Cushitic peoples

The Cushitic peoples (or Cushites) are a grouping of people who are primarily indigenous to Northeast Africa (Nile Valley and Horn of Africa) and speak or have historically spoken Cushitic languages of the Afroasiatic language family. Cushitic languages are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia), as well as the Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), and parts of the African Great Lakes region (Tanzania and Kenya).[8] Some examples of these peoples include the Cushitic speaking ethnic groups (Oromo, Somali, Beja, Agaw, Afar, Saho and Sidamo).[9]

Areas where Modern Cushitic languages are currently prevalent (Cushitic People subgroups that no longer speak Cushitic languages are not represented in this map). | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| The Horn of Africa, Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), parts of the African Great Lakes region, and due to immigration in parts of the Arabian Peninsula, Israel, and the Western world. | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly various Cushitic languages (Oromo and Somali being the largest), some Arabic (liturgical, co-official, or language shifts) Modern Hebrew & European languages (immigration), and Nilo-Saharan languages (e.g. Nubian due to language shifts) | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Islam (Sunni), Christianity (Oriental Orthodoxy-Orthodox Tewahedo: Orthodox Christianity and Eritrean Orthodoxy · P'ent'ay: Ethiopian-Eritrean Evangelicalism · Catholicism: Eritrean Catholicism and Ethiopian Catholicism) Minority: Syncretism, Judaism (Beta Israel) Traditional Old Cushitic religion(s): (Waaqism/Waaqeffanna) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Afro-Asiatic peoples[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

Linguistic evidence indicates that Cushitic languages were spoken in Lower Nubia, an ancient region which straddles present day Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan, before the arrival of North Eastern Sudanic languages from Upper Nubia.[10] Many extinct populations of northern Nubia such as the Medjay and the Blemmyes spoke Cushitic languages related to the modern Beja language.[11] Less certain are hypotheses which propose that Cushitic languages were spoken by the people of the C-Group culture in northern Nubia,[10] or the people of the Kerma culture in southern Nubia (other, more recent, research suggests a Nilo-Saharan linguistic affinity for the Kerma culture [12][13][14]). Historical linguistic analysis indicates that the languages spoken in the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture of the Rift Valley and surrounding areas, may have been languages of the South Cushitic branch.[15]

Cushitic populations constitute the majority of the population in the Horn of Africa; an area that is believed to be the location of dispersal of Cushitic speakers across most of East Africa. The Cushitic peoples primarily adhere to Islam (Pew: 68% to 77% Sunni[16]) and Orthodox Christianity with a small minority still practicing traditional beliefs and Judaism. The Somali language is the sole Cushitic language recognized as an official language while Oromo and Afar are recognized as a regional working languages in Ethiopia.

Ethnonym

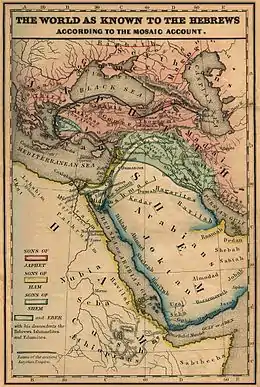

The word Cushi or Kushi (Hebrew: כּוּשִׁי kuši) appears several times in the Hebrew Bible to refer to a dark-skinned person of Northeast African descent, equivalent to Greek Aethiops. The word has later been changed to "Ethiopia/Ethiopian" in non-Hebrew versions of the Bible to match the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Cushi is a derivation of Cush (כּוּשׁ Kūš), referring to the ancient Kingdom of Kush. In the Hebrew Bible, Cushites are considered descendants of Noah's grandson, Cush the son of Ham. In biblical and historical usage this continued, the term "Cushites" (Ethiopid race) referring to individuals of East African origin (Horn of Africa and Sudan).[17][18] The Cushitic-speaking peoples today comprise the Agaw, Oromo, Somali, Afar, and several other tribes, and were considered offspring of Cush in Masudi's Meadows of Gold from 947 AD.[19] The Beja people, who also speak a Cushitic language, have specific genealogical traditions of descent from Cush.[20][21]

The term Cushite then derives from the ancient peoples of northeastern Africa, whose heritage can be traced most clearly in the languages descended from those of the ancient peoples who inhabited the corridor between present day Southern Egypt and Tanzania.[22] In broad terms the peoples now designated as Cushite are the cultural descendants of those peoples. The term Cushite today is an ethnolinguistic designation, languages have a much more stable and traceable identity and heritage than cultural groups. The Cushite peoples are thus those who speak languages or have historically spoken languages of the Cushite cluster in the Afro-Asiatic language family. These cultural groups may be of diverse types and exhibit a variety of unique features but with powerful common cultural, ethnic and linguistic traits, including nomadic cattle pastoralist traditions.

History

Origin

The exact ethnogenesis of Cushitic peoples is still being researched, however, many Cushitic populations are E1b1b and can also be paternally traced back to having ethnic origins in the Nile Valley through haplogroup E-M78 and the Red Sea region of the Horn of Africa through haplogroup E-V1515.[25][26][27][28][29]

Archeological evidence and linguistic evidence gathered from toponyms and ancient Egyptian records suggest that the earliest evidence of Cushitic speech is not found where the language family is most predominant today—namely the Horn of Africa, but in a region of Sudan. Some prehistoric northern Nubian cultures such as the A-Group Culture and C-Group Culture have been regularly linked to early Cushitic populations. Other linguists consider the Horn of Africa to be the original homeland of the proto-Afroasiatic language as it is considered the region the Afroasiatic language family displays the greatest diversity, a sign often viewed to represent a geographic origin.[5][30][31][32] Ancient DNA offers a new source of information about eastern African Holocene prehistory, and an important next direction is to integrate this information rigorously with insights provided by the longer-established disciplines of archaeology and linguistics.[33]

Cushitic populations most likely formed and started migrating out of the Nile Valley in prehistory. Laas Geel, ancient cave paintings in Northern Somalia attest to the first signs of a population believed to be ancestral to the Afro-Asiatic speakers in the Horn of Africa. In an excellent state of preservation, the rock art depicts wild animals and decorated cattle (cows and bulls). They also feature herders, possibly pastoral nomads, who are the creators of the paintings.[34] By the 5th millennium BC, the people who inhabited prehistoric Sudan participated in the Neolithic revolution, the domestication of animals usually numbered among the “Neolithic package” brought on by the advent of agriculture. Nubian rock reliefs depict scenes that seem to be suggestive of the same cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Northeast Africa and the Nile Valley.[35] Domestic sheep, goats, and cattle of southwest Asian origin were first introduced to northeastern Africa in Sudan around ≈8000 years before present (BP), and spread into eastern Africa beginning ≈5000 BP, ultimately reaching southernmost Africa by ≈2000 BP. How pastoralism—a way of life centered on herding animals—spread into eastern Africa is unclear. Livestock appear in northern Ethiopia and Djibouti relatively late, ≈4500–4000 BP, and are poorly documented elsewhere in the Horn of Africa and in South Sudan.

By the 5th millennium BC, Proto-Cushites who inhabited what is now Sudan likely participated in the Neolithic revolution which allowed for the domestication of animals by sedentary groups who were previously cultivators.[36] Donkeys were probably first domesticated by pastoral people in Nubia the ancestors of the modern donkey being the Nubian and Somali subspecies of African wild ass.[37] Donkeys supplanted the ox as the chief pack animal of that culture and its domestication served to increase the mobility of pastoral cultures, having the advantage over ruminants of not needing time to chew their cud, and were vital in the development of long-distance migrations across Africa.[38] Nubian rock reliefs depict scenes that seem to be suggestive of the same cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Northeast Africa and the Nile Valley.[35] Puntland and the Somaliland regions of Somalia is home to numerous such archaeological sites and megalithic structures, with similar rock art found at Haadh, Gudmo Biyo Cas, Dhambalin, Dhagah Maroodi and numerous other sites, while ancient edifices are, among others, found at Awbare, Awbube, Amud, Abasa, Sheikh, Aynabo, Aw-Barkhadle, Heis, Maydh, Haylan, Qa’ableh, Qombo'ul and El Ayo.[39] However, many of these old structures have yet to be properly explored, a process which would help shed further light on local history and facilitate their preservation for posterity.[40]

East Africa

Archeological and linguistic evidence suggests that Cushitic speakers dominated significant areas of East Africa before the Bantu expansion in 1,000 BC to 1 AD. With the maturation of multivariate skeletal analysis two ancestral groups were identified "Mediterranean Caucasoid" affinities present in the region were associated with ancestral Cushitic populations specifically, while the "Negroid" remains belonged to early Nilotic groups.[41]

In the influential book The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History published in 1982, Ehret broadly agreed with Harold C. Fleming earlier hypothesis on the persistence of ancestral ethnoracial boundaries in Africa despite later periods of contact. However, he still eschewed the earlier so-called Hamites terminology in favor of other nomenclature.

Recent genetic analysis of the ancient remains of Elmenteitan has proven that the population of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic were also responsible for the pastoralist Elmenteitan culture that lived in the Rift Valley during the same period.[42]

This population is thought to have been responsible for the stone monoliths, walled enclosures, irrigation systems and other related prehistoric cultural remains found in East Africa. Recent evidence suggests that the two populations were not as insular as once thought with modern groups such as the Maasai and the Turkana peoples exhibiting both genetic and cultural influence from both these prehistoric groups.[43] According to archaeological dating of associated artifacts and skeletal material, the Cushites first settled in the lowlands of Kenya between 5,200 and 3,300 ybp, a phase referred to as the Lowland Savanna Pastoral Neolithic. These herding communities subsequently spread to the highlands of Kenya and Tanzania around 3,300 ybp, which is consequently known as the Highland Savanna Pastoral Neolithic phase.[44][45] The Kalokol Pillar Site is an archaeological site on the western side of Lake Turkana in Kenya. Pillar sites, or namoratunga, such as this one are characterized by columnar basalt pillars, and several of these sites are known to be cemeteries dating to the Pastoral Neolithic c. 5000-4000 BP.[46] Archaeologists have previously argued that pillars at some of these sites are aligned with stars of known calendrical importance to current Cushitic-speaking communities such as the Borana in northern Kenya.[47] The archaeological sites were thought to have served archaeoastronomical purposes, but new radiocarbon dating efforts have called into question these interpretations, given that the sites are now known to be older than previously assumed.[48]

The southernmost groups of Savanna Pastoral Neolithic herders may have been responsible for the eventual spread of pastoralism to southern Africa: genetic data show a link between a Savanna Pastoral Neolithic individual from Luxmanda, Tanzania, and ancient herders in the western Cape, South Africa.[49]

Azania is a name that has been applied to various parts of southeastern tropical Africa.[50] In the Roman period and perhaps earlier, the toponym referred to a portion of the Southeast Africa coast extending from Kenya,[51] to perhaps as far south as Tanzania. Historians have previously connected Pastoral Neolithic communities with "Azanians" mentioned in historical texts.[52]

The Horn of Africa

Shell middens 125,000 years old have been found in Eritrea,[53] indicating the diet of early humans included seafood obtained by beachcombing.

According to linguists, the Horn of Africa could possibly be the original homeland of the proto-Afroasiatic language as it is considered the region the Afroasiatic language family displays the greatest diversity, a sign often viewed to represent a geographic origin. The Horn of Africa is also the place where the haplogroup E1b1b originated from, Christopher Ehret and Shomarka Keita have suggested that the geography of the E1b1b lineage coincides with the distribution of the Afroasiatic languages.[5] Genetic analysis done on the Afroasiatic speaking population further found that a pre-agricultural back-to-Africa migration into the Horn of Africa occurred through Egypt 23,000 years ago and it brought a non-African ancestry dubbed Ethio-Somali in the region.[54]

The earliest evidence of state-building in the Horn of Africa comes from an area recorded in ancient Egyptian sources. The Land of Punt (Egyptian: pwnt; alternate Egyptological readings Pwene(t)[55]) was an ancient kingdom. A trading partner of Egypt, it was known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory, and wild animals. The region is known from ancient Egyptian records of trade expeditions to it.[55] The earliest recorded ancient Egyptian expedition to Punt was organized by Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty (25th century BC). However, gold from Punt is recorded as having been in Egypt as early as the time of Pharaoh Khufu of the Fourth Dynasty.[56]

Subsequently, there were more expeditions to Punt in the Sixth, Eleventh, Twelfth and Eighteenth dynasties of Egypt. In the Twelfth Dynasty, trade with Punt was celebrated in popular literature in the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor.

It is possible that it corresponds to Opone as later known by the ancient Greeks,[57][58][59] while some biblical scholars have identified it with the biblical land of Put.[60] The kingdom was famed for its incense as shown by inscriptions on the tomb of Hatshepsut

Said by Amen, the Lord of the Thrones of the Two Land: 'Come, come in peace my daughter, the graceful, who art in my heart, King Maatkare [ie. Hatshepsut]...I will give thee Punt, the whole of it...I will lead your soldiers by land and by water, on mysterious shores, which join the harbours of incense...They will take incense as much as they like. They will load their ships to the satisfaction of their hearts with trees of green [i.e., fresh] incense, and all the good things of the land.'[61]

At times Punt is referred to as Ta netjer (tꜣ nṯr), the "Land of the God".[62] The exact location of Punt is still debated by historians. Most scholars today believe Punt was situated to the southeast of Egypt, most likely in the coastal region of modern Djibouti, Somalia, northeast Ethiopia, Eritrea, and the Red Sea littoral of Sudan.[63] It is also possible that the territory covered both the Horn of Africa and Southern Arabia.[64][65] Puntland, the Somali administrative region situated at the extremity of the Horn of Africa, is named in reference to the Land of Punt.[66] Interestingly the term Habesha (also known as 'Abyssinian people') was used historically (before Abyssinian Ethiopian adaption) to refer to all the populations in the Horn of Africa by Arab travelers and geographers. The first among these travelers was Al-Ya'qubi, who visited the region in 872 CE. The word is thought by some scholars to be of Egyptian origin, South Arabian expert Eduard Glaser, claimed that the hieroglyphic ḫbstjw, used in reference to "a foreign people from the incense-producing regions" (i.e. Punt) used by Queen Hatshepsut c. 1460 BC, was the first usage of the term or somehow connected. Much of the worlds frankincense, around 82%, is still produced in Somalia, with some frankincense also gathered in adjacent Southern Arabia, Ethiopia and Sudan.[67][68][69]

Ta netjer (tꜣ nṯr), meaning "God's Land".[70] This referred to the fact that it was among the regions of the Sun God, that is, the regions located in the direction of the sunrise, to the East of Egypt. These eastern regions' resources included products used in temples, notably incense. Older literature (and current non-mainstream literature) maintained that the label "God's Land", when interpreted as "Holy Land" or "Land of the gods/ancestors", meant that the ancient Egyptians viewed the Land of Punt as their ancestral homeland. W. M. Flinders Petrie believed that the Dynastic Race came from or through Punt and that "Pan, or Punt, was a district at the south end of the Red Sea, which probably embraced both the African and Arabian shores."[71] Moreover, E. A. Wallis Budge stated that "Egyptian tradition of the Dynastic Period held that the aboriginal home of the Egyptians was Punt...".[72] However, the term Ta netjer was not only applied to Punt, located southeast of Egypt, but also to regions of Asia east and northeast of Egypt, such as Lebanon, which was the source of wood for temples.[73]

While the Egyptians "were not particularly well versed in the hazards of sea travel, and the long voyage to Punt, must have seemed something akin to a journey to the moon for present-day explorers...the rewards of [obtaining frankincense, ebony and myrrh] clearly outweighed the risks."[74][75] Hatshepsut's 18th dynasty successors, such as Thutmose III and Amenhotep III also continued the Egyptian tradition of trading with Punt.[76] The trade with Punt continued into the start of the 20th dynasty before terminating prior to the end of Egypt's New Kingdom.[76] Papyrus Harris I, a contemporary Egyptian document that detailed events that occurred in the reign of the early 20th dynasty king Ramesses III, includes an explicit description of an Egyptian expedition's return from Punt, an ill-defined region in the Horn of Africa:

They arrived safely at the desert-country of Coptos: they moored in peace, carrying the goods they had brought. They [the goods] were loaded, in travelling overland, upon asses and upon men, being reloaded into vessels at the harbour of Coptos. They [the goods and the Puntites] were sent forward downstream, arriving in festivity, bringing tribute into the royal presence.[77]

After the end of the New Kingdom period, Punt became lost "an unreal and fabulous land of myths and legends."[78] However, Egyptians continued to compose love songs about Punt, "When I hold my love close, and her arms steal around me, I'm like a man translated to Punt, or like someone out in the reedflats, when the world suddenly bursts into flower." [79]

At some point after the fall of Punt or possibly running concurrently begins evidence of a Semitic-speaking presence in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia as early as 2000 BC.[80][81]

Dʿmt (South Arabian alphabet : ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ; Unvocalized Ge'ez : ደዐመተ, DʿMT theoretically vocalized as ዳዓማት, Daʿamat[82] or ዳዕማት, Daʿəmat[83]) was a kingdom located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia (Tigray Region) that existed during the 10th to 5th centuries BC. Few inscriptions by or about this kingdom survive and very little archaeological work has taken place. As a result, it is not known whether Dʿmt ended as a civilization before the Kingdom of Aksum's early stages, evolved into the Aksumite state, or was one of the smaller states united in the Kingdom of Aksum possibly around the beginning of the 1st century.[84] Some sources consider the Sabaean influence on this ancient state to be minor, limited to a few localities, and disappeared after a few decades or a century, perhaps representing a trading or military colony in some sort of symbiosis or military alliance with the civilization of Dʿmt or some other proto-Aksumite state.[85][86] However other sources hold that D'mt, though having indigenous roots, was under strong South Arabian economic and cultural influence.[87] Other scholars however consider this period the beginning of an ancient Southwestern migration of Semitic-speaking peoples that then assimilated native Cushitic speakers.[88]

; Unvocalized Ge'ez : ደዐመተ, DʿMT theoretically vocalized as ዳዓማት, Daʿamat[82] or ዳዕማት, Daʿəmat[83]) was a kingdom located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia (Tigray Region) that existed during the 10th to 5th centuries BC. Few inscriptions by or about this kingdom survive and very little archaeological work has taken place. As a result, it is not known whether Dʿmt ended as a civilization before the Kingdom of Aksum's early stages, evolved into the Aksumite state, or was one of the smaller states united in the Kingdom of Aksum possibly around the beginning of the 1st century.[84] Some sources consider the Sabaean influence on this ancient state to be minor, limited to a few localities, and disappeared after a few decades or a century, perhaps representing a trading or military colony in some sort of symbiosis or military alliance with the civilization of Dʿmt or some other proto-Aksumite state.[85][86] However other sources hold that D'mt, though having indigenous roots, was under strong South Arabian economic and cultural influence.[87] Other scholars however consider this period the beginning of an ancient Southwestern migration of Semitic-speaking peoples that then assimilated native Cushitic speakers.[88]

In the classical era, the Macrobians who were a legendary people and kingdom positioned in the Horn of Africa were mentioned by Herodotus. They were reputed for their longevity and wealth, and were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".[89] The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor Cambyses II, upon his conquest of Egypt (525 BC), sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based on his stature and beauty, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to draw it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.[89][90] The Macrobians were a regional power that were known from east to west and were highly advanced in architecture and extremely known for their wealth were they were noted for its gold, which was so plentiful that the Macrobians shackled their prisoners in golden chains. According to Herodotus, the Macrobians practiced an elaborate form of embalming. The Macrobians preserved the bodies of the dead by first extracting moisture from the corpses, then overlaying the bodies with a type of plaster, and finally decorating the exterior in vivid colors in order to imitate the deceased as realistically as possible. They then placed the body in a hollow crystal pillar, which they kept in their homes for a period of about a year.[91]

After the introduction of Christianity, Judaism and Islam the respective histories of the Cushitic populations diverged, forming various city-states, empires and sultanates.[92]

Sudan

Nubia or Ta-Seti was an ancient region in northeastern Africa, extending approximately from the Nile Valley (near the first cataract in Upper Egypt) eastward to the shores of the Red Sea, southward to near Khartoum (in what is now Sudan), and westward to the Libyan Desert. Nubia is academically traditionally divided into two regions, the southern portion, which extended north to the southern end of the second cataract of the Nile was known as Upper Nubia; this was called Kush (Cush) under the 18th-dynasty pharaohs of ancient Egypt and was called Aethiopia by the ancient Greeks. Lower Nubia was the northern part of the region, located between the second and the first cataract of Aswān; this was called Wawat.

Lower Nubia is the northernmost part of Nubia, downstream on the Nile from Upper Nubia. Sometimes, it overlapped Upper Egypt stretching to the First and Second Cataracts (the region known to Greco-Roman geographers as Triakontaschoinos), so roughly until Aswan. A great deal of Upper Egypt and northern Lower Nubia were flooded with the construction of the Aswan High Dam and the creation of Lake Nasser. However the intensive archaeological work conducted prior to the flooding means that the history of the area is much better known than that of Upper Nubia. Its history is also known from its long relations with Egypt.

In Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia there was present a series of cultures, the Badarian, Amratian, Gerzean, A-Group, B-Group, and C-Group.

Linguistic evidence (according to Claude Rilly 2008, 2010, 2016 and Julien Copper 2017) indicates that in antiquity, peoples speaking Cushitic languages inhabited Lower Nubia, a region between present day Southern Egypt and Northernmost Sudan (including ancient peoples such as the C-Group culture, the Blemmyes, and the Medjay), and that peoples speaking Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudanic branch inhabited Upper Nubia to the south (such as the people of the ancient Kerma culture), before the spread of Eastern Sudanic languages further north into Lower Nubia.[93][94][95][96]

Lower Nubia was occupied by Egypt, when the Egyptians withdrew during the First Intermediate Period Lower Nubia seems to have become part of the Upper Nubian Kingdom of Kerma. The New Kingdom occupied all of Nubia and Lower Nubia was especially closely integrated into Egypt, but with the Second Intermediate Period it became the centre of the independent state of Kush based around Napata. Perhaps around 591 BC the capital of Kush was transferred south to Meroe. It is also uncertain to which language family the ancient Meroitic language is related. Kirsty Rowan suggests that Meroitic, like the Egyptian language, belongs to the Afroasiatic family.[97][98] Claude Rilly on theater hand, proposes that Meroitic, like the Nobiin (or Nubian) language, belongs to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan family.[99][100]

With the fall of the Meroitic Empire in the fourth century AD by the Nobatae [101] and the Axumites the area became home to X-Group, also known as the Ballana culture who were likely the Nobatae introducing the Nobiin languages to Nubia. This evolved into the Christian state of Nobatia by the fifth century. Nobatia was merged with the Upper Nubian state of Makuria, but Lower Nubia became steadily more Arabized and Islamicized and eventually became de facto independent as the state of al-Maris. Most of Lower Nubia was formally annexed by Egypt during the Ottoman conquest of 1517, and it has remained a part of Egypt since then, with only the far south being in Sudan.

Genetic evidence (a study by Dobon et al. 2015) suggests modern Nubians do not cluster with groups of the same linguistic affiliation, but with Sudanese Afro-Asiatic speaking groups (Sudanese Arabs and Cushitic Beja) and Afro-Asiatic Ethiopians. Nubians were reported to be more similar to Egyptians and Ethiopians in their Mitochondrial and Y-DNA lineages but close to Ethiopians in their overall genetic affinities. Also according to the study, "Nubians were influenced by Arabs as a direct result of the penetration of large numbers of Arabs into the Nile Valley over long periods of time following the arrival of Islam around 651 A.D".[102]

Other studies have linked the ancient population of Sudan and parts of Egypt to the Horn of Africa, though this is not entirely conclusive and must be placed in the context of hypotheses informed by archaeological, linguistic, geographic and other data. In such contexts, the physical anthropological evidence indicates that early Nile Valley populations can be identified as part of an African lineage, but exhibiting local variation. This variation represents the short- and long-term effects of evolutionary forces, such as gene flow, genetic drift, and natural selection, influenced by culture and geography.[103][104][105][106][107]

The Blemmyes were a Beja tribal kingdom that existed from at least 600 BC to the 3rd century AD in Nubia. They were described in Roman histories of the later empire, with the Emperor Diocletian enlisting Nobatae mercenaries from the Western Desert oases to safeguard Aswan, the empire's southern frontier, from raids by the Blemmyes.[108][109] The Blemmyes occupied a considerable region in what is modern day Sudan. There were several important cities such as Faras, Kalabsha, Ballana and Aniba. All were fortified with walls and towers of a mixture of Egyptian, Hellenic, Roman and Nubian elements. Blemmyes culture was also under the influence of the Meroitic culture. Their religion was centered in the temples of Kalabsha and Philae. The former edifice was a huge local architectural masterpiece, where a solar, lion-like divinity named Mandulis was worshipped. Philae was a place of mass pilgrimage, with temples for Isis, Mandulis, and Anhur. It was where the Roman Emperors Augustus and Trajan made many contributions with new temples, plazas, and monumental works.

South Africa

Ancient South Cushitic speaking pastoralists hailing from East Africa migrated across Southeastern Africa and their presence is today marked by genetic evidence of their ancestry present in the modern ancestries of all sampled San and Khoe, who are affected by the agro-pastoralist migrations millennia ago.[110] The migration of these peoples introduced pastoralism to Eastern and Southern Africa during Savannah Pastoral Neolithic. The skin pigmentation gene, SLC24A5, experienced recent adaptive evolution in the Khoisan populations of far southern Africa, haplotype analysis and demographic models indicate that the allele was introduced into the Khoe-San only within the past 3,000 years by eastern African pastoralists. The strong selection of SLC24A5 is a rare example of strong, ongoing adaptation in very recent human history.[111][112]

Languages

Cushitic Languages

The Cushitic languages are usually considered to include the following branches:

- North Cushitic (Beja)

- Central Cushitic (Agaw languages)

- East Cushitic

- South Cushitic

The Somali language is the sole Cushitic language recognized as an official language while Oromo is recognized as a regional working language in Ethiopia. Afar and Somali are recognized as national languages but are not official languages in Djibouti.

Extinct Cushitic languages

Linguistic evidence (according to Claude Rilly 2008, 2010, 2016 and Julien Copper 2017) indicates that in antiquity, Cushitic languages were spoken in Lower Nubia, an ancient region which straddles present day Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan, and that Nilo-Saharan languages of the Eastern Sudanic branch were spoken in Upper Nubia to the south (where the ancient Kerma culture was located), before the spread of Eastern Sudanic languages further north into Lower Nubia.[93][94][95][96]

Julien Cooper (2017) states that in antiquity, Cushitic languages were spoken in Lower Nubia (the northernmost part of modern-day Sudan):

"In antiquity, Afroasiatic languages in Sudan belonged chiefly to the phylum known as Cushitic, spoken on the eastern seaboard of Africa and from Sudan to Kenya, including the Ethiopian Highlands."[114]

Julien Cooper (2017) also states that Eastern Sudanic speaking populations from southern and west Nubia gradually replaced the earlier Cushitic speaking populations of this region:

"In Lower Nubia there was an Afroasiatic language, likely a branch of Cushitic. By the end of the first millennium CE this region had been encroached upon and replaced by Eastern Sudanic speakers arriving from the south and west, to be identified first with Meroitic and later migrations attributable to Nubian speakers."[115]

In Handbook of Ancient Nubia, Claude Rilly (2019) states that Cushitic languages once dominated Lower Nubia along with the Ancient Egyptian language. Rilly (2019) states:

"Two Afro-Asiatic languages were present in antiquity in Nubia, namely Ancient Egyptian and Cushitic."[116]

Rilly (2019) mentions historical records of a powerful Cushitic speaking race which controlled Lower Nubia and some cities in Upper Egypt. Rilly (2019) states:

"The Blemmyes are another Cushitic speaking tribe, or more likely a subdivision of the Medjay/Beja people, which is attested in Napatan and Egyptian texts from the 6th century BC on."[117]

On page 134:

"From the end of the 4th century until the 6th century AD, they held parts of Lower Nubia and some cities of Upper Egypt."[118]

He mentions the linguistic relationship between the modern Beja language and the ancient Cushitic Blemmyan language which dominated Lower Nubia and that the Blemmyes can be regarded as a particular tribe of the Medjay:

"The Blemmyan language is so close to modern Beja that it is probably nothing else than an early dialect of the same language. In this case, the Blemmyes can be regarded as a particular tribe of the Medjay."[119]

Ethiosemitic Languages

- North Ethiopic

- Ge’ez

- Tigre

- Tigrinya

- Dahalik

- South Ethiopic

- Transversal South Ethiopic

- Amharic – working language of the Federal Government of Ethiopia.

- Harari–East Gurage

- Outer South Ethiopic

- Transversal South Ethiopic

The historical linguistics of the relationship between Ethiosemitic languages and Cushitic languages is multi-layered and complex, not yet fully understood. Amharic, Argobba and Tigrinya seem to have a Central Cushitic substratum; Tigre contains a North Cushitic[120] substratum while Harari-Gurage languages reveal Highland East Cushitic influences.[121] The Agaw are mentioned in an inscription of the fourth century emperor Ezana of Axum having conquered their lands.[122] Based on this evidence, a number of experts embrace a theory first stated by European scholars Edward Ullendorff and Carlo Conti Rossini that they are the original inhabitants of much of the northern Ethiopian Highlands, and were either forced out of their original settlements or assimilated by Semitic-speaking Tigrayans and Amharas.[123] This theory is further strengthened by the existence of a Cushitic substratum in Ethiopian Semitic languages indicating population assimilation of an ancient migration from Southwest Arabia.[124][125][126] Ethiopian scholars specializing in Ethiopian Studies such as Messay Kebede and Daniel E. Alemu generally disagree with this theory arguing that the migration was one of reciprocal exchange, if it even occurred at all.

Kebede states the following:

"This is not to say that events associated with conquest, conflict and resistance did not occur. No doubt, they must have been frequent. But the crucial difference lies in the propensity to present them, not as the process by which an alien majority imposed its rule but as part of an ongoing struggle of native forces competing for supremacy in the region. The elimination of the alien ruler indigenize Ethiopian history in terms of local actors."[125][126]

Central Semitic languages (liturgical and/or cultural shift)

Nilo-Saharan languages (language shift or substantial Cushitic ancestry)

- Nubian (related to Northern Cushites)

- Samburu (related to the Rendille)

- Datooga (related to the Iraqw)

As it relates to Nubians, although Cushitic is believed to be numbered among the earlier languages spoken in parts of Nubia, the classification of the Meroitic language of later periods is uncertain due to the scarcity of data and difficulty in interpreting it. Since the alphabet was deciphered in 1909, it has been proposed that Meroitic is related to the Nubian languages and similar languages of the Nilo-Saharan phylum.[127][128] The competing claim is that Meroitic is a member of the Afroasiatic phylum.[129]

Ethnic groups

The Oromo are an ethnic group inhabiting Ethiopia. They are one of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia and represent 34.4% of Ethiopia's population.[130] Oromos speak the Oromo language as a mother tongue (also called Afaan Oromoo and Oromiffa), which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. The word Oromo is sometimes mistakenly said to have appeared in European literature for the first time in 1893. However, it was used as early as in 1868 by Arnaud d'Abbadie Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie who explained that the people that the Amhara speaking Ethiopians called Galla actually call themselves Oromo.

The Somalis are an ethnic group inhabiting the Horn of Africa.[131] The overwhelming majority of Somalis speak the Somali language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family. They are predominantly Muslim, mostly Sunni or non-denominational Muslim. Ethnic Somalis number around 12–18 million and are principally concentrated in Somalia (around 9 million),[132] Ethiopia (4.5 million),[133] Kenya (2.4 million), and Djibouti (534,000).[134] A Somali diaspora is also found in parts of the Middle East, African Great Lakes region, Southern Africa, North America, Oceania, and Western Europe.

The Beja (Beja: Oobja; Arabic: البجا) are an ethnic group inhabiting Sudan, as well as parts of Eritrea and Egypt, in recent history they have lived primarily in the Eastern Desert. The Beja are traditionally Cushitic pastoral nomads native to northeast Africa numbering around 1,237,000 people.[135] Many Beja people speak the Beja language as a mother tongue, which belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. Some Beja groups have shifted to primary or exclusive use of Arabic. In Eritrea and southeastern Sudan, many members of the Beni Amer grouping speak Tigre.

The Agaw (Ge'ez: አገው Agäw, modern Agew) are an ethnic group inhabiting Ethiopia and neighboring Eritrea. They speak Agaw languages, which belong to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family. The Agaw are perhaps first mentioned in the third-century Monumentum Adulitanum, an Aksumite inscription recorded by Cosmas Indicopleustes in the sixth century. The inscription refers to a people called "Athagaus" (or Athagaous), perhaps from ʿAd Agaw, meaning "sons[136] of Agaw.

The Afar (Afar: Qafár), also known as the Danakil, Adali and Odali, are an ethnic group inhabiting the Horn of Africa. They primarily live in the Afar Region of Ethiopia and in northern Djibouti, although some also inhabit the southern point of Eritrea. Afars speak the Afar language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family. The Afar are traditionally pastoralists, raising goats, sheep, and cattle in the desert.[137] Socially, they are organized into clan families and two main classes: the asaimara ('reds') who are the dominant class politically, and the adoimara ('whites') who are a working class and are found in the Mabla Mountains.[138]

The Saho sometimes called "Soho",[139] are an ethnic group inhabiting the Horn of Africa. They are principally concentrated in Eritrea, with some also living in adjacent parts of Ethiopia. They speak Saho as a mother tongue, which belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family[140] and is closely related to Afar.

The Sidamo are an ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the Sidama Zone of the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNPR) in Ethiopia. They speak the Sidamo language which is a language of the Cushitic of the Afroasiatic language family. Despite their large numbers they currently lack a separate ethnic regional state.[141]

Ethiosemitic-speakers (language shift)

Many Ethiosemitic-language populations were historically Cushitic speakers, primarily of the Agaw branch.[142] Prominent examples of these include the Amhara, Gurage, Tigrayans, and Tigre. The Beta Israel historically spoke an Agaw language, subsequently followed by a language shift to Amharic and Tigrinya, and in the early 21st century to modern Hebrew due to acculturation into Israeli society. Ethiosemitic speaking groups generally have a cultural and genetic affinity to Cushitic speakers and are occasionally considered a sub-group of Cushitic peoples.[143]

Nilo-Saharan speakers (language shift, substantial Cushitic ancestry)

While having weaker cultural and ethnolinguistic ties to the Cushitic core, many populations in the Sudan and Southeastern Africa have significant Cushitic ancestry. Examples of these are Nubians, Sudanese Arabs, Kunama, Nara, the Samburu and Maasai.[144][145] Controversially, the Tutsi are thought to have a partial Nilo-Cushitic origin, although this is still being debated in academia.[146][147][148][149][150] Old Nubian had its source in the languages of the Nubian nomads who occupied the Nile between the first and third cataracts of the Nile and the Makorae nomads who occupied the land between the third and fourth cataracts following the collapse of Meroë sometime in the 4th century after being invaded by the Axumites. These Nilotic nomads also gave Nubia its name where before the 4th century, and throughout classical antiquity, Nubia was known as Kush, or, in Classical Greek usage, included under the name Ethiopia (Aithiopia). Early Egyptians referred to Nubia as "Ta-Seti," or "The Land of the Bow”.[151] Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a 1st-century CE travelogue written by a Greek merchant based in Alexandria writes about the “Berbers” (not to be confused with Berbers) of ancient North-East Africa, the first Barbara region extended from just south of Berenice Troglodytae in southeastern Egypt to just north of Ptolemais Theron in northeastern Sudan, whilst the second Barbara region was then located just beyond the Bab al-Mandeb up to the "Market and Cape of Spices, an abrupt promontory, at the very end of the Berber coast toward the east" found in northeastern Somalia.

Culture

Cushitic people have a wide diversity of cultures that relate to them specifically and as a group but as a whole tends to vary between sedentary agrarianism and nomadic pastoralism. Cushites, have been considerably influenced by Islam and to a somewhat lesser extent by Christianity.

The first century travel catalogue Periplus of the Erythraean Sea makes mention of nomads and settled cities in Barbara which referred to two ancient regions in littoral Northeast Africa. The two areas were inhabited by the Eastern Barbaroi or Baribah ("Berbers") or barbarians this could also be due to the fact of the ancient city of Berbera as called to by ancient Greek philosophers. These inhabitants were the ancestors of today's local Cushitic-speaking populations such as Somalis and Bejas. Indeed, the deep history of the nomadic lifestyle is apparent in that humans likely first domesticated dromedaries in Somalia or introduced there shortly after domestication in South Arabia. Somalia has the largest camel population in the world and is home to the ancient Laasgeel cave paintings depicting Somali nomads with their riches in livestock.[152][153][23][24]

Agriculture and Animal Husbandry

Coffee is a major export of Ethiopia and was first discovered and cultivated by Oromos in the region of Kaffa in Ethiopia and were the first to recognize the energizing effect of the coffee plant. Coffee was then primarily consumed in the Islamic world from where it later spread throughout the rest of the world. Coffee was even directly related to religious practices, for example, coffee helped its consumers fast in the day by helping them stay awake at night, during the Muslim celebration of Ramadan.

82% of the world Frankincense grows in Somalia, an industrial heritage of the ancient civilisation of Punt, famed for its incense, centered in modern-day Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Ethiopia where Frankincense was sold e.g to the ancient Egyptians. Dabqaad translates to censer in the Somali language and it's used to burn incense around the house for a fresh fragrance.

Music

Cushitic music uses a distinct modal system that is pentatonic, with characteristically long intervals between some notes. Tastes in music and lyrics are strongly linked in the Horn of Africa and Sudan.[154][155] Traditional singing presents diverse styles of polyphony (heterophony, drone, imitation, and counterpoint). Traditionally, lyricism is associated with the recitation of poetry.

Religion

Most inhabitants in the Horn of Africa follow one of the three major Abrahamic faiths. These religions have had a longstanding adherence in the region.

The ancient Axumite Kingdom produced coins and stelae associated with the disc and crescent symbols of the deity Ashtar.[156] The kingdom later became one of the earliest states to adopt Christianity, following the conversion of King Ezana II in the 4th century.

Islam was introduced to the northern Somali coast early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra whereupon Zeila's 7th century two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn was built and they were granted protection by the Aksumite King Aṣḥama ibn Abjar.[157][158][159] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[160] He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city,[160][92] suggesting that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th century. According to I.M. Lewis, the polity was governed by local Somali dynasties, who also ruled over the similarly-established Sultanate of Mogadishu in the littoral Benadir region to the south. Adal's history from this founding period forth would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighbouring Abyssinia.[92] The largest sample by Pew Research Center on Muslim affiliation in the Horn was attained in Ethiopia which found that 68% adhered to Sunnism, 23% were non-denominational Muslims, whilst another 4% adhere to other sects such as Shia, Quranist, Ibadi etc.[16]

Additionally, Judaism has a long presence in the region. The Kebra Negast ("Book of the Glory of Kings") relates that Israelite tribes arrived in Ethiopia with Menelik I, purported to be the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (Makeda). The legend relates that Menelik as an adult returned to his father in Jerusalem, and then resettled in Ethiopia, and that he took with him the Ark of the Covenant.[161] The Beta Israel today primarily follow the Orit (from Aramaic "Oraita" – "Torah"), which consists of the Five Books of Moses and the books Joshua, Judges and Ruth.

- Oriental Orthodoxy-Orthodox Tewahedo (Ethiopian Orthodoxy and Eritrean Orthodoxy)

- P'ent'ay: Ethiopian-Eritrean Evangelicalism (Evangelicalism - Protestantism)

- Catholicism (Eritrean Catholicism and Ethiopian Catholicism)

Other Religions

- Syncretism

- Waaqism (folk religions) and Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia formerly in some Cushitic groups.

Prior to the arrival of the Abrahamic religions, the majority of Cushitic peoples practiced 'folk religions'. At the center of this religion was the deity Waaq, who was said to inhabit the sky and who brought forth the seasonal rains. Although not widely practiced today, the remnants and vestiges of this religion are still to be found in the words and customs of the various Cushitic groups like the Oromo, Rendille and Somalis.[162] The Oromos, for instance, believed that Waaq sent protectors to his devoted followers called Ayyaana; these spirits would ward off any harm. This is directly connected to the traditional Somali names Ayaanle (masc) and Ayaan (fem), which means those who possess Ayaan or luck.[163][164] Also in Somalia there are many clans and places called Waaq; such as Ceel Waaq, which means "the well of Waaq" and Caabud Waaq, which means "where Waaq is worshiped". Some Somalis of the Darod clans still have Waaq names like the Jid Waaq clan, the Ogaden Tagaal Waaq sub-clan and the Majeerteen Siwaaqroon sub-clan. Also there are many Somali language uses of Waaq name, like Barwaaqo, which means "when the land is filled with grass and water". [(Waaqism/Waaqeffanna)].[165][166]

Genetics

Uniparental lineages

Cushitic ethnic groups have a diverse set of uniparental lineages. Nevertheless, certain commonalities can be observed.

Paternally, E-M35 (also known as E1b1b1, formerly E3b1) forms an important lineage in many Cushitic populations, other important paternal lineages in Cushitic populations include J-M267 (also known as J1), A-M13 (A1b1b2b, formerly A3b2), and T-M70 (T1a, formerly K2).[167][168][169][170][171][172]

Many Cushitic populations can be paternally traced back to having ethnic origins in the Nile Valley (Egypt and Northern Sudan) through haplogroup E-M78 and the Red Sea region of the Horn of Africa through haplogroup E-V1515.[25][26][27][28][29] This coincides with anthropological and linguistic hypotheses placing the ethnogensis of the Cushitic language family in the aforementioned regions.[173]

Maternally, Cushitic populations are more diverse, yet share certain lineages in common such as various East African-origin Macro-haplogroup L lineages (various L0, L1, L5, L2, L6, L4, L3 lineages) and North African and/or Middle Eastern-origin M1 and Macro-haplogroup N (in particular N subclades N1a, N1b, R0a, HV1b1, I, K1a, U3a, and U6a).[174][175][176]

Autosomal ancestry

Cushitic populations have existed at the cross-roads of Africa and Eurasia since the Stone Age, with the Nile acting as a corridor between sub-Saharan Africa and Levant and North Africa thus Cushitic populations have multiple origins, like most other populations, that have become idiosyncratic of Cushitic populations. Cushitic populations tend to combine in their ancestries both, genetic components indigenous to East Africa, and non-African components of West Asian origin. According to an autosomal DNA study by Hodgson et al. (2014), the Afro-Asiatic languages were likely spread across Africa and the Near East by an ancestral population(s) carrying a newly identified non-African genetic component, which the researchers dub the "Ethio-Somali" or "Semitic-Cushitic" in another study. This Ethio-Somali component is today most common among Cushitic and Ethiosemitic populations in the Horn of Africa and reaches a frequency peak among ethnic Somalis, representing the majority of their ancestry. The Ethio-Somali component is most closely related to the Maghrebi non-African genetic component, and is believed to have diverged from all other non-African ancestries at least 23,000 years ago. On this basis, the researchers suggest that the original Ethio-Somali carrying population(s) probably arrived in the pre-agricultural period from the Near East, having crossed over into northeastern Africa via the Sinai Peninsula. The population then likely split into two branches, with one group heading westward toward the Maghreb and the other moving south into the Horn.[54] Ancient DNA analysis indicates that this foundational ancestry in the Horn region is akin to that of the Neolithic farmers of the southern Levant.[177]

According to Hodgson et al. (2014), both the African ancestry (Ethiopic) and the non-African ancestry (Ethio-Somali) in Cushitic speaking populations is significantly differentiated from all neighboring African and non-African ancestries in East Africa, North Africa, the Levant and Arabia. The genetic ancestry of Cushitic and Semitic speaking populations in the Horn of Africa represents ancestries (Ethiopic and Ethio-Somali) not found outside of Cushitic and Semitic speaking HOA populations in any significance. Therefore, both ancestries are distinct, unique to, and considered the signature autosomal genetic ancestry of Cushitic and Semitic speaking HOA populations. Hodgson et al states:

"The African Ethiopic ancestry is tightly restricted to HOA populations and likely represents an autochthonous HOA population. The non-African ancestry in the HOA, which is primarily attributed to a novel Ethio-Somali inferred ancestry component, is significantly differentiated from all neighboring non-African ancestries in North Africa, the Levant, and Arabia."[54]

According to Hodgson et al. (2014), the non-African ancestry (Ethio-Somali) in the Cushitic speaking populations is distinct and unique to Cushitic and Semitic speaking HOA populations. Hodgson et al states:

"We find that most of the non-African ancestry in the HOA can be assigned to a distinct non-African origin Ethio-Somali ancestry component, which is found at its highest frequencies in Cushitic and Semitic speaking HOA populations."[54]

When calculated the genetic distance (FST) between Ethiosemitic-speaking and Cushitic-speaking Ethiopians, and populations of the Levant, North Africa, and the Arabian Peninsula using two approaches: (1) the whole genome and (2) only the non-African component—in the whole-genome analysis, Ethiopian Semitic and Cushitic populations appear to be closest to the Yemeni; when only the non-African component is used, they are closer to the Egyptians and populations inhabiting the Levant.[178] However this is due to the fact that the similarity is because of the Ethiopian contribution to the Yemeni gene pool. Pagani et al. (2012) states:

"The Ethiopian similarity with the Yemeni detected throughout the genome could be explained as an Ethiopian contribution to the Yemeni gene pool, consistent with that observed with mtDNA."[178]

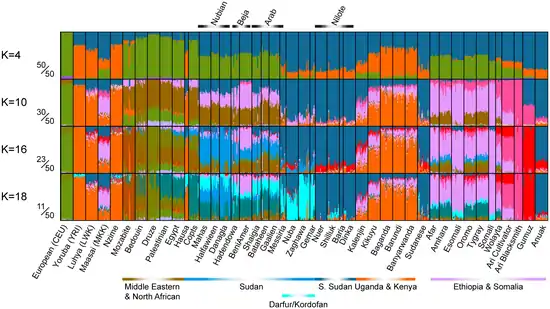

A 2015 study by Dobon et al. identified an ancestral autosomal component of West Eurasian origin that is common to many modern Afroasiatic-speaking populations in Northeast Africa. Known as the Coptic component, it peaks among Egyptian Copts who settled in Sudan over the past two centuries. The Coptic component evolved out of a main Northeast African and Middle Eastern ancestral component that is shared by other Egyptians and also found at high frequencies among Cushites (≈40–60%), with the remaining 40-60% of the ancestry of Cushites being of sub-Saharan East African origin. However, these percentages are not certain since Figure 3 of the study by Dobon et al. only features these percentages in the k=3 model.[102]

According to Dobon et al (2015), the results were not conclusive and states that there needs to be more studies on the East African samples. Dobon et al states:

"Our main results add new and interesting features to the North East African genetic complexity, with new populations that define a genetic component in southern Nilo-Saharan speakers that cannot be related to a North-African or other sub-Saharan components. These populations should be included in further population genetics and epidemiological studies to have a representative sample of the genetic diversity of the region of East Africa."[102]

The scientists involved in the study suggest that this points to a common origin for the general population of Egypt.[102] They also associate the Coptic component with Ancient Egyptian ancestry, without the later Arabian influence that is present among other Egyptians.[102] The Coptic component is roughly equivalent with the Ethio-Somali component.[54]

References

- Blench, Roger. Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman: Altamira, 2006 ISBN 9780759104662

- Diakonoff, Igor. The Earliest Semitic Society: Linguistic Data Journal of Semitic Studies, Vol. 43 Iss. 2 (1998).

- Shirai, Noriyuki. The Archaeology of the First Farmer-Herders in Egypt: New Insights into the Fayum Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic. Leiden University Press, 2010. ISBN 9789087280796.

- Blench R (2006) Archaeology, Language, and the African Past, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0-7591-0466-2, ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2, books.google.be/books?id=esFy3Po57A8C

- Ehret, Christopher; Keita, S. O. Y.; Newman, Paul (3 December 2004). "The Origins of Afroasiatic". Science. 306 (5702): 1680.3–1680. doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c. PMID 15576591. S2CID 8057990.

- Bender ML (1997), Upside Down Afrasian, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 50, pp. 19–34

- Militarev A (2005) Once more about glottochronology and comparative method: the Omotic-Afrasian case, Аспекты компаративистики – 1 (Aspects of comparative linguistics – 1). FS S. Starostin. Orientalia et Classica II (Moscow), p. 339-408. http://starling.rinet.ru/Texts/fleming.pdf

- Greenberg, Joseph (1963). The Languages of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University. pp. 48–49.

- Stevens, Chris J.; Nixon, Sam; Murray, Mary Anne; Fuller, Dorian Q. (July 2016). Archaeology of African Plant Use. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-315-43400-1.

- Cooper (2017).

- Rilly (2019), pp. 132-133.

- Rilly C (2010). "Recent Research on Meroitic, the Ancient Language of Sudan" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rilly, Claude (2008). "Enemy brothers. Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Between the Cataracts. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference for Nubian Studies Warsaw University 27 August-2 September 2006. Part 1. Main Papers. doi:10.31338/uw.9788323533269.pp.211-226. ISBN 9788323533269.

- Cooper, Julien (25 October 2017). "Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubia Until the Common Era". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4 (1). doi:10.5070/d64110028.

- Ambrose (1984), p. 234.

- https://www.pewforum.org/2012/08/09/the-worlds-muslims-unity-and-diversity-1-religious-affiliation/#identity

- Goulbourne, Harry (2001). "Who is a Cushi?". Race and Ethnicity: Solidarities and communities. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22501-4.

- Mandel, David (1 January 2010). Who's Who in the Jewish Bible. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-1029-3.

- Masudi's The Meadows of Gold (947 AD); Wahb ibn Munabbih (738) included among Cush's offspring "the "Qaran", the Zaghawa, the Habesha, the Qibt, and the Barbar".

- Andrew Paul (1954). A History of the Beja Tribes of the Sudan, p. 20

- The Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of Meroitic Script, UNESCO, p. 54.

- Lewis, M.I. (1979). The Cushitic-Speaking Peoples: A Jigsaw Puzzle for Social Anthropologists (PDF). London School of Economics. p. 138. ISBN 978-0520045743. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Bulliet, Richard (20 May 1990) [1975]. The Camel and the Wheel. Morningside Book Series. Columbia University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-231-07235-9.

As has already been mentioned, this type of utilization [camels pulling wagons] goes back to the earliest known period of camel domestication in the third millennium B.C.

- Richard, Suzanne (2003). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. ISBN 9781575060835. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- D’Atanasio, Eugenia; Trombetta, Beniamino; Bonito, Maria; Finocchio, Andrea; Di Vito, Genny; Seghizzi, Mara; Romano, Rita; Russo, Gianluca; Paganotti, Giacomo Maria (12 February 2018). "The peopling of the last Green Sahara revealed by high-coverage resequencing of trans-Saharan patrilineages". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1393-5. ISSN 1474-760X. PMC 5809971. PMID 29433568.

- Scozzari, Rosaria; Novelletto, Andrea; Coppa, Alfredo; Efremov, Georgi D.; Kozlov, Andrey I.; Brdicka, Radim; Assum, Guenter; Zagradisnik, Boris; Vona, Giuseppe (1 June 2007). "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–1311. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 17351267.

- Cruciani, Fulvio; Scozzari, Rosaria; Novelletto, Andrea; Valesini, Guido; Sellitto, Daniele; Akar, Nejat; Moral, Pedro; Dugoujon, Jean-Michel; Russo, Gianluca (1 July 2015). "Phylogeographic Refinement and Large Scale Genotyping of Human Y Chromosome Haplogroup E Provide New Insights into the Dispersal of Early Pastoralists in the African Continent". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (7): 1940–1950. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv118. PMC 4524485. PMID 26108492.

- "E-CTS10880 YTree". www.yfull.com. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ISOGG, Copyright 2016 by. "ISOGG 2017 Y-DNA Haplogroup E". isogg.org. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Ehret C (1995). Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09799-5.

- Ehret C (2002). The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85255-475-3.

- Ehret C (2002). "Language Family Expansions: Broadening our Understandings of Cause from an African Perspective". In Bellwood P, Renfrew C (eds.). Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

- Prendergast, Mary E.; Lipson, Mark; Sawchuk, Elizabeth A.; Olalde, Iñigo; Ogola, Christine A.; Rohland, Nadin; Sirak, Kendra A.; Adamski, Nicole; Bernardos, Rebecca; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Callan, Kimberly; Culleton, Brendan J.; Eccles, Laurie; Harper, Thomas K.; Lawson, Ann Marie; Mah, Matthew; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Stewardson, Kristin; Zalzala, Fatma; Ambrose, Stanley H.; Ayodo, George; Gates, Henry Louis; Gidna, Agness O.; Katongo, Maggie; Kwekason, Amandus; Mabulla, Audax Z. P.; Mudenda, George S.; Ndiema, Emmanuel K.; Nelson, Charles; Robertshaw, Peter; Kennett, Douglas J.; Manthi, Fredrick K.; Reich, David (5 July 2019). "Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa". Science. 365 (6448): eaaw6275. Bibcode:2019Sci...365.6275P. doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275. PMC 6827346. PMID 31147405.

- Bakano, Otto (24 April 2011). "Grotto galleries show early Somali life". AFP. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "Dr. Stuart Tyson Smith". ucsb.edu.

- Clark, John Desmond; Brandt, Steven A. (1 January 1984). From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04574-3.

- J. Clutton-Brook A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals 1999.

- Olsen, Sandra L. (1995) "Horses through time Boulder", Colorado: Roberts Rinehart Publishers for Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

- Mire, Sada (14 April 2015). "Mapping the Archaeology of Somalia: Religion, Art, Script, Time, Urbanism, Trade and Empire". African Archaeological Review. 32 (1): 111–136. doi:10.1007/s10437-015-9184-9. ISSN 0263-0338.

- Michael Hodd, East African Handbook, (Trade & Travel Publications: 1994), p.640.

- Ehret, Christopher (1982). Posnansky, Merrick (ed.). The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History. University of California Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0520045934. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- M. E. Prendergastet al, "Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa", Science, 30 May 2019

- B. M. Lynch and L. H. Robbins, "Cushitic and Nilotic Prehistory: New Archaeological Evidence from North-West Kenya", 22 January 2009

- Ambrose, Stanley H. (1984). From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa – "The Introduction of Pastoral Adaptations to the Highlands of East Africa". University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0520045743. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Christopher Ehret, Merrick Posnansky (ed.) (1982). The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History. University of California Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0520045934. Retrieved 4 December 2014.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Grillo, Katherine M.; Hildebrand, Elisabeth A. (June 2013). "The context of early megalithic architecture in eastern Africa: the Turkana Basin c. 5000-4000 BP". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 48 (2): 193–217. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2013.789188. S2CID 162193899.

- Lynch, B. M.; Robbins, L. H. (1978). "Namoratunga: The First Archeoastronomical Evidence in Sub-Saharan Africa". Science. 200 (4343): 766–768. Bibcode:1978Sci...200..766L. doi:10.1126/science.200.4343.766. JSTOR 1746628. PMID 17743241. S2CID 31531630.

- Hildebrand, Elisabeth A.; Shea, John J.; Grillo, Katherine M. (18 July 2013). "Four middle Holocene pillar sites in West Turkana, Kenya". Journal of Field Archaeology. 36 (3): 181–200. doi:10.1179/009346911X12991472411088. S2CID 54739651.

- Skoglund, Pontus; Thompson, Jessica C.; Prendergast, Mary E.; Mittnik, Alissa; Sirak, Kendra; Hajdinjak, Mateja; Salie, Tasneem; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Peltzer, Alexander; Heinze, Anja; Olalde, Iñigo; Ferry, Matthew; Harney, Eadaoin; Michel, Megan; Stewardson, Kristin; Cerezo-Román, Jessica I.; Chiumia, Chrissy; Crowther, Alison; Gomani-Chindebvu, Elizabeth; Gidna, Agness O.; Grillo, Katherine M.; Helenius, I. Taneli; Hellenthal, Garrett; Helm, Richard; Horton, Mark; López, Saioa; Mabulla, Audax Z. P.; Parkington, John; Shipton, Ceri; Thomas, Mark G.; Tibesasa, Ruth; Welling, Menno; Hayes, Vanessa M.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Ramesar, Raj; Meyer, Matthias; Pääbo, Svante; Patterson, Nick; Morris, Alan G.; Boivin, Nicole; Pinhasi, Ron; Krause, Johannes; Reich, David (21 September 2017). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell. 171 (1): 59–71.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. PMC 5679310. PMID 28938123.

- Collins, Alan S.; Pisarevsky, Sergei A. (August 2005). "Amalgamating eastern Gondwana: The evolution of the Circum-Indian Orogens". Earth-Science Reviews. 71 (3–4): 229–270. Bibcode:2005ESRv...71..229C. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.02.004.

- Richard Pankhurst, An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia, (Lalibela House: 1961), p.21

- Collins, Robert O., and James McDonald Burns. A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007.

- Walter RC, Buffler RT, Bruggemann JH, et al. (May 2000). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the last interglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–9. Bibcode:2000Natur.405...65W. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218. S2CID 4417823.

- Hodgson, Jason A.; Mulligan, Connie J.; Al-Meeri, Ali; Raaum, Ryan L.; Williams, Scott M. (12 June 2014). "Early Back-to-Africa Migration into the Horn of Africa". PLOS Genetics. 10 (6): e1004393. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004393. PMC 4055572. PMID 24921250.

- Ian Shaw & Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, London. 1995, p.231.

- Breasted 1906–07, p. 161, vol. 1.

- "Punt". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Flückiger, Friedrich August; Hanbury, Daniel (20 March 2014). Pharmacographia. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9781108069304.

- Wood, Michael (2005). In Search of Myths & Heroes: Exploring Four Epic Legends of the World. University of California Press. p. 155. ISBN 9780520247246.

opone punt.

- Sadler, Jr., Rodney (2009). "Put". In Katharine Sakenfeld (ed.). New Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. 4. Nashville: Abingdon Press. pp. 691–92.

- E. Naville, The Life and Monuments of the Queen in T.M. Davis (ed.), the tomb of Hatshopsitu, London: 1906. pp.28–29

- Breasted, John Henry (1906–1907), Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, collected, edited, and translated, with Commentary, p.433, vol.1

- Simson Najovits, Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2, (Algora Publishing: 2004), p.258.

- Dimitri Meeks – Chapter 4 – "Locating Punt" from the book Mysterious Lands", by David B. O'Connor and Stephen Quirke.

- Where Is Punt? Nova. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/egypt-punt.html

- Puntland profile, BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14114727

- Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. p. 948.

- War-Torn Societies Project International, Somali Programme (2001). Rebuilding Somalia: Issues and possibilities for Puntland. London: HAAN. p. 124. ISBN 978-1874209041.

- Patinkin, Jason (25 December 2016). "World's last wild frankincense forests are under threat". Yahoo Finance. Associated Press. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- Breasted 1906–07, p. 658, vol. II.

- 'A history of Egypt' Vol. I, p. 13 Moreover, The Making of Egypt (1939) states that the Land of Punt was "sacred to the Egyptians as the source of their race."

- Short History of the Egyptian People, by E. A. Wallis Budge. Budge stated that "Egyptian tradition of the Dynastic Period held that the aboriginal home of the Egyptians was Punt..."

- Breasted 1906–07, p. 451,773,820,888, vol. II.

- Joyce Tyldesley, Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh, Penguin Books, 1996 hardback, p.145

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.148

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, pp.145–146

- Kitchen, K. A. (1971). "Punt and how to get there". Orientalia. 40: 184–207 [190].

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.146

- O'Connor, David B (2003). Mysterious Lands. Routledge. pp. 88. ISBN 978-1844720040.

- Nadia Durrani, The Tihamah Coastal Plain of South-West Arabia in its Regional context c. 6000 BC – AD 600 (Society for Arabian Studies Monographs No. 4) . Oxford: Archaeopress, 2005, p. 121.

- Herausgegeben von Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, "Ge'ez". Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005, pp. 732.

- L'Arabie préislamique et son environnement historique et culturel: actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 24–27 juin 1987; page 264

- Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C; page 174

- Uhlig, Siegbert (ed.), Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. p. 185.

- Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 57.

- Phillipson (2009). "The First Millennium BC in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia and South–Central Eritrea: A Reassessment of Cultural and Political Development". African Archaeological Review. 26 (4): 257–274. doi:10.1007/s10437-009-9064-2. S2CID 154117777.

- The Pre-Aksumite and Aksumite Settlement of NE Tigrai, Ethiopia – Journal of Field Archaeology, 33:2, p.153

- Kitchen, A.; Ehret, C.; Assefa, S.; Mulligan, C. J. (29 April 2009). "Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1668): 2703–2710. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408. PMC 2839953. PMID 19403539.

- The Geography of Herodotus: Illustrated from Modern Researches and Discoveries by James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526

- John Kitto, James Taylor, The popular cyclopædia of Biblical literature: condensed from the larger work, (Gould and Lincoln: 1856), p.302.

- Society of Arts (Great Britain), Journal of the Society of Arts, Volume 26, (The Society: 1878), pp.912–913.

- Lewis, I.M. (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140.

- Rilly C (2010). "Recent Research on Meroitic, the Ancient Language of Sudan" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rilly C (January 2016). "The Wadi Howar Diaspora and its role in the spread of East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millenia BCE". Faits de Langues. 47: 151–163. doi:10.1163/19589514-047-01-900000010.

- Rilly, Claude (2008). "Enemy brothers. Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Between the Cataracts. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference for Nubian Studies Warsaw University 27 August-2 September 2006. Part 1. Main Papers. doi:10.31338/uw.9788323533269.pp.211-226. ISBN 9788323533269.

- Cooper, Julien (25 October 2017). "Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubia Until the Common Era". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4 (1). doi:10.5070/D64110028.

- Rowan, Kirsty (2011). "Meroitic Consonant and Vowel Patterning". Lingua Aegytia, 19.

- Rowan, Kirsty (2006), "Meroitic - An Afroasiatic Language?" SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 14:169–206.

- Rilly, Claude & de Voogt, Alex (2012). The Meroitic Language and Writing System. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107008663.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Rilly, Claude (2004). "The Linguistic Position of Meroitic" (PDF). Sudan Electronic Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- riley, claude. "The Wadi Howar Diaspora and its role in the spread of East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millenia BCE": 157. Retrieved 4 February 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dobon, Begoña; Hassan, Hisham Y.; Laayouni, Hafid; Luisi, Pierre; Ricaño-Ponce, Isis; Zhernakova, Alexandra; Wijmenga, Cisca; Tahir, Hanan; Comas, David; Netea, Mihai G.; Bertranpetit, Jaume (28 May 2015). "The genetics of East African populations: a Nilo-Saharan component in the African genetic landscape". Scientific Reports. 5: 9996. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E9996D. doi:10.1038/srep09996. PMC 4446898. PMID 26017457.

- Nancy C. Lovell, " Egyptians, physical anthropology of," in Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, ed. Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, ( London and New York: Routledge, 1999). pp 328–332

- Keita, S. O. Y. (26 July 2016). "Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. S2CID 144482802.

- Keita, S. O Y.; Boyce, A. J. (April 2008). "Temporal Variation in Phenetic Affinity of Early Upper Egyptian Male Cranial Series". Human Biology. 80 (2): 141–159. doi:10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[141:TVIPAO]2.0.CO;2. PMID 18720900.

- Terrazas Mata, Alejandro; Serrano Sánchez, Carlos (2013). "The late peopling of Africa according to craniometric data: a comparison of genetic and linguistic models". Human Evolution. 28 (1–2): 33–44. OCLC 855266155.

- Irish, Joel D. (1998). "Dental morphological affinities of Late Pleistocene through recent sub-Saharan and north African peoples". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris. 10 (3): 237–272. doi:10.3406/bmsap.1998.2517.

- "African Kingdoms 2500 BC to AD 350". 2014. The History Files. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- History of Blemmyes and nomads in southern Egypt and Nubia Archived 11 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Saudi Aramco World, May/June 1998.

- Ambrose, Stanley H. (1984). From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa - "The Introduction of Pastoral Adaptations to the Highlands of East Africa". University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0520045743. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Pontus Skoglund et al. "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure", Cell, 2017

- Excerpt from The 86th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (2017)

- Miller C, Doss M (31 December 1996). "Nubien, berbère et beja: notes sur trois langues vernaculaires non arabes de l'Égypte contemporaine" [Nubian, Berber and beja: notes on three non-Arabic vernacular languages of contemporary Egypt]. Égypte/Monde Arabe (in French) (27–28): 411–431. doi:10.4000/ema.1960. ISSN 1110-5097.

- Cooper, Julien (2017). "Conclusion". Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubian placenames in the Third and Second Millennium BCE: a view from Egyptian Records. Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 4 , Article 3. pp. 208–209. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

In antiquity, Afroasiatic languages in Sudan belonged chiefly to the phylum known as Cushitic, spoken on the eastern seaboard of Africa and from Sudan to Kenya, including the Ethiopian Highlands.

- Cooper, Julien (2017). "Conclusion". Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubian placenames in the Third and Second Millenium BCE: a view from Egyptian Records. Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 4 , Article 3. pp. 208–209. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

The toponymic data in Egyptian texts has broadly identified at least three linguistic blocs in the Middle Nile region of the second and first millennium BCE, each of which probably exhibited a great degree of internal variation. In Lower Nubia there was an Afroasiatic language, likely a branch of Cushitic. By the end of the first millennium CE this region had been encroached upon and replaced by Eastern Sudanic speakers arriving from the south and west, to be identified first with Meroitic and later migrations attributable to Nubian speakers.

- Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". Handbook of Ancient Nubia. ISBN 9783110420388. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

Two Afro-Asiatic languages were present in antiquity in Nubia, namely Ancient Egyptian and Cushitic.

- Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". Handbook of Ancient Nubia. ISBN 9783110420388. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

The Blemmyes are another Cushitic speaking tribe, or more likely a subdivision of the Medjay/Beja people, which is attested in Napatan and Egyptian texts from the 6th century BC on.

- Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". Handbook of Ancient Nubia. ISBN 9783110420388. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

From the end of the 4th century until the 6th century AD, they held parts of Lower Nubia and some cities of Upper Egypt.

- Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". Handbook of Ancient Nubia. ISBN 9783110420388. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

The Blemmyan language is so close to modern Beja that it is probably nothing else than an early dialect of the same language In this case, the Blemmyes can be regarded as a particular tribe of the Medjay.

- Robert Hetzron, "The Semitic Languages", 2013

- Wolf Leslau, "Sidamo is the substratum language of the Gurage speaking region. Sidamo influenced the Gurage cluster in the phonology, morphology, syntax, and mainly in the vocabulary." "Gurage Studies: Collected Articles", 1992

- Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia: A-C. p. 142.

- Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 26.

- Leslau, Wolf (1945). "The Influence of Cushitic on the Semitic Languages of Ethiopia a Problem of Substratum". WORD. 1 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1080/00437956.1945.11659246.

- Kebede, Messay (2003). "Eurocentrism and Ethiopian Historiography: Deconstructing Semitization". University of Dayton-Department of Philosophy. International Journal of Ethiopian Studies. Tsehai Publishers. 1: 1–19 – via JSTOR.

- Alemu, Daniel E. (2007). "Re-imagining the Horn". African Renaissance. 4 (1): 56–64 – via Ingenta.

- Rilly, Claude; de Voogt, Alex (2012). The Meroitic Language and Writing System. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-107-00866-3.

- Rilly C (June 2016). "Meroitic". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Kirsty Rowan. "Meroitic – an Afroasiatic language?". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.9638. Cite journal requires