Nuclear power in Italy

Nuclear power in Italy is a controversial topic. Italy started to produce nuclear energy in the early 1960s, but all plants were closed by 1990 following the Italian nuclear power referendum. As of 2018, Italy is one of only two countries, along with Lithuania, that completely phased out nuclear power for electricity generation after having operational reactors.

An attempt to change the decision was made in 2008 by the government (see also nuclear power debate), which called the nuclear power phase-out a "terrible mistake, the cost of which totalled over €50 billion".[1] Minister of Economic Development Claudio Scajola proposed to build as many as 10 new reactors, with the goal of increasing the nuclear share of Italy's electricity supply to about 25% by 2030.[2]

However, following the 2011 Japanese nuclear accidents, the Italian government put a one-year moratorium on plans to revive nuclear power.[3] On 11—12 June 2011, Italian voters passed a referendum to cancel plans for new reactors. Over 94% of the electorate voted in favor of the construction ban, with 55% of the eligible voters participating, making the vote binding.[4]

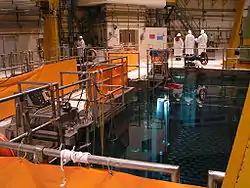

Plants

There are no nuclear power plants in operation in Italy.

| Name | Place | Power (MWe)[5] | Type[5] | Start of operation[5] | Shutdown[5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caorso | Caorso | 860 | BWR | 1978 | 1990 |

| Enrico Fermi | Trino | 260 | PWR | 1964 | 1990 |

| Garigliano | Sessa Aurunca | 150 | BWR | 1964 | 1982 |

| Latina | Latina | 153 | GCR (Magnox) | 1963 | 1987 |

History

Early years

The history of nuclear power in Italy starts at the end of 1946, when the Cise, a small centre for nuclear energy research, was created. A few years later, a public research institute linked to the CNR, the Cnrn (Comitato Nazionale per le Ricerche Nucleari, National Committee for Nuclear Research), was founded. The Cnrn became an autonomous research entity in 1960, the Cnen (Comitato Nazionale per l'Energia Nucleare, National Committee for Nuclear Energy).[6]

During all the 1950s there was a common belief that nuclear energy would have provided within few years, safely and economically, all the energy needed. Italy ordered between 1956 and 1958 3 different reactors from 3 different companies: Westinghouse, General Electric and Npcc. The reactors were built in Trino Vercellese, Sessa Aurunca and Latina and were all completed by 1964.[7]

At that time electric companies in Italy were private and the power plants were built by different private companies. However the electricity sector was nationalized in 1962 with the creation of a new corporation responsible for production and distribution of electricity in the country: Enel. This factor is thought to be the reason for Italy's halt in nuclear investments. In fact, only one reactor was ordered in the following decade: construction of the Caorso power plant started in 1970 and was completed in 1978.[8] At the same time, Italy initiated a nuclear weapons program to produce its own nuclear weapons essentially under the Italian Navy control. CAMEN (then CISAM) close Pisa was used for this aim.[9] It was stopped in the '70s to join NATO nuclear sharing. For this sector Italy has produced the IRBM Alfa and other air vectors. The former Italian President Francesco Cossiga declared officially in Italy secrets about nuclear weapons subject like all military ones are generally hidden by silence or lies. [10]

After the 1973 oil crisis

Italy suffered much from the 1973 oil crisis due to its dependency on imported oil. An attempt to change this potentially dangerous situation was made in the following years. The first PEN (Piano Energetico Nazionale, National energy plan) was approved in 1975. The plan's objective was to lower the country's dependency on fossil fuels by making huge investments in the nuclear energy sector.[11] The document planned an installed nuclear energy capacity of more than 46 GW by 1990.[12] Subsequent plans downsized the commitment. However, by 1986, only one plant was under construction, in Montalto di Castro.

1987 Referendum

Following the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, a debate on nuclear energy started in Italy and eventually led to the nuclear power referendum of November 1987, which polled voters on three issues:

- abolishing the statutes by which the Inter-ministries Committee for the Economical Programming (CIPE) could decide about the locations for nuclear plants, when the Regions did not so within the time stipulated by Law 393;

- abolishing rewards for municipalities in whose territories nuclear or coal plants were to be built;

- abolishing the statutes allowing Enel to take part in international agreements to build and manage nuclear plants.

Some commenters find that the questions were actually too technical for non-experts and were used to obtain popular consent after Chernobyl disaster.[13][14] This was caused by the fact that referendum in Italy can be only abrogative, therefore it can only cancel an act, it can not set a national energy program.

In each referendum Sì ("Yes") won. Subsequently, the Italian government decided in 1988 to phase out existing plants. This led to the termination of work on the near-complete Montalto di Castro Nuclear Power Station, and the early closure of Enrico Fermi and Caorso Nuclear Power Plant, both of which closed in 1990. Italy's other nuclear power plants had already closed prior to the decision. The Montalto di Castro plant was subsequently converted to the Alessandro Volta fossil fuel power station.

In later years, Italy became a larger importer of power, importing approximately 10% of its electricity from France by 2007.

Restoration attempt

On 13 November 2007, during his speech at the World Energy Council in Rome, Italy's nuclear stance was criticized by CEO of Eni, Paolo Scaroni.[15] In January 2008, a think tank Energy Lab started a feasibility study for construction of three or four new nuclear power plants in Italy as a part of a new debate on nuclear power in the country.[16] The Italian general election of April 2008 saw the victory of the People of Freedom, a party which strongly supports nuclear power.[17] Following the election victory, the new Italy's Minister for Economic Development Claudio Scajola announced the scheduling for the start of the construction of a new nuclear-powered plant by 2013.[18]

Enel S.p.A. planned to build new reactors at one of three licensed sites: Garigliano, Latina, or Montalto di Castro. The first two had small reactors operating until 1982 and 1987. At Montalto di Castro two larger reactors were nearly completed when the country's referendum halted the construction in November 1987.[19]

On 24 February 2009, a new agreement between France and Italy was signed, thus allowing Italy to share in France's expertise in the area of nuclear power station design. Under the agreement, a study was to be conducted to determine the feasibility of building 4 new nuclear power stations in Italy.[20] On 9 July 2009 the Italian legislature passed an energy bill covering the establishment of a Nuclear Regulatory Agency and giving the government six months to select sites for new plants.[21]

However, the nuclear agenda of Silvio Berlusconi's government was slowed down due to the strong opposition of ten Italian regions (Basilicata, Calabria, Emilia-Romagna, Lazio, Liguria, Marche, Molise, Apulia, Tuscany and Umbria), that challenged the energy bill passed on 9 July 2009 (the part that gives the government the responsibility for the reopening of nuclear facilities in the country) because they deemed it as unconstitutional. On 24 June 2010 the Italian Constitutional Court rejected the appeal, but the Italian Government had to approve a new version of the Legislative Decree 31/2010 on nuclear sites, in order to adapt it to the decision of the Constitutional Court. The members of the Nuclear Regulatory Agency were named by the government only on 5 November 2010 and the list sent to the Italian Parliament for approval.[22] On 1 December 2010 a joint meeting of the Italian Parliament commissions for the Environment and for Productive Activities rejected one of the nominations putting a further stop to the Italian Government plans.

On 3 August 2009, Enel and Électricité de France established a joint venture, Sviluppo Nucleare Italia Srl, for studying the feasibility of building at least four reactors using Areva's European Pressurized Reactors.[23]

2011 Referendum

The Italian Government put a one-year moratorium on its plans to revive nuclear power, following the 2011 Japanese nuclear accidents.[24] A further Italian nuclear power referendum was held on 13 June 2011, with a 54.79% turnout and 94% of the votes rejecting the use of Nuclear Power,[25] leading to cancellations of any future nuclear power plants planned during the previous years.

Decommissioning

Nuclear power plants in Italy are currently being decommissioned by SOGIN, a company under control of the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance.[26] The company is responsible for the handling of nuclear waste and the dismantling and decontamination of decommissioned power plants. SOGIN also manages nuclear waste from other applications, such as medical devices and scientific centers.[27]

There are plans for the construction of a unique surface storage site for all the Italian nuclear waste, of which about 70% comes from old nuclear power plants.[28] These highly radioactive materials are currently being reprocessed to reduce the total volume.[27]

Nuclear fusion

In the nuclear sector, Italy participates in the development of the ITER fusion reactor to produce clean energy through ENEA.[29]

See also

Notes

- "Nuclear phase out a '€50 billion mistake'". World Nuclear News. 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Italy to build 8–10 nuclear reactors". Calgary Herald. October 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- "Italy puts 1 year moratorium on nuclear". Businessweek. March 23, 2011.

- "Italy Nuclear Referendum Results". June 13, 2011. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012.

- "Italy (Italian Republic): Nuclear Power Reactors". IAEA. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- De Paoli, p. 23

- De Paoli, p. 24

- De Paoli, p. 26

- http://legislature.camera.it/_dati/leg05/lavori/stenografici/sed0073/sed0073.pdf

- "Cossiga: "In Italia ci sono bombe atomiche Usa"" (in Italian). Tiscali. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- De Paoli, p. 29

- De Paoli, p. 30

- Fornaciari, P. (1997). Il petrolio, l'atomo e il metano (in Italian). Edizioni 21mo secolo.

- Nebbia, Giancarlo (2007). Nucleare: il frutto proibito (in Italian). Milan: Bompiani. ISBN 978-88-452-5954-8.

- Uchenna Izundu (2007-11-13). "WEC: Eni chief criticizes Italy's nuclear stance". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. (subscription required). Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- Reuters. Italy renews nuclear power debate. January 9, 2008.

- Forbes. A2A Head wants Italy to build 3 or 4 nuclear power stations. April 14, 2008.

- Giselda Vagnoni (2008-05-02). "Italy should build more nuclear plants - minister". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- "Nuclear Power in Italy". World Nuclear Association (WNA). June 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- "Italy and France pen nuclear deal". BBC News. 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- "Italy rejoins the nuclear family". World Nuclear News. 2009-07-10. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- "Italian nuclear safety agency board named". World Nuclear News. 2010-11-08. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- Selina Williams, Liam Moloney (2009-08-03). "Enel, EDF to Build Nuclear Plants in Italy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- "Italy puts 1 year moratorium on nuclear". Businessweek. March 23, 2011.

- "Italian Home Office". June 6, 2011.

- "Chi siamo" [Who we are]. Sogin. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- "Bonifica ambientale degli impianti nucleari". Sogin. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- "Parco tecnologico e deposito nazionale". Sogin. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- http://www.fusione.enea.it/

References

- De Paoli, Luigi (2011). L'energia nucleare. Bologna: Il Mulino. ISBN 978-88-15-13701-2.

External links

- Nuclear power in Italy at the WNA site.

- Nuclear power profile of Italy at the NEA site.