Matthew McClung

Matthew Henry McClung Jr. (December 1, 1868 – March 3, 1908), sometimes referred to as Dibby McClung, was an American college football player, coach, and official. Born into a powerful southern family, McClung was raised in Memphis, Tennessee until he was accepted into Lehigh University. Immediately establishing himself as a skilled sportsman, McClung participated on both the school's football and baseball teams. He served as captain of the former in 1892 and is credited with turning it into one of the school's best ever football squads. McClung graduated from Lehigh in 1893 with degrees in metallurgy and mining engineering.

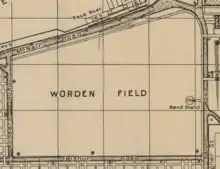

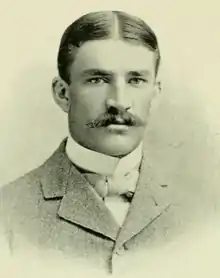

McClung from the 1898 Epitome | |

| Biographical details | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 1, 1868 Knoxville, Tennessee |

| Died | March 3, 1908 (aged 39) Joliet, Illinois |

| Playing career | |

| Football | |

| 1890–1893 | Lehigh |

| Position(s) | Quarterback |

| Coaching career (HC unless noted) | |

| Football | |

| 1894–1895 | Lehigh (assistant) |

| 1895 | Navy |

| Baseball | |

| 1895 | Lehigh |

| Head coaching record | |

| Overall | 5–2 (football) 8–12 (baseball) |

After graduating, McClung took a position as the coach of the Naval Academy football team. He served for one season, leading the team to a 5-2 record against a mediocre schedule. Following the season, he began a career as a college football referee which would span twelve years.[1]

Early life and college

All-American Yale quarterback John de Saulles, remembering visiting Lehigh in 1889[2]

Matthew McClung was born on December 1, 1868, the fifth of seven children between Matthew McClung Sr. and Julia Frances Anderson. The younger McClung was raised in Knoxville, Tennessee, where both of his parents' families were well established.[3] McClung entered Lehigh University in 1889, majoring in mining engineering and metallurgy; the classes were held by students to be the hardest at the university.[3][4] He joined the school's chapter of the Psi Upsilon fraternity, one of nine freshmen to be accepted In Universitate.[5] He also became a member of one of the school's several clubs, the "Aetos Club", which he represented in intramural athletics.[6] McClung immediately made his athletic presence at the school known, joining the lawn tennis team and the freshman baseball team as a left fielder; he also won the university's baseball-throwing competition.[7] He was starting catcher for the 1889 baseball team that went 4-7-1 and played in approximately one quarter of a football game.[8] McClung completed his first year by toasting for the university's fraternities at the year's freshman banquet.[9]

McClung's sophomore year remained largely the same as his freshman one. He maintained membership with the Psi Upsilon and the Aetos Club, but he also joined the university's Southern Club, German club, and its Chemical and Natural History Society.[10][11] He shifted from being the baseball team's catcher to center fielder, where he played in twelve out of twenty games. McClung had the third worst batting stats of anyone on the team, getting only nine hits on fifty-seven at-bats. He was also named starting quarterback of the school's football team and led the squad to a 6-4 record, which included two wins over rival Lafayette.[12]

Career

Football coach

Following his graduation, McClung remained at Lehigh, assisting in coaching the school's 1894 season. In 1895, McClung was hired by the United States Naval Academy to replace William Wurtenburg as the head coach of their football program. McClung was the fifth football coach for the school in as many years. He took over during a period at the Academy when, according to historian Morris Allison Bealle, "football was waning in Annapolis" and that "there was no climax incentive to steam up players".[14] McClung scheduled seven games for the 1895 season, three of which were simply squads from nearby athletic clubs. He hired Paul Dashiell, a former teammate of his at Lehigh, as his assistant coach for the year.[15] His team played at home for the entire season, due to restrictions put forth by president Grover Cleveland following the bloody 1893 Army-Navy Game. McClung's squad began the season with wins over two of the athletic clubs by a combined score of 40-0. These wins were followed by consecutive shutouts of Franklin & Marshall and Carlisle.[15] Virginia was the next team on Navy's schedule, but their opponents were forced to forfeit the match after a fire destroyed one of the campus's major structures.[18][19] McClung's team finished their season with two consecutive close losses to the Orange Athletic Club and his former team, Lehigh.[15] He did not return to coach the following year's squad; instead, the job went to Princeton dropout Johnny Poe.[20] Because of McClung's scheduling, the Naval Academy in 1896 banned the football team from playing another athletic club.[21]

Referee and steelworker

Shortly after he left Lehigh, McClung began a career as a college football referee. He began as early as November 1895, when he partnered with Paul Dashiell to officiate a game between Yale and Princeton.[22] The pairing with Dashiell quickly became regular, with McClung acting as referee and Dashiell as Umpire. Former Princeton guard William "Big Bill" Edwards stated that "within my recollection, for many years the two most prominent, as well as most efficient officials, whose names were always coupled, were McClung, Referee, and Dashiell, Umpire. No two better officials ever worked together and there is as much necessity for team work in officiating as there is in playing".[23] Edwards' opinion was often shared by sportswriters and fellow players. After the Yale-Princeton game, a writer for the New York Tribune stated that Dashiell and McClung were "excellent" at their jobs and "that their rulings were just and impartial was admitted everywhere".[24]

In the following year, McClung refereed a single game, again between Yale and Princeton.[25] He was a top candidate for umpiring a contest between Wisconsin and Carlisle in what would be one of the first games played at night, but did not receive the position.[26][27] McClung refereed two games in 1897 alongside Dashiell. The first game they served was Harvard and Yale's rivalry, The Game. The contest, which ended in a 0-0 tie, was the first time the rivalry was played since a bloody 1894 game led it to be cancelled.[28][29] Following that work, they officiated a close game between Cornell and Penn.[30] McClung gained some fame among the football community following the 1897 year, so he was selected to referee in three games the following year. He was chosen before the season to again serve in the Harvard-Yale game, and was likely going to be a referee for the Yale-Princeton contest;[31][32] before the game, however, McClung was replaced by Edgar Wrightington.[33] The other two games refereed that year were for Penn, their contests with Harvard and Cornell.[34][35] McClung's 1899 season was very similar to his previous year. He was selected before the season to referee the Harvard-Yale game,[36] and officiated a game between Pennsylvania and Harvard.[37]

By 1900, McClung and Dashiell's fame had risen considerably. Two western teams, California and Stanford, asked them to officiate their rivalry game. The San Francisco Call, while covering the rivalry, referred to the two as "the two most expert [officials] in America".[38] McClung ended up only refereeing one game that year, his usual role in the Harvard-Yale game.[39] He was sought after for another game for Yale, but had to turn down the offer.[40] He officiated two games in 1901. The first was his usual job at the Yale-Harvard game, which ended up being a very cleanly played contest. The second was another game for Harvard, against Penn.[41][42] McClung's routine was broken in 1902, when he officiated four games. After beginning the year with a normal game between Columbia and Princeton, McClung refereed a game between Columbia and Penn where, for the first time, Dashiell was not umpiring for him.[43][44] The 1903 season saw McClung referee three games, all for Yale. In the season's Yale-Princeton game, he acted as umpire for the first time in his officiating career.[45] As with the previous year, McClung was selected prior to the 1904 season's beginning as the referee for three games for Yale, against Columbia, Princeton, and Harvard.[46] The Princeton game led to a minor controversy surrounding McClung, after he decided to shorten the length of the game.[A 1] He was also chosen by Harvard to officiate their game against Penn,[48] and by Penn in their game with Columbia. In the latter, both teams wanted McClung to umpire; he flatly refused, and decided to shorten the game to 40 minutes.[49]

In 1905, McClung refereed only two games, one of which turned out to be the biggest in his career. The first game of the season was between Harvard and Pennsylvania, which McClung officiated alongside "Big Bill" Edwards. The pairing was troublesome, since both men had previously served almost always as a referee, which left the position of umpire unfilled. Edwards eventually accepted the umpire role, and remained at the position for the rest of his officiating career following the game.[50] The Harvard-Yale game was the most controversial game of McClung's career, although most of the issue surrounded Dashiell's umpiring. Late in the game, the teams were tied 0-0. Yale punted the ball to Francis Burr, Harvard's guard, who called a fair catch. However, Burr was hit by two Yale players and fumbled the ball, which set up Yale's winning score. Harvard fans and players believed that Burr had called the fair catch, while Yale claimed he never had and both officials agreed with Yale. After the game, McClung said that "[the hit] looked ugly, but was within the rules of the game".[51] The officials' decision remained a big problem for college football for some time, and eventually then-president Theodore Roosevelt met with Dashiell to discuss the play. Their reputations as good officials were significantly hurt by the game and Harvard would not allow them to again referee in a game involving their team.[51][52] Following the season's conclusion, McClung joined other prominent football personnel in selecting that year's All-America team. McClung's selection included seven players who were later recognized as consensus All-Americans, and one of which, Tom Shevlin, would later make the Hall of Fame.[53] McClung refereed the final game of his career in 1906, when, alongside William Herbert Corbin, he officiated the Army–Navy Game. Navy, coached by Paul Dashiell, won the contest 10-0.[55]

During the time that he was a referee, McClung also pursued a career in steelmaking. His first work was as a chemist at the Carnegie Steel Company's Carrie Furnace in Rankin, Pennsylvania. During that time, he took up residence in Pittsburgh.[56] Sometime in 1898, McClung was hired as the assistant superintendent at the blast furnaces of the Cambria Steel Company. After serving that position for about five years, he was hired by the Illinois Steel Company and was made the superintendent of the company's Joliet iron and steel blast furnaces. McClung would hold the position until his death, five years later.[57][58]

Death and legacy

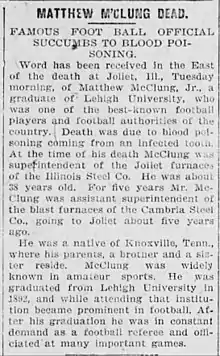

While working at the Joliet Blast Furnaces, McClung developed a severe tooth infection, which eventually gave him blood poisoning. He succumbed to the latter condition on March 3, 1908, at the age of just 39. McClung's death came before those of his parents and all six of his siblings.[57][58] He was replaced just days after his death by W.J. Moore, a chemist who had worked under him at the plant.[59] Following his death, McClung was memorialized by several of his former teammates and officials. When "Big Bill" Edwards wrote and published his book Football Days, he included McClung in his tribute to deceased college football players. He wrote that: "Richard Harding Davis and [McClung] were two Lehigh men whose position in the football world was most prominent. The esteem in which they are held by their Alma Mater is enduring".[60] Edwards also praised McClung and Dashiell's refereeing, stating that "Officials come and go. These men have had their day, but no two ever contributed better work. The game of Football was safe in their hands".[23] Paul Dashiell, when interviewed by Edwards' for Football Days, spoke about his relationship with McClung. He said that:

- One friendship was made in these years that has been worth more than words can tell. I refer to that of Matthew McClung. To be known as a co-official with McClung was a privilege that only those who knew him can appreciate. I had known him before at Lehigh in his undergraduate days, and had played on the same teams with him[...] Never was there a squarer sportsman, or a fairer, more conscientious and efficient official; nor a truer, more gallant type of real man than he. His early death took out of the game a man of the kind we can ill afford to lose and no tribute that I could pay him would be high enough.[61]

Head coaching record

College football

| Year | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Bowl/playoffs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navy Midshipmen (Independent) (1895) | |||||||||

| 1895 | Navy | 5–2 | |||||||

| Navy: | 5–2 | ||||||||

| Total: | 5–2 | ||||||||

College baseball

| Season | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Postseason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lehigh Engineers (Independent) (1895) | |||||||||

| 1895 | Lehigh | 8–12 | |||||||

| Lehigh: | 8–12 | ||||||||

| Total: | 8–12 | ||||||||

See also

College football portal

College football portal Biography portal

Biography portal

References

Notes

- The Yale team showed up to the 1904 contest over forty-five minutes after it was scheduled to begin due to issues with their train. McClung shortened the game's haves to thirty and twenty-five minutes, respectively, instead of their full thirty-five minute duration. Controversy arose among the players, who, among other things, "protested vigorously" against McClung's decision.[47]

Footnotes

- Lehigh Alumni Association (1910), p. 65

- Edwards (1916), p. 348

- McClung (1904), pp. 28-29

- The Lehigh Epitome (1898), pp. 222-223

- The Lehigh Epitome (1890), p. 58

- The Lehigh Epitome (1890), pp. 104, 165

- The Lehigh Epitome (1890), pp. 145, 164-168

- The Lehigh Epitome (1891), pp. 167-171

- The Lehigh Epitome (1895), p. 22

- The Lehigh Epitome (1891), pp. 64, 109, 128

- The Lehigh Epitome (1892), pp. 137, 146

- The Lehigh Epitome (1892), pp. 194-199

- Bealle (1951), p. 44

- Bealle (1951), p. 45

- Navy Game Results 1895-1899

- The Cavalier Daily (1982), p. 7

- Edwards (1916), p. 205

- Jackson (1959), p. 3

- The Salt Lake Herald (1895), p. 2

- Edwards (1916), p. 387

- The New York Tribune (1895), p. 3

- The Norfolk Virginian (1896), p. 1

- The Evening Times (1896), p. 3

- Pruter (2011), pp. 2-3

- Samuels (2011), The Back Page

- The Sun (1897), p. 2

- The Saint Paul Globe (1897), p. 1

- Omaha Daily Bee (1898), p. 10

- Evening Star (1898), p. 7

- Presbrey and Moffat (1901), p. 386

- The Times (1898), p. 8

- The Scranton Tribune (1898), p. 1

- The Kansas City Journal (1899), p. 5

- The Saint Paul Globe (1899), p. 10

- The San Francisco Call (1900), p. 32

- New-York Daily Tribune (1900), p. 5

- The Times (1900), p. 3

- Athletic Association of Harvard Graduates (1901), p. 4

- The San Francisco Call (1901), p. 34

- The Indianapolis Journal (1902), p. 6

- The Saint Paul Globe (1902), p. 8

- The Minneapolis Journal (1903), p. 21

- The Saint Paul Globe (1904), p. 5

- Williams & Norris (1904), p. 127

- The Times-Dispatch (1904), p. 1

- The New-York Tribune (1904), p. 10

- Edwards (1916), p. 391

- Reid (1994), pp. 307-318

- Smith (2011), pp. 46-50

- Whitney (1906), p. 27

- The Minneapolis Journal (1906), p. 3

- Packer (1899), P. 175

- The Allentown Leader (1908), p. 6

- The Iron Trade Review (March 12, 1908), p. 498

- The Iron Trade Review (March 19, 1908), p. 534

- Edwards (1916), pp. 459-460

- Edwards (1916), pp. 389-390

Bibliography

- Books, journals, and yearbooks

- Athletic Association of Harvard Graduates (October 28, 1901). "Football During The Week–Athletic Notes". The Harvard Bulletin. Boston, MA: Harvard Alumni Association. IV (3): 3–4. OCLC 2509751.

- Bealle, Morris Allson (1951). "1895". Gangway for Navy: The Story of Football At United States Naval Academy, 1879-1950. Washington, D.C.: Columbia Publishing Company. OCLC 1667386.

- Cromartie, Bill (1996). Army Navy Football, 1890-1995: The Greatest Rivalry in All of Sports. Atlanta: Gridiron Publishers. ISBN 0-9325-2058-8. OCLC 36118980.

- Edwards, William Hanford (1916). "XX: Umpire and Referee". Football Days: Memories of the Game and of the Men Behind the Ball. New York City: Moffat, Yard and Company. OCLC 2047234.

- Lehigh Alumni Association (1910). Proceedings of the Alumni Association of Lehigh University, June, 1908, to June, 1909, with the Constitution and By-Laws (1909-1910 ed.). Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company. OCLC 62137265.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1890). The Lehigh Epitome '90. XIV. Philadelphia, PA: George F. Lasher Printing. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1891). The Lehigh Epitome '91. XV. Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1892). The Lehigh Epitome '92. XVI. Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1893). The Lehigh Epitome '93. XVII. Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1894). The Lehigh Epitome '94. XVIII. Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1895). The Lehigh Epitome '95. XIX. New Haven, CT: The E.B. Sheldon Company. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- Lehigh University Junior Class (1898). The Lehigh Epitome '98. XXII. New York, NY: The Republic Press. OCLC 9204973. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- McClung, William (1904). "1-1, James McClung". The McClung Genealogy: A Genealogical and Biographical of the McClung Family from the Time of their Emigration to the Year 1904. Pittsburgh, PA: McClung Printing Company. OCLC 5148800.

- Packer, Asa, ed. (1899). Register of The Lehigh University, South Bethlehem, PA (1898-1899 ed.). Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company. OCLC 883846297.

- Presbrey, Frank; James Hugh Moffat, eds. (1901). "Football at Princeton, 1869-1900". Athletics at Princeton: A History. New York City: Frank Presbrey Company. pp. 272–398. OCLC 7641841.

- Pruter, Robert (February 2011). "Indoor Football in Chicago's Coliseum" (PDF). College Football Historical Society. XXIV (II): 1–5. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- Reid, Bill; Ronald A. Smith, ed. (1994). "Daily Season Record From September 13 Through November 25". Big-Time Football at Harvard 1905: The Diary of Coach Bill Reid. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 91–321. ISBN 0-252-02047-2. OCLC 27814901.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Smith, Ronald A. (2011). "Football, Progression Reform, and the Creation of the NCAA". Pay for Play: A History of Big-time College Athletic Reform. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 42–50. ISBN 0-252-09028-4. OCLC 700709008.

- Whitney, Caspar (August 1906). "Other All-America Selections". Spalding's Official Foot Ball Guide. XXIII (275): 23–29. OCLC 3912065. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- Williams, Jesse Lynch; Norris, Edwin M. (November 19, 1904). "Yale 12, Princeton 0". The Princeton Alumni Weekly. The Princeton Publishing Company. V (8): 126–129. ISSN 0149-9270. OCLC 2436114.

- Staff writer (March 12, 1908). "Personals–Death of James Meehan". The Iron Trade Review. Cleveland. XLII (11): 498. OCLC 6923459.

- Staff writer (March 19, 1908). "Personals and Obituary". The Iron Trade Review. Cleveland. XLII (12): 534. OCLC 6923459.

- Newspapers

- Jackson, Elmer M. (September 26, 1959). "Out of the Past: St. John's Was Navy's Opener Back in 1885". The Evening Capital. Annapolis, MD. p. 3. OCLC 9259920.

- Nesbit, Joanne (September 11, 2000). "Roosevelt May be 'Father of Annual Army-Navy Football Game'". The University Record. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

- Samuels, Robert S. (November 18, 2011). "A History of Harvard-Yale". The Harvard Crimson. Cambridge, MA. The Back Page. ISSN 1932-4219. OCLC 6324327. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- University Guides (February 23, 1982). "Fire on the Lawn, 1895: Rotunda up in Smoke". The Cavalier Daily. Charlottesville, VA. p. 7. OCLC 22283127.

- Staff writer (March 5, 1908). "Matthew M'Clung Dead: Famous Foot Ball Official Succumbs to Blood Poisoning". The Allentown Leader. Allentown, PA. p. 6. OCLC 18987721.

- Staff writer (October 7, 1895). "Notice to Subscribers". The Cornell Daily Sun. XVI (10). Ithaca, NY. p. 1. ISSN 1095-8169. OCLC 232117810. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 12, 1898). "Dashiell to Umpire the Big Matches". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. p. 7. ISSN 2331-9968. OCLC 2260929. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Staff writer (December 19, 1896). "Football Innovation–Game Will Be Played at Night for First Time". The Evening Times. Washington, D.C. p. 3. ISSN 1941-0689. OCLC 10954477. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 26, 1902). "Hard Game For Princeton: Yet the Tigers Rolled Up a Score of 21 Against Columbia". The Indianapolis Journal. Indianapolis. p. 6. ISSN 2332-0982. OCLC 192107329. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Staff writer (September 28, 1899). "Wichita's Great Race–Puffs From the Pipe". The Kansas City Journal. Kansas City, MO. p. 5. ISSN 2157-3492. OCLC 13484189. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 30, 1903). "East Versus West: Have The 'Big Nine' Football Teams Advanced Beyond 'Big Six' In Science?". The Minneapolis Journal. Minneapolis, MN. p. 8. ISSN 2151-3953. OCLC 1757631. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Staff writer (December 1, 1906). "Army And Navy In Battle Today: Soldiers and Sailors Meet in Annual Game at Philadelphia Today". The Minneapolis Journal. Minneapolis, MN. p. 3. ISSN 2151-3953. OCLC 1757631. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 25, 1895). "On Everyone's Tongue: The Football Game And Not The Weather". New-York Daily Tribune. New York City. p. 3. ISSN 1941-0646. OCLC 9405688. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 24, 1900). "Harvard-Yale To-Day: Greatest Football Battle Of The Year To Be Fought At New-Haven". New-York Daily Tribune. New York City. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. OCLC 9405688. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 23, 1904). "Penn Beats Columbia: New-Yorkers Lose Through Poor Headwork–Metzenthin's Pluck". New-York Daily Tribune. New York City. p. 10. ISSN 1941-0646. OCLC 9405688. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 22, 1896). "The Blue Goes Down–Before the Irresistible Onslaught of the Mighty Sons of Historic Old Nassau". The Norfolk Virginian. Norfolk, VA. p. 1. ISSN 2166-577X. OCLC 11886168. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 16, 1898). "Gossip From The Gridiron: Possibility of a Real Championship Contest Again Looms Up in a Collegiate Sky". Omaha Daily Bee. Omaha, NE. p. 10. ISSN 2169-7264. OCLC 42958170. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 26, 1897). "Year's Finest Game On Franklin Field: Pennsylvania Held to a Single Touchdown by the Cornell Eleven". The Saint Paul Globe. St. Paul, MN. p. 1. ISSN 2151-5328. OCLC 21579130. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 5, 1899). "Harvard Won Easy: Defeated The Pennsylvanians, And Did Not Permit Them To Score". The Saint Paul Globe. St. Paul, MN. p. 10. ISSN 2151-5328. OCLC 21579130. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 2, 1902). "Penn Blanks Columbia: Red and Blue Team's Play Surprises the Spectators". The Saint Paul Globe. St. Paul, MN. p. 8. ISSN 2151-5328. OCLC 21579130. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 13, 1904). "Football Team Is Making Big Strides–Football Officials Chosen". The Saint Paul Globe. St. Paul, MN. p. 5. ISSN 2151-5328. OCLC 21579130. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 23, 1895). "Long Hair and Pigskin–Yale and Princeton". The Salt Lake Daily Herald. Salt Lake City, UT. p. 2. ISSN 1941-3033. OCLC 11987624. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 25, 1900). "Referee, But No Umpire, Selected For The Thanksgiving Day Game". San Francisco Call. San Francisco, CA. p. 32. ISSN 1941-0719. OCLC 13146227. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 24, 1901). "Overwhelming Defeat For Yale Is Administered By Harvard". San Francisco Call. San Francisco, CA. p. 34. ISSN 1941-0719. OCLC 13146227. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 25, 1898). "Victory For Keystone Kickers: Cornell is Defeated by a Score of 12-6". The Scranton Tribune. Scranton, PA. p. 1. ISSN 2151-4038. OCLC 10437632. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 14, 1897). "Yale And Harvard Tie: Stirring Football Struggle Between Old Rivals". The Sun. New York City. pp. 1–2. OCLC 477686775. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 5, 1898). "A Big Crowd Expected: Great Interest in the Harvard-Pennsylvania Game Today". The Times. Washington, D.C. p. 8. OCLC 9285626. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Staff writer (November 8, 1900). "The Yale-Carlisle Game: Elaborate Preparations Being Made for the Contest". The Times. Washington, D.C. p. 3. OCLC 9285626. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Staff writer (October 30, 1904). "The Tide Is Now Turned: Pennsylvania Prevents Harvard From Scoring At Cambridge". The Times-Dispatch. Richmond, VA. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0700. OCLC 12872288. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Other

- Staff (2013). "Navy Yearly Results–1895-1899". College Football Data Warehouse. 1895: 5-2-0. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Staff (2014). "1906 Navy Midshipmen Schedule and Results". College Football at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved October 29, 2014.