Peromyscus maniculatus

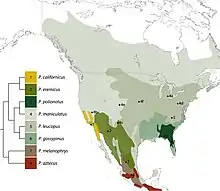

Peromyscus maniculatus is a rodent native to North America. It is most commonly called the deer mouse, although that name is common to most species of Peromyscus, and thus is often called the North American deermouse[2] and is fairly widespread across the continent, with the major exception being the southeast United States and the far north.

| Peromyscus maniculatus | |

|---|---|

_(9310532204).jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Neotominae |

| Genus: | Peromyscus |

| Species: | P. maniculatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Peromyscus maniculatus (Wagner, 1845) | |

Like other Peromyscus species, it can be a vector and carrier of emerging infectious diseases such as hantaviruses and Lyme disease.[3][4]

It is closely related to Peromyscus leucopus, the white-footed mouse.

Overview

The species has 61 subspecies.[5] They are all tiny mammals that are plentiful in number.[6] The deer mouse is a small rodent that lives in the Americas and is closely related to the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus.[7] Because the two species are extremely similar in appearance, they are best distinguished through red blood cell agglutination tests or karyotype techniques. The deer mouse can also be distinguished physically by its long and multicolored tail.[8] Deer mice are very often used for laboratory experimentation due to their self cleanliness and easy care.[7]

Physical description

The deer mouse is small in size, only 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 cm) long, not including the tail. They have large beady eyes and large ears giving them good sight and hearing. Peromyscus maniculatus has soft fur which varies in color, from gray to brown, but all deer mice have a distinguishable white underside and white feet. Deer mice tails are covered with fine hairs, with the same dark/light split as the fur on the rest of its body.[9] P. maniculatus has distinct subspecies. Of those most common in North America, the woodland form has longer hind legs, a longer tail, and larger ears than the prairie form. [5]

Behavior

Deer mice are nocturnal creatures who spend the day time in areas such as trees or burrows where they have nests made of plant material.[7] The pups within litters of deer mice are kept by the mother within an individual home range. Deer Mice typically live in a home range of 242 to 3000 square meters. Although deer mice live in individual home ranges, these ranges do tend to overlap. When overlapping occurs, it is more likely to be with opposite sexes rather than with the same sex, as male deer mice have a much greater home range than the much more territorial females. Deer mice that live within overlapping home ranges tend to recognize one another and interact a lot.[10]

The woodland variety of P. maniculatus is an adept climber, and prefers tree cover meters above the ground, while the prairie form prefers to move from burrow to burrow in open areas, avoiding floral cover.[5]

Reproduction and life span

Procreation

Peromyscus manicuatus are polygynous, meaning one male will mate with multiple females. They exhibit behaviors associated with polygyny, as males have much larger territory than females, live with multiple females, and are known to commit infanticide if they catch young unattended. Though they usually live alone, during winter the single male-multiple female cohort may live in a shared nest. [11]

Breeding season

Deer mice can reproduce throughout the year, though in most parts of their range, they breed from March to October.[12] Deer mouse breeding tends to be determined more by food availability rather than by season. In Plumas County, California, deer mice bred through December in good mast (both soft and hard masts) years but ceased breeding in June of a poor mast year.[13] Deer mice breed throughout the year in the Willamette Valley, but in other areas on the Oregon coast there is usually a lull during the wettest and coldest weather.[14] In southeastern Arizona at least one-third of captured deer mice were in breeding condition in winter.[15] In Virginia breeding peaks occur from April to June and from September to October.[16]

Nesting

Female deer mice construct nests using a variety of materials including grasses, roots, mosses, wool, thistledown, and various artificial fibers.[14] The male deer mice are allowed by the female to help nest the litter and keep them together and warm for survival.[17]

In a study, less than half of both male and female deer mice left their original home range to reproduce. This means that there is intrafamilial mating and that the gene flow among deer mice as a whole is limited.[18]

There have been recent studies that reveal deer mice also have OCD-like behaviors from altered gut microbiota. This phenomenon is typically shown in their abnormally large nest sizes and the behavior is present within 8 weeks of birth. Large nest building is considered to be a maladaptation as these mice are unnecessarily investing extra energy and effort in building larger nests in a laboratory where conditions are stable.[19]

Gestation, litter size and productivity

Deer mice reproduce profusely and are highest in numbers among their species compared to other local mammals. Peromyscus species' gestation periods range from 22 to 26 days.[20] Typical litters are composed of three to five young;[7] litter size ranges from one to nine young. Most female deer mice have more than one litter per year.[14] Three or four litters per year is probably typical; captive deer mice have borne as many as 14 litters in one year. Males usually live with the family and help care for the young.[12]

Development of young

Deer mice pups are altricial, i.e. born blind, naked and helpless; development is rapid. Young deer mice have full coats by the end of the second week; their eyes open between 13 and 19 days and they are fully furred and independent in only a few weeks.[14] Females lactate for 27 to 34 days after giving birth; most young are weaned at about 18 to 24 days. The young reach adult size at about 6 weeks and continue to gain weight slowly thereafter.[20]

Age of first estrus averages about 48 days; the earliest recorded was 23 days. The youngest wild female to produce a litter was 55 days old; it was estimated that conception had occurred when she was about 32 days old.[20]

Dispersal

Deer mouse pups usually disperse after weaning and before the birth of the next litter, when they are reaching sexual maturity. Occasionally juveniles remain in the natal area, particularly when breeding space is limited.[21] Most deer mice travel less than 152 m (499 ft) from the natal area to establish their own home range.[22]

Longevity and mortality

In the lab their maximum life span is 96 months, and mean life expectancy is 45.5 months for females and 47.5 for males.[23] In many areas deer mice live less than 1 year.[14] O'Farrell reported that a population of deer mice in big sagebrush/grasslands had completely turned over (e.g., there were no surviving adults of the initial population) over the course of one summer.[24] One captive male deer mouse lived 32 months,[14] and there is a report of a forest deer mouse that lived 8 years in captivity (another mouse was fertile until almost 6 years of age).[25]

Habitat

Peromyscus maniculatus are found in all throughout North America.[7] The majority of deer mice nest high up, in large hollow trees. The deer mouse nests alone for the most part but during the winter will nest in groups of 10 or more.[26] They are populous in the western mountains and live in wooded areas and areas that were previously wooded.[6] Deer mice, specifically the prairie form, are also abundant in the farmland of the midwestern United States.[5] Deer mice can be found active on top of snow or beneath logs during the winter seasons.[17]

Deer mice inhabit a wide variety of plant communities including grasslands, brushy areas, woodlands, and forests.[27] In a survey of small mammals on 29 sites in subalpine forests in Colorado and Wyoming, the deer mouse had the highest frequency of occurrence; however, it was not always the most abundant small mammal.[28] Deer mice were trapped in four of six forest communities in eastern Washington and northern Idaho, and they were the only rodent in ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) savanna.[29] In northern New England deer mice are present in both coniferous and deciduous forests.[30] Deer mice are often the only Peromyscus species in northern boreal forest.[13] Subspecies differ in their use of plant communities and vegetation structures. There are two main groups of deer mouse: the prairie deer mouse and the woodland or forest deer mouse group.[27]

Cover requirements

Deer mice are often active in open habitat; most subspecies do not develop hidden runways the way many voles (Microtus and Clethrionomys spp.) do.[13][31] In open habitat within forests deer mice have a tendency to visit the nearest timber.[32] In central Ontario deer mice used downed wood for runways.[33]

Deer mice nest in burrows dug in the ground or construct nests in raised areas such as brush piles, logs, rocks, stumps, under bark, and in hollows in trees.[14][27][33] Nests are also constructed in various structures and artifacts including old boards and abandoned vehicles. Nests have been found up to 24 m (79 ft) above the ground in Douglas-fir trees.[14]

Predators

Deer mice are important prey for snakes (Viperidae), owls (Strigidae), minks (Neovison vison), martens (Martes americana) and other mustelids, as well as skunks (Mephites and Spilogale spp.), bobcats (Lynx rufus), domestic cats (Felis catus), coyotes (Canis latrans), foxes (Vulpes and Urocyon spp.), and ringtail cats (Bassariscus astutus).[14] Deer mice are also parasitized by Cuterebra fontinella. [34]

Diet

Deer mice are omnivorous; the main dietary items usually include seeds, fruits, arthropods, leaves, and fungi; fungi have the least amount of intake. Throughout the year, the deer mouse will change its eating habits to reflect on what is available to eat during that season. During winter months, the arthropods compose of one-fifth of the deer mouse's food. These include spiders, caterpillars, and heteropterans. During the spring months, seeds become available to eat, along with insects, which are consumed in large quantities. Leaves are also found in the stomachs of deer mice in the spring seasons. During summer months, the mouse consumes seeds and fruits. During the fall season, the deer mouse will slowly change its eating habits to resemble the winter's diet.[6]

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Agriculture document: "Peromyscus maniculatus".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Agriculture document: "Peromyscus maniculatus".

- Cassola, F. (2016). Peromyscus maniculatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T16672A22360898.en

- Bowers, Nora; Rick Bowers; and Kenn Kaufman (2004). Kaufman Guide to North American Mammals. NY: Houghton-Mifflin Co. p.176.

- Netski, Dale; Brandonlyn Thran & Stephen St. Jeor (1999). "Sin Nombre Virus Pathogenesis in Peromyscus maniculatus". Journal of Virology. 73 (1): 585–591. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.1.585-591.1999. PMC 103864. PMID 9847363.

- Crossland, J. & Lewandowski, A. (2006). "Peromyscus – A fascinating laboratory animal model" (PDF). Techtalk. 11 (1–2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2008.

- "Peromycus maniculatus Deer Mouse | Peromyscus Genetic Stock Center | University of South Carolina". www.pgsc.cas.sc.edu. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Jameson, E W (1952). "Food of Deer Mice, Peromyscus maniculatus and P. boylei, in the Northern Sierra Nevada, California". Journal of Mammalogy. 33 (1): 50–60. doi:10.2307/1375640. JSTOR 1375640.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. (Vol. 12, p. 631). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Tessier, Nathalie; Sarah Noel & Francois Lapointe (2004). "A new method to discriminate the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) from the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) using species-specific primers in multiplex PCR". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (11): 1832–35. doi:10.1139/z04-173.

- "LTER (Sevilleta Long-Term Ecological Research Project)". University of New Mexico. 1998.

- Dewsbury, Donald (1988). "Kinship, Familiarity, Aggression, and Dominance in Deer Mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) in Seminatural Enclosures". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 102 (2): 124–8. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.102.2.124. PMID 3165063.

- Advances in the study of Peromyscus (Rodentia). Kirkland, Gordon L., Layne, James Nathaniel. Lubbock, Tex., USA: Texas Tech University Press. 1989. ISBN 0-89672-170-1. OCLC 19222284.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Nowak, Ronald M.; Paradiso, John L. (1983). Walker's mammals of the world. 4th edition. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Baker, Rollin H. (1968). "Habitats and distribution". In: King, John Arthur, ed. Biology of Peromyscus (Rodentia). Special Publication No. 2. Stillwater, OK: The American Society of Mammalogists 98–126.

- Maser, Chris; Mate, Bruce R.; Franklin, Jerry F.; Dyrness, C. T. (1981). Natural history of Oregon Coast mammals. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-133. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station.

- Brown, J. H.; Zeng, Z. (1989). "Comparative Population Ecology of Eleven Species of Rodents in the Chihuahuan Desert". Ecology. 70 (5): 1507–1525. doi:10.2307/1938209. JSTOR 1938209.

- Wolff, Jerry O. (1994). "Reproductive success of solitarily and communally nesting white-footed mice and deer mice". Behavioral Ecology. 5 (2): 206–209. doi:10.1093/beheco/5.2.206.

- Hanney, Peter W. (1975) Rodents: Their Lives and Habits. New York: Taplinger Publishing Company.

- Wolff, Jerry & Deborah Durr (1986). "Winter Nesting Behavior of Peromyscus leucopus and Peromyscus maniculatus". Journal of Mammalogy. 67 (2): 409–12. doi:10.2307/1380900. JSTOR 1380900.

- Scheepers, Isabella M.; Cryan, John F.; Bastiaanssen, Thomaz F. S.; Rea, Kieran; Clarke, Gerard; Jaspan, Heather B.; Harvey, Brian H.; Hemmings, Sian M. J.; Santana, Leonard; Sluis, Rencia van der; Malan-Muller, Stefanie; Wolmarans, De Wet (2020). "Natural compulsive‐like behaviour in the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus bairdii) is associated with altered gut microbiota composition". European Journal of Neuroscience. 51 (6): 1419–1427. doi:10.1111/ejn.14610. PMID 31663195.

- Layne, JN (1966). "Postnatal development and growth of Peromyscus floridanus". Growth. 30 (1): 23–45. PMID 5959707.

- Walters, Bradley B (1991). "Small mammals in a subalpine old-growth forest and clearcuts". Northwest Science. 65 (1): 27–31. hdl:2376/1625.

- Stickel, Lucille F. (1968). Home range and travels. In: King, John Arthur, ed. Biology of Peromyscus (Rodentia). Special Publication No. 2. Stillwater, OK: The American Society of Mammalogists: 373–411

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (U.S.). Committee on Animal Models for Research on Aging; National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Animal Models for Research on Aging (1981). Mammalian models for research on aging. National Academies. ISBN 978-0-309-03094-6. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- O'Farrell, Michael J (1978). "Home range dynamics of rodents in a sagebrush community". Journal of Mammalogy. 59 (4): 657–668. doi:10.2307/1380131. JSTOR 1380131.

- Dice, Lee R. (1933). "Longevity in Peromyscus maniculatus gracilis". Journal of Mammalogy. 14: 147–148. doi:10.2307/1374020.

- Baker, Rollin H. (1983). Michigan Mammals. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press.

- Whitaker, John O., Jr. (1980). National Audubon Society field guide to North American mammals. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Raphael, Martin G. (1987). Nongame wildlife research in subalpine forests of the central Rocky Mountains. In: Management of subalpine forests: building on 50 years of research: Proceedings of a technical conference; 1987 July 6–9; Silver Creek, CO. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-149. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 113–122

- Hoffman, G. R. (1960). "The Small Mammal Components of Six Climax Plant Associations in Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho". Ecology. 41 (3): 571–572. doi:10.2307/1933338. JSTOR 1933338.

- Degraaf, Richard M.; Snyder, Dana P.; Hill, Barbara J. (1991). "Small mammal habitat associations in poletimber and sawtimber stands of four forest cover types". Forest Ecology and Management. 46 (3–4): 227–242. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(91)90234-M.

- Wagg, J. W. Bruce. (1964). White spruce regeneration on the Peace and Slave River lowlands. Publ. No. 1069. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Department of Forestry, Forest Research Branch

- Gashwiler, Jay S. (1959). "Small mammal study in west-central Oregon". Journal of Mammalogy. 40 (1): 128–139. doi:10.2307/1376123. JSTOR 1376123.

- Naylor, Brian J. (1994). "Managing wildlife habitat in red pine and white pine forests of central Ontario". Forestry Chronicle. 70 (4): 411–419. doi:10.5558/tfc70411-4.

- Cogley TP (1991). "Warble development by the rodent bot Cuterebra fontinella (Diptera: Cuterebridae) in the deer mouse". Veterinary Parasitology. 38 (4): 275–288. doi:10.1016/0304-4017(91)90140-Q. PMID 1882496.

External links

![]() Data related to Peromyscus maniculatus at Wikispecies

Data related to Peromyscus maniculatus at Wikispecies

- Description of species

- Additional description of species with photos

- Additional information on species

- Studying the homing ability of deer mice. (available on sci-hub).

- Information on hantaviruses, which can be carried by this species

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peromyscus maniculatus. |