Oxybenzone

Oxybenzone or benzophenone-3 or BP-3 (trade names Milestab 9, Eusolex 4360, Escalol 567, KAHSCREEN BZ-3) is an organic compound. It is a pale-yellow solid that is readily soluble in most organic solvents. Oxybenzone belongs to the class of aromatic ketones known as benzophenones. It is a naturally occurring[4] chemical found in various flowering plants[5] as well as being an organic component of many sunscreen lotions. It is also in widespread use in things like plastics, toys, furniture finishes, and more to limit UV degradation.[6]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2-Hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-phenylmethanone | |

| Other names

Oxybenzone Benzophenone-3 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.575 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C14H12O3 | |

| Molar mass | 228.247 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.20 g cm−3[2] |

| Melting point | 62 to 65 °C (144 to 149 °F; 335 to 338 K) |

| Boiling point | 224 to 227 °C (435 to 441 °F; 497 to 500 K) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 7.6 (H2O)[3] |

| Hazards[2] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 140.5 °C (284.9 °F; 413.6 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

>12800 mg/kg (oral in rats) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Structure and electronic structure

Being a conjugated molecule, oxybenzone absorbs light at lower energies than many aromatic molecules.[7] As in related compounds, the hydroxyl group is hydrogen bonded to the ketone.[8] This interaction contributes to oxybenzone's light-absorption properties. At low temperatures, however, it is possible to observe both the phosphorescence and the triplet-triplet absorption spectrum. At 175 K the triplet lifetime is 24 ns. The short lifetime has been attributed to a fast intramolecular hydrogen transfer between the oxygen of the C=O and the OH.[9]

Production

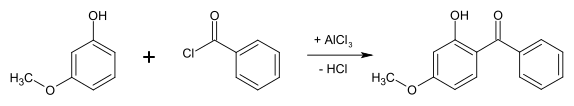

Oxybenzone is produced by Friedel-Crafts reaction of benzoyl chloride with 3-methoxyphenol.[10]

Uses

Oxybenzone is used in plastics as an ultraviolet light absorber and stabilizer.[10] It is used, along with other benzophenones, in sunscreens, hair sprays, and cosmetics because they help prevent potential damage from sunlight exposure. It is also found, in concentrations up to 1%, in nail polishes.[10] Oxybenzone can also be used as a photostabilizer for synthetic resins.[10] Benzophenones can leach from food packaging, and are widely used as photo-initiators to activate a chemical that dries ink faster.[11]

As a sunscreen, it provides broad-spectrum ultraviolet coverage, including UVB and short-wave UVA rays. As a photoprotective agent, it has an absorption profile spanning from 270 to 350 nm with absorption peaks at 288 and 350 nm.[12] It is one of the most widely used organic UVA filters in sunscreens today.[12] It is also found in nail polish, fragrances, hairspray, and cosmetics as a photostabilizer. Despite its photoprotective qualities, much controversy surrounds oxybenzone because of its possible hormonal and photoallergenic effects, leading many countries to regulate its use.

Safety

Some debate focuses on the potential of oxybenzone as a contact allergen[12] with a 2001 study finding contact dermatitis "uncommon" for oxybenzone.[13] Due to the advent of PABA-free sunscreens, oxybenzone is now the most common allergen found in sunscreens.[14][15][16][17]

In vivo studies

The incidence of oxybenzone causing photoallergy is extremely uncommon,[13] however, oxybenzone has been associated with rare allergic reactions triggered by sun exposure. In a study of 82 patients with photoallergic contact dermatitis, just over one quarter showed photoallergic reactions to oxybenzone.[18]

In a 2008 study of participants ages 6 and up, oxybenzone was detected in 96.8% of urine samples.[19] Humans can absorb anywhere from 0.4% to 8.7% of oxybenzone after one topical application of sunscreen, as measured in urine excretions. This number can increase after multiple applications over the same period of time.[20] Oxybenzone is particularly penetrative because it is the most lipophilic of the three most common UV filters.[21]

When applied topically, UV filters, such as oxybenzone, are absorbed through the skin, metabolized, and excreted primarily through the urine.[22] The method of biotransformation, the process by which a foreign compound is chemically transformed to form a metabolite, was determined by Okereke and colleagues through oral and dermal administration of oxybenzone to rats. The scientists analyzed blood, urine, feces, and tissue samples and found three metabolites: 2,4-dihydroxybenzophenone (DHB), 2,2-dihydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone (DHMB) and 2,3,4-trihydroxybenzophenone (THB).[23][24] To form DHB the methoxy functional group undergoes O-dealkylation; to form THB the same ring is hydroxylated.[22] Ring B in oxybenzone is hydroxylated to form DHMB.[22]

A study done in 2004 measured the levels of oxybenzone and its metabolites in urine. After topical application to human volunteers, results revealed that up to 1% of the applied dose was found in the urine.[25] The major metabolite detected was DHB and very small amounts of THB were found.[25] By utilizing the Ames test in Salmonella typhimurium strains, DHB was determined to be nonmutagenic.[26] In 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) noted in their recommendations for future study that, "While research indicates that some topical drugs can be absorbed into the body through the skin, this does not mean these drugs are unsafe."[27]

Effects on coral

Media reports link oxybenzone in sunscreens to coral bleaching,[28] although some environmental experts dispute the claim.[29] A small number of studies have been released which linked coral damage to oxybenzone exposure.[30][31] A 2015 study published in the Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology led to ban of oxybenxzone containing sunscreen in Palau.[32] However, the purported link between oxybenzone and coral decline is widely discussed within the environmental community since most studies on the subject have been conducted in a lab environment.[33] A 2019 study of UV filters in oceans found far lower concentrations of oxybenzone than previously reported, and lower than known thresholds for environmental toxicity.[34]

Health and environmental regulation

Australia

Revised as of 2007, the National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS) Cosmetic Guidelines allow oxybenzone for cosmetic use up to 10%.[35]

Canada

Revised as of 2012, Health Canada allows oxybenzone for cosmetic use up to 6%.[36]

European Union

The Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (SCCP) of the European Commission concluded in 2008 that it does not pose a significant risk to consumers, apart from contact allergenic potential.[37] It is allowed in sunscreens and cosmetics at levels of up to 6% and 0.5% respectively.[38]

Japan

Revised as of 2001, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare notification allows oxybenzone for cosmetic use up to 5%.[39]

Palau

The Palau government has signed a law that restricts the sale and use of sunscreen and skincare products that contain oxybenzone, and nine other chemicals. The ban comes into force in 2020.[40]

Sweden

The Swedish Research Council has determined that sunscreens with oxybenzone are unsuitable for use in young children, because children under the age of two years have not fully developed the enzymes that are believed to break it down. No regulations have come of this study yet.[10]

United States

Oxybenzone was approved for use in the US by the FDA in the early 1980s. Revised as of April 1, 2013, the FDA allows oxybenzone in OTC sunscreen products up to 6%.[41]

The Hawaii State Legislature has passed a bill that would prohibit the sale of non-prescription sunscreens containing oxybenzone and other chemicals that may be damaging to coral reefs (e.g. octyl methoxycinnamate), effective January 1, 2021.[42][43]

Key West has also banned the sale of sunscreens that contain the ingredients oxybenzone (and octinoxate). The ban goes into effect on January 1, 2021.[44] However, this legislation was superseded by the Florida State Legislature by Senate Bill 172.[45] Which prohibits local governments from regulating over-the-counter proprietary drugs and cosmetics (such as sunscreen containing oxybenzone and octinoxate). The statute became effective July 1, 2020.

The City of Miami Beach, Florida voted against a ban of oxybenzone, with commissioners citing public health concerns and lack of clarity on scientific evidence supporting such a ban.[46]

References

- Merck Index, 11th Edition, 6907

- 131-57-7 at commonchemistry.org

- Fontanals N, Cormack PA, Sherrington DC, Marcé RM, Borrull F (April 2010). "Weak anion-exchange hypercrosslinked sorbent in on-line solid-phase extraction-liquid chromatography coupling to achieve automated determination with an effective clean-up". Journal of Chromatography A. 1217 (17): 2855–61. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.064. PMID 20303088.

- "Benzophenone-3 (BP-3) Factsheet | National Biomonitoring Program | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-05-24. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- "Benzophenone-3 (BP-3) Factsheet". www.cdc.gov. 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- "Oxybenzone - Substance Information - ECHA". echa.europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- Castro GT, Blanco SE, Giordano OS (2000). "UV Spectral Properties of Benzophenone. Influence of Solvents and Substituents". Molecules. 5 (3): 424–425. doi:10.3390/50300424.

- Lago AF, Jimenez P, Herrero R, Dávalos JZ, Abboud JL (April 2008). "Thermochemistry and gas-phase ion energetics of 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy-benzophenone (oxybenzone)". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 112 (14): 3201–8. Bibcode:2008JPCA..112.3201L. doi:10.1021/jp7111999. PMID 18341312.

- Chrétien MN, Heafey E, Scaiano JC (2010). "Reducing adverse effects from UV sunscreens by zeolite encapsulation: comparison of oxybenzone in solution and in zeolites". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 86 (1): 153–61. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00644.x. PMID 19930122.

- "Hazardous Substances Data Bank". 2-HYDROXY-4-METHOXYBENZOPHENONE. National Library of Medicine (US), Division of Specialized Information Services. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Koivikko R, Pastorelli S, Rodríguez-Bernaldo de Quirós A, Paseiro-Cerrato R, Paseiro-Losada P, Simoneau C (October 2010). "Rapid multi-analyte quantification of benzophenone, 4-methylbenzophenone and related derivatives from paperboard food packaging" (PDF). Food Additives & Contaminants. Part A, Chemistry, Analysis, Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment. 27 (10): 1478–86. doi:10.1080/19440049.2010.502130. PMID 20640959. S2CID 8900382.

- Burnett ME, Wang SQ (April 2011). "Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 27 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00557.x. PMID 21392107.

- Darvay A, White IR, Rycroft RJ, Jones AB, Hawk JL, McFadden JP (October 2001). "Photoallergic contact dermatitis is uncommon". The British Journal of Dermatology. 145 (4): 597–601. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04458.x. PMID 11703286. S2CID 34414844.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF (2008). Fisher's Contact Dermatitis (6th ed.). Hamilton: PMPH-USA. p. 460. ISBN 9781550093780. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- DeLeo VA, Suarez SM, Maso MJ (November 1992). "Photoallergic contact dermatitis. Results of photopatch testing in New York, 1985 to 1990". Archives of Dermatology. 128 (11): 1513–8. doi:10.1001/archderm.1992.01680210091015. PMID 1444508.

- Scheuer E, Warshaw E (March 2006). "Sunscreen allergy: A review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and responsible allergens". Dermatitis. 17 (1): 3–11. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05017. PMID 16800271. S2CID 42168353.

- Zhang XM, Nakagawa M, Kawai K, Kawai K (January 1998). "Erythema-multiforme-like eruption following photoallergic contact dermatitis from oxybenzone". Contact Dermatitis. 38 (1): 43–4. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05637.x. PMID 9504247. S2CID 35237413.

- Rodríguez E, Valbuena MC, Rey M, Porras de Quintana L (August 2006). "Causal agents of photoallergic contact dermatitis diagnosed in the national institute of dermatology of Colombia". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 22 (4): 189–92. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2006.00212.x. PMID 16869867.

- Calafat AM, Wong LY, Ye X, Reidy JA, Needham LL (July 2008). "Concentrations of the sunscreen agent benzophenone-3 in residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003--2004". Environmental Health Perspectives. 116 (7): 893–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.11269. PMC 2453157. PMID 18629311.

- Gonzalez H, Farbrot A, Larkö O, Wennberg AM (February 2006). "Percutaneous absorption of the sunscreen benzophenone-3 after repeated whole-body applications, with and without ultraviolet irradiation". The British Journal of Dermatology. 154 (2): 337–40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07007.x. PMID 16433806. S2CID 1001823.

- Hanson KM, Gratton E, Bardeen CJ (October 2006). "Sunscreen enhancement of UV-induced reactive oxygen species in the skin". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 41 (8): 1205–12. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.011. PMID 17015167.

- Chisvert A, León-González Z, Tarazona I, Salvador A, Giokas D (November 2012). "An overview of the analytical methods for the determination of organic ultraviolet filters in biological fluids and tissues". Analytica Chimica Acta. 752: 11–29. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2012.08.051. PMID 23101648.

- Okereke CS, Kadry AM, Abdel-Rahman MS, Davis RA, Friedman MA (1993). "Metabolism of benzophenone-3 in rats". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 21 (5): 788–91. PMID 7902237.

- Okereke CS, Abdel-Rhaman MS, Friedman MA (August 1994). "Disposition of benzophenone-3 after dermal administration in male rats". Toxicology Letters. 73 (2): 113–22. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(94)90101-5. PMID 8048080.

- Sarveiya V, Risk S, Benson HA (April 2004). "Liquid chromatographic assay for common sunscreen agents: application to in vivo assessment of skin penetration and systemic absorption in human volunteers". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 803 (2): 225–31. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.12.022. PMID 15063329.

- "Hazardous Substances Data Bank". 2,4-Dihydroxybenzophenone. National Library of Medicine (US), Division of Specialized Information Services. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Office of the Commissioner (2019-05-09). "FDA finalizes recommendations for studying absorption of active ingredients in topically-applied OTC monograph drugs". FDA.

- Hughes T. "There's insufficient evidence your sunscreen harms coral reefs".

- Bogle A. "No, your sunscreen isn't killing the world's coral reefs". Mashable. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- Danovaro R, Bongiorni L, Corinaldesi C, Giovannelli D, Damiani E, Astolfi P, et al. (April 2008). "Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections". Environmental Health Perspectives. 116 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.10966. PMC 2291018. PMID 18414624.

- Downs CA, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, Fauth J, Knutson S, Bronstein O, et al. (February 2016). "Toxicopathological Effects of the Sunscreen UV Filter, Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3), on Coral Planulae and Cultured Primary Cells and Its Environmental Contamination in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 70 (2): 265–88. doi:10.1007/s00244-015-0227-7. PMID 26487337. S2CID 4243494.

- McGrath M (November 2018). "Coral: Palau to ban sunscreen products to protect reefs". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Hughes T. "There's insufficient evidence your sunscreen harms coral reefs". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- "New study measures UV-filter chemicals in seawater and corals from Hawaii: First study to look at UV-filter concentrations in coral tissue in US". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- "NICNAS Cosmetics Guidelines". Australian Government Department of Health. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "Guidance Document Sunscreen Monograph". Health Canada. 2012-12-03. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Aguirre C. "Shedding Light on Sun Safety – Part Two". The International Dermal Institute. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "EUR-Lex - 32017R0238 - EN - EUR-Lex".

- "Standards for Cosmetics" (PDF). Ministry of Health and Welfare Notification No.331 of 2000. Japanese Government. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- McGrath M (November 2018). "Palau to ban sunscreen to save coral reefs". BBC News.

- "Suncreen Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use". Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. FDA. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Folley A (2 May 2018). "Hawaii lawmakers approve ban on sunscreens with chemicals harmful to coral reefs". The Hill. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Galamgam J, Linou N, Linos E (November 2018). "Sunscreens, cancer, and protecting our planet". The Lancet. Planetary Health. 2 (11): e465–e466. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30224-9. PMID 30396433.

- Filosa G (February 5, 2019). "Key West bans the sale of sunscreens that hurt coral reefs in the Keys". Miami Herald. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- "SB 172: Florida Drug and Cosmetic Act". The Florida Senate. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "Miami Beach Commissioners Vote Not To Ban Sunscreen Ingredients Experts Say Harm Coral Reefs". 2019-03-13. Retrieved 2019-04-07.