Japanese occupation of British Borneo

Before the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, the island of Borneo was divided into five territories. Four of the territories were in the north and under British control – Sarawak, Brunei, Labuan, an island, and British North Borneo; while the remainder, and bulk, of the island, was under the jurisdiction of the Dutch East Indies.

Japanese-occupied British Borneo (British North Borneo, Brunei, Labuan and Sarawak) North Borneo (北ボルネオ, Kita Boruneo) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1945 | |||||||||||||||

Motto: Eight Crown Cords, One Roof (八紘一宇, Hakkō Ichiu) | |||||||||||||||

Japanese possessions in Borneo in 1943 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Military occupation by the Empire of Japan | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kuching[1][2] | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Japanese (official) Malay Chinese Bornean languages | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Military occupation | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||

• 1941–1945 | Shōwa (Hirohito) | ||||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||||

• 1941–1942 | Kiyotake Kawaguchi | ||||||||||||||

• 1942 | Toshinari Maeda | ||||||||||||||

• 1942–1944 | Masataka Yamawaki | ||||||||||||||

• 1944–1945 | Masao Baba | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||||||||

• Pacific War begins | 7 December 1941 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 December 1941 | |||||||||||||||

• British troops surrender | 1 April 1942 | ||||||||||||||

| 10 June 1945 | |||||||||||||||

| 15 August 1945 | |||||||||||||||

• British Military Administration set up | 12 September 1945 | ||||||||||||||

• Return to pre-war administrative position | 1 April 1946 | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1945 | 950000[note 1][3] | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Japanese-issued dollar ("Banana money") | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

On 16 December 1941, Japanese forces landed at Miri, Sarawak having sailed from Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina. On 1 January 1942, the Japanese navy landed unopposed in Labuan.[4] The next day, 2 January 1942, the Japanese landed at Mempakul on North Borneo territory. After negotiations as to the surrender of Jesselton with the Officers-in-charge of Jesselton and waiting for troop reinforcements, Jesselton was occupied by the Japanese on 8 January. However, it took the Japanese until the end of the month to conquer the entire territory of British Borneo. The Japanese subsequently renamed the northern part as North Borneo (北ボルネオ, Kita Boruneo), Labuan as Maida Island (前田島, Maeda-shima) and the neighbouring Dutch territories as South Borneo (南ボルネオ, Minami Boruneo).[5][6][7] For the first time in modern history all of Borneo was under a single rule.[8]

British Borneo was occupied by the Japanese for over three years. They actively promoted the Japanisation of the local population by requiring them to learn the Japanese language and customs. The Japanese divided the North Borneo into five provincial administrations (shus) and constructed airfields. Several prisoner of war camps were operated by the Japanese. Allied soldiers and most colonial officials were detained in them, together with members of underground movements who opposed the Japanese occupation. Meanwhile, local Malay leaders were maintained in position with Japanese surveillance and many foreign workers were brought to the territory.

Towards the end of 1945, Australian commandos were deployed to the island by US submarines with the Allied Z Special Unit conducting intelligence operations and training thousands of indigenous people to fight the Japanese in guerrilla warfare in the Borneo Campaign in preparation for the arrival of the main Allied liberation missions. Following landings in North Borneo and Labuan from 10 June 1945 by a combination of Australian and American forces, the island of Borneo was liberated. The British Military Administration formally took over from the Japanese on 12 September 1945.

Background

The Japanese intention to gain control of Borneo was associated with the concept of a unified Greater East Asia. This was developed by General Hachirō Arita, an army ideologist who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1936 to 1940.[9] Japanese leaders envisioned an Asia guided by Tokyo with no western interference and likened the Japanese Empire to an Asian equivalent of the Monroe Doctrine.[10] The island was seen by Japan as strategically important, being located on the main sea routes between Java, Sumatra, Malaya and the Celebes. Control of these routes was vital to securing the territory.[11][12]

With the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, Japanese immigrants had been welcomed since the 1900s. Companies such as Mitsubishi and Nissan were involved in trade with the territory.[7][11][13] Japanese immigrants had also been in the Raj of Sarawak since 1915, with some of them working as hawkers and some Japanese women working in the red-light district.[14] This presented opportunities for espionage, which were taken up by the Japanese military, especially from 1930.[11][15] Secret telegrams revealed that the Japanese ships docking regularly at Jesselton were engaged in espionage.[16] In 1940 the Americans and British had placed an embargo on exports of raw materials to Japan because of its continuing aggression in China and the Japanese invasion of French Indochina.[17][18][19][20] Chronically short of natural resources, Japan needed an assured supply, particularly of oil, in order to achieve its long-term goal of becoming the major power in the Pacific region.[14][21] Southeast Asia, which mostly consisted of European colonies, subsequently became a prime target for Japan. It hoped to obtain resources as well to ending the Western colonialism period.[22][23][24][25]

Invasion

The Japanese invasion plan called for the British territories to be taken and held by the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and the Dutch territories to the south by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN).[26] The IJA allocated the 35th Infantry Brigade to northern Borneo. The Brigade was led by Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi and consisted of units previously stationed at Canton in southern China.[27] On 13 December 1941, the Japanese invasion convoy left Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina, with an escort of the cruiser Yura, the destroyers of the 12th Destroyer Division, Murakumo, Shinonome, Shirakumo and Usugumo, submarine-chaser CH-7, and the aircraft depot ship Kamikawa Maru. Ten transport ships carried the advance party of the invasion force. The Support Force—commanded by Rear Admiral Takeo Kurita—consisted of the cruisers Kumano and Suzuya and the destroyers Fubuki and Sagiri.[28] The Japanese forces intended to capture Miri and Seria, then move on Kuching and the nearby airfields. The convoy proceeded without being detected and, at dawn on 16 December, two landing units secured Miri and Seria with little resistance from British forces.[28]

Kuala Belait and Lutong were captured on the same day with around 10,000 Japanese soldiers ashore.[25][28] On 22 December, Brunei Town was captured and the main Japanese force moved westwards towards Kuching after securing the oilfields in northern Sarawak. The Japanese air force bombed Singkawang airfield to deter any Dutch attack. After escorts drove off a lone Dutch submarine, the Japanese task force entered the mouth of the Santubong River on 23 December.[28] The convoy, including twenty transports carrying Japanese troops commanded by Colonel Akinosuke Oka, arrived off Cape Sipang and had completed disembarkation by the next morning. The 2nd Battalion of the 15th Punjab Regiment, which was stationed in Kuching, was the sole Allied infantry unit on the island. Although they resisted the Japanese attack on the airfield, they were soon outnumbered and retreated up the Santubong River. On 25 December, Japanese troops successfully captured Kuching airfield. The Punjab Regiment retreated through the jungle to the Singkawang area.[28]

After the Japanese secured Singkawang on 29 December, the rest of the British and Dutch troops retreated further into the jungle, moving south to Sampit and Pangkalanbun, where a Dutch airfield was located at Kotawaringin. On 31 December a force under Lieutenant Colonel Genzo Watanabe moved northward to occupy the remainder of Brunei, Beaufort and Jesselton.[28] Jesselton was defended by the North Borneo Armed Constabulary with 650 men. They provided little resistance and the town was taken on 9 January.[29] On 3 January 1942 the IJA invaded Labuan Island. On 18 January, using small fishing boats, the Japanese landed at Sandakan, the seat of government of British North Borneo. On the morning of 19 January Governor Charles Robert Smith surrendered British North Borneo and was interned with his staff. The occupation of British Borneo was thus completed. The Dutch southern and central Borneo were also taken by the IJN, following its attacks from east and west. After ten weeks in the jungle-covered mountains, Allied troops surrendered on 1 April.[28]

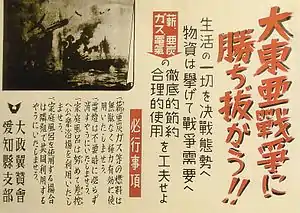

Propaganda and assimilation

.jpg.webp)

The Tokyo-based Asahi Shimbun newspaper and the Osaka-based Mainichi Shimbun began publication in Malay in both Borneo and the Celebes Island, carrying news on behalf of the Japanese government.[12] Following their occupation, the Japanese began a process of assimilation of the local people. Propaganda was displayed throughout the Bornean territories and slogans such as "Asia for Asians" and "Japan, the light of Asia" were widely displayed.[30] Ethnocentrism was central to this plan with Japanese values, world view, culture, spirit, emperor worship and racial superiority being promulgated.[31]

As part of the process of Japanisation (Nipponisation), schoolchildren and adults were instructed to go to nihon-go classes to learn the Japanese language.[30] Students had to wear uniforms and a peaked cap with a blue sakura (cherry blossom) emblem, which was replaced by a red one as the students attained higher grades.[32] Each morning students were required to sing the Japanese national anthem with gusto followed by bowing to the Japanese flag before marching to their classrooms.[32] This was done to make the population "think, feel and act like Japanese East Asians". Their treatment of the local indigenous people and Chinese immigrants differed.[33] Attempting to ensure the indigenous local were not their enemies an administrative directive on 14 March 1942 declared that:

Local customs, practices and religions shall not be interfered with for the time being. The impact of the war on native livelihood should be alleviated where possible and within the limits set by the need for rendering occupational forces self-sufficient and securing resources vital to national defence. However, no measures shall be taken for the sole purpose of placating the natives. [Emphasis added.][33]

A different principle applied to the local Chinese as they were considered to be the only community which could offer a serious challenge to Japanese authority:

The main objective, where the local Chinese are concerned, shall be to utilise their existing commercial organisations and practices to the advantage of our policies ... and measures shall be taken to sever political ties among the Chinese residents of the various areas as well as between them and mainland China.[33]

Attempts were also made to inculcate anti-Western feeling with local government officers required to attend Japanese night classes. Unlike his counterparts in North Borneo and Sarawak which were previously ruled by European officials, the Brunei Sultan, Ahmad Tajuddin, was retained by the Japanese with no reduction in salary. Malay government officials were usually retained in their posts.[34]

Administration

Administrative areas

Under the Japanese occupation British Borneo were divided into five provinces (shūs):[6][35][36]

- Kyūchin-shū (久鎮州): Sarawak First and Second Divisions, Pontianak and Natuna Islands.[note 2]

- Shibu-shū (志布州): Sarawak Third Division

- Miri-shū (美里州): Sarawak Fourth and Fifth Divisions, Brunei Town.

- Seigan-shū (西岸州): Western North Borneo of Api, Beaufort, Kota Belud, Kota Marudu, Keningau, Weston and Labuan.

- Tōgan-shū (東岸州): Eastern North Borneo of Elopura, Beluran, Lahad Datu and Tawau.

Each of the five shūs had a Japanese provincial governor, or the administration remained in the hands of the local people with Japanese surveillance.[37] Each of the provinces constituted prefectures or ken (県).[35] Jesselton and Sandakan were renamed Api and Elopura respectively.[38]

Occupation forces

Once Sarawak was secured, control of the rest of British Borneo fell to the Kawaguchi Detachment, while neighbouring Dutch Borneo was administered by the IJN.[5] In mid-March 1942, the navy detachment was redeployed to Cebu. The 4th Independent Mixed Regiment, also known as the Nakahata Unit, under Colonel Nakahata Joichi took over the tasks of mopping up operations, maintaining law and order, and establishing a military government. On 6 April 1942, the unit came under Lieutenant General Marquess Toshinari Maeda's Borneo Defence Army who became responsible for the area. His headquarters was initially at Miri, but Maeda considered it unsuitable and moved to Kuching.[39] In July the Nakahata Regiment was reorganised into two 500-man battalions, the 40th and 41st Independent Garrison Infantry Battalions. Maeda was killed along with Major Hataichi Usui and Pilot-Captain Katsutaro Ano in an air crash while flying to Labuan Island on 5 September 1942.[12] The Japanese then renamed the island Maeda Island (前田島, Maeda-shima) in remembrance to him.[35] Maeda was replaced by Lieutenant General Masataka Yamawaki from 5 September 1942 to 22 September 1944.[12]

By 1943 the battalions combined strength had reduced to 500 men. The military government moved its headquarters again in April 1944 to Jesselton. Yamawaki was formerly Director of the Resources Mobilisation Bureau; his appointment in 1942 was interpreted by the Allies as part of a drive to establish Borneo as a significant location for storage of supplies and the development of supporting industry.[12] Law enforcement in Borneo fell to the notorious Kenpeitai, the Japanese military police, who were directly responsible to the military commander and the Japanese War Ministry. They had virtually unlimited power and frequently used torture and brutality. The Kenpeitai headquarters were in a two-storey bungalow on Java Street (Jalan Jawa), Kuching.[2][40][41] From April 1944 it was relocated to the Sports Club Building in Api. Japanese justice became synonymous with punishment out of all proportion to the offence. They revived the pre-war civil court system from November 1942, with local magistrates applying the Sarawak Penal Code.[42] With the Allied advance in the Pacific, the Japanese realised that Borneo was likely to be retaken. The Borneo Defence Army was strengthened with additional units and renamed 37th Army. Command passed to Lieutenant General Masao Baba from 26 December 1944.[43]

Military infrastructure and bases

.jpg.webp)

Airfields were constructed by prisoners of war and conscripted labour from various locations, including from Brunei, Labuan, Ranau and Elopura.[44][45] Before the Japanese occupation, there were only three airfields: in Kuching; Miri; and Bintulu in Sarawak, while in North Borneo there were none.[46] Due to this, the Japanese planned to construct a total of twelve airfields in different parts of northern Borneo to strengthen its defence, of which seven were to be located in Api, Elopura, Keningau, Kudat, Tawau, Labuan and Lahad Datu.[46] The Japanese also launched a series of road projects in North Borneo, with the roads linking Ranau with Keningau and Kota Belud with Tenghilan to be improved as well a new road linking Kudat and Kota Belud to be constructed. As these roads passed through mountainous areas, a large number of forced labourers were needed to realise the projects.[46] In preparing for Allied retaliation Lieutenant general Masataka Yamawaki created an indigenous force consisting of around 1,300 men in 1944. Most of them were stationed in Kuching, with others in Miri, Api and Elopura; all were tasked to maintain peace and order, gather intelligence and to recruit.[47] Brunei harbour was also used by the IJN as a refuelling depot and as a staging post for the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[48]

Prisoner of war camps

The Japanese had major prisoner of war (POW) camps at Kuching, Ranau, and Sandakan, plus smaller ones at Dahan and other locations. Batu Lintang camp held both military and civilian prisoners. The camp was finally liberated on 11 September 1945 by elements of the Australian 9th Division under the command of Brigadier Tom Eastick. Sandakan camp was closed by the Japanese prior to the Allied invasion; most of its occupants died as a result of forced marches from Sandakan to Ranau. In total the Japanese are believed to have held an estimated 4,660 prisoners and internees at all camps in northern Borneo, with only 1,393 surviving to end of the war.[49][50][51]

Effects of occupation

Economy

Following the occupation government offices re-opened on 26 December 1941.[52] Japanese companies were brought in and granted monopolies in essential goods. In early 1942 the first branch of Yokohama Specie Bank opened in Kuching in the former building of Chartered Bank. The Japanese Southern Development Treasury also opened an office to oversee investment throughout northern Borneo. Two Japanese insurance companies, Tokyo Kaijo Kasai and Mitsubishi Kaijo Kasai, began operations.[52]

All motor vehicles were confiscated by Japan Transport Co. for limited compensation. The Japanese recruited labours to construct airfields for extra food and payment, while detainees were forced to work.[52] The POWs who worked to build the airstrip also received a small salary weekly, typically enough to purchase an egg.[53] Together with the rest of Southeast Asia, Japan exploited Borneo as a source of raw materials.[54] The Japanese authorities enforced a food self-sufficiency policy. Priority for all resources including foodstuffs was given to Japanese troops with only a limited ration available for the local population. Through Mitsui Morin and Mitsui Bussan, foodstuffs such as rice, maize, tapioca, sweet potatoes and coconut oil were monopolised. Sago supplies were controlled by the Mitsubishi's Tawau Sangyo.[55] Stealing and smuggling were punishable by death. The IJA and the IJN attempted to rebuild the oil industry to contribute to Japan's war effort.[31]

The Japanese particularly exploited the Chinese community, mainly due to their support for the Kuomintang and contributions to the China Relief Fund and British war efforts. The elites in major towns bore the heaviest burden and those with lesser resources went bankrupt.[56] The military government strictly controlled Chinese businesses, those who were unwilling were forcibly encouraged.[55] Japanese policy in this area was summarised in Principles Governing the Implementation of Measures Relative to the Chinese [Kakyō Kōsaku Jisshi Yōryō] issued by the Japanese headquarters in Singapore in April 1942.[56]

.jpg.webp)

Before the invasion, the Japanese government had printed unnumbered military yen notes for use in all occupied territories in Southeast Asia.[57][58] Increasing inflation coupled with Allied disruption of Japan's economy forced the Japanese administration to issue banknotes of larger denominations and increase the amount of money in circulation. From January 1942 the Japanese set the military notes at par with the national yen.[59]

Residents

.JPG.webp)

Effects of the occupation among the local population varied widely. The Japanese allowed Malay officials to maintain their positions in the civil service,[34] but generally Malays were abused together with the Chinese and the indigenous peoples. In response to a directive from Singapore in 1942, the poor treatment of indigenous people began to be alleviated as they were not perceived to be the main enemies of Japan.[33]

With the sparse and widely dispersed local population in northern Borneo, the Japanese military administration had little choice but rely to forced labour from abroad, mainly from elsewhere in the Dutch East Indies and occupied China, under the management of the North Borneo Labour Business Society (Kita Boruneo Romukyokai).[60] Chinese skilled workers were brought from Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shantou, and Indonesians from Java. Although all workers were provided with board and lodging, the Chinese received better treatment as they were considered to be the more skilled workers.[60] Most of the Javanese workers were sent to Brunei,[61] while the more skilled Chinese workers were employed in boat-building in Kuching and Elopura.[60] Young Chinese males attempted to avoid being captured for forced labour, while young Chinese females were terrified of being taken as comfort women.[62] Many coastal inhabitants fled to avoid these threats. A search for Chinese agitators on the Mantanani Islands in February 1944 led to the mass killing of 60 Suluk and several Chinese civilians.[63]

As both Korea and Taiwan had been under the domination of Japan for decades, many citizens of both territories were forced to work for the Japanese military under harsh conditions.[64] A number were sent to Borneo to work as prison guards, replacing the existing Japanese guards. They received no training for the treatment of POWs and many were involved in brutalising the prisoners, whose treatment deteriorated after the replacement of Japanese guards in Elopura by the Taiwanese in April 1943.[64]

Resistance

Albert Kwok

On the west coast of North Borneo, a resistance movement developed led by Albert Kwok, a Chinese from Kuching, who after working with the China Red Cross moved to Jesselton in 1940.[65] He collaborated with local indigenous groups in North Borneo.[66] After establishing contact with American forces in the Philippines Kwok travelled to Tawi-Tawi for training. He returned with three pistols, a box of hand grenades and a promise of further weapons.[67] However, the promised weapons were not delivered and Kwok had to launch a revolt with his locals armed with only knives and spears.[68]

Though they were poorly equipped, the attack still managed to kill at least 50 Japanese soldiers and temporarily capture Api, Tuaran and Kota Belud in early November.[2][69][70] As the Japanese began to retaliate, Kwok's force retreated to their hide-out.[71] The Japanese launched ruthless counter-measures, bombing coastal settlements and machine-gunning local people.[70][72] Almost all villages in the area were burnt down and 2,000–4,000 civilians were executed.[73][74] The Japanese threatened further mass civilian killings and so Kwok surrendered with several of his senior aides. They were executed on 21 January 1944 in Petagas, Putatan. After the failed uprising the Japanese conducted regular reprisals. The inhabitants of North Borneo were unable to organise a further uprising due to the level of Japanese surveillance.[75][76]

Force Z

As part of the Borneo Campaign Australian commandos were landed using US submarines.[77] The Allied Z Special Unit began to train Dayak people from the Kapit Division in guerrilla warfare. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers. They also provided intelligence vital to securing Japanese-held oil fields and to facilitating the landings of Australian forces in June 1945. Most of the Allied activities were conducted under two intelligence and guerrilla warfare operations: Operation Agas in North Borneo; and Operation Semut in Sarawak.[78] Tom Harrisson, a British anthropologist, journalist and co-founder of Mass-Observation was among those parachuted in to work with the resistance.[79]

Liberation

The Allies organised a liberation mission known as the Operation Oboe Six to reconquer the northern part of Borneo. This followed their success with Operations Oboe One and Oboe Two.[80][81] Under the cover of a naval and aerial bombardment, the 9th Australian Division landed on Borneo and Labuan on 10 June with a force of around 14,000 personnel.[81] With narrow roads and swampy conditions near the island beaches, the unloading operations by Royal Australian Engineers were hampered. Landings in the Brunei Bay area went more easily. The prediction of strong Japanese resistance proved inaccurate, with only few air raids against the Allied forces.[82]

The 24th Infantry Brigade, part of the 9th Division, landed at the southern end of Labuan, near the entrance of Brunei Bay, and commanding the approach to northern Borneo.[83] The 20th Infantry Brigade landed near Brooketon, on a small peninsula at the southern end of the bay.[83] The 20th Infantry Brigade rapidly secured Brunei Town against relatively light opposition, suffering only 40 casualties in the campaign. The 24th Infantry Brigade encountered stronger opposition in taking Labuan,[81] where the defenders withdrew to an inland stronghold and held out among dense jungle-covered ridges and muddy swamps. To subdue the Japanese resistance an intense naval and artillery bombardment was laid down over the course of a week before an assault was put in by two companies of infantry supported by tanks and flamethrowers.[83]

After securing Labuan, the 24th Infantry Brigade was landed on the northern shore of Brunei Bay on 16 June, while the 20th Infantry Brigade continued to consolidate the southern lodgement by advancing south-west along the coast towards Kuching.[84] The 2/32nd Battalion landed at Padas Bay and seized the town of Weston before sending out patrols towards Beaufort, 23 kilometres (14 mi) inland. The town was held by around 800–1,000 Japanese soldiers and on 27 June an attack was carried out by the 2/43rd Battalion.[84] Amid a torrential downpour and in difficult terrain, the 2/32nd Battalion secured the south bank of the Padas River. Meanwhile one company from the 2/43rd was sent to take the town and another marched to the flanks, to take up ambush positions along the route that the Japanese were expected to withdraw along. The 2/28th Battalion secured the lines of communication north of the river.[85]

On the night of 27/28 June, the Japanese launched six counter-attacks. Amid appalling conditions, one Australian company became isolated and the next morning another was sent to attack the Japanese from the rear.[86] Fighting its way through numerous Japanese positions, the company killed at least 100 Japanese soldiers and one of its members, Private Tom Starcevich was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his efforts.[86] Following this, the Japanese withdrew from Beaufort and the Australians began a slow, cautious advance, using indirect fire to limit casualties. By 12 July they occupied Papar,[87] and from there sent out patrols to the north and along the river until the cessation of hostilities.[88] In August the fighting came to an end. The division's total casualties in the operation were 114 killed and 221 wounded, while the Japanese losses were at least 1,234.[84][89]

.jpg.webp) Australian troops from the 2/43rd Battalion advance with a Matilda tank on Maeda-shima in a sweep mission to clear the area of Japanese troops, 12 June 1945

Australian troops from the 2/43rd Battalion advance with a Matilda tank on Maeda-shima in a sweep mission to clear the area of Japanese troops, 12 June 1945 Members of the Australian 2/17th Battalion inspecting the bodies of dead Japanese soldiers in Brunei during an operation on 13 June 1945

Members of the Australian 2/17th Battalion inspecting the bodies of dead Japanese soldiers in Brunei during an operation on 13 June 1945 Indigenous peoples carrying Japanese rifles walking along a street in Brunei on their return to their villages on 17 June 1945

Indigenous peoples carrying Japanese rifles walking along a street in Brunei on their return to their villages on 17 June 1945

Aftermath

Japanese surrender

After the surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945 Lieutenant General Masao Baba, commander of Japanese forces in northern Borneo, surrendered at Layang-layang beach of Labuan on 9 September. He was then brought to the headquarters of Australian 9th Division, where at the official surrender ceremony on 10 September he signed the surrender document and handed over his sword to the divisional commander, Major General George Wootten.[90][91] The location became known as Surrender Point.[92]

It was estimated that around 29,500 Japanese remained on the island. 18,600 belonged to the IJA, 10,900 to the IJN.[93] The greatest concentrations of Japanese troops were in the interior.[94] There were some Japanese who refused to surrender and moved further inland. After calls from Lieutenant general Baba they also surrendered.[95] The Japanese repatriation following the surrender took several months, delayed due to lack of shipping. It was supervised by the Australians as Borneo along with New Guinea, Papua and the Solomon Islands were under their authority.[96] Australian forces also supervised the destruction of Japanese weapons and ammunition and the evacuation of internees and Allied POWs from Japanese camps.[97]

The British Military Administration (BMA) took over the task of management from the Australians on 12 September 1945 and summarised the situation towards the end of October:

In North Borneo and Labuan the destruction of coastal townships was almost total, and in Brunei the shop quarter and many Government buildings were completely destroyed. The oilfields at Seria in Brunei were also heavily damaged, the last well fire there having been extinguished on the 27th September.... Brunei and Labuan, Miri, Beaufort and Weston which were focal points in the attack suffered heavily from preliminary bombardments. Bintulu was deserted and the airstrip there had been entirely destroyed. Kuching, apart from minor damage in the bazaar area was practically untouched. In Sibu the town area was severely damaged.... Both Jesselton and Sandakan in particular were heavily damaged...[98]

The observation revealed that despite the destruction caused by the Allied bombardments, there were few Japanese casualties.[98] Widespread malnutrition and disease amongst the population was caused by acute food shortages.[99] In response the BMA provided food and medical supplies and reconstructed the public infrastructure, including roads, bridges, the rail network, sewerage and water supplies.[98]

.JPG.webp) Baba signs the surrender document in Labuan, British Borneo, being watched by Australian Major General George Wootten and other Australian units on 10 September 1945

Baba signs the surrender document in Labuan, British Borneo, being watched by Australian Major General George Wootten and other Australian units on 10 September 1945 Disarmed Japanese troops marching towards a prisoner of war compound in Api after surrendering to the Australians on 8 October 1945

Disarmed Japanese troops marching towards a prisoner of war compound in Api after surrendering to the Australians on 8 October 1945.JPG.webp) Japanese civilians and soldiers leaving North Borneo after the surrender of Japan

Japanese civilians and soldiers leaving North Borneo after the surrender of Japan

War crimes trials

The Australians held war crime trials on Labuan from 3 December 1945 to 31 January 1946. There were 16 trials involving 145 alleged war criminals, and these resulted in 128 convictions and 17 acquittals.[100] Lieutenant Colonel Tatsuji Suga, who had been responsible for the Batu Lintang camp administration, believing that his entire family had been killed during the US atomic bombing of Hiroshima committed suicide before his trial's conclusion.[14] Captain Susumi Hoshijima, who was responsible for the administration of Sandakan camp, was found guilty of war crimes and hanged in Rabaul, New Guinea in 1946.[101]

Many Korean and Taiwanese who had been prison guards were tried in the minor war crimes trials. In Sandakan 129 Taiwanese guards were found guilty of brutalising POWs and 14 were sentenced to death.[64] The International Military Tribunal for the Far East concluded that during the resistance movement in North Borneo the military police were involved in torturing and killing hundreds of Chinese in an apparently systematic attempt to exterminate the Suluk coastal population.[102][103] The last commander of the Japanese army in northern Borneo, Masao Baba, was charged on 8 March 1947 with command responsibility for the Sandakan death marches that caused the death of over 2,000 Allied POWs and brought to Rabaul for trial.[104] During the trial he confessed to being aware of the weakened condition of the prisoners but still issuing direct orders for a second march.[105] The trial concluded on 5 June with a death sentence;[106][107] Baba was hanged on 7 August 1947.[108]

Presiding members of the war crimes trials in Labuan on 20 December 1945

Presiding members of the war crimes trials in Labuan on 20 December 1945 Captain Susumi Hoshijima (centre) during the war crimes trial in Labuan, January 1946. He was found guilty of causing the deaths of POWs at Sandakan camp and subsequently hanged in 1946.[101]

Captain Susumi Hoshijima (centre) during the war crimes trial in Labuan, January 1946. He was found guilty of causing the deaths of POWs at Sandakan camp and subsequently hanged in 1946.[101]

Honours and legacy

War memorials

To honour the sacrifices of fallen liberators during operations for the recovery of Borneo, a cemetery named the Labuan War Cemetery was constructed and maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.[109] The cemetery holds the graves of 3,908 soldiers, including some POWs from Borneo and the Philippines. Most of the graves are unidentified, the 1,752 identified graves lists 1,523 soldiers, 220 airmen, five sailors and four civilians; 858 Australians, 814 British, 43 Indians, 36 Malayans and 1 New Zealander as well as members of the local forces from North Borneo, Brunei and Sarawak.[109] 34 Indian soldiers, whose remains were cremated, are commemorated on a memorial in the Indian army plot. Each grave was originally marked with a large cross, but later replaced with a headstone. The headstones of those whose names were unknown are emboldened with the words "Known Unto God".[109]

The Petagas War Memorial garden is built on the site where hundreds of people, including women and children, were massacred by the Japanese.[110][111] The memorial lists 324 members of Kinabalu guerrillas of various races and ethnic groups. Other memorials such as the Kundasang War Memorial, the Last POW Camp Memorial and Quailey's Hill Memorial are dedicated to Australian and British soldiers who died in the death marches as well to honouring the sacrifices of the native population. Sandakan Memorial Park is built on the site of Sandakan Camp to honour POWs and internees. The Cho Huan Lai Memorial is dedicated to the Chinese Consulate General and several colleagues who were executed by the Japanese. The Sandakan Massacre Memorial is dedicated to 30 Chinese who were executed by the Japanese for being members of underground movements. The Sandakan War Monument is dedicated to the citizens of the town who died in the war. For bravery in fighting the Japanese in close combat Tom Starcevich was honoured with the Starcevich Monument. The Japanese also remembered, through the Jesselton Japanese Cemetery, Sandakan Japanese Cemetery and Tawau Japanese War Memorial.[112]

Australian troops inspecting the Labuan War Cemetery after its opening ceremony on 10 September 1945

Australian troops inspecting the Labuan War Cemetery after its opening ceremony on 10 September 1945

Batu Lintang Memorial

Batu Lintang Memorial

See also

Notes

- The population was made up of:

Sarawak: 580,000;

Brunei: 39,000;

North Borneo: 331,000 - Including a portion of Dutch Borneo of Pontianak and its adjacent islands

Footnotes

- 日本サラワク協会 1998.

- Kratoska 2013, p. 111.

- Vinogradov 1980, p. 73.

- Tregonning 1967, p. 216.

- Ooi 2010, p. 133.

- Braithwaite 2016, p. 253.

- Jude 2016.

- Baldacchino 2013, p. 74.

- Iriye 2014, p. 76.

- Kawamura 2000, p. 134.

- Jackson 2006, p. 438.

- Broch 1943.

- Akashi & Yoshimura 2008, p. 23.

- Ringgit 2015.

- 文原堂 1930.

- Saya & Takashi 1993, p. 54.

- Kennedy 1969, p. 344.

- Rogers 1995, p. 157.

- D. Rhodes 2001, p. 201.

- Schmidt 2005, p. 140.

- Black 2014, p. 150.

- Mendl 2001, p. 190.

- Lightner Jr. 2001, p. 30.

- Steiner 2011, p. 483.

- Dhont, Marles & Jukim 2016, p. 7.

- Ooi 2013, p. 15.

- Rottman 2013, p. 17.

- Klemen 2000.

- Chay 1988, p. 13.

- Ooi 2013, p. 1822.

- de Matos & Caprio 2015, p. 43.

- Tan 2011.

- de Matos & Caprio 2015, p. 44.

- Saunders 2013, p. 122.

- Tarling 2001, p. 193.

- The Japanese Occupation of Borneo

- Ooi 2013, p. 1823.

- Ham 2013, p. 51.

- Ooi 2010, p. 92.

- Reece 1993, p. 74.

- Felton 2009, p. 169.

- Ooi 2010, p. 101.

- Ooi 1999, p. 90.

- FitzGerald 1980, p. 88.

- Chandran 2017.

- Kratoska 2013, p. 117.

- Lebra 2010, p. 133.

- Woodward 2017, p. 38.

- Ooi 2010, p. 69.

- Fuller 1999.

- Muraoka 2016, p. 107.

- Ooi 1999, p. 125.

- Braithwaite 1989, p. 157.

- Hong 2011, p. 232.

- Ooi 2010, p. 112.

- de Matos & Caprio 2015, p. 47.

- Lee 1990, p. 17.

- Ooi 2013, p. 1782.

- Hirakawa & Shimizu 2002, p. 133.

- Ooi 2010, p. 110.

- Ooi 2013, p. 56.

- Ooi 2013, p. 29.

- Tay 2016.

- Towle, Kosuge & Kibata 2000, p. 144.

- Tregonning 1960, p. 88.

- Wall 1990, p. 61.

- Kratoska 2013, p. 125.

- Abbas & Bali 1985, p. 159.

- Luping, Chin & Dingley 1978, p. 40.

- Ooi 1999, p. 56.

- Kratoska 2013, p. 124.

- Ooi 2010, p. 186.

- Ooi 2013, p. 77.

- Kratoska 2013, p. 113.

- Jack 2001, p. 153.

- Danny 2004, p. 116.

- Feuer 2005, p. 27.

- Heimann 1998, p. 174.

- Heimann 1998, p. 218.

- Saunders 2013, p. 123.

- Johnston 2002, p. 221.

- Dod 1966, p. 636.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 252.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 253.

- Keogh 1965, p. 454.

- Johnston 2002, p. 235.

- Johnston 2002, p. 237.

- Keogh 1965, p. 455.

- Johnston 2002, p. 238.

- Labuan Corporation (1) 2017.

- Braithwaite 2016, p. 533.

- Labuan Corporation (2) 2017.

- Bullard 2006.

- Alliston 1967, p. 153.

- Ooi 2013, p. 57.

- Trefalt 2013, p. 50.

- Fitzpatrick, McCormack & Morris 2016, p. 43.

- Ooi 2013, p. 58.

- Daily Express 2014.

- Ooi 2013, p. 1852.

- Welch 2002, p. 165.

- Watt 1985, p. 210.

- Thurman & Sherman 2001, p. 123.

- The Mercury (1) 1947, p. 20.

- The Mercury (2) 1947, p. 24.

- The Argus 1947, p. 4.

- The Sydney Morning Herald 1947, p. 3.

- Welch 2002, p. 164.

- Tourism Malaysia 2010.

- Evans 1990, p. 68.

- Daily Express 2013.

- Sunami 2015, p. 13.

References

- 文原堂 (1930). 神祕境英領北ボルネオ (in Japanese). 文原堂.

- Broch, Nathan (1943). "Japanese Dreams in Borneo". The Sydney Morning Herald. Trove.

- The Mercury (1) (1947). "Four Japs General for Trial". The Mercury (Hobart). Trove.

- The Mercury (2) (1947). "Death Sentence for Japanese General". The Mercury (Hobart). Trove.

- The Argus (1947). "Jap General will die for 'death march'". The Argus (Melbourne). Trove.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (1947). "Japanese to be Hanged". The Sydney Morning Herald. Trove.

- Tregonning, K. G. (1960). North Borneo. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). The South West Pacific 1941–45. Grayflower Productions. OCLC 7185705.

- Dod, Karl C. (1966). Technical Services, Corps of Engineers, the War Against Japan. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-001879-4.

- Alliston, Cyril (1967). Threatened Paradise: North Borneo and Its Peoples. Roy Publishers.

- Kennedy, Malcolm Duncan (1969). The Estrangement of Great Britain and Japan, 1917–35. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0352-3.

- Luping, Margaret; Chin, Wen; Dingley, E. Richard (1978). Kinabalu, Summit of Borneo. Sabah Society.

- FitzGerald, Lawrence (1980). Lebanon to Labuan: a story of mapping by the Australian Survey Corps, World War II (1939 to 1945). J.G. Holmes Pty Ltd. ISBN 9780959497908.

- Vinogradov, A.G. (1980). The population of the countries of the world from most ancient times to the present days: Demography. WP IPGEB. GGKEY:CPA09LBD5WN.

- Watt, Donald Cameron (1985). The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: Index and Guide. International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-4774-0.

- Nelson, Hank (1985). P.O.W., prisoners of war: Australians under Nippon. ABC Enterprises. ISBN 978-0-642-52736-3.

- Abbas, Ismail; Bali, K. (1985). Peristiwa-peristiwa berdarah di Sabah (in Malay). Institute of Language and Literature, Ministry of Education (Malaysia).

- Chay, Peter (1988). Sabah: the land below the wind. Foto Technik. ISBN 978-967-9981-12-4.

- Braithwaite, John (1989). Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35668-8.

- Wall, Don (1990). Abandoned?: Australians at Sandakan, 1945. D. Wall. ISBN 978-0-7316-9169-2.

- Lee, Sheng-Yi (1990). The Monetary and Banking Development of Singapore and Malaysia. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-146-2.

- Evans, Stephen R. (1990). Sabah (North Borneo): Under the Rising Sun Government. Tropical Press.

- Reece, Bob (1993). Datu Bandar Abang Hj. Mustapha of Sarawak: some reflections of his life and times. Sarawak Literary Society.

- Saya, Shiraishi; Takashi, Shiraishi (1993). The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia. SEAP Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-402-5.

- Rogers, Robert F. (1995). Destiny's Landfall: A History of Guam. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1678-0.

- 日本サラワク協会 (1998). 北ボルネオサラワクと日本人: マレーシア・サラワク州と日本人の交流史 (in Japanese). せらび書房. ISBN 978-4-915961-01-4.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Heimann, Judith M. (1998). The Most Offending Soul Alive: Tom Harrisson and His Remarkable Life. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2199-9.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (1999). Rising Sun over Borneo: The Japanese Occupation of Sarawak, 1941–1945. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-27300-3.

- Fuller, Thomas (1999). "Borneo Death March /Of 2,700 Prisoners, 6 Survived : An Old Soldier Remembers a Wartime Atrocity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017.

- Klemen, L. (2000). "The Invasion of British Borneo in 1942". Dutch East Indies Webs. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017.

- Kawamura, Noriko (2000). Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-U.S. Relations During World War I. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96853-3.

- Towle, Philip; Kosuge, Margaret; Kibata, Yoichi (2000). Japanese Prisoners of War. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85285-192-7.

- D. Rhodes, Benjamin (2001). United States Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918-1941: The Golden Age of American Diplomatic and Military Complacency. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-94825-2.

- Tarling, Nicholas (2001). A Sudden Rampage: The Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia, 1941-1945. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-584-8.

- Lightner Jr., Sam (2001). All Elevations Unknown: An Adventure in the Heart of Borneo. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0-7679-0949-5.

- Mendl, Wolf (2001). Japan and South East Asia: From the Meiji Restoration to 1945. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-18205-8.

- Jack, Wong Sue (2001). Blood on Borneo. L Smith (WA) Pty, Limited. ISBN 978-0-646-41656-4.

- Thurman, Malcolm Joseph; Sherman, Christine (2001). War Crimes: Japan's World War II Atrocities. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-728-2.

- Hirakawa, Hitoshi; Shimizu, Hiroshi (2002). Japan and Singapore in the World Economy: Japan's Economic Advance into Singapore 1870-1965. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-65173-3.

- Welch, Jeanie M. (2002). The Tokyo Trial: A Bibliographic Guide to English-language Sources. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-31598-5.

- Johnston, Mark (2002). That Magnificent 9th: An illustrated history of the 9th Australian Division 1940-46. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-654-1.

- Likeman, Robert (2003). Men of the Ninth: A History of the Ninth Australian Field Ambulance 1916-1994. Slouch Hat Publications. ISBN 978-0-9579752-2-4.

- Danny, Wong Tze-Ken (2004). Historical Sabah: The Chinese. Natural History Publications (Borneo). ISBN 978-983-812-104-0.

- Feuer, A. B. (2005). Australian Commandos: Their Secret War Against the Japanese in World War II. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3294-9.

- Schmidt, Donald E. (2005). The Folly of War: American Foreign Policy, 1898-2005. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-382-5.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85285-417-1.

- Bullard, Steven (2006). "Human face of war (Post-war Rabaul)". Australian War Memorial. Australia-Japan Research Project. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017.

- Akashi, Yōji; Yoshimura, Mako (2008). New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore, 1941–1945. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-299-5.

- Heimann, Judith M. (2009). The Airmen and the Headhunters: A True Story of Lost Soldiers, Heroic Tribesmen and the Unlikeliest Rescue of World War II. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-41606-9.

- Felton, Mark (2009). Japan's Gestapo: Murder, Mayhem and Torture in Wartime Asia. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-912-3.

- Lebra, Joyce (2010). Japanese-trained Armies in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4279-44-4.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2010). The Japanese Occupation of Borneo, 1941-45. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-96309-4.

- Tourism Malaysia (2010). "Labuan War Cemetery". Tourism Malaysia. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017.

- Tan, Gabriel (2011). "Under the Nippon flag". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.

- Hong, Bi Shi (2011). "Japan's Economic Control in Southeast Asia during the Pacific War: Its Character, Effects and Legacy". School of International Studies, Yunnan University. Waseda University. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017.

- Steiner, Zara (2011). The Triumph of the Dark: European International History 1933–1939. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921200-2.

- Trefalt, Beatrice (2013). Japanese Army Stragglers and Memories of the War in Japan, 1950–75. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-38342-9.

- Baldacchino, G. (2013). The Political Economy of Divided Islands: Unified Geographies, Multiple Polities. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02313-1.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2013). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0466-2.

- Saunders, Graham (2013). A History of Brunei. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-87394-2.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2013). Post-war Borneo, 1945-50: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-05803-7.

- Ham, Paul (2013). Sandakan. Transworld. ISBN 978-1-4481-2626-2.

- Kratoska, Paul H. (2013). Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-12514-0.

- Daily Express (2013). "Granddaughter seeks apology for massacre". Daily Express. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- Iriye, Akira (2014). Japan and the Wider World: From the Mid-Nineteenth Century to the Present. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-89407-0.

- Daily Express (2014). "Looking back: North Borneo war scars". Daily Express. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- Black, Jeremy (2014). Introduction to Global Military History: 1775 to the Present Day. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79640-4.

- de Matos, Christine; Caprio, M. (2015). Japan as the Occupier and the Occupied. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-40811-2.

- Ringgit, Danielle Sendou (2015). "Sarawak and the Japanese occupation". The Borneo Post Seeds. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017.

- Wiesman, Hans (2015). The Dakota Hunter: In Search of the Legendary DC-3 on the Last Frontiers. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-61200-259-0.

- Sunami, Sōichirō (2015). アジアにおける日本人墓標の諸相 --その記録と研究史-- [Aspects of Japanese Headstones on the Asian Continent : Records and Research History] (PDF). The Zinbun Gakuhō : Journal of Humanities (in Japanese). doi:10.14989/204513. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2019 – via Kyoto University Research Information Repository.

- Tay, Frances (2016). "Japanese War Crimes in British Malaya and British Borneo 1941–1945". Japanese War Crimes Malaya Borneo. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017.

- Dhont, Frank; Marles, Janet E.; Jukim, Maslin (2016). "Memories of World War II: Oral History of Brunei Darussalam (Dec. 1941 – June 1942)" (PDF). Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Institute of Asian Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2017.

- Fitzpatrick, Georgina; McCormack, Timothy L.H.; Morris, Narrelle (2016). Australia's War Crimes Trials 1945–51. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-29205-5.

- Jude, Marcel (2016). "Japanese community in North Borneo long before World War II". The Borneo Post. PressReader.

- Braithwaite, Richard Wallace (2016). Fighting Monsters: An Intimate History of the Sandakan Tragedy. Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925333-76-3.

- Muraoka, Takamitsu (2016). My Via Dolorosa: Along the Trails of the Japanese Imperialism in Asia. AuthorHouse UK. ISBN 978-1-5246-2871-0.

- Woodward, C. Vann (2017). The Battle for Leyte Gulf: The Incredible Story of World War II's Largest Naval Battle. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5107-2135-7.

- Chandran, Esther (2017). "Discovering Labuan and loving it". The Star. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017.

- Welman, Frans (2017). Borneo Trilogy Volume 1: Sabah. Booksmango. ISBN 978-616-245-078-5.

- Labuan Corporation (1) (2017). "Peace Park (Taman Damai)". Labuan Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017.

- Labuan Corporation (2) (2017). "Surrender Point". Labuan Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017.

- Tanaka, Yuki (2017). Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5381-0270-1.

External links

![]() Media related to Japanese occupation of British Borneo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Japanese occupation of British Borneo at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)

.JPG.webp)