Opisthorchiasis

Opisthorchiasis is a parasitic disease caused by species in the genus Opisthorchis (specifically, Opisthorchis viverrini and Opisthorchis felineus). Chronic infection may lead to cholangiocarcinoma, a malignant cancer of the bile ducts.

| Opisthorchiasis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Medical care and loss of wages caused by Opisthorchis viverrini in Laos and in Thailand costs about $120 million annually.[1] Infection by Opisthorchis viverrini and other liver flukes in Asia affect the poor and poorest people.[2] Opisthorchiasis is one of foodborne trematode infections (with clonorchiasis, fascioliasis and paragonimiasis)[3] in the World Health Organization's list of neglected tropical diseases.[2]

Signs and symptoms

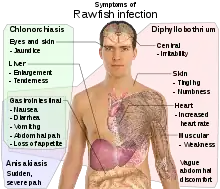

Symptoms of opisthorchiasis (caused by Opisthorchis spp.) are indistinguishable from clonorchiasis (caused by Clonorchis sinensis).[4] About 80% of infected people have no symptoms, though they can have eosinophilia.[1] Asymptomatic infection can occur when there are less than 1000 eggs in one gram in feces.[1] Infection is considered heavy when there are 10,000-30,000 eggs in one gram of feces.[1] Symptoms of heavier infections with Opisthorchis viverrini may include: diarrhoea, epigastric and upper right quadrant pain, lack of appetite (anorexia), fatigue, yellowing of the eyes and skin (jaundice) and mild fever.[1]

These parasites are long-lived and cause heavy chronic infections that may lead to accumulation of fluid in the legs (edema) and in the peritoneal cavity (ascites),[1] enlarged non-functional gall-bladder[1] and also cholangitis, which can lead to periductal fibrosis, cholecystitis and cholelithiasis, obstructive jaundice, hepatomegaly and/or fibrosis of the periportal system.

Chronic opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma

Both experimental and epidemiological evidence strongly implicates Opisthorchis viverrini infections in the etiology of a malignant cancer of the bile ducts (cholangiocarcinoma) in humans which has a very poor prognosis.[5] Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini are both categorized by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as Group 1 carcinogens.[6]

In humans, the onset of cholangiocarcinoma occurs with chronic opisthorchiasis, associated with hepatobiliary damage, inflammation, periductal fibrosis and/or cellular responses to antigens from the infecting fluke.[5] These conditions predispose to cholangiocarcinoma, possibly through an enhanced susceptibility of DNA to damage by carcinogens. Chronic hepatobiliary damage is reported to be multi-factorial and considered to arise from a continued mechanical irritation of the epithelium by the flukes present, particularly via their suckers, metabolites and excreted/secreted antigens as well as immunopathological processes. In silico analyses using techniques of genomics and bioinformatics is unraveling information on molecular mechanisms that may be relevant to the development of cholangiocarcinoma.[7]

In regions where Opisthorchis viverrini is highly endemic, the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is unprecedented.[5] For instance, cholangiocarcinomas represent 15% of primary liver cancer worldwide, but in Thailand's Khon Kaen region, this figure escalates to 90%, the highest recorded incidence of this cancer in the world. Of all cancers worldwide from 2002, 0.02% were cholangiocarcinoma caused by Opisthorchis viverrini.[5] The cancer of the bile ducts caused by opisthorchiasis occur in the ages 25–44 years in Thailand.[8] A few cases have appeared in later life among veterans of the Vietnam war in the United States, who consumed poorly cooked fish from streams in endemic areas near the border of Laos and Vietnam.[9]

Diagnosis

The medical diagnosis is established by finding eggs of Opisthorchis viverrini in feces[1] using the Kato technique.[8] An antigen 89 kDa of Opisthorchis viverrini can be detected by ELISA test.[1]A PCR test capable of amplifying a segment of the internal transcribed spacer region of ribosomal DNA for the opisthorchiid and heterophyid flukes eggs taken directly from faeces was developed and evaluated in a rural community in central Thailand.[10] The lowest quantity of DNA that could be amplified from individual adults of Opisthorchis viverrini was estimated to 0.6 pg.[10]

Prevention

Effective prevention could be readily achieved by persuading people to consume cooked fish (via education programs), but the ancient cultural custom to consume raw, undercooked or freshly pickled fish persists in endemic areas. One community health program, known as the "Lawa" model, has achieved success in the Lawa Lakes region south of Khon Kaen.[11] Currently, there is no effective chemotherapy to combat cholangiocarcinoma, such that intervention strategies need to rely on the prevention or treatment of liver fluke infection/disease.

Cooking or deep-freezing (-20 °C for 7 days)[12] of food made of fish is sure method of prevention.[1] Methods for prevention of Opisthorchis viverrini in aquaculture fish ponds were proposed by Khamboonruang et al. (1997).[13]

Treatment

Chloroquine was used unsuccessfully in attempts to treat opisthorchiasis in 1951–1968.[8] Control of opisthorchiasis relies predominantly on antihelminthic treatment with praziquantel. The single dose of praziquantel of 40 mg/kg is effective against opisthorchiasis (and also against schistosomiasis).[8] Despite the efficacy of this compound, the lack of an acquired immunity to infection predisposes humans to reinfections in endemic regions. In addition, under experimental conditions, the short-term treatment of Opisthorchis viverrini-infected hamsters with praziquantel (400 mg per kg of live weight) induced a dispersion of parasite antigens, resulting in adverse immunopathological changes as a result of oxidative and nitrative stresses following re-infection with Opisthorchis viverrini, a process which has been proposed to initiate and/or promote the development of cholangiocarcinoma in humans.[7] Albendazole can be used as an alternative.[14]

A randomised-controlled trial published in 2011 showed that the broad-spectrum anti-helminthic, tribendimidine, appears to be at least as efficacious as praziquantel.[15] Artemisinin was also found to have anthelmintic activity against Opisthorchis viverrini.[16]

Epidemiology

Opisthorchiasis is prevalent where raw cyprinid fishes are a staple of the diet.[17] Prevalence rises with age; children under the age of 5 years are rarely infected by Opisthorchis viverrini. Males may be affected more than females.[18][19] The WHO estimates that foodborne trematodiases (infection by worms or "flukes", mainly Clonorchis, Opisthorchis, Fasciola and Paragonimus species) affect 56 million people worldwide and 750 million are at risk of infection.[20][21] Eighty million are at risk of opisthorchiasis,[22] 67 million from infection with Opisthorchis viverrini in Southeast Asia and 13 million from Opisthorchis felineus in Kazakhstan, Russia including Siberia, and Ukraine.[23] In the lower Mekong River basin, the disease is highly endemic, and more so in lowlands,[17] with a prevalence up to 60% in some areas of northeast Thailand. However, estimates using newer polymerase chain reaction-based diagnostic techniques indicate that prevalence is probably grossly underestimated.[24] In one study from the 1980s, a prevalence of over 90% was found in persons greater than 10 years old in a small village near Khon Kaen in northeast Thailand in the region known as Isaan.[25] Sporadic cases have been reported in case reports from Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines.[21] Although overall prevalence declined after initial surveys in the 1950s, increases since the 1990s in some areas seem associated with large increases in aquaculture.[23]

Research

Using CRISP gene editing technology, researchers eliminated the genes responsible for symptoms of O viverrini infection in animal models, which may lead to further research toward novel treatment and control of opisthorchiasis and prevention of cholangiocarcinoma.[26]

References

- Muller R. & Wakelin D. (2002). Worms and human disease. CABI. page 43-44.

- Sripa, B. (2008). Loukas, Alex (ed.). "Concerted Action is Needed to Tackle Liver Fluke Infections in Asia". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (5): e232. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000232. PMC 2386259. PMID 18509525..

- "Foodborne trematode infections". WHO. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- King, S.; Scholz, T. Š. (2001). "Trematodes of the family Opisthorchiidae: A minireview". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 39 (3): 209–221. doi:10.3347/kjp.2001.39.3.209. PMC 2721069. PMID 11590910.

- Sripa, B; Kaewkes, S; Sithithaworn, P; Mairiang, E; Laha, T; Smout, M; Pairojkul, C; Bhudhisawasdi, V; Tesana, S; Thinkamrop, B; Bethony, JM; Loukas, A; Brindley, PJ (July 2007). "Liver fluke induces cholangiocarcinoma". PLOS Medicine. 4 (7): e201. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040201. PMC 1913093. PMID 17622191.

- "IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans". monographs.iarc.fr. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Young, ND; Campbell, BE; Hall, RS; Jex, AR; Cantacessi, C; Laha, T; Sohn, WM; Sripa, B; Loukas, A; Brindley, PJ; Gasser, RB (22 June 2010). "Unlocking the transcriptomes of two carcinogenic parasites, Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 4 (6): e719. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000719. PMC 2889816. PMID 20582164.

- World Health Organization (1995). Control of Foodborne Trematode Infection. WHO Technical Report Series. 849. PDF part 1, PDF part 2. page 89-91.

- "Still Fighting: Vietnam Vets Seek Help for Rare Cancer". The New York Times. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Traub, R. J.; MacAranas, J.; Mungthin, M.; Leelayoova, S.; Cribb, T.; Murrell, K. D.; Thompson, R. C. A. (2009). Sripa, Banchob (ed.). "A New PCR-Based Approach Indicates the Range of Clonorchis sinensis Now Extends to Central Thailand". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 3 (1): e367. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000367. PMC 2614470. PMID 19156191..

- Head, Jonathan (13 June 2015). "Deadly dish: the dinner that can give you cancer". BBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- World Health Organization (2004). REPORT JOINT WHO/FAO WORKSHOP ON FOOD-BORNE TREMATODE INFECTIONS IN ASIA. Report series number: RS/2002/GE/40(VTN). 55 pp. PDF. pages 15-17.

- Khamboonruang, C.; Keawvichit, R.; Wongworapat, K.; Suwanrangsi, S.; Hongpromyart, M.; Sukhawat, K.; Tonguthai, K.; Lima Dos Santos, C. A. (1997). "Application of hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) as a possible control measure for Opisthorchis viverrini infection in cultured carp (Puntius gonionotus)". The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 28 Suppl 1: 65–72. PMID 9656352..

- "Opisthorchiasis - Treatment Information". CDC - DPDx. 2013-11-29. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- Soukhathammavong, P.; Odermatt, P.; Sayasone, S.; Vonghachack, Y.; Vounatsou, P.; Hatz, C.; Akkhavong, K.; Keiser, J. (2011). "Efficacy and safety of mefloquine, artesunate, mefloquine–artesunate, tribendimidine, and praziquantel in patients with Opisthorchis viverrini: A randomised, exploratory, open-label, phase 2 trial" (PDF). The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 11 (2): 110–118. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70250-4. PMID 21111681.

- Keiser, J.; Utzinger, J. R. (2007). "Artemisinins and synthetic trioxolanes in the treatment of helminth infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 20 (6): 605–612. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f19ec4. PMID 17975411. S2CID 34591129..

- Sithithaworn, P; Andrews, RH; Nguyen, VD; Wongsaroj, T; Sinuon, M; Odermatt, P; Nawa, Y; Liang, S; Brindley, PJ; Sripa, B (March 2012). "The current status of opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis in the Mekong Basin". Parasitology International. 61 (1): 10–6. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.08.014. PMC 3836690. PMID 21893213.

- Farrar, Jeremy; Hotez, Peter; Junghanss, Thomas; Kang, Gagandeep; Laloo, David; White, Nicholas (2013). Manson's tropical diseases (New ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders [Imprint]. ISBN 978-0702051012.

- Kaewpitoon, N; Kaewpitoon, SJ; Pengsaa, P (21 April 2008). "Opisthorchiasis in Thailand: review and current status". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (15): 2297–302. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.2297. PMC 2705081. PMID 18416453.

- "Foodborne trematodiases". World Health Organization. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Sripa, B; Kaewkes, S; Intapan, PM; Maleewong, W; Brindley, PJ (2010). "Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia epidemiology, pathology, clinical manifestation and control". Advances in Parasitology. 72: 305–50. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(10)72011-X. PMID 20624536.

- Keiser, J; Utzinger, J (July 2009). "Food-borne trematobiases". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (3): 466–83. doi:10.1128/cmr.00012-09. PMC 2708390. PMID 19597009.

- Keiser, J; Utzinger, J (October 2005). "Emerging foodborne trematodiasis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (10): 1507–14. doi:10.3201/eid1110.050614. PMC 3366753. PMID 16318688.

- Johansen, MV; Sithithaworn, P; Bergquist, R; Utzinger, J (2010). "Towards improved diagnosis of zoonotic trematode infections in Southeast Asia". Advances in Parasitology. 73: 171–95. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(10)73007-4. ISBN 9780123815149. PMID 20627143.

- Upatham, ES; Viyanant, V; Kurathong, S; Brockelman, WY; Menaruchi, A; Saowakontha, S; Intarakhao, C; Vajrasthira, S; Warren, KS (November 1982). "Morbidity in relation to intensity of infection in Opisthorchiasis viverrini: study of a community in Khon Kaen, Thailand". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 31 (6): 1156–63. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.1156. PMID 6983303.

- "CRISPR/Cas9 shown to limit impact of certain parasitic diseases". www.bionity.com. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|