work began in 1933, under the Republican government. Although they were designed by Zaragozan architect Fernando García Mercadal, they were named for Francesco Sabatini who designed the royal stables that previously occupied this site. These gardens feature a large rectangular pond which is surrounded by four fountains and statues of Spanish kings which were originally intended to crown the Royal Palace. Geometrically sited between its rides, there are several fountains.[23]

The Republican government constructed the gardens to return the area from control of the royal family to the people, the public was not allowed in the gardens until 1978 when they were opened by King Juan Carlos I.[24]

Interior of the palace

Grand Staircase

Built by Sabatini in 1789 when Charles IV wanted it moved to the opposite side of where Sabatini placed it in 1760, it is composed of a single piece of San Agustin marble. Two lions grace the landing, one by Felipe de Castro and another by Robert Michel. The frescoes on the ceiling is by Corrado Giaquinto and depicts Religion Protected by Spain.[25] On the ground floor is a statue of Charles III in Roman toga, with a similar statue on the first floor depicting Charles IV. The four cartouches at the corners depict the elements of water, earth, air and fire.[26]

Royal Library

The Royal Library was moved to the lower floor during the regency of Maria Christina. The bookshelves date from the period of Charles III, Isabel II and Alfonso XII.[27]

Highlights of the collection include the Book of hours of Isabella I of Castile, a codex of the time of Alfonso XI of Castile, a Bible of Doña María de Molina and the Fiestas reales, dedicated to Ferdinand VI by Farinelli. Also important are the maps kept in the library, which analyze the extent of the kingdoms under the Spanish Empire. Also on display a selection of the best medals from the Royal Collection.

The bookcovers demonstrate evolution of binding styles by era. Examples in the holdings include Rococo in gold with iron lace, Neoclassical in polychrome and Romantic with Gothic and Renaissance motifs.

The Archives of the Royal Palace contains approximately twenty thousand articles ranging from the Disastrous decade (1823-1833) to the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931. In addition, it holds some scores of musicians of the Royal Chapel, privileges of various kings, the founding order of the Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, the testament of Philip II and correspondence of most of the kings of the House of Bourbon.

Royal Pharmacy

During the reign of Felipe II the Royal Pharmacy became an appendage of the royal household and ordered the supply of medicines, a role that continues today.

The collection includes jars made by La Granja de San Ildefonso, 19th century, and Talavera de la Reina pottery, 18th century.[28]

Royal Armory

Along with the Imperial Armoury of Vienna, the armory is considered one of the best in the world and consists of pieces as early as the 13th century. The building, designed by J.S. de Lema and E. Repulles, was opened in 1897[29]

The collection highlights the tournament pieces made for Charles V and Philip II by the leading armourers of Milan and Augsburg. Among the most remarkable works are full armour and weapons that Emperor Charles V used in the Battle of Mühlberg, and which was portrayed by Titian in his famous equestrian portrait housed at the Museo del Prado. Unfortunately, parts of the collection were lost during the Peninsular War and during the Spanish Civil War.

Still, the armoury retains some of the most important pieces of this art in Europe and the world, including a shield and burgonet by Francesco and Filippo Negroli, one of the most famous designers in the armourers' guild.[30]

King Charles III's Apartments

The Halberdier's Room, or Guard Room, was designed by Sabatini, and includes the fresco by Tiepolo, Venus and Vulcan. Two paintings by Luca Giordano depict scenes from the life of Solomon.[31][32]

The Hall of Columns has a ceiling fresco by Giaquinto, representing The Sun before Which All the Forces of Nature Awaken and Rejoice, an allegory of the king as Apollo. An 1878 bronze statue of Charles V Vanquishing Fury is by Ferdinand Barbedienne. The bronze chandeliers were made in Paris in 1846, and installed by Isbella II for her balls.[33][34]

The Throne Room dates from Charles III in 1772, and features Tiepolo's ceiling fresco, The Apotheosis of the Spanish Monarchy. Bronze sculptures include the Four Cardinal Virtues, four of the Seven Planets, Satyr, Germanicus, and four Medici lions flanking the dual throne.[35][36]

Charles III's Anteroom (Saleta) contains a 1774 ceiling fresco Apotheosis of Trajan by A.R. Mengs. The Antechamber of Charles III (The Conversation Room) also contains a ceiling fresco by Mengs, The Apotheosis of Hercules. This room has four royal family portraits by Goya.[37][38]

The Queen's apartments and banqueting hall

Formerly the queen's apartments under Charles III, the three rooms were converted into a banquet hall by Alfonso XII in 1879, and completed in 1885. The three ceiling frescoes remained though, Dawn in Her Chariot by Raphael Mengs, Christopher Columbus Offering the New World to the Catholic Monarchs by Alejandro González Velázquez, and Boabdil Giving the Keys to Granada to the Catholic Monarchs by Francisco Bayeu y Subías.[39][40]

Apartments of Infante Luis

These rooms were formerly occupied by Infante Luis, Count of Chinchón before his exile. The Stradivarius Room now contains a viola, two viloncello, and two violins by Stradivari. The ceiling fresco by A. G. Velazquez, depicts Gentleness accompanied by the Four Cardinal Virtues.[41]

The Chamber of the Infante Luis, Musical Instruments Room, has a ceiling fresco by Francisco Bayeu depicting Providence Presiding over the Virtues and Faculties of Man.[42]

Royal Chapel

Designed in 1748 by Sacchetti and Ventura Rodríguez, the chapel features ceiling frescoes by Giaquinto, including The Trinity, Allegory of Religion, Glory and the Holy Trinity Crowning the Virgin. Above the High Altar is Ramon Bayeu's St. Michael. The reliquary altar has Ercole Ferrata's 1659 silver relief Pope Leo I Stopping Attila at the Gates of Rome.[43][44]

The Crown Room

Formerly the apartment of Alfonso XIII's mother, Maria Christina of Austria, the room contains Charles III's throne, scepter and crown. Tapestries from Jacopo Amigoni's Four Seasons adorn the walls. Also of note are the abdication speech of Juan Carlos I and the proclamation speech of Felipe VI.[45]

Gallery

The Gasparini Room, Royal Palace, Madrid, Spain, 1927

The Gasparini Room, Royal Palace, Madrid, Spain, 1927 The Porcelain Room, Royal Palace, Madrid, 1927

The Porcelain Room, Royal Palace, Madrid, 1927 Salon of Charles III, Royal Palace, Madrid, 1927

Salon of Charles III, Royal Palace, Madrid, 1927 Spanish Royal Crown and Scepter

Spanish Royal Crown and Scepter

Today

The wedding banquet of Prince Felipe and Letizia Ortiz took place on 22 May 2004 in the central courtyard of the palace.

See also

- Project of Filippo Juvarra for the Royal Palace of Madrid

- Palacio del Buen Retiro (another royal palace in Madrid, now mostly demolished)

- Royal Palace of El Pardo

- Royal Palace of Aranjuez

- Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso

- Royal Palace of La Almudaina

Further reading

- García‐Zúñiga, Mario; Losa, Ernesto López. 2021. "Skills and human capital in eighteenth-century Spain: wages and working lives in the construction of the Royal Palace of Madrid (1737–1805)". The Economic History Review.

References

- "Palacio Real". Cyberspain.com. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "What is the biggest palace in Europe?". Ask Yahoo!. Yahoo! Inc. 28 April 2004. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Petr H. (2017). "25 Largest Palaces In The World". List 25. p. 4. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- Sancho 2014, p. 7.

- Viso 2014, p. 7.

- "Palacio Real de Madrid". Patrimonio Nacional (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- Viso 2014, p. 7-8.

- Brambalia, Fernando. "Vista de parte del Real Palacio tomada de la cuesta de la Vega" [View of part of the Royal Palace taken from la Cuesta de la Vega]. Spain Ministry of Economy and Public Administrations (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Viso 2014, p. 8.

- Autonomous University of Madrid (6 May 2003). "Calle del Arenal 13". Madrid Histórico (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Viso 2014, p. 9.

- Sancho 2014, p. 18.

- Sancho 2014, p. 18-20.

- Viso 2014, p. 14-15.

- "Catedral de Santa María la Real de la Almudena". GoMadrid.com. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- "Plaza de Oriente". GoMadrid.com. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- "Plaza de Oriente, Madrid". Madrid-Tourist.com. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- Álvarez Rodríguez, Miguel (2003). Memoria monumental de Madrid: guía de estatuas y bustos. La Liberia. ISBN 84-95889-61-7.

- Salvador Prieto, María del Socorro (1990). Escultura monumental en Madrid: calles, plazas y jardines públicos (1875–1936). Alpuerto. ISBN 84-381-0147-X.

- Sancho 2014, p. 82.

- Sancho 2014, p. 82-83.

- Viso 2014, p. 60-63.

- Slavito (5 February 2008). "Sabatini Gardens: Chilling With the Kings". Sitebits.com. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- "Jardines de Sabatini". Madrid-Tourist.com. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- Sancho 2014, p. 24.

- Viso 2014, p. 30.

- Sancho 2014, p. 77.

- Sancho 2014, p. 78.

- Viso 2014, p. 54.

- Viso 2014, p. 56-57.

- Sancho 2014, p. 26-28.

- Viso 2014, p. 32-33.

- Sancho 2014, p. 28-31.

- Viso 2014, p. 34-35.

- Sancho 2014, p. 34-40.

- Viso 2014, p. 50-53.

- Sancho 2014, p. 40-47.

- Viso 2014, p. 36-37.

- Sancho 2014, p. 56-59.

- Viso 2014, p. 44-45.

- Sancho 2014, p. 62-63.

- Sancho 2014, p. 62-64.

- Sancho 2014, p. 67-70.

- Viso 2014, p. 46-47.

- Viso 2014, p. 48-49.

Bibliography

- Sancho, J.L. (2014). Guide Palacio Real de Madrid. Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional. ISBN 9788471202949.

- Viso, E.E. (2014). The Royal Palace Madrid. Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional. ISBN 9782758005896.