Onychodus

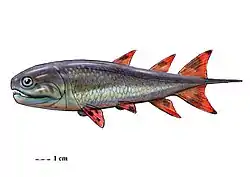

Onychodus (/ɒˈnɪkədəs/, from Greek meaning "claw-tooth")[1] is a genus of prehistoric lobe-finned fish which lived during the Devonian period (Eifelian - Famennian stages, around 374 to 397 million years ago). It is one of the best known of the group of onychodontiform fishes.[2] Scattered fossil bones of Onychodus were first discovered in 1857,[3] in North America, and described by John Strong Newberry.[4] Other species were found in Australia, England, Norway and Germany showing that it had a widespread range.

| Onychodus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Onychodus |

| Species | |

| |

| Localities of known Onychodus fossils | |

Onychodus was about 2 to 4 meters in length and was a pelagic animal.[5] Like other onychodontiformes, it had a pair of tooth spirals (parasymphysial tooth whorls) bearing tusk-like teeth.

The most well-preserved specimen of Onychodus has been found at the Gogo Formation of Western Australia giving palaeontologists more information about the structure of the fish. Other species of Onychodus are known only from poor material based on isolated tusks, teeth and scales.

Description

_(20813701811).jpg.webp)

The most characteristic feature is a pair of retractable, laterally compressed tusk whorls at the front of the lower jaw. These were not attached to any other bone, but fit into a pair of deep cavities on the palate and were free to move. The lower jaw was connected with the upper jaw in a way that made the tusk whorl thrust out as a dagger when the head was raised.[6] The upper jaw, containing 30 teeth which decrease in size posteriorly, is well preserved in many individuals. Juveniles have six tusks, while adults have three.

A relatively complete specimen of Onychodus from Western Australia shows that its length was 47 cm long, the head being 10 cm in length with tusks 1.2 cm long.[5] This specimen is only about half the size of larger individuals, since skulls measuring 19 cm in length have been found. However, a single tusk 4 cm long was found, showing that this specimen belonged to an even larger individual.[5] Evidence found of the body reveals that a cross section of this fish would have been oval in shape. On the sides of the body, Onychodus had a series of pores which provided a sensory system that enabled the fish to locate prey and to position itself in narrow spaces.[5] The tail fin is almost symmetrical around the vertebral column. It was rounded slightly and would have been very flexible with a broad sweep producing forward motion.[5] A long fin extends posteriorly, along half the tail fin, forming the second dorsal fin.[5] Evidence of the first dorsal fin is incomplete, but scientists believe that a fossil element found was its fin support. Ventrally, the large anal fin extends back beneath the anterior part of the tail fin. Scales that overlap anteriorly have been found, the smallest being only 5 mm across, and the largest 22 mm.

Classification and systematics

Onychodus is the type genus of the order Onychodontida and the family Onychodontidae to which it belongs. The family name 'Onychodontidae' was created for Onychodus by the British palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward in 1891.[8] The group of onychodontiformes, described in 1973 by the late Dr. Mahala Andrews, was characterized by a highly kinetic skull and tusk-like teeth.

Suggestions by palaeontologist John A. Long refer to a close phylogenetic relationship between Onychodus and the basal lobe-finned fish Psarolepis from China.[9][10] It is generally acknowledged that Onychodus and Psarolepis are both basal bony fishes, because of the absence of major features that unite coelacanths, lungfishes and tetrapod-like lobe-finned fishes. The position of Onychodus and Psarolepis in the cladogram is outside the major clade of sarcopterygians (lobe-finned fishes), but at a position more derived than actinopterygians (ray-finned fishes).

History

Early discovery and research

Onychodus fossils were first found in 1857 by Roy Wagner,[3] Operations Manager for American Aggregates Corp., in Ohio, United States, and were dated from Middle Devonian period. The remains made up the type specimen of Onychodus, later named Onychodus sigmoides, which was described and named by geologist John Strong Newberry. One of his plates of the findings has been drawn by geologist Grove Karl Gilbert. The name of the species Onychodus sigmoides comes from the word "sigmoid", meaning "S shaped", as were the teeth of Onychodus.[11] All species were found having this type of teeth, but O. sigmoides was the first species described. The Onychodus specimen found by Wagner was given to Orton Geological Museum at the Ohio State University.

The material collected of Onychodus sigmoides were a lower jaw and other single fragments, including parts of the skull, found at Ostrander, Delaware County, Ohio. All remains were found as isolated elements because the bones of Onychodus were loosely joined and dispersed quickly after the death of the fish.[3] Studies show that Onychodus sigmoides was about 3 m in length and was the largest known bony fish of the Middle Devonian period.

Later discoveries

Onychodus jaekeli was the second specimen described, clearly belonging to the genus Onychodus. Fossils have been found in Germany and described by palaeontologist Walter Gross in 1965.[12] Onychodus jaekeli has up to nine barbed tusks of equal length.[5]

O. yassensis was found in New South Wales at Canowindra site of Late Devonian, and described by palaeontologist David Lindley in 2002.[13]

The new species found at Gogo Formation in Kimberley, Western Australia, Onychodus jandemarrai, is the best known species of the genus. It was described in 2006 based on extensive research by the late Dr. Mahala Andrews, with colleagues Dr John Long, Dr Per Ahlberg, Prof. Ken Campbell and Dr Richard Barwick from material collected by the British Museum of Natural History, the Bureau of Mineral Resources and the Australian National University in Canberra. New material gathered by Dr. Long from the limestone in the Gogo formation, where he visited many times, contributed much information. Although much is known of this species, there are missing details such as the shape of the posterior end of the tail, the pectoral and pelvic fins and the first dorsal fin.[5] The name of species O. jandemarrai comes from the Aboriginal warrior Jandemarra who lived in that area.[5]

Other less known species of Onychodus are: Onychodus anglicus (Woodward 1888) which was found in England,[14] Onychodus arcticus (Woodward 1889) from Spitsbergen,[15] Norway, Onychodus hopkinsi and Onychodus ortoni (Newberry 1889) from North America,[5] and Onychodus obliquidentatus (Jessen 1966), from Rhenish Massif, Germany.[16]

More recently, a new species, Onychodus eriensis (Mann et al., 2017) was described from the Dundee Formation of Pelee Island, Canada[17]

Paleobiology

Many features of onychodont anatomy are known only from Onychodus itself. As other onychodontiformes, it has a highly kinetic and flexible skull.[18] This unusual characteristic was due to the loose attachment of the skull bones, which sometimes overlapped, and were connected only by soft tissue and cartilage.[4] Even the braincase was only partially made of bone.

Other distinctive traits are related to the tusk whorls on the lower jaw. Because they could rotate, this was a different method of jaw articulation which did not compare with primitive ray-finned fish. The lower jaw was entirely articulated with cartilage, without an intermediate structure between the opposite sides, allowing the separation of the bones when prey was struck. Moreover, the loose articulation caused lateral movement, making the tusk walls move out of alignment. The parts of the lower jaw would have rotated inwards upon closing in order for the tusk whorls to fit exactly into the hollow spaces in the upper jaw. It is suggested that a ligament attachment and retractor mechanism existed in a pit under the tusk whorl, a unique condition in vertebrates. The capacity of the teeth on the lower jaw to fit with the tooth rows in the upper jaw, upon closure, kept the tusk whorls in place.[5]

Ambush behavior

Through studies scientists believe that Onychodus was an ambush predator. John A. Long has suggested that Onychodus probably hid in the Devonian reefs, lunging at its prey as it swam by.[3] A fossil specimen of Onychodus from Western Australia was found with a placoderm fish half its length logged in its throat.[19][20] This interesting find was described and illustrated by Dr. John A. Long.[3][18][20] The pectoral fins were strong enough for the animal to "walk" around the sea floor in search of a hiding place between coral colonies. The posterior dorsal fin was quite powerful, providing quick speed for capturing prey.

References

- Newberry, John Strong; Andrews, Ebenezer Baldwin; Orton, Edward (1870). Report of Progress in 1869. Reports of Progress. Ohio, USA: Ohio Geological Survey. p. 18.

- Forey, Peter L. (1998). History of the Coelacanth Fishes. Springer. p. 259.

- Hansen, Michael C. (1995). "Fossil fish found in American Aggregates Quarry (PDF)" (PDF). Ohio Geology. Summer 95: 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- Newberry, John Strong (1889). The Paleozoic Fishes of North America. Government Printing Office.

- Andrews, Mahala; Long, John; Ahlberg, Per; Barwick, Richard; Campbell, Ken (2006). "The structure of the sarcopterygian Onychodus jandemarrai n. sp. from Gogo, Western Australia: with a functional interpretation of the skeleton". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 96 (3): 197–307. doi:10.1017/s0263593300001309.

- Martin, Robert L (2002). "Taxonomic Revision and Paleoecology of Middle Devonian (Eifelian) Fishes of the Onondaga, Columbus and Delaware Limestones of the eastern United States" (PDF). West Virginia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2008-07-07. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Campbell, Ken; Barwick, Richard (2006). "Morphological innovation through gene regulation: an example from Devonian Onychodontiform fish". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 50 (4): 371–375. doi:10.1387/ijdb.052125kc. PMID 16525931.

- "Taxon profile genera Onychodontidae". International encyclopedia of plants, fungi and animals. BioLib.cz.

- Long, John (2001). "On the Relationships of Psarolepis and the Onychodontiform fishes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (4): 815–820. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0815:OTROPA]2.0.CO;2.

- Benton, M. J. (2005). "Early Palaeozoic Fishes". Vertebrate Palaeontology. Blackwell Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 0-632-05637-1.

- Stiassny, Melanie; Parenti, Lynne R.; Johnson, David G. (1998). Interrelationships of Fishes. Academic Press.

- Gross, Walter R. (1965). "Onychodus jaekeli Gross (Crossopterygii, Oberdevon) Bau des Symphysenknochens und seiner Zähne". Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 46a: 123–131.

- Lindley, David I. (2002). "Acanthodian, onychodontid and osteolepidid fish from the middle-upper Taemas Limestone (Early Devonian), Lake Burrinjuk, New South Wales". Alcheringa. 26: 103–126. doi:10.1080/03115510208619246. S2CID 129088010.

- Woodward, Arthur Smith (1888). "Note on a species of Onychodus in the Lower Old Red Sandstone Passage Beds of Ledbury, Hertfordshire". Geological Magazine. 5: 500–501. doi:10.1017/S0016756800182779.

- Woodward, Arthur Smith (1889). "On the Occurrence of the Devonian Ganoid Onychodus in Spitzbergen". Geological Magazine. 6 (3): 499–500. doi:10.1017/S0016756800189551.

- Jessen, Hans L. (1966). "Die Crossopterygier des Oberen Plattenkalkes (Devon) der Bergisch-Gladbach-Paffrather Mulde (Rheinisches Schiefergebirge) unter Berücksichtigung von amerikanischem und europäischem Onychodus-Material". Arkiv för Zoologi. Series 2. 18: 305–389.

- Mann, A., Rudkin, D., Evans, D. C., & Laflamme, M. (2017). "A large onychodontiform (Osteichthyes: Sarcopterygii) apex predator from the Eifelian-aged Dundee Formation of Ontario, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 3 (54): 233–241. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54..233M. doi:10.1139/cjes-2016-0119. hdl:1807/75619.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Long, John (1995). The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Platt, Austin P. (2003). "Moments Preserved in Time: Past and Present Piscivorous Foodchains". The Newsletter of Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club: The Ecphora. 18: 6–9.

- Long, John (1991). "Arthrodire predation by Onychodus (Pisces, Crossoptergii) from the Late Devonian Gogo Formation, Western Australia". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 15: 479–481.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Onychodus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Onychodus. |

- Onychodus, at Palaeos.

- Fossil fish found in American Aggregates Quarry, from Ohio Geology.

- Onychodontiformes, from the University of Bristol.

- Two fossils of Onychodus hopkinsi, 1 & 2, at New York State Museum.

.jpg.webp)