Operation Spring Awakening

Operation Spring Awakening (German: Unternehmen Frühlingserwachen) was the last major German offensive of World War II. The operation was referred to in Germany as the Plattensee Offensive and in the Soviet Union as the Balaton Defensive Operation. It took place in Western Hungary on the Eastern Front and lasted from March 6th until March 15, 1945. It was a failure for Nazi Germany.

| Operation Spring Awakening | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

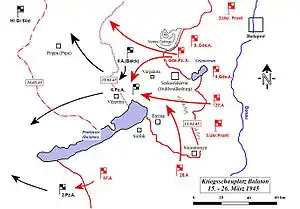

German advances during the operation | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

(Army Group South) (6th Army) (2nd Panzer Army) (6th Panzer Army) (Army Group E) (Army Group F) (Luftflotte 4) Third Army (Hungary) |

(3rd Ukrainian Front) (4th Guards Army) (26th Army) (27th Army) (5th Air Army) (17th Air Army) (57th Army) (1st Bulgarian Army) (3rd Army (Yugoslav Partisans) | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

German offensive (6–15 March 1945):

Soviet counter-offensive (16 March–15 April 1945):

|

German offensive (6–15 March 1945):

Bulgarian casualties:

| ||||||

The operation, initially planned for March 5, began after German units were moved in great secrecy around Lake Balaton (German: Plattensee) to secure the last significant oil reserves still available to the Axis powers and prevent the Red Army from advancing towards Vienna. Many German units were involved, including the 6th Panzer Army and its subordinate Waffen-SS divisions after being withdrawn from the failed Ardennes Offensive on the Western Front. The Germans attacked in three prongs: Frühlingserwachen in the Balaton-Lake Velence-Danube area, Eisbrecher south of Lake Balaton, and Waldteufel south of the Drava-Danube triangle. The advance stalled on March 15, and on March 16 the Red Army and allied units began their delayed Vienna Offensive.

Background

On January 12, Hitler received confirmation that the Soviet Red Army had begun a massive winter offensive through Poland named the Vistula-Oder Offensive.[15] Hitler ordered OB West Field Marshal Gerd Von Rundstedt to withdraw the following units from active combat in the Battle of the Bulge: I SS Panzer Coprs with 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte and 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, along with II SS Panzer Corps with 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich and 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen.[15] These units were to be refitted by January 30 and attached to the 6th Panzer Army under the command of Sepp Dietrich for the upcoming Operation Spring Awakening. Hitler wanted to secure the extremely vital Nagykanizsa oil fields of southern Hungary, as this was the most strategically valuable asset remaining on the Eastern Front.[16] The deadline of January 30 proved impossible for refitting to be completed.

As Operation Spring Awakening would be of great importance, lengthy preparation and strategic care was taken so as to not reveal the offensive. But while the 6th Panzer Army was refitting in Germany, Hitler ordered a preliminary offensive with a similar object to be conducted,[17] resulting in Operation Konrad III beginning January 18. The objectives of Konrad III included relieving besieged Budapest and the recapturing of the Transdanubia region. By January 21, only 5 days into Operation Konrad III, the Germans had taken the towns of Dunapentle and Adony which reside on the Western shore of the Danube.[18] Their push resulted in the annihilation of the Soviet 7th Mechanized Corps. This sudden and savage push caused the Soviet command to actually contemplate an evacuation to the opposite shore.[18] Before the end of the 4th day, the Germans had recaptured 400 square kilometers of territory, an achievement comparable to the initial German gains during the Ardennes Offensive and the Western Front in December 1944.[19] At the height of Operation Konrad III, February 26, the Axis front lines had reached within 20 km of Buda's Southern parameter, and about 10 km within the Northern parameter, but their forces were exhausted.[17]

From January 27 through February 15, the Soviets conducted numerous successful counter-attacks, forcing the Germans to give up the greater portion of their territorial gains, pushing the front line back to the area between Lake Velence, the village of Csősz, and Lake Balaton.[20] This area had the Margit Line running right through it, and would see more fighting in the upcoming Operation Spring Awakening.

By mid-February, the Soviet bridgehead across the Garam River (Hron) north of Esztergom was identified as a threat. This bridgehead would jeopardize the upcoming Spring Awakening's South-Eastern push past Lake Balaton to secure the southern Hungarian oilfields while also exposing a straight route towards Vienna. Thus beginning on February 17, Operation Southwind began the effort to secure the Garam bridgehead from the 2nd Ukrainian Front, and by February 24 the task was successfully achieved, proving to be the very last successful German offensive of the war.

German plan

Creation of Operation Spring Awakening

During a Situation Conference on January 7, 1945 at which both Hermann Göring and OB West Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt were present, Hitler proposed his intention of pulling the 6th SS Panzer Army to form a reserve due to severe Allied air attacks.[22] Von Rundstedt received the withdrawal orders on January 8, and the Panzer Army's divisions began preparations to withdraw from the Front.[23] The slow withdrawal was greatly hampered by Allied air superiority.[24]

On January 12, the Soviet 1st Ukrainian and 1st Belorussian Fronts began their Vistula-Oder Offensive with over 2 million men[25] placing considerable new pressure on the Eastern Front. When this news reached Hitler, he immediately began to plan a major offensive on this Front. Meanwhile, during January 14 on the Western Front, the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer divisions had to be recommitted back from reserves due to successful allied fighting.[23] On January 20, Hitler ordered Gerd Von Rundstedt to withdraw forces from the ongoing Battle of the Bulge; the 1st SS, 2nd SS and 12th SS Divisions managed to disengage and withdraw the same day.[26] Almost all support units of the 6th SS Panzer Army were pulled from the Ardennes by January 22, while the 9th SS Panzer Division was the last to leave on January 23.[26]

On this same day, January 22, Hitler decided that the 6th SS Panzer Army should not be sent back to the Western Front, but rather to Hungary, a view Heinz Guderian (OKH) partially agreed on; Guderian wanted the 6th SS Panzer Army on the Eastern Front, but there to mainly protect Berlin.[24] A glimpse of the ensuing verbal exchange during this argument was captured in Alfred Jodl's (OKW) post-war interrogation where he states Hitler said: "You want to attack without oil- good, we'll see what happens when you attempt that".[27]

However, the main reason for sending the 6th SS Panzer Army south into Hungary can be understood through the list of main strategic points listed in a Situation in the East conference held on January 23: 1) The Hungarian oil region and Vienna oil region which made up 80% of reserves, without which the war effort could not be continued, 2) the Danzig estuary vital for U-boat operations and Upper Silesian industrial region for the war economy and coal production.[24] These two quotes illustrate how seriously Hitler viewed his ruling: “Hitler considered the protection of Vienna and Austria as of vital importance and that he would rather see Berlin fall than lose the Hungarian oil area and Austria”,[28] "He [Hitler] accepted the risk of the Russian threat to the Oder east of Berlin".[24]

On January 27, Heinz Guderian was tasked by Hitler to stop the 3rd Ukrainian Front in the vicinity on the Margit-Line in order to protect the vital oil fields.[29] The following day, January 28, this operation received its preliminary name, Operation Süd (G:South).[29] The main objectives of the operation were as follows: 1) the security of vital raw materials such as oil, bauxite, and manganese for iron, 2) arable land for food and crops, the Austrian military industrial complex, and the city of Vienna, 3) to stop the Soviet Advance.[29] Interestingly, an additional side-objective was the hope that serious pressure on the Southern Soviet Fronts in Hungary would force the Soviet Command to divert some forces from its Northern Offensives headed to Berlin towards Hungary.[29][24]

Operation Süd was scheduled to start after a path to Budapest had been established.[29] The operation was considered to be a success if 1) Operation Konrad III could pin the Soviets between the Vértes mountains and the Danube, 2) the 8th Army could secure its Front in Northern Hungary, 3) if the incoming panzer armies could be refitted during transit to create the advantage of surprise.[29]

Four plans for Operation Süd were produced by high-ranking officials from Army Group South, the 6th SS Panzer Army, and the 6th Army: “Lösung A” by Fritz Krämer of the 6th SS Panzer Army; “Lösung B” and “Lösung C2” by Helmuth Von Grolman of Army Group South; and “Lösung C1” by Heinrich Gaedcke of the 6th Army, with much fighting and bickering as to which plan should be implemented.[30] Army Group South commander Otto Wöhler chose “Lösung B”.[30]

The four plans were sent to Heinz Guderian on February 22 for review, and Army Group South informed Army Group F commander Maximilian von Weichs on February 23 that the operation would commence on March 5, in anticipation that Operation Südwind (G:Southwind) would have finished successfully by February 24.[31] If Operation Southwind was successful, Operation Süd's start could be deferred by 8–9 days.[32] On February 25, Hitler ordered Otto Wöhler, Maximilian von Weichs, and Sepp Dietrich to personally present the plans for Operation Süd to him, along with Guderian (OKH) and Alfred Jodl (OKW),[33] at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, where he ultimately chose “Lösung C2”.[32] Gudarian then ordered Otto Wöhler to increase the daily fuel allowance from 400 to 500 cubic meters (400k to 500k liters) of fuel on February 26,[34] and by the February 28 the specifics of the now officially named “Operation Frühlingserwachen” (G:Spring Awakening) was completed.[32] As per “Lösung C2” 3 offensive prongs were planned, with the main attack of the 6th Army and 6th SS Panzer Army “Frühlingserwachen” being directed towards the Danube through Lakes Velence and Balaton; the 2nd Panzer Army’s “Eisbrecher” (G:Icebreaker) attacking eastward from the western end of Lake Balaton; and the LXXXXI Corps’ “Waldteufel” (G:Forest Devil) attacking north from the Drava River.[35]

Overarching German military structure

The planning of Operation Spring Awakening is as interesting as the offensive itself, due to the chaotic nature of German military command this late in the war. OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) was the overarching military command for the German army in WW2, while the OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres) was officially a high command operating under OKW. Adolf Hitler was the Commander-in-chief of OKH, while also being the supreme commander of OKW.[36] Finding itself issuing more and more direct orders, OKW eventually became responsible for Western and Southern commands, while OKH was responsible for Eastern commands.[36] This operational overlap caused by the centralized command led to disagreements, shortages, waste, inefficiencies, and delays, often escalating to the point where Hitler himself would have to give the final ruling on a matter.[36]

For Operation Spring Awakening, the area for the new offensive was set on the borderline between OKW (Army Group F) and OKH (Army Group South), and this would cause troubles.[36] Army Group E wanted to assemble its troops north of the Drava River by February 25, but Army Group South was not prepared to start the offensive this early due to the ongoing Operation Southwind; subsequently, the OKW and Hitler grew more impatient.[37] The chosen course of action on February 25, "Lösung C2", favored the quicker and farther-reaching joint operation of the 2nd Panzer Army and 6th SS Panzer Army, while "Lösung B" opted to first secure the left flank of the main thrust "Frühlingserwachen" (between Lake Velence and the Danube) before moving south toward the 2nd Panzer army. Guderian was in favor of "Lösung C2" because this plan would shorten the time the 6th SS Panzer Division would need to stay in Hungary. The OKW and OKH did not use common terminology for parts of the offensive, as OKH referred to the entire offensive as Frühlingserwachen, while the OKW referred to the operation attacking north of the Drava as "Waldteufel".[33]

Army Group South and the OKH could not agree on how to best utilize the 1st Cavalry Corps. OKH wanted to send the Corps south-west to the 2nd Panzer army, a move Army Group South Commander Otto Wöhler saw of little use since the 2nd Panzer army would have a lower chance of success compared to the main attacking thrust of “Frühlingserwachen”. Wöhler wanted to use the 1st Cavalry Corps on the eastern shore of Lake Balaton, as German intelligence reported that "the enemy is still the weakest between Lake Balaton and the Sárviz Channel".[38]

To further complicate matters, due to the limited number of newly trained personnel this late in the war, units under Waffen-SS command were often kept at acceptable capacity levels using Wehrmacht personnel. For instance, only 1/3 of the 6th SS Panzer Army's staff were actually from the Waffen-SS.[39]

Arrival into the Hungarian theater

When withdrawing from the Western Front, elements of the III. Flak-Korps were tasked with protecting the 6th SS Panzer Army while en route to Zossen south of Berlin.[26] From here the units' possible de-training locations would seem to be the cities along the Oder River, however this was a calculated misinformation measure to confuse enemy forces who actually attacked these cities.[40] The real plan for the units of 6th SS Panzer Army was to travel south through Vienna to their first Hungarian destination, the city of Győr and its surrounding area.[40] Other units from other armies were also sent to the Hungarian theater, for example the 16th SS Panzer Grenadier Division Reichsführer-SS who was brought up from Italy through the Brenner straight and sent to the 2nd Panzer Army.[41] Some units necessary for the major offensive did not arrive in Hungary until just a few days before its start, the last being the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen arriving in Győr at the beginning of March.[38] Many of the incoming units also received cover names to help further mask the build-up of forces from the enemy.

| Cover Names[42] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Unit | Official Name | Cover Name |

| 6th SS Panzer Army HQ | HQ | Higher Pioneer Leader Hungary |

| 1st SS Panzer Division | Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler | SS replacement unit "Totenkopf" |

| 2nd SS Panzer Division | Das Reich | SS training group North |

| 9th SS Panzer Division | Hohenstaufen | SS training group South |

| 12th SS Panzer Division | Hitlerjugend | SS replacement unit "Wiking" |

| 16th SS Panzer Gren. Division | Reichsführer-SS | 13th SS Division replacement group |

By February 7, on orders of Hitler, strict secrecy rulings were put into place: death penalty for command infractions, license plates were to be covered, insignia on vehicles and uniforms to be covered, no reconnaissance in forward combat areas, unit movements only by night or overcast conditions, no radio traffic, and the units were not to appear on situation maps.[43]

Prior to these measures, on January 30, 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte was ordered to follow many of the same secrecy measures, including the temporary removal of their cuff titles.[44]

Objectives of the German forces

As per the selected "Lösung C2", the Germans planned to attack Soviet General Fyodor Tolbukhin's 3rd Ukrainian Front.[45] On February 27, Army Group South hosted a Chiefs-of-Staff conference to which the Chiefs-of-staff of the 2nd Panzer Army, 6th SS Panzer Army, 6th Army, 8th Army, and Luftflotte 4 attended; here the plans for Operation Spring Awakening were laid out.[38] The offensive would consist of four forces, three were to be attack forces while one was to be a defense force.[38] Below are the units under their respective command as discussed on February 27.

| “Frühlingserwachen” Attack Force[46] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army Group | Commander | Army | Commander | Corps | Commander | Divisions |

| Army Group South | Otto Wöhler | 6th SS Panzer Army | Sepp Dietrich | I SS Panzer Corps | Hermann Priess | 1st, 12th SS Panzer Divisions |

| II SS Panzer Corps | Wilhelm Bittrich | 2nd 9th SS Panzer Divisions, 23rd Panzer Division, 44th Volksgrenadier Division | ||||

| 1st Cavalry Corps | 3rd, 4th Cavalry Divisions | |||||

| 6th Army | Hermann Balck | III Panzer Corps | Hermann Breith | 1st, 3rd Panzer Divisions, 356th Infantry Division, 25th Hungarian Infantry Division | ||

| “Eisbrecher” Attack Force[46] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army Group | Commander | Army | Commander | Corps | Commander | Divisions |

| Army Group South | Otto Wöhler | 2nd Panzer Army | Maximilian de Angelis | LXVIII Corps | Rudolf Konrad | 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division, 71st Infantry Division |

| XXII Mountain Corps | Hubert Lanz | 1st Volksgrenadier Division, 118th Jäger Division (elements) | ||||

| “Waldteufel” Attack Force[46] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army Group | Commander | Army | Commander | Corps | Commander | Divisions |

| Army Group F | Maximilian von Weichs | Army Group E | Alexander Löhr | LXXXXI Corps | Werner von Erdmannsdorff | 297th Infantry Division, 104th Jäger Division, 11th Luftwaffe Field Division, 1st Cossack Division, |

| Defense Force[46] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army Group | Commander | Army | Commander | Corps | Commander | Divisions |

| Army Group South | Otto Wöhler | 6th Army | Hermann Balck | IV SS Panzer Corps | Herbert Gille | 3rd, 5th SS Panzer Divisions, 96th, 711st Infantry Divisions |

| Third Hungarian Army | József Heszlényi | VIII Corps (Hun.) | Dr Gyula Hankovszky | 2nd Hungarian Armoured Division, 1st Hussar Division, 6th Panzer Division, 37th SS Cavalry Division | ||

| 2nd Panzer Army | Maximilian de Angelis | II Corps (Hun.) | Istvan Kudriczy | 20th Hungarian Infantry Division (2-3 Battalions) | ||

On February 28, the start date for Operation Spring Awakening was finally moved back to March 6, though many commanders felt that a greater delay was necessary.[47] During the first days of March, alarming reports about road and terrain conditions due to the spring thaw flooded Army Group South Headquarters. Such thaws had previously badly affected 3 other operations in the area: planned Operation Spätlese in December, Operation Southwind, and the “Waldteufel” attack forcing a change of location for the attack bridgehead from Osijek to Donji Miholjac.[48] Despite the start of the operation being so close, some additional plans were thought up to help the sluggish assembly speeds of incoming units. On March 3, the 6th SS Panzer Army suggested that a naval assault across Lake Balaton itself could be implemented to help the 1st Cavalry Corps on the southeastern edge, but this turned out to be impossible as the spring storms had blown the pack ice against the southern shore.[49] On March 5, the 6th SS Panzer Army took over command of the Hungarian II Corps, along with its 20th Hungarian Division and 9th replacement Division, hereby becoming responsible for the northern shore of Lake Balaton.[50]

The 6th Panzer Army was responsible for the primary thrust of the offensive, “Frühlingserwachen”. It was to advance from an area north of Lake Balaton, through the two lakes (Balaton and Velence), and southeast to capture territory from the Sió Channel to the Danube. After reaching the Danube, one part of the army would turn north creating a northern spearhead and move along the Danube River to retake Budapest, which had been captured on 13 February 1945. Another part of 6th SS Panzer Army would then turn south and create a southern spearhead. The southern spearhead would move along the Sió to link up with units from German Army Group E, which was to thrust north through Mohács. However, the commanding staff of Army Group E was pessimistic about the LXXXXI Corps' ability to reach Mohács due to the unfavoring terrain and sole dependence on infantry.[51] Nonetheless, if successful, it was envisioned that the meeting of Army Group E's “Waldteufel” and the 6th SS Panzer Army's “Frühlingserwachen” would encircle both the Soviet 26th Army and the Soviet 57th Army.[45]

The 6th Army would join the 6th SS Panzer Army in its thrust southeast to the Danube, then turn north to cover the flank of “Frühlingserwachen”. The 2nd Panzer Army's “Eisbrecher” would advance from an area southwest of Lake Balaton and progress towards Kaposvár to enguage the Soviet 57th Army. All this time, the Hungarian Third Army would hold the area west of Budapest along the Vértes Mountains.[45]

Soviet preparation

Interrupted Soviet offensive preparations

On February 17 of 1945, the Soviet High Command (Stavka) instructed the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts to prepare for an offensive towards Vienna which would begin on March 15.[52] However, from February 17 to 18, the 2nd Ukrainian Front noticed the 1st SS Panzer division Leibstandarte and the 12th SS Panzer division Hitlerjugend fighting at the Garam River (S:Hron) during the German Operation Southwind.[23] Knowing that German Panzer divisions were not created for defensive purposes, the Soviet Fronts in Hungary became suspicious of the enemy's intentions. Prisoners taken during Operation Southwind testified that the Germans were in fact preparing to gather a large offensive force.[23] By February 20, the Soviet fronts in Hungary began to understand what the Germans planned to do.[52] The security of the lands West of the River Danube, particularly in the south which held the Hungarian oil fields, was the Germans' main priority at this stage of the war.

Soviet defensive preparations

As the 2nd Ukrainian Front held the territory of Budapest and the lands north of the Hungarian capital, defensive preparations in this sector were not paid much attention due to the lower likelihood of attack, but this was not the same in the south. 3rd Ukrainian Front marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin ordered his armies to prepare for a German offensive on his entire Front, preparation of which would have to be completed no later then March 3.[53] To ensure sufficient supply of war materials and fuel, stockpiles were set up on either side of the Danube, a ferry was put into use, while additional temporary bridges and gas pipelines were also built on the Danube River.[54][45]

Tolbukhin's plan was to initially slow down the German advance to rob their offensive of momentum, then begin grinding down the attacking armies, then initiate the planned Soviet offensive to finish off the remaining German forces.[53] This plan, along with the strategic deployment of the Soviet forces, was quite similar to that of the Battle of Kursk, although it utilized experiences learned in 1943.[55] The 3rd Ukrainian Front worked on digging in, creating extensive trench networks ideal for anti-tank defenses, along with defensive earthworks for the artillery and infantry.[55] The main differences between the Soviet defenses during the Battle of Kursk and the Balaton Defensive Operation (the Russian name for Operation Spring Awakening) was the relative short time frame allowed for defensive preparations (half a month), the smaller number of Soviet forces partaking in the defensive, and a reduced focus on perfecting the defensive lines as after all the 3rd Ukrainian Front would need to start its offensive from these lines.[55] Other minor differences included the lack or limited use of barbed wire installations, anti-tank obstacles, and bunkers,[55] although the 4th Guards Army command did suggest to place the burnt out wrecks of 38 previously destroyed German tanks into advantageous positions; it is unclear how many were actually set up.[23]

Tolbukhin's 3rd Ukrainian Front had 5 Armies plus 1 Air Army, in addition it also had the 1st Bulgarian Army[56] with the 3rd Yugoslav Partisan Army also partaking in the defense. The 3rd Ukrainian Front would be set up in a two echelon defensive layout, with the 4th Guards Army, 26th Army, and 57th Army, and the 1st Bulgarian Army in the first echelon, while the 27th Army would be held back in the second echelon for reserve.[56] The 4th Guards Army's three Guards Rifle Corps and one Guards Fortified District would be spread out over a 39 km front and reach 30 km deep, broken into two belts with one behind the other.[56] The 26th Army, which was expected to take the brunt of the German offensive, arranged its three Rifle Corps along a 44 km front but only 10–15 km deep.[57] The 26th Army's Corps' would be layered in two belts whose defensive preparations had originally begun back on February 11,[57] prior to any sign of German offensive intentions. The 57th Army's one Guards Rifle and one Rifle Corps were spread along a 60 km front and 10–15 km deep; the Army would receive another Rifle Corps during the fighting.[58] The 27th Army's one Guards Rifle and two Rifle Corps would remain in reserve unless the situation in the 26th Army called for its use.[58] Held in reserve, the 3rd Ukrainian Front also had the 18th Tank Corps and 23rd Tanks Corps, along with the 1st Guards Mechanized Corps and the 5th Guards Cavalry Corps.[59] While these Armies were preparing for the imminent offensive, the 17th Air Army was busy flying reconnaissance missions, although they could not report on much due to excellent German camouflage.[60]

Because of the serious tank losses of January–February along the Margit line, Marshal Tolbukhin ordered that no Front/Army level counter-attacks were to take place, and local tactical attacks should be very limited; the only objective was to hold the Front and grind down the German offensive.[55] The two tanks Corps would remain under the 26th and 27th Armies to be utilized only in dire need.[55] The defensive strategy of the 3rd Ukrainian Front was one of anti-tank defense as this was what the Germans were going to use. On average for every kilometer of Front, 700+ anti-tank and 600+ anti-infantry mines were placed, with these numbers rising to 2,700 and 2,900 respectively in the 26th Army's sector.[61] Between the 4th Guards Army and 26th Guards Army, 66 anti-tank zones were created whose depth reached 30–35 km.[61] Each anti-tank position had 8-16 artillery guns and a similar number of anti-tank guns.[61] A prime example of the scale of defensive installments can be seen in the 26th Army's 135th Rifle Corps. Between February 18 and March 3 the 233rd Rifle Division had dug 27 kilometers of trenches, 130 gun and mortar positions, 113 dugouts, 70 command posts and observation points, and laid 4,249 antitank and 5,058 antipersonnel mines, all this on a frontage of 5 kilometers. Although there were no tanks in this defensive zone, there was an average of 17 anti-tank guns per kilometer forming 23 tank killing grounds.[17]

Overarching Soviet military structure

The Soviet Forces, contrary to the Germans, did not have such odd structural complications as the Soviet Armies could make independent decisions while the Stavka could intervene when asked or if necessary;[62] a much more straight forward military structure with clear boundaries. This is an example of a de-centralized command. It was not uncommon for the Soviets to actually search out and exploit the boundaries between the OKW and OKH as they knew these areas would suffer from poorer military command;[62] the advance to Budapest is an example.[36]

Order of battle

Units involved in Offensive (March 6–15, 1945)

These are the main units that were a part of the Army Groups/Front which saw combat in Operation Spring Awakening.[23][63][64][65][66][67] Please note that the units below are subordinate to the commanding structure under which they spent the most time during the offensive. Units during the final months of the war were very prone to location reassignments as the front situation evolved. Reserve units are not included in the list.

Army Group E - subordinate to Army Group F until March 25, 1945

|

|

German offensive

On the 6 March 1945, the German 6th Army, joined by the 6th SS Panzer Army launched a pincer movement north and south of Lake Balaton. Ten armoured (Panzer) and five infantry divisions, including a large number of new heavy Tiger II tanks, struck 3rd Ukrainian Front, hoping to reach the Danube and link up with the German 2nd Panzer Army forces attacking south of Lake Balaton.[68] The attack was spearheaded by the 6th SS Panzer Army and included elite units such as the LSSAH division. Dietrich's army made "good progress" at first, but as they drew near the Danube, the combination of the muddy terrain and strong Soviet resistance had ground the German advance to a halt.[69]

By the 14 March, Operation Spring Awakening was at risk of failure. The 6th SS Panzer Army was well short of its goals. The 2nd Panzer Army did not advance as far on the southern side of Lake Balaton as the 6th SS Panzer Army had on the northern side. Army Group E met fierce resistance from the Bulgarian First Army and Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavian partisan army, and failed to reach its objective of Mohács.

German losses were heavy. Heeresgruppe Süd lost 15,117 casualties in the first eight days of the offensive. The 6th Panzer Army and the 6th Army had only 332 tanks operational of the original approximately 1,000 operational at the start of the offensive.

On the 15 March, strength returns on this day show the Hohenstaufen with 35 Panther tanks, 20 Panzer IVs, 32 Jagdpanzers, 25 Sturmgeschützes and 220 other self-propelled weapons and armoured cars. 42% of these vehicles were damaged, under short or long-term repair. The Das Reich Division had 27 Panthers, 22 Panzer IVs, 28 Jagdpanzers and 26 Sturmgeschützes on hand (the number of those under repair is not available).[17]

Soviet counterattack - Vienna Offensive

On 16 March, the Soviets forces counterattacked in strength. The Germans were driven back to the positions they had held before Operation Spring Awakening began.[70] The overwhelming numerical superiority of the Red Army made any defense impossible, but Hitler believed victory was attainable.[71]

On 22 March, the remnants of the 6th SS Panzer Army withdrew towards Vienna. By 30 March, the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed from Hungary into Austria. By 4 April, the 6th SS Panzer Army was already in the Vienna area desperately setting up defensive lines against the anticipated Soviet Vienna Offensive. Approaching and encircling the Austrian capital were the Soviet 4th and 6th Guards Tank, 9th Guards, and 46th Armies.[70]

The Soviet's Vienna Offensive ended with the fall of the city on 13 April. By 15 April, the remnants of the 6th SS Panzer Army were north of Vienna, facing the Soviet 9th Guards and 46th Armies. By 15 April, the depleted German 6th Army was north of Graz, facing the Soviet 26th and 27th Armies. The remnants of the German 2nd Panzer Army were south of Graz in the Maribor area, facing the Soviet 57th Army and the Bulgarian First Army. Between 25 April and 4 May, the 2nd Panzer Army was attacked near Nagykanizsa during the Nagykanizsa–Körmend Offensive.

Some Hungarian units survived the fall of Budapest and the destruction which followed when the Soviets counterattacked after Operation Spring Awakening. The Hungarian Szent László Infantry Division was still indicated to be attached to the German 2nd Panzer Army as late as 30 April. Between 16 and 25 March, the Hungarian Third Army had been destroyed about 40 kilometres (25 mi) west of Budapest by the Soviet 46th Army which was driving towards Bratislava and the Vienna area.

On 19 March, the Red Army recaptured the last territories lost during the 13‑day Axis offensive. Sepp Dietrich, commander of the Sixth SS Panzer Army tasked with defending the last sources of petroleum controlled by the Germans, joked that “6th Panzer Army is well named—we have just six tanks left.”[72]

The failure of the operation resulted in the "armband order" that was issued to Sepp Dietrich by Adolf Hitler, who claimed that the troops, and more importantly, the Leibstandarte, "did not fight as the situation demanded."[73] As a mark of disgrace, the Waffen-SS units involved in the battle were ordered to remove their cuff titles. Dietrich did not relay the order to his troops.[69]

See also

- Hungary during the Second World War

- Battle of Budapest – 1944/45

- Operation Konrad III - 1945

- Operation Southwind - 1945

- Battle of the Transdanubian Hills – 1945

- Nagykanizsa–Körmend Offensive – 1945

- Vistula-Oder Offensive -1945

- History of Germany during World War II

- Military history of Bulgaria during World War II

- Prague Offensive – 1945

Notes

- Many were abandoned due to a lack of fuel. [10]

References

Citations

- Frieser et al. 2007, p. 930.

- Számvéber & Norbert 2017, pp. 567–569.

- Aleksei et al. 2014.

- Számvéber & Norbert 2017, pp. 22, 574–575.

- Great Patriotic War without Secracy 2010, p. 184.

- Frieser et al. 2007, p. 941.

- Frieser et al. 2007, p. 942.

- Tucker-Jones, Anthony (2016). The Battle for Budapest. ISBN 978-1473877320.

- Frieser et al. 2007, p. 953.

- Frieser et al. 2007, p. 952.

- O. Baronov, Balaton Defense Operation, Moscow, 2001, P.82-106

- G.F. Krivosheyev, 'Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century', London, Greenhill Books, 1997, ISBN 1-85367-280-7, Page 110

- G.F. Krivosheyev, 'Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century', London, Greenhill Books, 1997, p. 156-7

- G.F. Krivosheyev, 'Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century', London, Greenhill Books, 1997, p.156-7

- "Hitler's Last Offensive: Operation Spring Awakening". Warfare History Network. 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- Duffy, Christopher. Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March on Germany, 1945. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1624-0.

- https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/hitlers-last-offensive-operation-spring-awakening/

- Számvéber, Norbert (2013). Kard a Pajzs Mögött - A "Konrád" hadműveletek története,1945 2.bővített kiadás. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-963-89623-7-9.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz (2007). The Eastern Front 1943–1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts. Germany and the Second World War. VIII. München. p. 913. ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2013). Kard a Pajzs Mögött - A „Konrád” hadműveletek története, 1945 2.bővített kiadás. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 456. ISBN 978-963-89623-7-9.

- Juhász, Attila. "New achievements in WW II. military historical reconstruction with GIS". ResearchGate.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 112. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Aleksei Maksim; Isaev Kolomiets (2014). Tomb of the Panzerwaffe The Defeat of the 6th SS Panzer Army in Hungary 1945. Moscow: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-16-1.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 113. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- "Vistula–Oder Offensive". Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 115. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 120. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Warlimont, Walter (1990). Inside Hitler's Headquarters. p. 499.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 152. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 4. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 148. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 155. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 9. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 116. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 124. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 125. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. p. 419. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 425. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Higgins, David R. (2014). Jagdpanther vs SU-100. Eastern Front 1945. Osprey Publishing.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. pp. 156–157. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 161. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 164. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 169. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 172. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-921991-78-9., Maier (2004). Georg. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 166. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz (2017). Germany and the Second World War - The Eastern Front 1943-1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts. Volume VIII. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 930. ISBN 9780198723462.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. PeKo Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna. Canada: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Horváth, Gábor (2013). Bostonok a Magyar Égen és Földben (1944-1945). Szolnok: Self-Published.

- "Lexicon der Wehrmacht".

- "TsAMO - pamyat-naroda (memory of the people)".

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Webb, William (2017). The Last Attack: Sixth SS Panzer Army and the defense of Hungary and Austria in 1945.

- Glantz & House 1995, p. 253.

- Stein 1984, p. 238.

- Dollinger 1967, p. 182.

- Ziemke 1968, p. 450.

- https://ww2days.com/germans-trapped-in-hungarian-capital-2.html

- Dollinger 1967, p. 198.

Bibliography

- Aleksei Maksim; Isaev Kolomiets (2014). Tomb of the Panzerwaffe The Defeat of the 6th SS Panzer Army in Hungary 1945. Moscow: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-16-1.

- Dollinger, Hans (1967) [1965]. The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. New York: Bonanza. ISBN 978-0-517-01313-7.

- Duffy, Christopher (2002). Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March on Germany, 1945. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1624-0.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz; Schmider, Klaus; Schönherr, Klaus; Schreiber, Gerhard; Ungváry, Kristián; Wegner, Bernd (2007). Die Ostfront 1943/44 – Der Krieg im Osten und an den Nebenfronten [The Eastern Front 1943–1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts]. Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg [Germany and the Second World War] (in German). VIII. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2.

- Fritz, Stephen (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81313-416-1.

- Glantz, David M.; House, Jonathan (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, Kansas: Kansas University Press. ISBN 0-7006-0717-X.

- Horváth, Gábor (2013). Bostonok a Magyar Égen és Földben 1944–1945. Szolnok: Self-Published.

- Maier, Georg (2004). Drama Between Budapest and Vienna: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-921991-78-9.

- Seaton, Albert (1971). The Russo-German War, 1941–45. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-21376-478-4.

- Stein, George H. (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2013). Kárd a Pajzs Mögött - A "Konrád" hadműveletek tőrténete, 1945 2.bővitett kiadás. Budapest. PeKo Publishing. ISBN 978-963-89623-7-9.

- Számvéber, Norbert (2017). Páncélosok a Dunantulon - Az Utolsó Páncélosütközetek Magyarországon 1945 Tavaszán. Budapest: PeKo Publishing. ISBN 978-963-454-083-0.

- Webb, William (2017). The Last Attack: Sixth SS Panzer Army and the defense of Hungary and Austria in 1945.

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1968). Stalingrad to Berlin: The German Defeat in the East. Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History – U.S. Army. ASIN B002E5VBSE.