Kanheri Caves

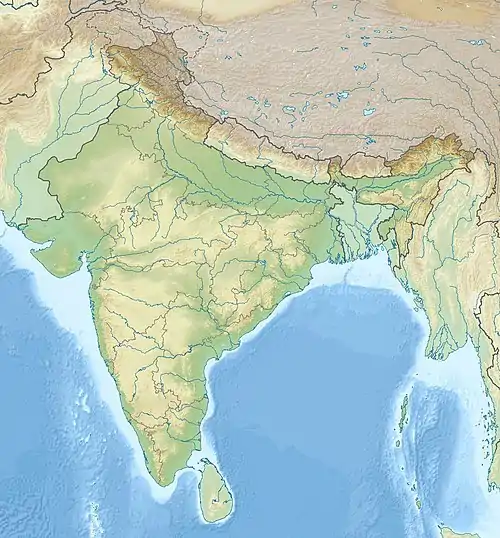

The Kanheri Caves (Kānherī-guhā) are a group of caves and rock-cut monuments cut into a massive basalt outcrop in the forests of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, on the former island of Salsette in the western outskirts of Mumbai, India. They contain Buddhist sculptures and relief carvings, paintings and inscriptions, dating from the 1st century CE[1] to the 10th century CE. Kanheri comes from the Sanskrit Krishnagiri, which means black mountain.[2]

| Kanheri Caves | |

|---|---|

| Kānherī-guhāḥ | |

| |

| |

| Location | Sanjay Gandhi National Park |

| Coordinates | 19°12′30″N 72°54′23″E |

| Geology | Basalt |

| Entrances | 109 |

The site is on a hillside, and is accessible via rock-cut steps. The cave complex comprises one hundred and nine caves. The oldest are relatively plain and unadorned, in contrast to later caves on the site, and the highly embellished Elephanta Caves of Mumbai. Each cave has a stone plinth that functioned as a bed. A congregation hall with huge stone pillars contains a stupa (a Buddhist shrine). Rock-cut channels above the caves fed rainwater into cisterns, which provided the complex with water.[3] Once the caves were converted to permanent monasteries, their walls were carved with intricate reliefs of Buddha and the Bodhisattvas. Kanheri had become an important Buddhist settlement on the Konkan coast by the 3rd century CE.[4]

Most of the caves were Buddhist viharas, meant for living, studying, and meditating. The larger caves, which functioned as chaityas, or halls for congregational worship, are lined with intricately carved Buddhist sculptures, reliefs, pillars and rock-cut stupas. Avalokiteshwara is the most distinctive figure. The large number of viharas demonstrates there was a well organized establishment of Buddhist monks. This establishment was also connected with many trade centers, such as the ports of Sopara, Kalyan, Nasik, Paithan and Ujjain. Kanheri was a University center by the time the area was under the rule of the Maurayan and Kushan empires.[2] In the late 10th century, the Buddhist teacher Atisha (980–1054) came to the Krishnagiri Vihara to study Buddhist meditation under Rahulagupta.[5]

Inscriptions at Kanheri

Nearly 51 legible inscriptions and 26 epigraphs are found at Kanheri, which include inscriptions in Brahmi, Devanagari and 3 Pahlavi[6] epigraphs found in Cave 90.[2][7] One of the significant inscriptions mentions the marriage of Satavahana ruler Vashishtiputra Satakarni with the daughter of Rudradaman I:[8]

"Of the queen ... of the illustrious Satakarni Vasishthiputra, descended from the race of Karddamaka kings, (and) daughter of the Mahakshatrapa Ru(dra)....... .........of the confidential minister Sateraka, a water-cistern, the meritorious gift.

— Kanheri inscription of Rudradaman I's daughter".[9]

There are also two inscriptions of Yajna Sri Satakarni (170-199 CE), in cave No. 81,[10] and in the Chaitya cave No. 3.[11]

A 494-495 CE inscription found at Kanheri mentions the Traikutaka dynasty.[12]

Description of the caves

The Island of Salsette, or Shatshashthi, at the head of Bombay harbour, is peculiarly rich in rock-Temples, there being works of this kind at Kanheri, Marol, Mahakali Caves, Magathane, Mandapeshwar Caves, and Jogeshwari Caves. The most extensive series is the group of Buddhist caves at Kanheri, a few miles from Thane, in which are about 109 separate caves, mostly small, however, and architecturally unimportant.[13]

From their position, within easy access from Bombay and Bassein, they early attracted attention, and were described by Portuguese visitors in the 16th century, and by European voyagers and travellers like Linschoten, Fryer, Gemelli Careri, Anquetil Du Perron, Salt and others.[13]

They are about six miles from Thana, and two miles north of the Tulsi lake, recently formed to increase the water supply of Bombay, and are excavated in one large bubble of a hill, situated in the midst of an immense tract of forest country. Most of the hills in the neighbourhood are covered with the jungle, but this one is nearly bare, its summit being formed by one large rounded mass of compact rock, under which a softer stratum has in many places been washed out by the rains, forming natural caves; it is in the stratum again below this that most of the excavations are situated. The rock in which the caves are is a volcanic breccia, which forms the whole of the hilly district of the island, culminating to the north of the caves in a point about 1,550 feet above the sea level.[13]

In so large a group there must be considerable differences in the ages of some of the excavations. These, however, may generally be at least approximatively ascertained from the characters of the numerous inscriptions that exist upon them. Architectural features are necessarily indefinite where the great majority of the excavations consist of a single small room, usually with a little veranda in front, supported by two plain square or octagonal shafts, and stone-beds in the cells. In the larger and more ornate caves they are, of course, as important here as elsewhere. Their style is certainly primitive, and some of these monks' abodes may date from before the Christian era.[13]

One small cave of this type (No. 81) in the ravine, consisting of a very narrow porch, without pillars, a room with a stone bench along the walls, and a cell to the left, has an inscription of Yajna Sri Satakarni of the Satavahanas of the 2nd century CE, and it is probable that numbers of others in the same plain style may range from the second to the fourth century. Others, however, are covered inside with sculpture of a late Mahayana type, and some have inscriptions which must date as late as the middle of the ninth century.[13]

The existence of so many monastic dwellings in this locality is partly accounted for by the neighbourhood of so many thriving towns. Among the places mentioned as the residences of donors to them, occur the names of Surparaka, the Supara of Greek and the Subara of Arab writers, the ancient capital of the northern Konkan; Kalyan, long a thriving port; Chemula, the Samylla of Greek geographers, on the island of Trombay; and Vasya perhaps Vasai or Bassein. Sri Staanaka or Thana itself, and Ghodabandar were also doubtless thriving towns.[13]

Cave No.1

Cave No.1 is a vihara, a Buddhist monastery. The entrance is framed by two large pillars. The cave has two levels, but its construction has never been completed.

| Cave No.1 | |

| |

Cave No.2

On the right of the court of the Great Chaitya is Cave No.2, pressing very closely upon it. It is a long cave, now open in front, and which contained three dagobas, one of them now broken off near the base. This cave are cave No.4 on both sides of the Great Chaitya are probably older than the Chaitya cave, which seems to have been thrust in between these two caves at a later date; but this long room has been so much altered at different times that it is not easy to make out its original arrangements. On the rock surrounding the dagoba are sculptures of Buddha, a litany, etc...., but all these are probably of later date.[13]

| Cave No.2 | |

| |

Great Chaitya (Cave No.3)

The cave first met on the way up the hill, and the most important one in the whole series, is the great Chaitya cave. On the jamb of the entrance to the veranda is an inscription of Yajna Sri Satakarni (circa 170 CE), the same whose name appears in cave No. 81; the inscription here being much mutilated, it is only by help of the other that it can be deciphered. It seems, however, to be integral, and it is consequently not improbable that the cave was excavated during his reign.[13]

From the style of the architecture it can be stated with certainty that the Cave 17[14] at Nasik Caves is contemporary, or nearly so, with the Great Chaitya at Karla, and that the Nahapana Cave there (No.10)[15] is a bit earlier than No.17, but at no great interval of time. The Gautamiputra Cave No.3 succeeded to these after a considerable lapse of time, while anything that Yajna Sri Satakarni may have done there must, of course, have been executed within a short interval of time after that. On the other hand, whatever its date may be, it is certain that the plan of this Chaitya Cave is a literal copy of that at Karle, but the architectural details show exactly the same difference in style as is found between Cave 17 and Cave 3 at Nasik.[13]

If, for instance, we compare the capitals in this cave, with those of Karle, we find the same degradation of style as is seen between Nasik cave No.10 and the later Nasik cave No.3. The screen too, in front of this cave, though very much weatherworn and consequently difficult to draw, is of very nearly the same design that is in the Gautamiputra Cave at Nasik, and in its complication of discs and animal forms seems almost as modern as what can be found at Amravati.[13]

This temple is 86.5 feet long by 39 feet 10 inches wide from wall to wall, and has thirty-four pillars round the nave and the dagoba, only 6 on one side and eleven on the other having bases and capitals of the Karle Chaitya-cave patterns, but not so well proportioned nor so spiritedly cut, while fifteen pillars round the apse are plain octagonal shafts. The dagoba is a very plain one, nearly 16 feet in diameter, but its capital is destroyed; so also is all the woodwork of the arched roof. The aisle across the front is covered by a gallery under the great arched window, and probably the central portion of the veranda in front was also covered, but in wood. At the ends of this veranda are two colossal figures of Buddha, about 23 feet high, but these appear to be considerably later than the cave itself.[13]

The sculpture on the front screen wall is apparently a copy of that in the same position at Karle, but rather better executed, indeed, they are the best carved figures in these caves; the rock in this place happens to be peculiarly close grained, and the style of dress of the figures is that of the age of the great Satakarnis. The earrings are heavy and some of them oblong, while the anklets of the women are very heavy, and the turbans wrought with great care. This style of dress never occurs in any of the later caves or frescoes. They may with confidence be regarded as of the age of the cave. Not so with the images above them, among which are several of Buddha and two standing figures of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteswara, which all may belong to a later period. So also does the figure of Buddha in the front wall at the left end of the veranda, under which is an inscription containing the name of Buddhaghosha, in letters of about the sixth century.[13]

The verandah has two pillars in front, and the screen above them is carried up with five openings above. In the left side of the court are two rooms, one entered through the other, but evidently of later date than the cave. The outer one has a good deal of sculpture in it. On each side of the court is an attached pillar; on the top of that on the west side are four lions, as at Karle; on the other are three fat squat figures similar to those on the pillar in the court of the Jaina Cave, known as Indra Sabha, at Ellora; these probably supported a wheel. In front of the verandah there has been a wooden porch.[13]

| Great Chaitya (Cave No.3) | |

| |

Cave No.4

On the left of the court of the Great Chaitya is a small circular cell containing a solid Dagoba, from its position almost certainly of more ancient date than this cave. On the right of the court of the Great Chaitya is Cave No.2. Both these caves are probably older than the Chaitya cave, which seems to have been thrust in between these two caves at a later date. On the rock surrounding the dagoba are sculptures of Buddha, a litany, etc...., but all these are probably of later date.[13]

| Cave No.4 | |

| |

South of the last is another Chaitya cave, but quite unfinished and of a much later style of architecture, the columns of the veranda having square bases and compressed cushion-shaped capitals of the type found in the Elephanta Caves. The interior can scarcely be said to be begun. It is probably the latest excavation of any importance attempted in the hill, and may date about the ninth or tenth century after Christ.[13]

Cave No.5 and cave No.6

These are not really caves but actually water cisterns. There is an important inscription over these (No 16 of Gokhale) mentioning that these were donated by a minister named Sateraka. The inscription also mentions the queen of Vashishtiputra Satakarni (130-160 CE), as descending from the race of the Karddamaka dynasty of the Western Satraps, and being the daughter to the Western Satrap ruler Rudradaman.[8]

"Of the queen ... of the illustrious Satakarni Vasishthiputra, descended from the race of Karddamaka kings, (and) daughter of the Mahakshatrapa Ru(dra)....... .........of the confidential minister Sateraka, a water-cistern, the meritorious gift."

— Kanheri inscription of Rudradaman I's daughter.[16]

Darbar Cave (Cave No.11)

To the north-east of the great Chaitya cave, in a glen or gully formed by a torrent, is a cave bearing the name of the Maharaja or Darbar Cave, which is the largest of the class in the group, and, after the Chaitya Caves, certainly the most interesting. It is not a Vihara in the ordinary sense of the term, though it has some cells, but a Dharmasala or place of assembly, and is the only cave now known to exist that enables us to realise the arrangements of the great hall erected by Ajatasatru in front of the Sattapanni Cave at Rajagriha, to accommodate the first convocation held immediately after the death of Buddha. According to the Mahawanso " Having in all respects perfected this hall, he had invaluable carpets spread there, corresponding to the number of priests (500), in order that being seated on the north side the south might be faced; the inestimable pre-eminent throne of the high priest was placed there. In the centre of the hall, facing the east, the exalted preaching pulpit, fit for the deity himself, was erected."[13]

The plan of the cave shows that the projecting shrine occupies precisely the position of the throne of the President in the above description. In the cave it is occupied by a figure of Buddha on a simhasana, with Padmapani and another attendant or chauri-bearers. This, however, is exactly what might be expected more than 1,000 years after the first convocation was held, and when the worship of images of Buddha had taken the place of the purer forms that originally prevailed. It is easy to understand that in the sixth century, when this cave probably was excavated, the "present deity" would be considered the sanctifying President of any assembly, and his human representative would take his seat in front of the image.[13]

In the lower part of the hall, where there are no cells, is a plain space, admirably suited for the pulpit of the priest who read Bana to the assembly. The centre of the hall, 73 feet by 32, would, according to modern calculation accommodate from 450 to 500 persons, but evidently was intended for a much smaller congregation. Only two stone benches are provided, and they would hardly hold 100, but be this as it may, it seems quite evident that this cave is not a Vihara in the ordinary sense of the term, but a Dharmasala or place of assembly like the Nagarjuni Cave.[13]

There is some confusion here between the north and south sides of the hall, but not in the least affecting the position of the President relatively to the preacher. From what we know, it seems, as might be expected, the Mahawanso is correct. The entrance to the hall would be from the north, and the President's throne would naturally face it.[13]

There are two inscriptions in this cave, but neither seems to be integral, if any reliance can be placed on the architectural features, though the whole cave is so plain and unornamented that this testimony is not very distinct. The pillars of the veranda are plain octagons without base or capital, and may be of any age. Internally the pillars are square above and below, with incised circular mouldings, changing in the centre into a belt with 16 sides or flutes, and with plain bracket capitals. Their style is that of the Viswakarma temple at Ellora, and even more distinctly that of the Chaori in the Mokundra pass. A Gupta Empire inscription has lately been found in this last, limiting its date to the fifth century, which is probably that of the Yiswakarma Cave, so that this cave can hardly be much more modern. The age, however, of this cave is not so important as its use. It seems to throw a new light on the arrangements in many Buddhist Caves, whose appropriation has hitherto been difficult to understand.[13]

Other caves

Directly opposite to it is a small cave with two pillars and two half ones in the veranda, having an inscription of about the 9th or 10th century on the frieze. Inside is a small hall with a rough cell at the back, containing only an image of Buddha on the back wall.[13]

The next, on the south side of the ravine, is also probably a comparatively late cave. It has two massive square pillars in the verandah, with necks cut into sixteen flutes as in the Darbar cave and some of the Elura Buddhist caves, it consequently is probably of the same age. The hall is small and has a room to the right of it, and in the large shrine at the back is a well cut dagoba.[13]

The next consists of a small hall, lighted by the door and a small latticed window, with a bench running along the left side and back and a cell on the right with a stone bed in it. The veranda has had a low screen wall connecting its two octagon pillars with the ends. Outside, on the left, is a large recess and over it two long inscriptions. Close to this is another cave with four benched chambers; possibly it originally consisted of three small caves, of which the dividing partitions have been destroyed; but till 1853 the middle one contained the ruins of four small dagobas, built of unbumt bricks. These were excavated by Mr. E. W. West, and led to the discovery of a very large number of seal impressions in dried clay, many of them enclosed in clay receptacles, the upper halves of which were neatly moulded somewhat in the form of dagobas, and with them were found other pieces of moulded clay which probably formed chhatris for the tops of them, making the resemblance complete.[13]

Close to the dagobas two small stone pots were also found containing ashes and five copper coins apparently of the Bahmani dynasty, and if so, of the 14th or 15th century. The characters on the seal impressions are of a much earlier age, but probably not before the 10th century, and most of them contain merely the Buddha creed.[13]

The next cave on the same side has a pretty large hall with a bench at each side, two slender square columns and pilasters in front of the antechamber, the inner walls of which are sculptured with four tall standing images of Buddha. The shrine is now empty, and whether it contained a structural simhasana or a dagoba is difficult to say.[13]

Upon the opposite side of the gulley is an immense excavation so ruined by the decay of the rock as to look much like a natural cavern; it has had a very long hall, of which the entire front is gone, a square antechamber with two cells to the left and three to the right of it. The inner shrine is empty. In front has been a brick dagoba rifled long ago, and at the west end are several fragments of caves; the fronts and dividing walls of all are gone.[13]

Cave 41

Some way farther up is a vihara with a large advanced porch supported by pillars of the Elephanta type in front and by square ones behind of the pattern occurring in Cave 15 at Ajanta. The hall door is surrounded by mouldings, and on the back wall are the remains of painting, consisting of Buddhas. In the shrine is an image, and small ones are cut in the side walls, in which are also two cells. In a large recess to the right of the porch is a seated figure of Buddha, and on his left is Padmapani or Sahasrabahu-lokeswara, with ten additional heads piled up over his own; and on the other side of the chamber is the litany with four compartments on each side. This is evidently a late cave.[13]

More caves

Altogether there are upwards of 30 excavations on both sides of this ravine, and nearly opposite the last-mentioned is a broken dam, which has confined the water above, forming a lake. On the hill to the north, just above this, is a ruined temple, and near it the remains of several stupas and dagobas. Just above the ravine, on the south side, is a range of about nineteen caves, the largest of which is a fine vihara cave, with cells in the side walls. It has four octagonal pillars in the veranda connected by a low screen wall and seat, and the walls of the veranda, and sides and back of the hall, are covered with sculptured figures of Buddha in different attitudes and variously accompanied, but with so many female figures introduced as to show that it was the work of the Mahayana school. There is reason, however, to suppose that the sculpture is later than the excavation of the cave.[13]

Behind and above these is another range, in some parts double, three near the east end being remarkable for the profusion of their sculptures, consisting chiefly of Buddhas with attendants, dagobas, etc... But in one is a fine sculptured litany, in which the central figure of Avalokiteswara has a tall female on each side, and beyond each are five compartments, those on the right representing danger from the elephant, lion, snake, fire, and shipwreck;[17] those on the left from imprisonment (?) Garuda, Shitala or disease, sword, and some enemy not now recognizable from the abrasion of the stone.[13]

Cave No.90

In Cave No.90 is a similar group representing Buddha seated on the Padmasana, on a lotus throne, supported by two figures with snake hoods, and surrounded by attendants in the manner so usual in the Mahayana sculptures of a later age in these caves. There are more figures in this one than are generally found on these compositions, but they are all very like one another in their general characteristics.[13]

Over the cistern and on the pilasters of the veranda are inscriptions which at first sight appear to be in a tabular form and in characters met with nowhere else; they are in Pahlavi.[13]

| Cave No.90 | |

| |

Lastly, from a point near the west end of this last range, a series of nine excavations trend to the south, but are no way remarkable.[13]

What strikes every visitor to these Kanheri caves is the number of water cisterns, most of the caves being furnished with its own cistern at the side of the front court, and these being filled all the year round with pure water. In front of many of the caves too there are holes in the floor of the court, and over their facades are mortices cut in the rock as footings for posts, and holdings for wooden rafters to support a covering to shelter the front of the caves during the monsoon.[13]

All over the hill from one set of caves to another steps are cut on the surface of the rock, and these stairs in many cases have had handrails along the sides of them.[13]

Passing the last-mentioned group and advancing southwards by an ancient path cut with steps wherever there is a descent, we reach the edge of the cliff and descend it by a ruined stair about 330 yards south of the great Chaitya cave. This lands in a long gallery extending over 200 yards south-south-east, and sheltered by the overhanging rock above. The floor of this gallery is found to consist of the foundations of small brick dagobas buried in dust and debris, and probably sixteen to twenty in number, seven of which were opened out by Mr. Ed. W. West in 1853.' Beyond these is the ruin of a large stone stupa, on which has been a good deal of sculpture, and which was explored and examined by Mr. West. In the rock behind it are three small cells also containing decayed sculptures, with traces of plaster covered with painting. Beyond this the floor suddenly rises about 14 feet, where are the remains of eleven small brick stupas; then another slight ascent lands on a level, on which are thirty-three similar ruined stupas buried in debris. Overhead the rock has been cut out in some places to make room for them. On the back wall are some dagobas in relief and three benched recesses. The brick stupas vary from 4 to 6 feet in diameter at the base, but all are destroyed down to near that level, and seem to have been all rifled, for in none of those examined have any relics been found.[13]

There were other large stupas in front of the great Chaitya cave, but these were opened in 1839 by Dr. James Bird, who thus described his operations "The largest of the topes selected for examination appeared to have been one time between 12 or 16 feet in height. It was much dilapidated, and was penetrated from above to the base, which was built of cut stone. After digging to the level of the ground and clearing away the materials, the workmen came to a circular stone, hollow in the centre, and covered at the top by a piece of gypsum. This contained two small copper urns, in one of which were some ashes mixed with a ruby, a pearl, small pieces of gold, and a small gold box, containing a piece of cloth; in the other a silver box and some ashes were found. Two copper plates containing legible inscriptions, in the Lat or cave character, accompanied the urns, and these, as far as I have yet been able to decipher them, inform us that the persons buried here were of the Buddhist faith. The smaller of the copper plates bears an inscription in two lines, the last part of which contains the Buddhist creed."[13]

On the east side of the hill are many squared stones, foundations, tanks, etc..., all betokening the existence at some period of a large colony of monks.[13]

Paintings in the caves

Cave number 34 has unfinished paintings of Buddha on the ceiling of the cave.

| Pilgrimage to |

| Buddha's Holy Sites |

|---|

|

| The Four Main Sites |

| Four Additional Sites |

| Other Sites |

|

| Later Sites |

Main entrance to the caves

Main entrance to the caves Cave 1

Cave 1 Cave 3

Cave 3 Spartan plinth beds

Spartan plinth beds Vihara - prayer hall

Vihara - prayer hall Kanheri Caves served as a center of Buddhism in Western India during ancient times

Kanheri Caves served as a center of Buddhism in Western India during ancient times Sculpture of Buddha in a temple at Kanheri Caves

Sculpture of Buddha in a temple at Kanheri Caves Cave sculpture of Buddha

Cave sculpture of Buddha Cave 41

Cave 41

References

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (June 1994). "Kanheri: The archaeology of an early Buddhist pilgrimage centre in western India" (PDF). World Archaeology. 26 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1080/00438243.1994.9980259.

- "Kanheri Caves". Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "Mumbai attractions". Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "Kanheri Caves Mumbai". Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- Ray, Niharranjan (1993). Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba in Bengali, Calcutta: Dey's Publishing, ISBN 81-7079-270-3, p. 595.

- West, E.W. (1880). "The Pahlavi Inscriptions at Kaṇheri". The Indian Antiquary. 9: 265–268.

- Ray, H.P. (2006). Inscribed Pots, Emerging Identities in P. Olivelle ed. Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-568935-6, p.127

- "A Note on Inscriptions in Bombay". Maharashtra State Gazetteers-Greater Bombay District. Government of Maharashtra. 1986. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Burgess, James; Bühler, Georg (1883). Report on the Elura cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina caves in western India; completing the results of the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons' operations of the Archaeological survey, 1877-78, 1878-79, 1879-80. Supplementary to the volume on "The cave temples of India.". London, Trübner & Co. p. 78.

- Burgess, James; Bühler, Georg (1883). Report on the Elura cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina caves in western India; completing the results of the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons' operations of the Archaeological survey, 1877-78, 1878-79, 1879-80. Supplementary to the volume on "The cave temples of India.". London, Trübner & Co. p. 79.

- Burgess, James; Bühler, Georg (1883). Report on the Elura cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina caves in western India; completing the results of the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons' operations of the Archaeological survey, 1877-78, 1878-79, 1879-80. Supplementary to the volume on "The cave temples of India.". London, Trübner & Co. p. 75.

- Geri Hockfield Malandra (1993). Unfolding A Mandala: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Ellora. SUNY Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9780791413555.

- Fergusson, James; Burgess, James (1880). The cave temples of India. London : Allen. pp. 348–360.

- Numbered as cave XII in Fergusson, p.271-272

- Numbered as cave VIII in Fergusson, p.270

- Burgess, James; Bühler, Georg (1883). Report on the Elura cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina caves in western India; completing the results of the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons' operations of the Archaeological survey, 1877-78, 1878-79, 1879-80. Supplementary to the volume on "The cave temples of India.". London, Trübner & Co. p. 78.

- Subramanian, Aditi (4 November 2019). "How ancient Indian sculptures tell the story of our ships". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kanheri Caves. |

- Nagaraju, S. (1981). Buddhist Architecture of Western India, Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

External links

- Archaeological Survey of India, "Kanheri Caves"

- Walking through the Historical Timeline of Buddhism

- Kanheri Caves

- Kanheri Caves Decoded is an online documentary video

- A detailed Review of Kanheri Caves and Sanjay Gandhi National Park: Read this before you go.

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)