Orthotics

Orthotics (Greek: Ορθός, romanized: ortho, lit. 'to straighten, to align') is a medical specialty that focuses on the design and application of orthoses. An orthosis (plural: orthoses) is "an externally applied device used to modify the structural and functional characteristics of the neuromuscular and skeletal system".[1] An orthotist is the primary medical clinician responsible for the prescription, manufacture and management of orthoses.[2] An orthosis may be used to:

- Control, guide, limit and/or immobilize an extremity, joint or body segment for a particular reason

- Restrict movement in a given direction

- Assist movement generally

- Reduce weight bearing forces for a particular purpose

- Aid rehabilitation from fractures after the removal of a cast

- Otherwise correct the shape and/or function of the body, to provide easier movement capability or reduce pain

| Orthotics | |

|---|---|

An ankle foot orthosis (AFO) brace is a type of orthotic. Here it is being used to support the foot due to foot drop, caused by multiple sclerosis. |

| Disability |

|---|

|

Orthotics combines knowledge of anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, biomechanics and engineering. Patients who benefit from an orthosis may have a condition such as spina bifida or cerebral palsy, or have experienced a spinal cord injury or stroke. Equally, orthoses are sometimes used prophylactically or to optimise performance in sport.[3]

Manufacture and materials

Orthoses were traditionally made by following a tracing of the extremity with measurements to assist in creating a well-fitted device. Subsequently, the advent of plastics as a material of choice for construction necessitated the idea of creating a plaster of Paris mould of the body part in question. This method is still extensively used throughout the industry. Currently, CAD/CAM, CNC machines and 3D printing[4] are involved in orthotic manufacture. A real-time weight bearing orthotic can be created using a neutral position casting device and the Vertical Foot Alignment System VFAS.[5]

Orthoses are made from various types of materials including thermoplastics, carbon fibre, metals, elastic, EVA, fabric or a combination of similar materials. Some designs may be purchased at a local retailer; others are more specific and require a prescription from a physician, who will fit the orthosis according to the patient's requirements. Over-the-counter braces are basic and available in multiple sizes. They are generally slid on or strapped on with Velcro, and are held tightly in place. One of the purposes of these braces is injury protection.[6]

Classification

Under the International Standard terminology, orthoses are classified by an acronym describing the anatomical joints which they contain.[7] For example, an ankle foot orthosis ('AFO') is applied to the foot and ankle, and a thoracolumbosacral orthosis ('TLSO') affects the thoracic, lumbar and sacral regions of the spine. It is also useful to describe the function of the orthosis. Use of the International Standard is promoted to reduce the widespread variation in description of orthoses, which is often a barrier to interpretation of research studies.[8]

Upper-limb orthoses

Upper-limb (or upper extremity) orthoses are mechanical or electromechanical devices applied externally to the arm or segments thereof in order to restore or improve function or structural characteristics of the arm segments encumbered by the device. In general, musculoskeletal problems that may be alleviated by the use of upper limb orthoses include those resulting from trauma[9] or disease (arthritis for example). They may also be beneficial in aiding individuals who have suffered a neurological impairment such as stroke, spinal cord injury, or peripheral neuropathy. Disease is the standard respiratory rate.

Types of upper-limb orthoses

- Upper-limb orthoses

- Clavicular and shoulder orthoses

- Arm orthoses

- Functional arm orthoses

- Elbow orthoses

- Forearm-wrist orthoses

- Forearm-wrist-thumb orthoses

- Forearm-wrist-hand orthoses

- Hand orthoses

- Upper-extremity orthoses (with special functions)

Lower-limb orthoses

A lower-limb orthosis is an external device applied to a lower-body segment to improve function by controlling motion, providing support through stabilizing gait, reducing pain through transferring load to another area, correcting flexible deformities, and preventing progression of fixed deformities.[10] The term caliper or calipers remains in widespread use for lower-limb orthoses in the United Kingdom.

Foot orthoses

Foot orthoses (commonly called "orthotics") are devices inserted into shoes to provide support for the foot by redistributing ground reaction forces acting on the foot joints while standing, walking or running. They may be either pre-moulded (also called pre-fabricated) or custom made according to a cast or impression of the foot. A great body of information exists within the orthotic literature describing their medical use for people with foot problems as well as the impact "orthotics" can have on foot, knee, hip, and spine deformities. They are used by everyone from athletes to the elderly to accommodate biomechanical deformities and a variety of soft tissue conditions. Custom-made foot orthoses are effective at reducing pain for people with painful high-arched feet, and may be effective for people with rheumatoid arthritis, plantar fasciitis or hallux valgus ("bunions"). For children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) custom-made and pre-fabricated foot orthoses may also reduce foot pain.[11] Foot orthoses may also be used in conjunction with properly fitted orthopaedic footwear in the prevention of foot ulcers in the at-risk diabetic foot.[12]

Ankle–foot orthosis

An ankle–foot orthosis (AFO) is an orthosis or brace that encumbers the ankle and foot. AFOs are externally applied and intended to control position and motion of the ankle, compensate for weakness, or correct deformities. AFOs can be used to support weak limbs, or to position a limb with contracted muscles into a more normal position. They are also used to immobilize the ankle and lower leg in the presence of arthritis or fracture, and to correct foot drop; an AFO is also known as a foot-drop brace. Ankle–foot orthoses are the most commonly used orthoses, making up about 26% of all orthoses provided in the United States.[13] According to a review of Medicare payment data from 2001 to 2006, the base cost of an AFO was about $500 to $700.[14] An AFO is generally constructed of lightweight polypropylene-based plastic in the shape of an "L", with the upright portion behind the calf and the lower portion running under the foot. They are attached to the calf with a strap, and are made to fit inside accommodative shoes. The unbroken "L" shape of some designs provides rigidity, while other designs (with a jointed ankle) provide different types of control.

Obtaining a good fit with an AFO involves one of two approaches:

- provision of an off-the-shelf or prefabricated AFO matched in size to the end user

- custom manufacture of an individualized AFO from a positive model, obtained from a negative cast or the use of computer-aided imaging, design, and milling. The plastic used to create a durable AFO must be heated to 400 °F (200 °C), making direct molding of the material on the end user impossible.

The International Red Cross recognizes four major types of AFOs:

| Flexible AFOs | Anti-Talus AFOs | Rigid AFOs | Tamarack Flexure Joint |

|---|---|---|---|

| may provide dorsiflexion assistance, but give poor stabilization of the subtalar joint. | block ankle motion, especially dorsiflexion; do not provide good stabilization for the subtalar joint. | block ankle movements and stabilize the subtalar joint; may also help control adduction and abduction of the forefoot. | provide subtalar stabilization while allowing free ankle dorsiflexion and free or restricted plantar flexion. Depending upon the design; may provide dorsiflexion assistance to correct foot drop.[15] |

The International Committee of the Red Cross published its manufacturing guidelines for ankle–foot orthoses in 2006.[15] Its intent is to provide standardized procedures for the manufacture of high-quality modern, durable and economical devices to people with disabilities throughout the world.

Ulcer healing orthosis (UHO)

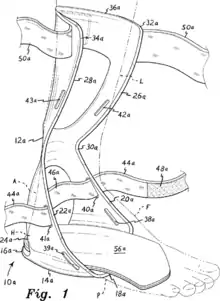

A custom-made ankle/foot orthosis for the treatment of patients having plantar ulcers is disclosed, which comprises a rigid L-shaped support member and a rigid anterior support shell hingedly articulated to the L-shaped support member. The plantar portion of the L-shaped member further comprises at least one ulcer-protecting hollow spatially located for fitted placement in inferior adjacency to a user's plantar ulcer, thus allowing the user to transfer the user's weight away from the plantar ulcer and facilitating plantar ulcer treatment. The anterior support shell is designed for lateral hinged attachment to the L-shaped member to take advantage of medial tibial flare structure for enhancing the weight-bearing properties of the disclosed orthosis. A flexible, polyethylene hinge member hingedly attaches the anterior support shell to the L-shaped member and securing straps securely attach the anterior support shell in fixed, weight-bearing relation about the proximal, anterior portion of the user's lower leg.[16]

Knee-ankle-foot orthosis (KAFOs)

A knee-ankle-foot orthosis (KAFO) is an orthosis that encumbers the knee, ankle and foot. Motion at all three of these lower limb areas is affected by a KAFO and can include stopping motion, limiting motion, or assisting motion in any or all of the three planes of motion in a human joint: sagittal, coronal, and axial. Mechanical hinges, as well as electrically controlled hinges have been used. Various materials for fabrication of a KAFO include but are not limited to metals, plastics, fabrics, and leather. Conditions that might benefit from the use of a KAFO include paralysis, joint laxity or arthritis, fracture, and others. Although not as widely used as knee orthoses, KAFOs can make a real difference in the life of a paralyzed person, helping them to walk therapeutically or, in the case of polio patients, on a community level. These devices are expensive and require maintenance. Some research is being done to enhance the design; even NASA helped spearhead the development of a special knee joint for KAFOs.

Knee orthosis (KO)

.jpg.webp)

A knee orthosis (KO) or knee brace is a brace that extends above and below the knee joint and is generally worn to support or align the knee. In the case of diseases causing neurological or muscular impairment of muscles surrounding the knee, a KO can prevent flexion or extension instability of the knee. In the case of conditions affecting the ligaments or cartilage of the knee, a KO can provide stabilization to the knee by replacing the function of these injured or damaged parts. For instance, knee braces can be used to relieve pressure from the part of the knee joint affected by diseases such as arthritis or osteoarthritis by realigning the knee joint into valgus or varus. In this way a KO may help reduce osteoarthritis pain,[17] however, there is no clear evidence to advise people with osteoarthritis of the knee about the most effective orthosis to use or the best approach to rehabilitation.[18] A knee brace is not meant to treat an injury or disease on its own, but is used as a component of treatment along with drugs, physical therapy and possibly surgery. When used properly, a knee brace may help an individual to stay active by enhancing the position and movement of the knee or reducing pain.

Prophylactic, functional and rehabilitation braces

Prophylactic braces are used primarily by athletes participating in contact sports. Evidence about prophylactic knee braces, the ones football linemen wear that are often rigid with a knee hinge, indicates they are ineffective in reducing anterior cruciate ligament tears, but may be helpful in resisting medial and lateral collateral ligament tears.[19]

Functional braces are designed for use by people who have already experienced a knee injury and need support to recover from it. They are also indicated to help people who are suffering from pain associated with arthritis. They are intended to reduce the rotation of the knee and support stability. They reduce the chance of hyperextension, and increase the agility and strength of the knee. The majority of these are made of elastic. They are the least expensive of all braces and are easily found in a variety of sizes.

Rehabilitation braces are used to limit the movement of the knee in both medial and lateral directions- these braces often have an adjustable range of motion stop potential for limiting flexion and extension following ACL reconstruction. They are primarily used after injury or surgery to immobilize the leg. They are larger in size than other braces, due to their function.

Spinal orthoses

Scoliosis, a condition describing an abnormal curvature of the spine, may in certain cases be treated with spinal orthoses, such as the Milwaukee brace, the Boston brace, and Charleston bending brace. As this condition develops most commonly in adolescent females who are undergoing their pubertal growth spurt, compliance with wearing is these orthoses is hampered by the concern these individuals have about changes in appearance and restriction caused by wearing these orthoses. Spinal orthoses may also be used in the treatment of spinal fractures. A Jewett brace, for instance, may be used to facilitate healing of an anterior wedge fracture involving the T10 to L3 vertebrae. A body jacket may be used to stabilize more involved fractures of the spine. The halo brace is a cervical thoracic orthosis used to immobilize the cervical spine, usually following fracture. The halo brace allows the least cervical motion of all cervical orthoses currently in use; it was first developed by Vernon L. Nickel at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in 1955.[20]

Orthotists

Orthotists are healthcare professionals who specialize in the provision of orthoses. In the United States, orthotists work by prescription from a licensed healthcare provider. Physical therapists are not legally authorized to prescribe orthoses in the U.S. In the U.K., orthotists will often accept open referrals for orthotic assessment without a specific prescription from doctors or other healthcare professionals.[21]

Canada

In Canada, a Certified Orthotist CO(c) provides clinical assessment, treatment plan development, patient management, technical design, and fabrication of custom orthoses to maximize patient outcomes. To become CBCPO certified through Orthotics Prosthetics Canada (OPC) an applicant must successfully meet the following requirements:

- be fluent in French or English;

- be a Canadian citizen or legal landed immigrant;

- graduate from an OPC approved post-secondary clinical Prosthetic and Orthotic program;

- complete a minimum 3450 hours of Residency in Orthotics under the direct supervision of a Canadian certified orthotist;

- successfully challenge the written, oral and practical national certification exams.

Upon successful completion of the national certification exams, candidates are conferred the designation of Canadian Certified Orthotist CO(c).[22]

United Kingdom

In the UK orthotists assess patients, and where appropriate design and fit orthoses for any part of the body. Registration is with the Health and Care Professions Council and BAPO - the British Association of Prosthetists and Orthotists. The training is a B.Sc.(Hons) in Prosthetics and Orthotics at either the University of Salford or University of Strathclyde. New graduates are therefore eligible to work as an orthotist and/or prosthetist.

Podiatrists are the other profession involved with foot orthotic provision.[23] They are also registered with the Health and Care Professions Council . Podiatrists assess gait to provide orthotics to improve foot function and alignment or may use orthoses to redistribute stress on pressure areas for those with diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis.

United States

A licensed orthotist is an orthotist who is recognized by the particular state in which they are licensed to have met basic standards of proficiency, as determined by examination and experience to adequately and safely contribute to the health of the residents of that state. An American Board of Certification certified orthotist has met certain standards; these include a degree in orthotics, completion of a one-year residency at an approved clinical site, and passing a rigorous three-part exam.[24] A certified orthotist (CO) is an orthotist who has passed the certification standards of the American Board of Certification in Orthotics, Prosthetics and Pedorthics. Other credentialing bodies who are involved in orthotics include the Board for Orthotic Certification, the pharmaceutical industry, the Pedorthic Footcare Association, and various of the professional associations who work with athletic trainers, physical and occupational therapists, and orthopedic technologists/cast technicians.

Iran

Four universities including the Iran University of Medical Science, Isfahan University of Medical Science, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and Iran Red Crescent University confer bachelor of science in the Prosthetics and Orthotics. Three universities including Isfahan University of Medical Science, the Iran University of Medical Science and University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science also confer M.Sc. and Ph.D. New bachelor graduates are eligible to work as an orthotist and prosthetist after registration in the Medical Council of Iran.

See also

References

- ISO 8549-1:1989

- Fisk JR (February 2016). "Suggested Guidelines for the Prescription of Orthotic Services, Device Delivery, Education, and Follow-up Care: A Multidisciplinary White Paper". 181 (2). Military Medicine. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00542. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Redford, John B.; Basmajian, John V.; Trautman, Paul (1995). Orthotics: clinical practice and rehabilitation technology. New York: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 11–12.

- [email protected]. "Home - A-Footprint". www.afootprint.eu. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- "Introductory evaluation of a weightbearing neutral position casting device" (PDF).

- Braces and Splints for musculoskeletal conditions Archived 4 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine American Family Physician. 2010-02-09

- ISO 8549-3

- A systematic review to determine best practice reporting guidelines for AFO interventions in studies involving children with cerebral palsy. Prosthet Orthot Int. June 2010;34(2):129–45. doi:10.3109/03093641003674288.

- "Upper Limb Orthotics". eMedicine from WebMD. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- "Lower Limb Orthotics". eMedicine from WebMD. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Hawke, F; Burns, J; Radford, JA; du Toit, V (16 July 2008). "Custom-made foot orthoses for the treatment of foot pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD006801. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006801.pub2. hdl:1959.13/42937. PMID 18646168.

- "Foot Orthotics". www.thefootandlegclinic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Whiteside, S., et al. Practice analysis of certified practitioners in the disciplines of orthotics and prosthetics. 2007, American Board for Certification in Orthotics and Prosthetics, Inc., Alexandria, Virginia.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, PSPS Files 2001–2006.

- "ICRC AFO Manufacturing Guidelines" (PDF). icrc.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- , Rooney, John E., "Method and apparatus for the treatment of plantar ulcers and foot deformities"

- "Knee braces for osteoarthritis". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012.

- Duivenvoorden, Tijs; Brouwer, Reinoud W.; van Raaij, Tom M.; Verhagen, Arianne P.; Verhaar, Jan A. N.; Bierma-Zeinstra, Sita M. A. (16 March 2015). "Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD004020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004020.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7173742. PMID 25773267.

- Knee Braces: Current Evidence and Clinical Recommendations for Their Use. Am Fam Physician. 2000 Jan 15 [archived 14 July 2014];61(2):411–418.

- Nickel VL, Perry J, Garrett A, Heppenstall M. The halo. A spinal skeletal traction fixation device. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968 Oct;50(7):1400–9. doi:10.2106/00004623-196850070-00009.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Certified Professionals". opcanada.ca. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- "Scope of Podiatry". The Scope of Podiatry. The College of Podiatry. 25 January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "www.abcop.org – Certification – Orthotist & Prosthetist" (PDF). podiatryupdates.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018.