Mount Athos

Mount Athos (/ˈæθɒs/; Greek: Άθως, [ˈa.θos]) is a mountain and peninsula in northeastern Greece and an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism. It is governed as an autonomous polity within the Hellenic Republic. Mount Athos is home to 20 monasteries under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

Athos / Holy Mountain

| |

|---|---|

Location and extent of Mount Athos (red) in Greece | |

| Capital | Karyesa |

| Languages | |

| Religion | Eastern Orthodoxy |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Country | |

| Government | Autonomous theocratic society led by ecclesiastical council |

| Athanasios Martinos | |

• Protos (Elder Monk) | Elder Symeon Dionysiates |

| Autonomy within Greece | |

• Established under the Constitution of Greece | 1927[1] |

• Reaffirmed | 1975 |

| Area | |

• Total | 335.63 km2 (129.59 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2011 census | 1,811 |

• Density | 5.40/km2 (14.0/sq mi) |

| Currency | Euro[note 1] (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | EET |

Sovereign monasteries

| |

| Mount Athos | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,033[3] m (6,670 ft) |

| Prominence | 2,012 m (6,601 ft) |

| Listing | Ultra |

| Coordinates | 40°09′26″N 24°19′35″E |

| Geography | |

| Location | Greece |

| Type | Mixed |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv, v, vi, vii |

| Designated | 1988 (12th session) |

| Reference no. | 454 |

| State Party | Greece |

| Region | Europe |

Mount Athos is commonly referred to in Greek as the Agion Oros (Άγιον Όρος, 'Holy Mountain'), and the entity as the "Athonite State" (Αθωνική Πολιτεία, Athonikí Politía). Other languages of Orthodox tradition also use names translating to 'Holy Mountain'. This includes Bulgarian, Macedonian and Serbian (Света гора, Света Гора, Sveta Gora); Russian (Святая Гора, Svyataya Gora); and Georgian (მთაწმინდა, mtats’minda). However, not all languages spoken in the region use this name; in Romanian, it is simply called Muntele Athos or Muntele Atos. In the classical era, while the mountain was called Athos, the peninsula was known as Acté or Akté (Koinē Greek: Ἀκτή).

Mount Athos has been inhabited since ancient times and is known for its long Christian presence and historical monastic traditions, which date back to at least AD 800 and the Byzantine era. Today, over 2,000 monks from Greece and many other countries, including Eastern Orthodox countries such as Romania, Moldova, Georgia, Bulgaria, Serbia and Russia, live an ascetic life in Athos, isolated from the rest of the world. The Athonite monasteries feature a rich collection of well-preserved artifacts, rare books, ancient documents, and artworks of immense historical value, and Mount Athos has been listed as a World Heritage site since 1988.

Although Mount Athos is legally part of the European Union like the rest of Greece, the Monastic State of the Holy Mountain and the Athonite institutions have a special jurisdiction which was reaffirmed during the admission of Greece to the European Community (precursor to the EU).[4] This empowers the Monastic State's authorities to regulate the free movement of people and goods in its territory; in particular, only males are allowed to enter.

Geography

The peninsula, the easternmost "leg" of the larger Chalkidiki peninsula in central Macedonia, protrudes 50 km (31 mi)[5] into the Aegean Sea at a width of between 7 and 12 km (4.3 and 7.5 mi) and covers an area of 335.6 km2 (130 sq mi). The actual Mount Athos has steep, densely forested slopes reaching up to 2,033 m (6,670 ft).

The surrounding seas, especially at the end of the peninsula, can be dangerous. In ancient Greek history two fleet disasters in the area are recorded: In 492 BC Darius, the king of Persia, lost 300 ships under general Mardonius.[6] In 411 BC the Spartans lost a fleet of 50 ships under admiral Epicleas.[7]

Though land-linked, Mount Athos is practically accessible only by boat. The Agios Panteleimon and Axion Estin ferries travel daily (weather permitting) between Ouranoupolis and Dafni, with stops at some monasteries on the western coast. There is also a smaller speed boat, the Agia Anna, which travels the same route, but with no intermediate stops. It is possible to travel by ferry to and from Ierissos for direct access to monasteries along the eastern coast.

Access

The number of daily visitors to Mount Athos is restricted, and all are required to obtain a special entrance permit valid for a limited period. Only men are permitted to visit the territory, which is called the "Garden of Virgin Mary" by the monks,[8] with Orthodox Christians taking precedence in permit issuance procedures. Residents on the peninsula must be men aged 18 and over who are members of the Eastern Orthodox Church and also either monks or workers.

As part of measures to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, visits to Mount Athos were suspended from 19–30 March 2020.[9]

History

Antiquity

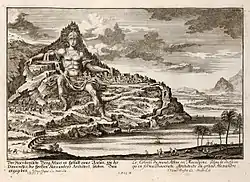

In Greek mythology, Athos is the name of one of the Gigantes that challenged the Greek gods during the Gigantomachia. Athos threw a massive rock against Poseidon which fell in the Aegean sea and became Mount Athos. According to another version of the story, Poseidon used the mountain to bury the defeated giant.

Homer mentions the mountain Athos in the Iliad.[10] Herodotus writes that, during the Persian invasion of Thrace in 492 BC, the fleet of the Persian commander Mardonius was wrecked with losses of 300 ships and 20,000 men, by a strong North wind while attempting to round the coast near Mount Athos.[11] Herodotus mentions the peninsula, then called Akte, telling us that Pelasgians from the island of Lemnos populated it and naming five cities thereon, Sane, Kleonai (Cleonae), Thyssos (Thyssus), Olophyxos (Olophyxus), and Akrothoon (Acrothoum).[12] Strabo also mentions the cities of Dion (Dium) and Akrothoon.[13] Eretria also established colonies on Akte. At least one other city was established in the Classical period: Akanthos (Acanthus). Some of these cities minted their own coins.

The peninsula was on the invasion route of Xerxes I, who spent three years[14] excavating the Xerxes Canal across the isthmus to allow the passage of his invasion fleet in 483 BC. After the death of Alexander the Great, the architect Dinocrates (Deinokrates) proposed carving the entire mountain into a statue of Alexander.

The history of the peninsula during latter ages is shrouded by the lack of historical accounts. Archaeologists have not been able to determine the exact location of the cities reported by Strabo. It is believed that they must have been deserted when Athos' new inhabitants, the monks, started arriving some time before the ninth century AD.[15]

Early Christianity

According to the Athonite tradition, the Blessed Virgin Mary was sailing accompanied by St John the Evangelist from Joppa to Cyprus to visit Lazarus. When the ship was blown off course to then-pagan Athos, it was forced to anchor near the port of Klement, close to the present monastery of Iviron. The Virgin walked ashore and, overwhelmed by the wonderful and wild natural beauty of the mountain, she blessed it and asked her Son for it to be her garden. A voice was heard saying, "Ἔστω ὁ τόπος οὗτος κλῆρος σὸς καὶ περιβόλαιον σὸν καὶ παράδεισος, ἔτι δὲ καὶ λιμὴν σωτήριος τῶν θελόντων σωθῆναι" (Translation: "Let this place be your inheritance and your garden, a paradise and a haven of salvation for those seeking to be saved"). From that moment the mountain was consecrated as the garden of the Mother of God and was out of bounds to all other women.[note 2]

Historical documents on ancient Mount Athos history are very few. It is certain that monks have been there since the fourth century, and possibly since the third. During Constantine I's reign (324–337) both Christians and pagans were living there. During the reign of Julian the Apostate (361–363), the churches of Mount Athos were destroyed, and Christians hid in the woods and inaccessible places.[16]

Later, during Theodosius I's reign (379–395), the pagan temples were destroyed. The lexicographer Hesychius of Alexandria states that in the fifth century there was still a temple and a statue of "Zeus Athonite". After the Islamic conquest of Egypt in the seventh century, many Orthodox monks from the Egyptian desert tried to find another calm place; some of them came to the Athos peninsula. An ancient document states that monks "built huts of wood with roofs of straw [...] and by collecting fruit from the wild trees were providing themselves improvised meals."[17]

Byzantine era: the first monasteries

The chroniclers Theophanes the Confessor (end of 8th century) and Georgios Kedrenos (11th century) wrote that the 726 eruption of the Thera volcano was visible from Mount Athos, indicating that it was inhabited at the time. The historian Genesios recorded that monks from Athos participated at the seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea of 787. Following the Battle of Thasos in 829, Athos was deserted for some time due to the destructive raids of the Cretan Saracens. Around 860, the famous monk Efthymios the Younger[18] came to Athos and a number of monk-huts ("skete of Saint Basil") were created around his habitation, possibly near Krya Nera. During the reign of emperor Basil I the Macedonian, the former Archbishop of Crete (and later of Thessaloniki) Basil the Confessor built a small monastery at the place of the modern harbour (arsanás) of Hilandariou Monastery. Soon after this, a document of 883 states that a certain Ioannis Kolovos built a monastery at Megali Vigla.

On a chrysobull of emperor Basil I, dated 885, the Holy Mountain is proclaimed a place of monks, and no laymen or farmers or cattle-breeders are allowed to be settled there. The next year, in an imperial edict of emperor Leo VI the Wise we read about the "so-called ancient seat of the council of gerondes (council of elders)", meaning that there was already a kind of monks' administration and that it was already "ancient". In 887, some monks expostulate to the emperor Leo the Wise that as the monastery of Kolovos is growing more and more, they are losing their peace.

In 908 the existence of a Protos ("First monk"), the "head" of the monastic community, is documented. In 943 the borders of the monastic state were precisely mapped; we know that Karyes was already the capital and seat of the administration, named "Megali Mesi Lavra" (Big Central Assembly). In 956, a decree offered land of about 940,000 m2 (230 acres) to the Xeropotamou monastery, which means that this monastery was already quite big.

In 958, the monk Athanasios the Athonite (Άγιος Αθανάσιος ο Αθωνίτης) arrived on Mount Athos. In 962 he built the big central church of the "Protaton" in Karies. In the next year, with the support of his friend Emperor Nicephorus Phocas, the monastery of Great Lavra was founded, still the largest and most prominent of the twenty monasteries existing today. It enjoyed the protection of the Byzantine emperors during the following centuries, and its wealth and possessions grew considerably.[19]

From the 10th to the 13th centuries, there was a Benedictine monastery on Mount Athos (between Magisti Lavra and Philotheou Karakallou[20]) known as Amalfion after the people of Amalfi who founded it.[21]

During the 11th century, Mount Athos offered a meeting place for Serbian and Russian monk Scribes. Russian monks first settled there in the 1070s, in Xylourgou Monastery (now Skiti Bogoroditsa); in 1089 they moved to the St. Panteleimon Monastery, while the Serbs took over the Xylourgou. From 1100 to 1169 the St. Panteleimon Monastery was in a state of decay and such Russian monks as remained in Mount Athos lived at Xylourgou among the Serbs. In 1169 the Serbs received St. Panteleimon, which they shared with the Russians until 1198, when the Serbs moved to the Hilandar monastery, which became the main centre of Serbian monasticism; the Russians then remained in possession of St. Panteleimon, known since as Rossikon.

The Fourth Crusade in the 13th century brought new Roman Catholic overlords, which forced the monks to complain and ask for the intervention of Pope Innocent III until the restoration of the Byzantine Empire. The peninsula was raided by Catalan mercenaries in the 14th century in the so-called Catalan vengeance due to which the entry of people of Catalan origin was prohibited until 2005. The 14th century also saw the theological conflict over the hesychasm practised on Mount Athos and defended by Gregory Palamas (Άγιος Γρηγόριος ο Παλαμάς). In late 1371 or early 1372 the Byzantines defeated an Ottoman attack on Athos.[19]

Serbian era and influences

Serbian lords of the Nemanjić dynasty offered financial support to the monasteries of Mount Athos, while some of them also made pilgrimages and became monks there. Stefan Nemanja helped build the Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos together with his son Archbishop Saint Sava in 1198.[22][23]

From 1342 until 1372 Mount Athos was under Serbian administration. Emperor Stefan Dušan helped Mount Athos with many large donations to all monasteries. In The charter of emperor Stefan Dušan to the Monastery of Hilandar[24] the Emperor gave to the monastery Hilandar direct rule over many villages and churches, including the church of Svetog Nikole u Dobrušti in Prizren, the church of Svetih Arhanđela in Štip, the Church of Svetog Nikole in Vranje and surrounding lands and possessions. He also gave large possessions and donations to the Karyes Hermitage of St. Sabas and the Holy Archangels in Jerusalem[25] and to many other monasteries. Dušan was the only medieval lord who spent a lot of his time in Mount Athos and at the same time from there ruled the Empire, spending 9 months there together with his wife around 1347. Empress Jelena, wife of the Emperor Stefan Dušan, was among the very few women allowed to visit and stay in Mount Athos.[26]

Thanks to the donations by Dušan, the Serbian monastery of Hilandar was enlarged to more than 10,000 hectares, thus having the largest possessions on Mount Athos among other monasteries, and occupying 1/3 of the area. Serbian nobleman Antonije Bagaš, together with Nikola Radonja, bought and restored the ruined Agiou Pavlou monastery between 1355 and 1365, becoming its abbot.[27]

The time of the Serbian Empire was a prosperous period for Hilandar and of other monasteries in Mount Athos and many of them were restored and rebuilt and significantly enlarged.[26] Donations continued after the fall of the Serbian empire and Lazar of Serbia and the later Branković dynasty continued to support the monastic community. Serbian magnate Radič (veliki čelnik) restored the Konstamonitou Monastery after the 1420 fire and then took monastic vows and received the name Roman (after 1433).

Serbian princess Mara Branković was the second Serbian woman that was granted permissions to visit area.[28] As a wife of Murad II, Mara Branković used her influence on the Ottoman court to secure the special status of Mount Athos inside the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the 15th century five monasteries on Mount Athos had Serbian monks and were under the Serbian Prior: Docheiariou, Grigoriou, Ayiou Pavlou, Ayiou Dionysiou and Hilandar[29]

Under Ottoman rule many Serbian nobles including ones who were under direct Ottoman rule or had accepted the Muslim faith continued their support for Mount Athos. In modern times after the end of Ottoman rule new Serbian kings from the Obrenović dynasty and Karađorđević dynasty and the new bourgeois class continued their support of Mount Athos. After the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia many presidents and prime ministers of Serbia visited Mount Athos.[30]

Ottoman era

The Byzantine Empire ceased to exist in the 15th century and the Ottoman Empire took its place.[31] The Athonite monks tried to maintain good relations with the Ottoman Sultans, and therefore when Murad II conquered Thessaloniki in 1430 they immediately pledged allegiance to him. In return, Murad recognized the monasteries' properties, something which Mehmed II formally ratified after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. In this way Athonite independence was preserved.

From the account of the Russian pilgrim Isaiah, by the end of the 15th century half of the monasteries were either Slav or Albanian. In particular, Docheiariou, Grigoriou, Ayiou Pavlou, Ayiou Dionysiou, and Chilandariou were Serbian; Karakalou and Philotheou were Albanian; Panteleïmon was Russian; Simonopetra was Bulgarian; Pantokratoros and Stavronikita were Greek; and Zographou, Kastamonitou, Xeropotamou, Koutloumousiou, Xenophontos, Iviron and Protaton did not bear any designation.[32]

The 15th and 16th centuries were particularly peaceful for the Athonite community. This led to relative prosperity for the monasteries. An example of this is the foundation of Stavronikita monastery which completed the current number of Athonite monasteries. Following the conquest of the Serbian Despotate by the Ottomans many Serbian monks came to Athos. The extensive presence of Serbian monks is depicted in the numerous elections of Serbian monks to the office of the Protos during the era.

Sultan Selim I was a substantial benefactor of the Xeropotamou monastery. In 1517, he issued a fatwa and a Hatt-i Sharif ("noble edict") that "the place, where the Holy Gospel is preached, whenever it is burned or even damaged, shall be erected again." He also endowed privileges to the Abbey and financed the construction of the dining area and underground of the Abbey as well as the renovation of the wall paintings in the central church that were completed between the years 1533–1541.[33]

Although most time the monasteries were left on their own, the Ottomans heavily taxed them and sometimes they seized important land parcels from them. This eventually culminated in an economic crisis in Athos during the 17th century. This led to the adoption of the so-called "idiorrhythmic" lifestyle (a semi-eremitic variant of Christian monasticism) by a few monasteries at first and later, during the first half of the 18th century, by all.

This new way of monastic organization was an emergency measure taken by the monastic communities to counter their harsh economic environment. Contrary to the cenobitic system, monks in idiorrhythmic communities have private property, work for themselves, they are solely responsible for acquiring food and other necessities and they dine separately in their cells, only meeting with other monks at church. At the same time, the monasteries' abbots were replaced by committees and at Karyes the Protos was replaced by a four-member committee.[34]

In 1749, with the establishment of the Athonite Academy near Vatopedi monastery, the local monastic community took a leading role in the modern Greek Enlightenment movement of the 18th century.[35] This institution offered high level education, especially under Eugenios Voulgaris, where ancient philosophy and modern physical science were taught.[36]

Russian tsars, and princes from Moldavia, Wallachia and Serbia (until the end of the 15th century), helped the monasteries survive with large donations. The population of monks and their wealth declined over the next centuries, but were revitalized during the 19th century, particularly by the patronage of the Russian government. As a result, the monastic population grew steadily throughout the century, reaching a high point of over 7,000 monks in 1902.

In November 1912, during the First Balkan War, the Ottomans were forced out by the Greek Navy.[37] Greece claimed the peninsula as part of the peace treaty of London signed on 30 May 1913. As a result of the shortcomings of the Treaty of London, the Second Balkan War broke out between the combatants in June 1913. A final peace was agreed at the Treaty of Bucharest on 10 August 1913.

In June 1913, a small Russian fleet, consisting of the gunboat Donets and the transport ships Tsar and Kherson, delivered the archbishop of Vologda, and a number of troops to Mount Athos to intervene in the theological controversy over imiaslavie (a Russian Orthodox movement).

The archbishop held talks with the imiaslavtsy and tried to make them change their beliefs voluntarily, but was unsuccessful. On 31 July 1913, the troops stormed the St. Panteleimon Monastery. Although the monks were not armed and did not actively resist, the troops showed very heavy-handed tactics. After the storming of St. Panteleimon Monastery, the monks from the Andreevsky Skete (Skiti Agiou Andrea) surrendered voluntarily. The military transport Kherson was converted into a prison ship and more than a thousand imiaslavtsy monks were sent to Odessa where they were excommunicated and dispersed throughout Russia.

After a brief diplomatic conflict between Greece and Russia over sovereignty, the peninsula formally came under Greek sovereignty after World War I.

See also

Notes

- Drachma before 2001.

- St Gregory Palamas included this tradition in his book Life of Petros the Athonite, p. 150, 1005 AD.

References

- "Σύνταγμα της Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας" (PDF). hellenicparliament.gr. 1927. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "The Protaton church at Karyes". Macedonian-heritage.gr. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- "Mount Athos Home". Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Official Journal of the European Communities: L 291 - Volume 22 - 19 November 1979". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Robert Draper, "Mount Athos" Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, National Geographic magazine, December 2009

- Herodotus, Histories, book VI ("Erato"); Aeschylus, The Persians.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica XIII 41, 1–3.

- Athonite monasticism at the dawn of the third millennium, Pravmir Portal, September 2007.

- James J. Williams. "Coronavirus: Mount Athos Closes for Pilgrims and Visitors until March 30", Belle News, 20 March 2020. Retrieved on 20 March 2020.

- Homer, Iliad 14,229.

- Herodotus, Histories 6,44.

- Herodotus, Histories 7,22.

- Strabo, Geography 7,33,1.

- Warry, J. 1998 Warfare in the Classical World Salamander Book Ltd., London p 35

- Kadas, Sotiris. The Holy Mountain (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. p. 9. ISBN 978-960-213-199-2.

- Speake 2002, p. 27.

- Biography of Saint Athanasius the Athonite

- Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed. (2005). "Euthymios the Younger". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

also called Euthymios of Thessalonike, saint; baptismal name Niketas; born village of Opso, Galatia 823/4

- Fine, John (1987). The Late Medieval Balkans. University of Michigan Press. pp. 381. ISBN 978-0-472-10079-8.

- https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2010/07/amalfion-benedictine-monastery-on-mount.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120112043133/http://allmercifulsavior.com/Liturgy/Amalfion%20Oct%202002.pdf

- 100 najznamenitijih Srba. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 1993. ISBN 978-86-82273-08-0.; 1st place

- Mileusnić 2000, p. 38.

- Komatina, Ivana. "I. Komatina, Povelja cara Stefana Dušana manastiru Hilandaru (The charter of emperor Stefan Dušan to the Monastery Hilandar), SSA 13 (2014)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Serbian Church in History". atlantaserbs.com.

- ([email protected]), Veselin Ostojin ([email protected]), Jasmina Maric. "Srpsko Nasledje". srpsko-nasledje.rs.

- Angold, Michael (17 August 2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521811132 – via Google Books.

- "SERBIA". fmg.ac.

- Bakalopulos, A. E. (11 April 1973). "History of Macedonia, 1354–1833. [By] A.E. Vacalopoulos" – via Google Books.

- Pešić, Milenko. "Blagoslov Hilandara za kraljeve i predsednike".

- John Anthony McGuckin (15 December 2010). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Byzantine political influence was effectively ended, but the prerogatives of the Greek Church remained and were amalgamated by the Sultans.

- Vacalopoulos, A.E. (1973). History of Macedonia, 1354–1833. pp. 166–167.

At the end of the 15th century, the Russian pilgrim Isaiah relates that the monks support themselves with various kinds of work including the cultivation of their vineyards....He also tells us that nearly half the monasteries are Slav or Albanian. As Serbian he instances Docheiariou, Grigoriou, Ayiou Pavlou, a monastery near Ayiou Pavlou and dedicated to St. John the Theologian (he no doubt means the monastery of Ayiou Dionysiou), and Chilandariou. Panteleïmon is Russian, Simonopetra is Bulgarian, and Karakallou and Philotheou are Albanian. Zographou, Kastamonitou (see fig. 58), Xeropotamou, Koutloumousiou, Xenophontos, Iveron and Protaton he mentions without any designation; while Lavra, Vatopedi (see fig. 59), Pantokratoros, and Stavronikita (which had been recently founded by the patriarch Jeremiah I) he names specifically as being Greek (see map 6).

- Municipality of Stagira, Acanthos Archived 27 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Kadas, Sotiris. The Holy Mountain (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-960-213-199-2.

- Facaros, Dana; Theodorou, Linda (2003). Greece. New Holland Publishers. p. 578. ISBN 978-1-86011-898-2.

- Scupoli, Lorenzo; Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain (1978). Unseen warfare: the Spiritual combat and Path to paradise of Lorenzo Scupoli. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-913836-52-1.

- "The Famous Abode of Monks in Greek Hands". London Standard. London. 16 November 1912. p. 9.

Bibliography

- Holy Mountain. Stone Arched Bridges and Aqueducts (ISBN 978-618-00-0827-2) by Frangiscos Martinos. Edited by Dimitri Michalopoulos (Athens, 2019).

- Mount Athos ISBN 960-213-075-X by Sotiris Kadas. An illustrated guide to the monasteries and their history (Athens 1998). With many illustrations of the Byzantine art treasures on Mount Athos.

- Athos The Holy Mountain by Sydney Loch. Published 1957 & 1971 (Librairie Molho, Thessaloniki). Loch spent most of his life in the Byzantine tower at Ouranopolis, close to Athos, and describes his numerous visits to the Holy Mountain.

- The Station: Athos: Treasures and Men by Robert Byron. First published 1931, reprinted with an introduction by John Julius Norwich, 1984.

- Dare to be Free ISBN 0-330-10629-5 by Walter Babington Thomas. Offers insights into the lives of the monks of Mt Athos during World War II, from the point of view of an escaped POW who spent a year on the peninsula evading capture.

- Blue Guide: Greece ISBN 0-393-30372-1, pp. 600–03. Offers history and tourist information.

- Mount Athos: Renewal in Paradise ISBN 978-0300093537, by Graham Speake. Published by Yale University Press in 2002. An extensive book about Athos in the past, the present and the future. Includes valuable tourist information. Features numerous full-colour photographs of the peninsula and daily life in the monasteries. 2nd edition published by Denise Harvey in 2014, which includes revisions, updates, and a new chapter documenting the changes that have occurred in the twelve years since its first publication.

- From the Holy Mountain by William Dalrymple. ISBN 0-8050-6177-0. Published 1997.

- Ульянов О. Г. The influence of the monasticism of Holy Mount Athos on the liturgical reform movement in the Late Byzantine // Church, Society and Monasticism. The second international monastic symposium at Sant’Anselmo. Roma, 2006.

- Ivanov, Emil: Das Bildprogramm des Narthex im Rila-Kloster in Bulgarien unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Wasserweihezyklen auf dem Athos, Diss., Erlangen, 2002.

- Ivanov, Emil: Apokallypsedarstellungen in der nachbyzantinischen Kunst, in: Das Münster, 3, 2002, 208–217.

- "Mount Athos". National Geographic. Vol. 164 no. 6. December 1983. pp. 738–766. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (2000) [1989]. Sveti Srbi (in Serbian). Novi Sad: Prometej. ISBN 978-86-7639-478-4. OCLC 44601641.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mount Athos. |