Moscopole

Moscopole (Albanian: Voskopojë; Aromanian: Moscopole, Moscopoli, Muscopuli, Voscopole; Greek: Μοσχόπολη or Βοσκόπολη; Turkish: İskopol or Oskopol[1]) is a village in Korçë County in southeastern Albania. During the 18th century, it was the cultural and commercial center of the Aromanians.[2] At its peak, in the mid 18th century, it hosted the first printing press in the Ottoman Balkans outside Istanbul, educational institutions and numerous churches[3] and became a leading center of Greek culture.[4][5]

Voskopojë

Moscopole Moscopoli Muscopuli Voscopole Moschopolis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

Voskopojë | |

| Coordinates: 40°38′0″N 20°35′25″E | |

| Country | |

| County | Korçë |

| Municipality | Korçë |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Municipal unit | 1,058 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal Code | 7029 |

| Area Code | 0864 |

| Website | www.voskopoja.al |

Historians have attributed the decline of the city to a series of raids by Muslim Albanian bandits.[6][7] Moscopole was initially attacked and almost destroyed by those groups in 1769 following the participation of the residents in the preparations for a Greek revolt supported by the Russian Empire.[8] Its destruction culminated with the abandoning and destruction of 1788.[9][10][6] Moscopole, once a prosperous city, was reduced to a small village by Ali Pasha. According to another opinion, the city's decline was mainly due to the relocation of the trade routes in central and eastern Europe following these raids.[8] Today Moscopole, known as Voskopojë, is a small mountain village, and along with a few other local settlements is considered a holy place by local Orthodox Christians. It was one of the original homelands of the Aromanian diaspora.[11]

Geography

Modern Voskopojë is located 21 km from Korçë, in the mountains of southeastern Albania, at an altitude of 1160 meters, and is a subdivision of Korçë municipality;[12][13] its population in 2011 was 1,058.[14] The municipality of Voskopojë consists of the villages of Voskopojë, Shipskë, Krushovë, Gjonomadh and Lavdar.[15] In 2005, the municipality had a population of 2,218,[16] whereas the settlement itself has a population of around 500.[12]

History

Demographics

Although located in a rather isolated place in the mountains of southern Albania, the city rose to become the most important center of the Aromanians. It was a small settlement until the end of the 17th century, but afterwards showed a remarkable financial and cultural development.[8] Some writers have claimed that Moscopole in its glory days (1730–1760) had as many as 70,000 inhabitants; other estimates placed its population closer to 35,000;[17][18] but a more realistic number may be closer to 3500: "...The truth may be closer to this number [sc. 3500] than to 70,000. Moschopolis was certainly not among the largest Balkan cities of the 18th century".[19]

According to the Swedish historian Johann Thunmann, who visited Moscopole and wrote a history of the Aromanians in 1774, everyone in the city spoke Aromanian; many also spoke Greek, which was used for writing contracts, in fact the city is said to have been mainly populated by Vlachs/Aromanians. The fact was confirmed by a 1935 analysis of the family names shows that the majority of the population were indeed Vlachs, but there were also Greeks and Albanians present in the city.[20]

Economy

Historically the main economic activity of the city was the livestock farming. The alternative name "Voskopolis" means "City of shepherds".[21] This activity led to the establishment of wool processing and carpet manufacturing units and the development of tanneries, while other locals became metal workers, silver and copper smiths.[8] During the middle of the 18th century, the city became an important economic center whose influence spread over the boundaries of the Archbishopric of Ohrid, and reached further the Ottoman ruled Eastern-Orthodox world: the trade involved as far as the Archduchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Hungary, and the Upper Saxony. Until 1769, the town traded on a large scale with renowned European commercial centres of that time, such as Venice, Vienna and Leipzig.[22]

Culture

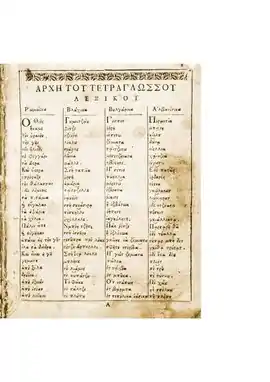

A printing press was also operating in Moscopole which was the second one in Ottoman Europe (in Turkish: İskopol/Oskopol,[1]) after that of Constantinople. This establishment produced a total of nineteen books, mainly Services to the Saints but also the Introduction of Grammar by the local scholar Theodore Kavalliotis.[8] The later became director of the city's prestigious educational institution, which from 1744 was known as New Academy or Hellenikon Frontistirion, sponsored by the wealthy merchants of the diaspora. Moreover, the city hosted an orphanage, known as Orphanodioiketerion, probably the first in the post-Byzantine Orthodox world,[23] a hospital and a total of 24 churches.[12]

A cultural effervescence arose in Moscopole, and many authors published their works in both the Greek language (which was the language of culture of the Balkans at the time) and Aromanian, written in the Greek alphabet. In 1770, the first dictionary of four modern Balkan languages (Greek, Albanian, Vlach/Aromanian and Bulgarian) was published here. Daniel Moscopolites a Vlach-speaking native priest of Moscopole, compiled a quadrilingual lexicon of Greek, Vlach, Bulgarian and Albanian, that aimed at the hellenization of the non-Greek-speaking Christian communities in the Balkans.[24][25] Due to the high level of intellectual activity and Greek education Moscopole was nicknamed as New Athens or New Mystra.[26][27] As such the city became an important 18th century center of the modern Greek Enlightenment.[28][29]

Decline

The 1769 sacking and pillaging by Muslim Albanian[20] troops was just the first of a series of attacks. Moscopole was attacked due to the participation of the residents in the preparations for a Greek revolt supported by the Russian Empire (known as Orlov revolt).[8] Its destruction culminated with the razing of 1788 by the troops of Ali Pasha.[38] Moscopole was practically destroyed by this attack, while some of its commerce shifted to nearby Korçë and Berat.[39]

The survivors were thus forced to flee, most of them emigrating mainly to Thessaly and Macedonia. Some of the commercial elite moved to the Archduchy of Austria, and the Kingdom of Hungary especially to the respective capitals of Vienna and Budapest, but also to Transylvania, where they had an important role in the early National awakening of Romania. The city never rose back to its earlier status. However, a new school was established at the end of the 18th century whose headmaster in 1802 was Daniel Moscopolites. This school functioned the following decades, thanks to donations and bequests by baron Simon Sinas, a member of the diaspora.[40]

In 1900, a report by the Greek consul Betsos gave details of the demographic composition of Moscopole.[41] It noted that the 18th century destruction of the settlement resulted in the dispersal of its Aromanian speaking population and the some old remaining families moved to other places, in particular Korçë.[41] Around 30 old families remained, however the socio-political crisis that engulfed the nearby Opar region resulted in Albanian speaking Christians leaving their previous homes and resettling in Moscopole.[41] Aromanians from two nearby settlements also resettled in Moscopole.[41] Moscopole in 1900 was populated by a total of 200 families, consisting of 120 Albanian speaking and 80 Aromanian speaking families.[41] Most of the older Aromanian speaking families had a Greek national consciousness while 3 families along with some of the newer residents were pro-Romanian (a total of 20 families), led by an unfrocked priest named Kosmas.[41]

In 1914 Moscopole was part of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus. It was destroyed again in 1916 during World War I by the marauding Albanian bands of Sali Butka.[42]

During the Greco-Italian War, on 30 November 1940, the town was controlled by the advancing Greek forces.[43] In April 1941, after the capitulation of Greece, Moscopole returned to Axis control. The remaining buildings were razed three times during the partisan warfare of World War II: once by Italian troops and twice by the Albanian nationalist Balli Kombëtar organization.[44] Of the old city, six Orthodox churches (one in a very ruined state), a bridge and a monastery survive. In 1996, the church of St. Michael was vandalized by three adolescent Albanians under the influence of a foreign Muslim fundamentalist.[18] In 2002, the five standing churches were put on the World Monuments Fund's Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites

Modern town

Today, Moscopole is just a small mountain village and ski resort.[45] Nonetheless, memories of glory days of Moscopole remain an important part of the culture of the Aromanians.

During recent years, a Greek language institution, a joint Greek-Albanian initiative, has operated in Moscopole.[46]

Moscopole, known in Albania as being a traditionally Christian settlement is neighbours with various Muslim and Christian Albanian villages that surround it, although the latter have become "demographically depressed", due to migration.[47] During the communist period some Muslim Albanians from surrounding villages settled in Moscopole making locals view the village population as mixed (i përzier) and lamenting the decline of the Christian element.[47]

| Part of a series on |

| Aromanians |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Major settlements |

| Language and identity |

| Religion |

| History |

| Related groups |

Orthodox churches and monasteries

The remaining churches in the region are among the most representative of 18th century ecclesiastical art in the Balkans. Characteristically, their murals are comparable to that in the large monastic centres at Mount Athos and Meteora in Greece. The architectural design is in general specific and identical: a large three-aisled basilica with a gable roof. The churches are single-apsed, with a wide altar apse and internal niches that serve as prothesis and diaconicon. Most churches also have one niche, each on the northern and southern walls, next to the prothesis and the diaconicon. Along the southern side there is an arched porch.[22]

Of the ca. 24–30 churches of Moscopole, besides the St. John the Baptist Monastery (Albanian: Manastiri i Shën Prodhromit, Greek: Μονή Αγίου Ιωάννου του Προδρόμου) in the vicinity of the town,[22] only five have survived into modern times:

- Saint Nicholas (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Kollit, Greek: Ναός Αγίου Νικολάου)

- Dormition of the Theotokos (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Mërisë, Greek: Ναός Κοιμήσεως της Θεοτόκου)

- Saint Athanasius (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Thanasit, Greek: Ναός Αγίου Αθανασίου)

- Saint Michael or Archangels Michael and Gabriel (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Mëhillit, Greek: Ναός Αγίων Ταξιαρχών)

- Saint Elijah (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Ilias, Greek: Ναός Προφήτη Ηλία)

Some of the ruined churches include the following:

- Saint Paraskevi (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Premtes, Greek: Ναός Αγίας Παρασκευής), patron saint of the town and probably the first church built in Moscopole in the 15th century.[48]

- Saint Charalampus (Albanian: Kisha e Shën Harallambit, Greek: Ναός Αγίου Χαραλάμπους), outer walls partially survived

- Saint Euthymius, completely destroyed.[22]

Climate

There is a combination of mild valley climate in the lower parts and true Alpine climate in the higher regions. Favorable climate conditions make this center ideal for winter, summer, sport, recreation tourism, so there are tourists during the whole year, not only from areas of Albania, but also foreigners.[49]

Moscopolites

- Ioannis Chalkeus, Aromanian scholar and philosopher

- Theophrastos Georgiadis, Greek author and teacher

- Daniel Moscopolites, Aromanian Greek scholar

- Theodore Kavalliotis, Greek Aromanian priest and teacher

- Dionysios Mantoukas, Orthodox bishop

- Ioakeim Martianos, Orthodox bishop

- Sinas family (notable members of this family were: Georgios Sinas and Simon Sinas), Greek bankers

- Nektarios Terpos, Greek religious scholar and monk

- Konstantinos Tzechanis, Greek or Aromanian or Albanian philosopher, mathematician and poet

Gallery

Tourist center

Tourist center.jpg.webp) Mountains near Moscopole

Mountains near Moscopole Macedonian Aromanian festival in Moscopole

Macedonian Aromanian festival in Moscopole View of the village

View of the village Saint Nicholas church

Saint Nicholas church Saint Nicholas church

Saint Nicholas church Arched bridge next to the village

Arched bridge next to the village

See also

References

- Anscombe, Frederick (2006). "Albanians and "mountain bandits"". In Anscombe, Frederick. The Ottoman Balkans, 1750–1830. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 99. "İskopol/Oskopol (Voskopoje, southeast Albania"

- Förster Horst, Fassel Horst. Kulturdialog und akzeptierte Vielfalt?: Rumänien und rumänische Sprachgebiete nach 1918.. Franz Steiner Verlag, 1999. ISBN 978-3-7995-2508-4, p. 33: "Moschopolis zwar eine aromunische Stadt ... deren intelektuelle Elite in starken Masse graekophil war."

- Rousseva R. Iconographic characteristics of the churches in Moschopolis and Vithkuqi (Albania), Makedonika, 2006, v. 35, pp. 163–191. Archived 4 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine In English and Greek, with photographs of icons and inscriptions.

- Cohen, Mark (2003). Last century of a Sephardic community: the Jews of Monastir, 1839–1943. Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-886857-06-3.

Moschopolis emerged as the leading center of Greek intellectual activity in the 18th

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands, borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. Duckworth. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-7156-3201-7.

- Vickers, Miranda (1995). The Albanians: A Modern History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780857736550.

- Cohen, Mark (2003). Last century of a Sephardic community : the Jews of Monastir, 1839–1943. New York: Foundation for the advancement of Sephardic studies and culture. ISBN 9781886857063.

In 1769, and then again in 1788, this thriving town was sacked by Muslim Albanians. It was finally destroyed in the early 19th century by Ali Pasha...

- Mikropoulos, Tassos A. (2008). Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. pp. 315–316. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- Hermine G. De Soto, Nora Dudwick. Fieldwork dilemmas: anthropologists in postsocialist states. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-299-16374-7, p. 45.

- Mackridge, Peter (2 April 2009). Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766–1976. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-921442-6.

- Gilles de Rapper. Religion on the border: Sanctuaries and festivals in post-communist Albania. Religion on the Boundary and the Politics of Divine Interventions. Proceedings of the International Conference, Sofia 14–18 April 2006. Istanbul, Isis Press, p. 5.

- Marcel Cornis-Pope; John Neubauer (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 90-272-3453-1.

- "Law nr. 115/2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- 2011 census results Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Greece – Albania Neighbourhood Programme Archived 27 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Albania Communes". World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- Peyfuss, p. 35-36 snippet view

- Robert Elsie's review on Peyfuss"Peyfuß, Max Demeter: Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769. Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung im Erzbistum Achrida" (PDF). Elsie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2005.

- Max Demeter Peyfuss. Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769: Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung im Erzbistum Achrida. Böhlau, 1989, ISBN 978-3-205-05293-7, p. 35–36

- Stavrianos Leften Stavros, Stoianovich Traian. The Balkans since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-1-85065-551-0, p. 278.

- Geographikon tēs Rhumanias: es akribesteran kai plēresteran katalēpsin tēs historias autēs. Tauchnitz. 1816. p. 35.

- Kirchhainer, Karin (2003). "Iconographic Characteristics of the Churches in Moschopolis and Vithikuqi (Albania)" (PDF). Makedonika. 35 (4): 163–191.

- Anthony L. Scott (2003). Good and Faithful Servant: Stewardship in the Orthodox Church. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-88141-255-0.

- Friedman A. Victor. After 170 years of Balkan linguistics. Wither the Millennium? University of Chicago. p. 2: "...given the intent of these comparative lexicons was the Hellenization of non-Greek-speaking Balkan Christians...

- Horst Förster; Horst Fassel (1999). Kulturdialog und akzeptierte Vielfalt?: Rumänien und rumänische Sprachgebiete nach 1918. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 35, 45. ISBN 978-3-7995-2508-4.

- Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. Duke University. 1981.

- Asterios I. Koukoudēs. The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. 2003.

- Goldwyn, Adam J.; Silverman, Renée M. (2016). Mediterranean Modernism: Intercultural Exchange and Aesthetic Development. Springer. p. 177. ISBN 9781137586568.

...with Moschopolis we get a perspective on the Balkans, Greek enlightenment and the eighteent century...

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M. (2013). Enlightenment and Revolution. Harvard University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780674726413.

Besides the triangle... with a northwestern outpost in Moschopolis), where the first drama of the Enlightenment ...

- Multiculturalism, alteritate, istoricitate «Multiculturalism, Historicity and "The image of the Other"» by Alexandru Niculescu, Literary Romania (România literară), issue: 32 / 2002, pages: 22,23,

- Angeliki Konstantakopoulou, Η ελληνική γλώσσα στα Βαλκάνια 1750–1850. Το τετράγλωσσο λεξικό του Δανιήλ Μοσχοπολίτη [The Greek language in the Balkans 1750–1850. The dictionary in four languages of Daniel Moschopolite]. Ioannina 1988, 11.

- Peyfuss, Max Demeter: Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769. Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung im Erzbistum Achrida. Wien – Köln 1989. (Wiener Archiv f. Geschichte des Slawentums u. Osteuropas. 13), ISBN 3-205-98571-0.

- Kahl, Thede: Wurde in Moschopolis auch Bulgarisch gesprochen? In: Probleme de filologie slavă XV, Editura Universităţii de Vest, Timişoara 2007, S. 484–494, ISSN 1453-763X.

- Multiculturalism, alteritate, istoricitate «Multiculturalism, Historicity and "The image of the Other"» by Alexandru Niculescu, Literary Romania (România literară), issue: 32 / 2002, pages: 22,23,

- Angeliki Konstantakopoulou, Η ελληνική γλώσσα στα Βαλκάνια 1750–1850. Το τετράγλωσσο λεξικό του Δανιήλ Μοσχοπολίτη [The Greek language in the Balkans 1750–1850. The dictionary in four languages of Daniel Moschopolite]. Ioannina 1988, 11.

- Peyfuss, Max Demeter: Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769. Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung im Erzbistum Achrida. Wien – Köln 1989. (Wiener Archiv f. Geschichte des Slawentums u. Osteuropas. 13), ISBN 3-205-98571-0.

- Kahl, Thede: Wurde in Moschopolis auch Bulgarisch gesprochen? In: Probleme de filologie slavă XV, Editura Universităţii de Vest, Timişoara 2007, S. 484–494, ISSN 1453-763X.

- Katherine Elizabeth Fleming. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4, p. 36 "...destroyed by resentful Muslim Albanians in 1788"

- Princeton University. Dept. of Near Eastern Studies. Princeton papers: interdisciplinary journal of Middle Eastern studies. Markus Wiener Publishers, 2002. ISSN 1084-5666, p. 100.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotikē Athēnōn. p. 308. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- Koukoudis, Asterios (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Thessaloniki: Zitros Publications. pp. 362–363. ISBN 9789607760869. "A report by Betsos, the Greek consul in Monastir, is very informative about the demographic composition of Moschopolis in 1900. Moscopolis: The old Vlach-speaking inhabitants of Moscopolis dispersed in all directions at the end of the eighteenth century, because the Moslem Albanians living round about pillages that once famed city, and the comparatively few remaining families gradually moved elsewhere, particularly to Korçë, which slowly became an important commercial centre. Of the old Vlach families, only about thirty remain in Moscopolis; but on the other hand, the widespread disorder ravaging the area of Opar has caused many Albanian speaking families to leave the barren, mountainous parts of the country and remove to Moscopolis, where they till the land and raise livestock. Able Vlach-speaking families came from two Vlach settlements to Moscopolis, of which the entire population at present amounts to 200 families, of which 120 are Albanian-speaking and the remaining 80 Vlach speaking. All the old Vlach-speaking families have remained true to [their Greek national consciousness], but for three, who, together with some of the newcomers, have been led astray by the unfrocked priest Kosmas. The Romanising families there number twenty in all."

- Badlands, borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. Tom Winnifrith. Duckworth, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7156-3201-7, p. 61.

- Creveld, Martin L. van (1973). Hitler's strategy 1940–1941 : the Balkan clue (Reprinted. ed.). London: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 9780521201438.

Moschopolis and Pogradec fell on 30 November

- Pyrrhus J., Ruches (1965). "Albania's Captives". Chicago: Argonaut: 213.

Burned once by the Italians, twice by the Ballists... led by Dervish Bejo by Georgevitsa.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Golka, Vasjan (17 November 2008). "Korca Te dhena te pergjithshme" (PDF). Korca Jone Portal. p. 7.

- Καγιά, Έβις (2006). Το Ζήτημα της Εκπαίδευσης στην Ελληνική Μειονότητα και οι Δίγλωσσοι Μετανάστες Μαθητές στα Ελληνικά Ιδιωτκά Σχολεία στην Αλβανία (in Greek). University of Thessaloniki. pp. 118–121. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- De Rapper, Gilles (2010). "Religion on the border: sanctuaries and festivals in post-communist Albania": 3.

The three villages are known as Christians villages where Muslims have recently settled, especially during communist times, so that today their population is said to be 'mixed' (i përzier). They are also surrounded by Muslim villages, or by demographically depressed Christian villages; in other words, from the Christian point of view, the villages and their surroundings have lost a part of their Christian character. In the case of Voskopojë and Vithkuq, this loss is told in a more dramatic mode: both villages are known to have been prosperous Christian cities in the 18th century, before they were plundered and destroyed during repeated attacks by local Muslims.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Koukoudis, Asterios I. (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Zitros. p. 13. ISBN 978-960-7760-86-9.

- Vassilis Nitsiakos (October 2010). On the Border: Transborder Mobility, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries Along the Albanian-Greek Frontier. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 373. ISBN 978-3-643-10793-0.

Sources

- Asterios Koukoudis Studies on the Vlachs (in Greek and English)

- Românii din Albania – Aromânii(in Romanian)

- Steliu Lambru, Narrating National Utopia – The Case Moschopolis in the Aromanian National Discourse (in English)

- Peyfuss, Max Demeter (1989). Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769: Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung im Erzbistum Achrida (in German). Vienna: Böhlau. ISBN 3-205-98571-0.

- Nicolas Trifon, Des Aroumains aux Tsintsares - Destinées Historiques Et Littéraires D’un Peuple Méconnu (in French)

- Ewa Kocój, The Story of an Invisible City. The Cultural Heritage of Moscopole in Albania. Urban Regeneration, Cultural Memory and Space Management [in:] Intangible heritage of the City. Musealisation, preservation, education, ed. By M. Kwiecińska, Kraków 2016, s. 267-280

External links

- Adhami, Stilian (1989). Voskopoja: në shekullin e lulëzimit të saj (in Albanian). Tirana, Albania: 8 Nentori. p. 222.

- Falo, Dhari (2002). "Trayedia ali Muscopuli" (in Aromanian). Cartea aromână. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Γεωργιάδης, Θεόφραστος (1975). Moschopolis Μοσχόπολις (in Greek). Έκδοσις Συλλόγου προς Διάδοση των Ελληνικών Γραμμάτων.

- Plasari, Aurel]] (2000). "Fenomeni Voskopoje". Mendimi Shqiptar (in Albanian). Phoenix (6): 100.

- Robert Elsie, Eifel Olzheim. Review: Peyfuß, Max Demeter: Die Druckerei von Moschopolis, 1731–1769. Buchdruck und Heiligenverehrung im Erzbistum Achrida.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moscopole. |