Fasciola

Fasciola, commonly known as the liver fluke, is a genus of parasitic trematodes. There are two species within the genus Fasciola: Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica, as well as hybrids between the two species. Both species infect the liver tissue of a wide variety of mammals, including humans, in a condition known as fascioliasis. F. hepatica measures up to 30 mm by 15 mm, while F. gigantica measures up to 75 mm by 15 mm.[2]

| Fasciola | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fasciola hepatica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Rhabditophora |

| Order: | Plagiorchiida |

| Family: | Fasciolidae |

| Genus: | Fasciola Linnaeus, 1758[1] |

Species

- Fasciola hepatica Linnaeus, 1758[1]

- Fasciola gigantica Cobbold, 1855[3]

- Hybrid or introgressed populations of Fasciola gigantica × Fasciola hepatica[4]

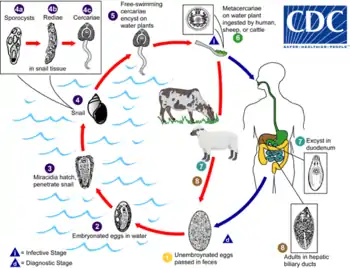

Life cycle

Fasciola pass through five phases in their life cycle: egg, miracidium, cercaria, metacercaria, and adult fluke.[2] The eggs are passed in the feces of mammalian hosts and, if they enter freshwater, the eggs hatch into miracidia. Miracidia are free-swimming. The miracidia then infect gastropod intermediate hosts and develop into cercariae, which erupt from the body of the snail host and find and attach to aquatic plants.[5] The cercariae then develop into metacercarial cysts. When these cysts are ingested along with the aquatic plants by a mammalian host, they mature into adult flukes and migrate to the bile ducts.[5] The adults can live for 5–10 years in a mammalian host.[6]

Animal hosts

The intermediate hosts, where Fasciola reproduce asexually, are gastropods from the family Lymnaeidae, also known as pond snails.[7]

A wide variety of mammals can be definitive hosts, where Fasciola reach adulthood and reproduce, including pigs, rodents, ruminants, and humans.[8] The most important animal reservoir hosts for human infections are sheep and cattle.[9]

Geographic distribution

Fasciola are widespread and inhabit 70 countries and parts of all continents except for Antarctica. It is most common in areas with sheep and cattle are raised.[2] The regions most impacted by Fasciola are the northern Andes and the Mediterranean region.[10][11]

History and discovery

Evidence of fascioliasis in humans exists dating back to Egyptian mummies that have been found with Fasciola eggs.[12] Cercariae of F. hepatica in a snail and flukes infecting sheep were first observed in 1379 by Jehan De Brie.[11][13] The life cycle and hatching of an egg were first described in 1803 by Zeder.[14]

Prevention and treatment

Fascioliasis is treated with triclabendazole. There is no vaccine for Fasciola currently available.[2] In severe cases of biliary tract obstruction, surgery is an option to remove adult flukes.[6]

The most common way that humans are infected is through the consumption of undercooked vegetables, often watercress, that are contaminated with metacercariae.[15] This is of particular concern in areas where animal waste is used as fertilizer for the cultivation of watercress, as the full life cycle of Fasciola can sustained while contaminating crops intended for human consumption.[11] Additionally, in rare cases, ingestion of the raw liver of an infected animal can lead to infection. This is primarily in the Middle East and is known as halzoun.[13]

One prevention method is to kill off the snail hosts in a water body using molluscicides.[16] Another method is treating entire communities that are at risk for contracting fascioliasis with triclabendazole.[10] This is a time efficient method in impoverished rural communities, as it does not require testing the entire community for fascioliasis.[10]

References

- Linnæi, C. (1758–1759). Systema Naturæ per Regna Tria Naturæ, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Haracteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Holmiæ: Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii.

- Prevention, CDC-Centers for Disease Control and (2019-04-16). "CDC - Fasciola - General Information - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- Cobbold, T. S. (1855). Description of a new trematode worm (Fasciola gigantica). The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, Exhibiting a View of the Progressive Discoveries and Improvements in the Sciences and the Arts. New Series, II, 262–267.

- Young N. D., Jex A. R., Cantacessi C., Hall R. S., Campbell B. E. et al. (2011). "A Portrait of the Transcriptome of the Neglected Trematode, Fasciola gigantica—Biological and Biotechnological Implications". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 5(2): e1004. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001004.

- Prevention, CDC-Centers for Disease Control and (2019-05-03). "CDC - Fasciola - Biology". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- Prevention, CDC-Centers for Disease Control and (2019-05-24). "CDC - Fasciola - Resources for Health Professionals". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- Dalton, J. P. (John Pius), 1958- (1999). Fasciolosis. CABI Pub. ISBN 0851992609. OCLC 39728053.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Caron, Yannick; Celi-Erazo, Maritza; Hurtrez-Boussès, Sylvie; Lounnas, Mannon; Pointier, Jean-Pierre; Saegerman, Claude; Losson, Bertrand; Benítez-Ortíz, Washington (2017). "IsGalba schirazensis(Mollusca, Gastropoda) an intermediate host ofFasciola hepatica(Trematoda, Digenea) in Ecuador?". Parasite. 24: 24. doi:10.1051/parasite/2017026. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 5492793. PMID 28664841.

- Pottinger, Paul S.; Jong, Elaine C. (2017), "Trematodes", The Travel and Tropical Medicine Manual, Elsevier, pp. 588–597, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-37506-1.00048-9, ISBN 9780323375061

- "WHO | Fascioliasis diagnosis, treatment and control strategy". WHO. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- "Medical Chemical Corporation: Para-site". www.med-chem.com. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- Mòdol, Xavier (2018-10-26), "The challenge of providing primary health care services in crisis countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region", Family Practice in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, CRC Press, pp. 137–152, doi:10.1201/9781351016032-11, ISBN 9781351016032

- "Fasciola". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- "History". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- "Watercress and Parasitic Infection". www.cfs.gov.hk. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- "Prevention". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-18.