Aden

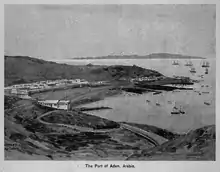

Aden (UK: /ˈeɪdən/ AY-dən, US: /ˈɑːdɛn/ AH-den; Arabic: عدن ʿAdin/ʿAdan Yemeni: [ˈʕæden, ˈʕædæn]) is a city, since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some 170 km (110 mi) east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. Aden's natural harbour lies in the crater of a dormant volcano, which now forms a peninsula joined to the mainland by a low isthmus. This harbour, Front Bay, was first used by the ancient Kingdom of Awsan between the 5th and 7th centuries BC. The modern harbour is on the other side of the peninsula. Aden gives its name to the Gulf of Aden.

Aden

عدن | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)    .jpg.webp) Clockwise from top: Steamer point, Mosque and the old town, St.Francis of Assisi Church, Cisterns of Tawila, Old Town streetview | |

Aden Location in Yemen | |

| Coordinates: 12°48′N 45°02′E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aden |

| Control | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 760 km2 (290 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 6 m (20 ft) |

| Population (2017[1]) | |

| • Total | 863,000 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Area code(s) | 967 |

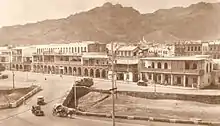

Aden consists of a number of distinct sub-centres: Crater, the original port city; Ma'alla, the modern port; Tawahi, known as "Steamer Point" in the colonial period; and the resorts of Gold Mohur. Khormaksar, on the isthmus that connects Aden proper with the mainland, includes the city's diplomatic missions, the main offices of Aden University, and Aden International Airport (the former British Royal Air Force station RAF Khormaksar), Yemen's second biggest airport. On the mainland are the sub-centres of Sheikh Othman, a former oasis area; Al-Mansura, a town planned by the British; and Madinat ash-Sha'b (formerly Madinat al-Itihad), the site designated as the capital of the South Arabian Federation and now home to a large power/desalinization facility and additional faculties of Aden University.

Aden encloses the eastern side of a vast, natural harbour that comprises the modern port. This city is rather large, yet has no natural resources available in it. However, Aden does have reservoirs, the Aden Tanks. These reservoirs accumulate rain water for the sole purpose of drinking for the city's citizens. The city is prosperous with rich merchants living here and Indian vessels arriving for trade.[2] The volcanic peninsula of Little Aden forms a near-mirror image, enclosing the harbour and port on the western side. Little Aden became the site of the oil refinery and tanker port. Both were established and operated by British Petroleum until they were turned over to Yemeni government ownership and control in 1978.

Aden was the capital of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen until that country's unification with the Yemen Arab Republic in 1990, and again briefly served as Yemen's temporary capital during the aftermath of the Houthi takeover in Yemen, as declared by President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi after he fled the Houthi occupation of Sana'a.[3] From March to July 2015, the Battle of Aden raged between Houthis and government forces of President Hadi. Water, food, and medical supplies ran short in the city.[4] On 14 July, the Saudi Army launched an offensive to retake Aden for the Yemeni government. Within three days the Houthis had been removed from the city.[5] Since February 2018, Aden has been seized by the Southern Transitional Council, that is supported by UAE, the Southern Transitional Council was formed from previous Aden Mayor Aidroos Alzubaidi after he was dismissed from his post by Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi together with sacked former Cabinet minister Salfi-religious leader Hani Bin Buraik.

History

Antiquity

A local legend in Yemen states that Aden may be as old as human history itself. Some also believe that Cain and Abel are buried somewhere in the city.[6]

The port's convenient position on the sea route between India and Europe has made Aden desirable to rulers who sought to possess it at various times throughout history. Known as Eudaemon (Ancient Greek: Ευδαίμων, meaning "blissful, prosperous,") in the 1st century BC, it was a transshipping point for the Red Sea trade, but fell on hard times when new shipping practices by-passed it and made the daring direct crossing to India in the 1st century AD, according to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. The same work describes Aden as "a village by the shore," which would well describe the town of Crater while it was still little-developed. There is no mention of fortification at this stage, Aden was more an island than a peninsula as the isthmus (a tombolo) was not then so developed as it is today.

Medieval

Although the pre-Islamic Himyar civilization was capable of building large structures, there seems to have been little fortification at this stage. Fortifications at Mareb and other places in Yemen and the Hadhramaut make it clear that both the Himyar and the Sabean cultures were well capable of it. Thus, watch towers, since destroyed, are possible. However, the Arab historians Ibn al Mojawir and Abu Makhramah attribute the first fortification of Aden to Beni Zuree'a. Abu Makhramah has also included a detailed biography of Muhammad Azim Sultan Qamarbandi Naqsh in his work, Tarikh ul-Yemen. The aim seems to have been twofold: to keep hostile forces out and to maintain revenue by controlling the movement of goods, thereby preventing smuggling. In its original form, some of this work was relatively feeble.

After 1175 AD, rebuilding in a more solid form began, and ever since Aden became a popular city attracting sailors and merchants from Egypt, Sindh, Gujarat, East Africa and even China. According to Muqaddasi, Persians formed the majority of Aden's population in the 10th century.[7][8]

In 1421, China's Ming dynasty Yongle Emperor ordered principal envoy grand eunuch Li Xing and grand eunuch Zhou Man of Zheng He's fleet to convey an imperial edict with hats and robes to bestow on the king of Aden. The envoys boarded three treasure ships and set sail from Sumatra to the port of Aden. This event was recorded in the book Yingyai Shenglan by Ma Huan who accompanied the imperial envoy.[9]

In 1513, the Portuguese, led by Afonso de Albuquerque, launched an unsuccessful four-day naval siege of Aden.[10]

British administration 1839–1967

.jpg.webp)

Before British administration, Aden was ruled by the Portuguese between 1513 and 1538 and 1547–1548. It was ruled by the Ottoman Empire between 1538 and 1547 and between 1548 and 1645.

In 1609 The Ascension was the first English ship to visit Aden, before sailing on to Mocha during the fourth voyage of the East India Company.[12]

After Ottoman rule, Aden was ruled by the Sultanate of Lahej, under suzerainty of the Zaidi imams of Yemen.

British interests in Aden began in 1796 with Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, after which a British fleet docked at Aden for several months at the invitation of the sultan. The French were defeated in Egypt in 1801, and their privateers were tracked down over the subsequent decade. By 1800, Aden was a small village with a population of 600 Arabs, Somalis, Jews, and Indians—housed for the most part in huts of reed matting erected among ruins recalling a vanished era of wealth and prosperity. As there was little British trade in the Red Sea, most British politicians until the 1830s had no further interest in the area beyond the suppression of piracy. However, a small number of government officials and the East India Company officials thought that a British base in the area was necessary to prevent another French advance through Egypt or Russian expansion through Persia. The emergence of Muhammad Ali of Egypt as a strong local ruler only increased their concerns. The governor of Bombay from 1834 to 1838, Sir Robert Grant, was one of those who believed that India could only be protected by pre-emptively seizing 'places of strength' to protect the Indian Ocean.

The Red Sea increased in importance after the steamship Hugh Lindsay sailed from Bombay to the Suez isthmus in 1830, stopping at Aden with the sultan's consent to resupply with coal. Although cargo was still carried around the Cape of Good Hope in sailing ships, a steam route to the Suez could provide a much quicker option for transporting officials and important communications. Grant felt that armed ships steaming regularly between Bombay and Suez would help secure British interests in the region and did all he could to progress his vision. After lengthy negotiations due to the costs of investing in the new technology, the government agreed to pay half the costs for six voyages per year and the East India Company board approved the purchase of two new steamers in 1837. Grant immediately announced that monthly voyages to Suez would take place, despite the fact that no secure coaling station had been found.[13]

In 1838, under Muhsin bin Fadl, Lahej ceded 194 km2 (75 sq mi) including Aden to the British. On 19 January 1839, the British East India Company landed Royal Marines at Aden to secure the territory and stop attacks by pirates against British shipping to India. In 1850 it was declared a free trade port, with the liquor, salt, arms, and opium trades developing duties as it won all the coffee trade from Mokha.[14] The port lies about equidistant from the Suez Canal, Mumbai, and Zanzibar, which were all important British possessions. Aden had been an entrepôt and a way-station for seamen in the ancient world. There, supplies, particularly water, were replenished, so, in the mid-19th century, it became necessary to replenish coal and boiler water. Thus Aden acquired a coaling station at Steamer Point and Aden was to remain under British control until November 1967.

Until 1937, Aden was governed as part of British India and was known as the Aden Settlement. Its original territory was enlarged in 1857 by the 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi) island of Perim, in 1868 by the 73 km2 (28 sq mi) Khuriya Muriya Islands, and in 1915 by the 108 km2 (42 sq mi) island of Kamaran. The settlement would become Aden Province in 1935.

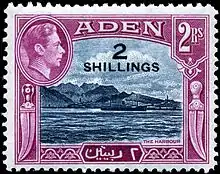

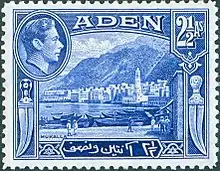

In 1937, the settlement was detached from India and became the Colony of Aden, a British Crown colony. The change in government was a step towards the change in monetary units seen in the stamps illustrating this article. When British India became independent in 1947, Indian rupees (divided into annas) were replaced in Aden by East African shillings. The hinterland of Aden and Hadhramaut were also loosely tied to Britain as the Aden Protectorate, which was overseen from Aden.

Aden's location also made it a useful entrepôt for mail passing between places around the Indian Ocean and Europe. Thus, a ship passing from Suez to Bombay could leave mail for Mombasa at Aden for collection. See Postage stamps and postal history of Aden.

The 1947 Aden riots saw more than 80 Jews killed, their property looted and schools burned by a Muslim mob. After the Suez Crisis in 1956, Aden became the main location in the region for the British.

Aden sent a team of two to the 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Perth, Western Australia.

Little Aden 1955 to 1967

Little Aden is still dominated by the oil refinery built for British Petroleum. Little Aden was well known to seafarers for its tanker port with a very welcoming seaman's mission near to the BP Aden tugs' jetties, complete with swimming pool and air conditioned bar. The accommodation areas for the refinery personnel were known by the original Arabic names of Bureika and Ghadir.

Bureika was wooden housing bunkhouses built to accommodate the thousands of skilled men and laborers imported to build the refinery, later converted to family housing, plus imported prefabricated houses "the Riley-Newsums" that are also to be found in parts of Australia (Woomera). Bureika also had a protected bathing area and Beach Club.

Ghadir housing was stone built, largely from the local granite quarry; much of this housing still stands today, now occupied by wealthier locals from Aden. Little Aden also has a local township and numerous picturesque fishing villages, including the Lobster Pots of Ghadir. The British Army had extensive camps in Bureika and through Silent Valley in Falaise Camp, these successfully protected the refinery staff and facilities throughout the troubles, with only a very few exceptions. Schooling was provided for children from kindergarten age through to primary school, after that, children were bussed to The Isthmus School in Khormaksar, though this had to be stopped during the Aden Emergency.

Federation of South Arabia and the Aden Emergency

In order to stabilize Aden and the surrounding Aden Protectorate from the designs of the Egyptian backed republicans of North Yemen, the British attempted to gradually unite the disparate states of the region in preparation for eventual independence. On 18 January 1963, the Colony of Aden was incorporated into the Federation of Arab Emirates of the South against the wishes of North Yemen. The city became the State of Aden and the Federation was renamed the Federation of South Arabia (FSA).

An insurgency against British administration known as the Aden Emergency began with a grenade attack by the communist National Liberation Front (NLF), against the British High Commissioner on 10 December 1963, killing one person and injuring fifty, and a "state of emergency" was declared.

In 1964, Britain announced its intention to grant independence to the FSA in 1968, but that the British military would remain in Aden. The security situation deteriorated as NLF and FLOSY (Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen) vied for the upper hand.

In January 1967, there were mass riots between the NLF and their rival FLOSY supporters in the old Arab quarter of Aden town. This conflict continued until mid February, despite the intervention of British troops. On 20 June 1967, 23 British Army officers were ambushed and shot dead by members of Aden Police during the Aden Mutiny in the Crater District. During the period there were as many attacks on the British troops by both sides as against each other culminating in the destruction of an Aden Airways DC3 plane in the air with no survivors.

The increased violence was a determining factor in the British ensuring all families were evacuated more quickly than initially intended, as recorded in From Barren Rocks to Living Stones.

On 30 November 1967 British troops were evacuated, leaving Aden and the rest of the FSA under NLF control. The Royal Marines, who had been the first British troops to arrive in Aden in 1839, were the last to leave – with the exception of a Royal Engineer detachment (10 Airfields Squadron left Aden on 13 December 1967).

Independence

Aden ceased to be a Colony of the United Kingdom and became the capital of a new state known as the People's Republic of South Yemen which, in 1970, was renamed the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen. With the unification of northern and southern Yemen in 1990, Aden was no longer a national capital but remained the capital of Aden Governorate which covered an area similar to that of the Aden Colony.

On 29 December 1992, Al Qaeda conducted its first known terrorist attack in Aden, bombing the Gold Mohur Hotel, where US servicemen were known to have been staying en route to Somalia for Operation Restore Hope. A Yemeni and an Austrian tourist died in the attack.[15]

Aden was briefly the centre of the secessionist Democratic Republic of Yemen from 21 May 1994 but was reunited by Republic of Yemen troops on 7 July 1994.

Members of al Qaeda attempted to bomb the US guided-missile destroyer The Sullivans at the port of Aden as part of the 2000 millennium attack plots. The boat that had the explosives in it sank, forcing the planned attack to be aborted.

The bombing attack on destroyer USS Cole took place in Aden on 12 October 2000.

In 2007 growing dissatisfaction with unification led to the formation of the secessionist South Yemen Movement. According to The New York Times, the Movement's mainly underground leadership includes socialists, Islamists and individuals desiring a return to the perceived benefits of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen.[16]

President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi fled to Aden, his hometown, in 2015 after being deposed in a coup d'état. He declared that he was still Yemen's legitimate president and called on state institutions and loyal officials to relocate to Aden.[17] In a televised speech on 21 March 2015, he declared Aden to be Yemen's "economic and temporary capital" while Sana'a is controlled by the Houthis.[3]

Aden was hit by violence in the aftermath of the coup d'état, with forces loyal to Hadi clashing with those loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh in a battle for Aden International Airport on 19 March 2015.[18] After the airport battle, the entire city became a battleground for the Battle of Aden, which left large parts of the city in ruins and has killed at least 198 people since March 25, 2015.[4] On 14 July 2015, the Saudi Arabian Army launched an offensive to win control of the city. Within three days, the city was cleared of Houthi rebels, ending the Battle of Aden with a coalition victory.[5]

Beginning on 28 January 2018, separatists loyal to the STC seized control of the Yemeni government headquarters in Aden in a coup d'état against the Hadi-led government.[19][20]

President of the STC Aidarus al-Zoubaidi announced the state of emergency in Aden and that "the STC has begun the process of overthrowing Hadi's rule over the South".[21]

On 1 August 2019, General Munir Al Yafi the serving commander of the STC was killed in a Houthi-missile strike alongside dozens of Yemeni soldiers in a military camp in western Aden.[22]

Main sites

Aden has a number of historical and natural sites of interest to visitors. These include:

- The historical British churches, one of which lies empty and semi-derelict in 2019.[23]

- The Zoroastrian Temple

- The Cisterns of Tawila—an ancient water-catchment system located in the sub-centre of Crater

- Sira Fort

- The Aden Minaret[24]

- Little Ben, a miniature Big Ben Clock Tower overlooking Steamer Point. Built during the colonial period, this was restored in 2012 after 3 decades of neglect since the British withdrawal of 1967.

- The Landing Pier at Steamer Point is a 19th-century building used by visiting dignitaries during the colonial period, most notably Queen Elizabeth during her 1954 visit to the colony. This building was hit by an airstrike in 2015 and is currently in the process of being restored in 2019.

- The Crescent Hotel which contained a number of artifacts relating to the Royal Visit of 1954 and which currently remains derelict as a result of a recent airstrike.

- The Palace of the Sultanate of Lahej/National Museum—The National Museum was founded in 1966 and is located in what used to be the Palace of the Sultanate of Lehej. Northern forces robbed it during the 1994 Civil War, but its collection of pieces remains one of the biggest in Yemen.[25][26]

- The Aden Military Museum which features a painting depicting 20 June 1967 ambush by Arab Police Barracks on a British Army unit when a number of the 22 officers killed that day were driving in 2 Landrovers on Queen Arwa Road, Crater.

- The Rimbaud House, which opened in 1991, is the two-story house of French poet Arthur Rimbaud who lived in Aden from 1880 to 1891. Rimbaud moved to Aden on his way to Ethiopia in an attempt for a new life. As of the late 1990s, the first floor of the house belonged to the French Consulate, a cultural centre and a library. The house is located in al-Tawahi—the European Quarter of Aden—and is politically and culturally debated for its French nature in an area previously colonized by Britain.[27]

- The fortifications of Jebal Hadid and Jebal Shamsan

- The beaches of Aden and Little Aden—Some of the popular beaches in Aden consist of Lover's Bay Beach, Elephant Beach and Gold Beach. The popular beach in Little Aden is called Blue Beach.[25] Some beaches are private and some are public, which is subject to change over time due to the changing resort industry. According to the Wall Street Journal, kidnappings on the beaches and the threat of Al Qaeda has caused problems for the resort industry in Aden, which used to be popular among locals and Westerners.[28]

- Al-Aidaroos Mosque[24]

- Main Pass – now called Al-Aqba Road is the only road into Aden through Crater. Originally an Arched Upper bridge known as Main Gate, it overlooked Aden city and was built during the Ottoman Empire. A painted crest of the 24th British army battalion is still visible on the brickwork adjacent to the Gate site and is believed to be the only remaining army Crest from colonial rule still visible in Aden. In March 1963 the bridge was removed by a British Army controlled explosion to widen the 2 lane roadway to the present 4 lane highway and the only reminder of this bridge is a quarter scale replica built at the end of the Al-Aqba road intersection known as the AdenGate Model roundabout.

Economy

Historically, Aden would import goods from the African coast and from Europe, the United States, and India.[29][30] As of 1920, the British described it as "the chief emporium of Arabian trade, receiving the small quantities of native produce, and supplying the modest wants of the interior and of most of the smaller Arabian ports." At the docks, the city provided coal to passing ships. The only item being produced by the city, as of 1920, was salt.[30] Also, the port was the stop ships had to take when entering the Bab-el-Mandeb; this was how cities like Mecca had received goods by ship. Yemen Airlines, the national airline of South Yemen, had its head office in Aden. On 15 May 1996, Yemen Airlines merged with Yemenia.[31][32]

During the early 20th century Aden was a notable centre of coffee production. Women processed coffee beans, grown in the Yemen highlands.[33] Frankincense, wheat, barley, alfalfa, and millet was also produced and exported from Aden.[34][35] The leaves and stalks of the alfalfa, millet and maize produced in Aden were generally used as fodder.[35] As of 1920, Aden was also gathering salt from salt water. An Italian company called Agostino Burgarella Ajola and Company gathered and process the salt under the name Aden Salt Works. There was also a smaller company from India, called Abdullabhoy and Joomabhoy Lalji & Company that owned a salt production firm in Aden. Both companies exported the salt. Between 1916 and 1917, Aden produced over 120,000 tons of salt. Aden has also produced potash, which was generally exported to Mumbai.[36]

Aden produced jollyboats. Charcoal was produced as well, from acacia, and mainly in the interior of the region. Cigarettes were produced by Jewish and Greek populations in Aden. The tobacco used was imported from Egypt.[37]

Transportation

Historically, Aden's harbour has been a major hub of transportation for the region. As of 1920, the harbour was 13 by 6 km (8 by 4 mi) in size. Passenger ships landed at Steamer Point now called Tawahi.[29]

During the British colonial period motor vehicles drove on the left, as in the United Kingdom. On 2 January 1977, Aden, along with the rest of South Yemen, changed to driving on the right, bringing it into line with neighbouring Arab states.[38]

The city was served by Aden International Airport, the former RAF Khormaksar station which is 10 km (6.2 mi) away from the city, before the Battle of Aden Airport and the 2015 military intervention in Yemen closed this airport along with other airports in Yemen. On July 22, Aden International Airport was declared fit for operation again after the Houthi forces were driven from the city, and a Saudi plane carrying aid reportedly became the first plane to land in Aden in four months.[39] The same day, a ship chartered by the World Food Programme carrying fuel docked in Aden's port.[40]

Climate

Aden has a hot desert climate (BWh) in the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system. Although Aden sees next to no precipitation year-round, it is humid throughout the year.

| Climate data for Aden | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.1 (88.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

42.8 (109.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

42.8 (109.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.5 (83.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

36.6 (97.9) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.4 (95.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.7 (78.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.1 (84.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 6 (0.2) |

3 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

2 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

1 (0.0) |

3 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

36 (1.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 20 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 72 | 74 | 74 | 72 | 66 | 65 | 65 | 69 | 68 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 241.8 | 203.4 | 217.0 | 240.0 | 303.8 | 282.0 | 241.8 | 269.7 | 270.0 | 294.5 | 285.0 | 257.3 | 3,106.3 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.8 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 8.5 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[41] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C (77 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 30 °C (86 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 30 °C (86 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) |

See also

Footnotes

- Central Statistical Organisation. "Yemen Statistical Yearbook for 2017". Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 87, 307. ISBN 9780330418799.

- "Yemen's President Hadi declares new 'temporary capital'". Deutsche Welle. 21 March 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Fahim, Karim; Bin Lazrq, Fathi (10 April 2015). "Yemen's Despair on Full Display in 'Ruined' City". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "Proxies and paranoia". The Economist. Economist Group. The Economist. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Modern Middle East Nations and Their Strategic Place in the World: Yemen, 2004, by Hal Markovitz. ISBN 1-59084-521-8

- Lawrence G. Potter (2009). The Persian Gulf in History. p. 180. ISBN 9780230618459.

- Dr Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh (2013). Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography. p. 64. ISBN 9781136817175.

- Ma Huan Ying-yai Sheng-lan, The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores, 1433, translated by J.V.G. Mills, with foreword and preface, Hakluty Society, London 1970; reprinted by the White Lotus Press 1997. ISBN 974-8496-78-3

- Broeze (28 October 2013). Gateways Of Asia. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-136-16895-6.

- Port of Aden inner harbour

- J. K. Laughton, ‘Jourdain, John (c.1572–1619)’, rev. H. V. Bowen, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008

- Christie, Nikki (2016). Gaining and Losing an Empire: Britain 1763–1916. Pearson. pp. 53–55.

- Great Britain Hydrographic Dept (1900). The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Pilot (5th ed.). Order of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. p. 348.

- "Timeline: Al Qaeda's Global Context: Al Qaeda's First Attack". Frontline: The Man Who Knew. pbs.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Worth, Robert F. (28 February 2010). "In Yemen's South, Protests Could Cause More Instability". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- "Head of GCC visits embattled Hadi in Aden". The Daily Star. 26 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Hendawi, Hamza (20 March 2015). "Fierce gun battle between factions at Yemen airport". The Scotsman. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- "Separatist clashes flare in south Yemen". BBC News. 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Yémen: les séparatistes sudistes, à la recherche de l'indépendance perdue". Le Point. 28 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "South Yemen separatists send reinforcements to Aden". Almasdarnews.com. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "All You Need To Know About The Killed Separatist Leader "Abu Al-Yamamah"". adennews. 13 July 2020.

- Jamal, Shafee (2012-01-12). "Aden's rich religious heritage." Yemen Times (YemenTimes.com). Archived 2015-05-04.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- McLaughlin, Daniel (2008). Yemen. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 183.

- "Arabia Antica: Pre-islamic Arabia, Culture and Archaeology: About". arabiantica.humnet.unipi.it. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Taminian, Lucine (1998). "Rimbaud's House in Aden, Yemen: Giving Voice(s) to the Silent Poet". Cultural Anthropology. 13 (4): 464–490. doi:10.1525/can.1998.13.4.464. JSTOR 656569.

- Abi Habib, Maria (6 June 2013). "Aden, Once The Lively Beach Resort of Yemen, Struggles Under Sway of Al Qaeda". The Wall Street Journal.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 68.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 69.

- "North and South Yemen Airlines to Merge". Flight International. 10–16 April 1996. 10.

- "Yemenia background Archived 2009-10-27 at the Wayback Machine". Yemenia. Retrieved on 26 October 2009.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 83.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 84.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 86.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 98.

- Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 99.

- The Rule of the Road: An International Guide to History and Practice, Peter Kincaid, Greenwood Press, 1986, page 200

- "Aden Airport ready to operate". Yemen Times. 22 July 2015. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "New WFP Ship Arrives in Aden Port With Fuel For Humanitarian Operations". World Food Programme. United Nations. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Klimatafel von Aden-Chormaksar / Jemen" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

References

- Garston, J. "Aden: The First Hundred Years," History Today (March 1965) 15#3 pp 147–158. covers 1839 to 1939.

- Norris, H.T.; Penhey, F.W. (1955). "The Historical Development of Aden's defences". The Geographical Journal. CXXI part I.

Further reading

- Khalili, Laleh (2020). Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula. London: Verso Books. ISBN 9781786634818. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aden. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Aden. |

Aden travel guide from Wikivoyage

Aden travel guide from Wikivoyage- ArchNet.org. "Aden". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007.