Imperial Brazilian Navy

The Imperial Brazilian Navy (Portuguese: Armada Nacional, commonly known as Armada Imperial) was the navy created at the time of the independence of the Empire of Brazil from the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. It existed between 1822 and 1889 during the vacancy of the constitutional monarchy. The Navy was formed almost entirely by ships, staff, organizations and doctrines proceeding from the transference of the Portuguese Royal Family in 1808. Some of its members were native-born Brazilians, who under Portugal had been forbidden to serve. Other members were Portuguese who adhered to the cause of separation and German and Irish mercenaries. Some establishments created by King João VI were used and incorporated. Under the reign of Emperor Pedro II the Navy was greatly expanded to become the fifth most powerful navy in the world and the armed force more popular and loyal to the Brazilian monarchy. The republican coup d'état in 1889, led by army men, put an end to the Imperial Navy that fell into decay until the new century.

| Imperial Brazilian Navy Armada Nacional | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Flag of the Empire of Brazil | |

| Active | 1822–1889 |

| Country | |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Protecting the Empire of Brazil and its interests by using naval forces. |

| Engagements | War of Independence of Brazil Confederation of the Equator Cisplatine War Ragamuffin War Cabanagem Revolt Sabinada Revolt Balaiada Revolt Platine War Uruguayan War Paraguayan War |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Notable commanders | Marquis of Tamandaré Baron of Amazonas Thomas Cochrane John Pascoe Grenfell Viscount of Inhaúma |

| Insignia | |

| Navy Ensign | .svg.png.webp) |

| Naval Jack |  |

Creation

The Imperial Navy came into being with the independence of the country in 1822 to fight and to expel the Portuguese troops dispersed by the territory. The transfer of the Portuguese monarchy to Brazil in 1808 during the Napoleonic wars resulted in the transfer of a large part of the structure, personnel and ships of the Portuguese Navy. These became the core of the recently created Imperial Navy. A number of establishments previously created by King John were incorporated into the navy such as the Department of Navy, Headquarters of the Navy, the Intendancy and Accounting Department, the Arsenal (Shipyard) of the Navy, the Academy of Navy Guards, the Naval Hospital, the Auditorship, the Supreme Military Council, the powder plant, and others. Due to the necessity of the war, its initial contingent was formed by Brazilians, Portuguese who joined the independence and mainly by foreign mercenaries. The Brazilian-born Captain Luís da Cunha Moreira was chosen as the first minister of the Navy on 28 October 1822.[1][2]

Structure

Under Articles 102 and 148 of the Constitution, the Brazilian Armed Forces were subordinate to the Emperor as Commander-in-Chief.[3] He was aided by the Ministers of War and Navy in matters concerning the Army and the Navy—although the Prime Minister usually exercised oversight of both branches in practice. The ministers of War and Navy were, with few exceptions, civilians.[4][5] The model chosen was the British parliamentary or Anglo-American system, in which "the country's Armed Forces observed unrestricted obedience to the civilian government while maintaining distance from political decisions and decisions referring to borders' security".[6]

Brazil's first line of defense relied upon a large and powerful navy to protect against foreign attack. The military was organized along similar lines to the British and American armed forces of the time. As a matter of policy, the military was to be completely obedient to civilian governmental control and to remain at arm's length from involvement in political decisions. Military personnel were allowed to run for and serve in political office while remaining on active duty. However they did not represent the Army or the Navy, but were instead expected to serve the interests of the city or province which had elected them.[7]

First Reign, 1822-1831

British naval officer Lord Thomas Alexander Cochrane was made the commander of the Imperial Navy and received the rank of "First Admiral".[8][9] At that time, the fleet was composed of one ship of the line, four frigates, and smaller ships for a total of 38 warships. The Secretary of Treasury Martim Francisco Ribeiro de Andrada created a national subscription to generate capital in order to increase the size of the fleet. Contributions were sent from all over Brazil. Even the Emperor Pedro I acquired a merchant brig at his own expense (that was renamed "Caboclo") and donated it to the State.[9][10] The navy fought in the north and also south of Brazil where it had a decisive role in the independence of the country.[11]

After the suppression of the revolt in Pernambuco in 1824 and prior to the Cisplatine War, the navy increased significantly in size and strength. Starting with 38 ships in 1822, eventually the navy had 96 modern warships of various types with over 690 cannons. The Navy blocked the estuary of the Rio de la Plata hindering the contact of the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata (as Argentina was then called) with the Cisplatine rebels and the outside world. Several battles had occurred between Brazilian and Argentine ships until the defeat of an Argentine flotilla composed of two corvettes, five brigs and one barquentine near the Island of Santiago in 1827. When Pedro I abdicated in 1831, he left a powerful navy made up of two ships of the line and ten frigates in addition to corvettes, steamships, and other ships for a total of at least 80 warships in peacetime.[12][13]

War of the Independence

The action of the navy was essential during the war of independence to avoid the arrival of new Portuguese troops in Brazilian territory. Both parties (Portuguese and Brazilian) saw the Portuguese warships spread across the country (mostly in poor condition) as the instrument through which military victory could be achieved. In early 1822, the Portuguese navy controlled a ship of the line, two frigates, four corvettes, two brigs, and four warships of other categories in Brazilian waters.

Warships available immediately for the new Brazilian navy were numerous, but in disrepair. The hulls of several ships that were brought by the Royal Family and the Court to be abandoned in Brazil were rotten and therefore of little value. The Brazilian agent in London, Marquis of Batley (Philibert Marshal Brant) received orders to acquire warships fully equipped and manned on credit. No vendor, however, was willing to take the risks. Finally, there was an initial public offering, and the new Emperor personally signed for 350 of them, inspiring others to do the same. Thus, the new government was successful in raising funds to purchase a fleet.

Arranging crews was another problem. A significant number of former officers and Portuguese sailors volunteered to serve the new nation, and swore loyalty to it. Their loyalty, however, was under suspicion. For this reason, British officers and men were recruited to fill out the ranks and end the dependence on the Portuguese.

Brazilian Navy was led by British officer Thomas Cochrane. The newly renovated navy experienced a number of early setbacks due to sabotage by Portuguese-born men in the naval crews. But by 1823 the navy had been reformed and the Portuguese members were replaced by native Brazilians, freed slaves, pardoned prisoners as well as more experienced British and American mercenaries. Navy succeeded in clearing the coast of the Portuguese presence and isolating the remaining Portuguese land troops. By the end of 1823, the Brazilian naval forces had pursued the remaining Portuguese ships across the Atlantic nearly as far as the shores of Portugal.

Cisplatine War

The Cisplatine War was a war between the Empire of Brazil and the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata for control of the current territory of Uruguay. Rebels led by Fructuoso Rivera and Juan Antonio Lavalleja carried on resistance against Brazilian rule. In 1825, a Congress of delegates from all over the Eastern Bank met in La Florida and declared independence from Brazil, while reaffirming its allegiance to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. In response, Brazil declared war on the United Provinces.

Brazilian Emperor Pedro I ordered his fleet to block the River Plate and its two main ports, Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The Argentina fleet moved south, first to Ensenada and then to distant Carmen de Patagones on the Atlantic Ocean. The Brazilian fleet attempted to take Carmen de Patagones in 1827 and thus tighten its blockade over Argentina, but Brazilian troops were eventually repelled by local civilians. Despite a big battle, a series of smaller clashes ensued, including the naval Battles of Juncal and Monte Santiago.

Regencial Period, 1831-1840

During the disturbed years of regency, the Arsenal, Navy department, and the Naval Jail were improved and the Imperial Mariner Corps (formed then by volunteers) was created. Steam navigation was definitively adopted in the 1830s. The Navy also successfully fought against all revolts that occurred during the Regency (where it made blockades and transported the Army troops) including: Cabanagem, Ragamuffin War, Sabinada, Balaiada, amongst others.[13][14]

When Emperor Pedro II was declared of legal age and assumed his constitutional prerogatives in 1840, the Armada had over 90 warships: six frigates, seven corvettes, two barque-schooners, six brigs, eight brig-schooners, 16 gunboats, 12 schooners, seven armed brigantine-schooners, six steam barques, three transport ships, two armed luggers, two cutters and thirteen larger boats.

Second Reign, 1831-1889

During the 58-year reign of Pedro II the Brazilian Navy achieved its greatest strength in relation to navies around the world.[15] several establishments were improved and created. Steam navigation, ironclad armour and torpedoes was adopted. Brazil quickly modernized the fleet acquiring ships from foreign sources while also constructing others locally. Brazil's Navy substituted the old smoothbore cannons for new ones with rifled barrels, which were more accurate and had longer ranges. Improvements were also made in the Arsenals (shipyards) and naval bases, which were equipped with new workshops. Ships were constructed in the Arsenal of the Navy in Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Recife, Santos, Niterói and Pelotas. All revolts were suppressed.

During the 1850s the State Secretary, the Accounting Department of the Navy, the Headquarters of the Navy and the Naval Academy were reorganized and improved. New ships were purchased and the ports administrations were better equipped. The Imperial Mariner Corps was definitively regularized and the Marine Corps was created, taking the place of the Naval Artillery. The Service of Assistance for Invalids was also established, along with several schools for sailors and craftsmen.[16]

Platine Wars

The conflicts in the Platine region did not cease after the war of 1825. The anarchy caused by the despotic Rosas and his desire to subdue Bolívia, Uruguay and Paraguay forced Brazil to intercede, in the Platine War. The Imperial Government sent a naval force of 17 warships (a ship of the line, 10 corvettes and six steamships) commanded by the veteran John Pascoe Grenfell. The Brazilian fleet succeeded in passing through the Argentine line of defence at the Tonelero Pass under heavy attack and transported the troops to the theater of operations. The Imperial Navy had a total of 59 vessels of various types in 1851: 36 armed sailing ships, 10 armed steamships, seven unarmed sailing ships and six sailing transports.[17] Victorious in an international war, the Imperial Navy consolidated like naval power of South America guaranteeing the hegemony to Brazil in the Rio de La Plata.

| Year | Navy (number of ships) |

|---|---|

| 1822 | 38 |

| 1825 | 96 |

| 1831 | 80 |

| 1840 | 90 |

| 1851 | 59 |

| 1864 | 40 |

| 1870 | 94 |

| 1889 | 60 |

More than a decade later the Navy was once again modernized and its fleet of old sailing ships was converted to a fleet of 40 steamships armed with more than 250 cannons.[18] In 1864 the navy fought in the Uruguayan War and immediately afterwards in the Paraguayan War where it annihilated the Paraguayan Navy in the Battle of Riachuelo, the biggest naval battle of the Latin America. The navy was further augmented with the acquisition of 20 ironclads and six fluvial monitors. At least 9,177 navy personnel fought in the five years' conflict.[19] Brazilian naval constructors such as Napoleão Level, Trajano de Carvalho and João Cândido Brasil planned new concepts for warships that allowed the country's Arsenals to retain their competitiveness with other nations.[20] All damage suffered by ships was repaired and various improvements were made to them.[21] In 1870, Brazil had 94 modern warships[22] and had the fifth most powerful navy in the world.[23]

Paraguayan War

Brazil's first line of military was his large and powerful navy. The navy fulfilled an important role by blocking Paraguayan access to the Plata basin and preventing its communication with the outside world. After the initial Paraguayan advance, the imperial navy went up the paraná and Paraguay rivers containing the Paraguayan advance. On 11 June 1865 the naval Battle of Riachuelo the Brazilian fleet commanded by Admiral Francisco Manoel Barroso da Silva destroyed the Paraguayan navy and prevented the Paraguayans from permanently occupying Argentine territory. The tactic used by Barroso to finally win the battle with the least possible losses was to break the Paraguayan wooden ships with the Brazilian ironclads. For all practical purposes, this battle decided the outcome of the war in favor of the Triple Alliance between Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay; from that point on it controlled the waters of the Río de la Plata basin up to the entrance to Paraguay. Following the victory after the Battle of Riachuelo, and running the gauntlet set up by Paraguayans at Bella Vista in the Battle of Paso de Mercedes the day before, the allied fleet advanced down the River Parana, not wanting to be cut off from its supply base.

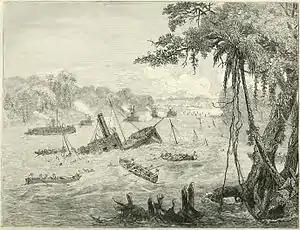

After the sequence of battles won by the Allies on 1866, an Allied council of war decided to use their navy to bombard and capture the Paraguayan battery at Curupayti. On 1 September, five Brazilian ironclads, Bahia, Barroso, Lima Barros, Rio de Janeiro and Brasil began bombarding the batteries at Curuzu, which continued the next day. That is when the Rio de Janeiro hit two mines and sank immediately along with her commander Américo Brasílio Silvado, and 50 sailors. Along with the Imperial Army land support, on 3 September, the fort was stormed. The defenders relied on the advantage of the wetlands and bushes around the fort. The fort was conquered after a heavy bombardment. The ironclad "Rio de Janeiro" had a hole blown in her bottom by a torpedo, and sank almost immediately

— the greater part of her crew, together with her captain, being drowned. This was the only ironclad which was sunk during the war.

Another great naval battle occurred in 1868; the Passage of Humaitá which was an operation of riverine warfare − the most lethal in South American history − in which a force of six Brazilian Navy armoured vessels was ordered to dash past under the guns of the Fortress of Humaitá on the Paraguay River. Some competent neutral observers had considered that the feat was very nearly impossible. The purpose of the exercise was to stop the Paraguayans resupplying the fortress by river, and to provide the Allies with a much-needed propaganda victory after 4 years of an exhaustive war. The attempt took place on 19 February 1868 and was successful, restoring the reputation of the Brazilian navy and the Empire of Brazil's financial credit, and causing the Paraguayans to evacuate their capital Asunción. Some authors have considered that it was the turning point or culminating event of the war. The fortress, by then fully surrounded by Allied forces on land or blockaded by water, was captured on 25 July 1868.

Expansion and end of the Empire

During the 1870s, the Brazilian Government strengthened the navy as the possibility of a war against Argentina over Paraguay's future became quite real. Thus, it acquired a gunboat and a corvette in 1873; an ironclad and a monitor in 1874; and immediately afterwards two cruisers and another monitor.[11][24] The improvement of the Armada continued during the 1880s. The Arsenals of the Navy in the provinces of Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Pernambuco, Pará and Mato Grosso continued to build dozens of warships. Also, four torpedo boats were purchased.[25]

On 30 November 1883, the Practical School of Torpedoes was created along with a workshop devoted to constructing and repairing torpedoes and electric devices in the Arsenal of Navy of Rio de Janeiro.[26] This Arsenal constructed four steam gunboats and one schooner, all with iron and steel hulls (the first of these categories constructed in the country).[25] The Imperial Armada reached its apex with the incorporation of the ironclad battleships Riachuelo and Aquidabã (both equipped with torpedo launchers) in 1884 and 1885, respectively. Both ships (considered state-of-the-art by experts from Europe) allowed the Imperial Brazilian Navy to retain its position as one of the most powerful naval forces.[27] By 1889, the navy had 60 warships[21] and was the fifth or sixth most powerful navy in the world.[28]

In the last cabinet of the monarchic regime, the Minister of the Navy, Admiral José da Costa Azevedo (the Baron of Ladário), left the reorganization and modernization of the navy unfinished.[21] The coup that ended the monarchy in Brazil in 1889 was not well accepted by the Navy. Imperial Mariners were attacked when they tried to support the imprisoned Emperor in the City Palace. The Marquis of Tamandaré begged Pedro II to allow him to fight back the coup; however, the Emperor refused to allow any bloodshed.[29] Tamandaré would later be imprisoned by order of the dictator Floriano Peixoto under the accusation of financing the monarchist military in the Federalist Riograndense Revolution.[30]

The Baron of Ladário remained in contact with the exiled Imperial Family, hoping to restore the monarchy, but ended up ostracized by the republican government. Admiral Saldanha da Gama led the Revolt of the Armada with the objective of restoring the Empire and allied himself with other monarchists who were fighting in the Federalist Revolution. However, all the attempts at restoration were violently crushed. High-ranking Monarchist officers were imprisoned, banished or executed by firing squad without due process of law and their subordinates also suffered harsh punishments.[31]

Some Vessels of the Imperial Navy

| Class | Type | Origin | In Service | Per unit (Name) | Photo | Displacement | N.B. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maria Teresa | Schooner | 1822–1827 | Participated in the War of Independence and the Cisplatine War. | ||||

| Vasco da Gama | Nau | 1822–1826 | Participated in the War of Independence. | ||||

| Pedro I | Nau | 1822–1827 |  | Participated in the War of Independence, his commander was Lord Cochrane Marquês do Maranhão. | |||

| Nictheroy | Frigate | 1822–1836 |  | It was the first captaincy ship of the Brazilian fleet, with notable achievements of the War of Independence and the Cisplatine War. | |||

| Liberal | Corvette | 1823–1844 | It was part of the Portuguese colonial fleet. The Brazilian Imperial Navy had outstanding performance of the War of Independence and the Cisplatine War. | ||||

| Maria da Glória | Clipper/Corvette | 1823–1830 |  | It was part of the Portuguese colonial fleet until 1823 when it was incorporated by Brazil. It participated in the War of Independence. In the Cisplatine War he stood out in the naval battle Lara Quilmes where he destroyed the Argentine frigate 25 de Mayo . | |||

| Real | Brig | 1823–1827 | It was part of the Portuguese colonial fleet, was captured by Brazilians. He was actively involved in the war of independence and the Cisplatine War. | ||||

| Oriental | Schooner | 1823–1827 |  | Participated in the cisplatin War. In 1827 was captured by Argentine Navy. | |||

| Dona Januária | Schooner | 1823–1845 |  | Participated in the cisplatin War. In 1827 was captured by Argentine Navy and renamed as Ocho Febrero In 1828 during the naval battle of Arregui was recaptured by the Empire of Brazil. | |||

| Imperatriz | Frigate | 1824–1836 |  | Participated in the cisplatin war. During the conflict he excelled in repelling the attacks of the Argentine navy | |||

| Bertioga | Schooner | 1825–1827 |  | Captured by the Argentines in the Battle of Juncal.In 1827 was captured by Argentine Navy. | |||

| Constituição | Frigate | 1826–1880 |  | Participated in the cisplatin war. Seizes two boats Argentine privateers during the conflict. | |||

| Abaeté | Schooner | 1839–1841 |  | Was part of the naval force which operated against Cabanagem. | |||

| Calíope | Brig | 1839–1860 | 194 ton | On December 17, 1851, participated in the forcing of the Tonelero Pass. | |||

| Amélia | Frigate | 1840–1859 |  | 594 ton | . | ||

| Dona Francisca | Corvette | 1845–1860 | 637 ton | On December 17, 1851, participated in the forcing of the Tonelero Pass. | |||

| Afonso | Frigate | 1848–1853 |  | 900 ton | Was fleet flagship during Battle of The Tonelero Pass in Platine War Sank in 1853. | ||

| Dom Pedro II | Corvette | 1850–1861 | .jpg.webp) | Participation in Battle of The Tonelero Pass Sank in 1861. | |||

| Recife | Corvette | 1850–1880 |  | Was flagship of a fleet during Battle of The Tonelero Pass in Platine War. | |||

| Bahiana | Corvette | 1851–1893 | 972 ton | In 1851, he went to Montevideo to join Admiral Grenfell's squad in the war against Argentine Rosas.It was set on fire and destroyed during the 1893 Armada Revolt. | |||

| Amazonas | Frigate | 1852–1897 |  | 1.800 ton | Relevant participation in Paraguayan War Was seriously damaged during Naval Revolt in 1897. | ||

| Ypiranga | Gunboat | 1854–1880 | .jpg.webp) | 325 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Beberibe | Corvette | 1854–1869 |  | 559 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. He had an important participation in the naval battle of Riachuelo and in the passage of the fortress of Humaita. | ||

| Belmonte | Corvette | 1856–1876 |  | 602 ton | Participation in Platine War and Paraguayan War. | ||

| Jequitinhonha | Corvette | 1854–1865 |  | 637 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War During the naval Battle of Riachuelo, it ran under the batteries of the strong enemies, having to be left by the crew. Not being able to get away from the beach, it was burned by the crew. | ||

| Parnahyba | Corvette | 1858–1868 |  | 637 ton | Participation in Uruguayan War and Paraguayan War. Special participation in Siege of Paysandú. | ||

| Anhambaí | Light Gunboat | 1858–1865 |  | Participation in and Paraguayan War. was captured by Paraguayan warships in January 1865. | |||

| Araguari | Gunboat | 1858–1882 |  | 400 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Ivahy | Gunboat | 1858–1870 |  | 415 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Iguatemi | Corvette | 1858–1882 | _no_alto_Paran%C3%A1_salvando_no_dia_7_de_Novembro_de_1868_a_lancha_a_vapor_Pimentel%252C_que_foi_a_pique%252C_e_na_qual_morreu_o_capit%C3%A3o_de_mar_e_guerra_Guilherme_Jos%C3%A9_dos_Santos_e_cinco_pra%C3%A7as.jpg.webp) | 400 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Ironclad Brasil | Ironclad warship | 1865–1890 |  | 1.518 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. Was damaged in Battle of Curuzu. | ||

| Mariz e Barros-class ironclad | Ironclad warship | 1865-1897 1865–1885 | 1-Mariz e Barros 2-Herval |  | 1.313 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | |

| Ironclad Tamandaré | Ironclad warship | 1865–1879 |  | 800 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. Was damaged in Battle of Curupayty. | ||

| Ironclad Barroso | Ironclad warship | 1866–1882 | .jpg.webp) | 980 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Ironclad Rio de Janeiro | Ironclad warship | 1865–1866 |  | 870 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. Sank after hitting two mines in Battle of Curupayty. | ||

| Cabral-class ironclad | Ironclad warship | 1865-1880 1865–1880 | 1-Cabral 2-Colombo | .JPG.webp) | 1.100 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | |

| Ironclad Lima Barros | Ironclad warship | 1866–1905 | .jpg.webp) | 1.700 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Ironclad Silvado | Ironclad warship | 1866–1880 |  | 1.335 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Monitor Bahia | Monitor (warship) | 1866–1882 | .JPG.webp) | 940 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Pará-class monitor | Monitor (warship) | 1866–1884 1866-1907 1867-1900 1868-1893 1868-1884 1868-1882 | 1-Pará 2-Rio Grande 3-Alagoas 4-Piauí 5-Ceará 6-Santa Catharina | 490 ton | Participation in Paraguayan War. | ||

| Battleship Riachuelo | Battleship | 1883–1910 |  | 5.700 ton | |||

| Afonso Celso Class | Gunboat | 1882–1900 | Afonso Celso/Trindade |  | 327 ton | . | |

| Torpedo-boat Class I | Torpedoboat | 1882–1900 | Nº1 Nº2 Nº3 Nº4 Nº5 |  | . | ||

| Alfa Class | Torpedoboat | 1883–1899 | Alfa Beta Gama | _-_NH_59871_-_cropped.png.webp) | . | ||

| Marajó | Gunboat | 1885–1893 | 430 ton | Participation in Naval Revolt by the Rebel Fleet. In 1893 he was set on fire by loyalist troops. | |||

| Imperial Marinheiro | Cruiser | 1884–1887 | .jpg.webp) | 726 ton | Sank in 1887. | ||

| Battleship Aquidabã | Battleship | 1885–1906 |  | 5.030 ton | Participation in Naval Revolt by the Rebel Fleet. Was damaged by torpedoes in naval battle of Anhatomirim, Santa Catarina Sank in 1906. | ||

| Iniciadora | Gunboat | 1885–1907 |  | 268 ton | |||

| Cruiser Almirante Barroso | Cruiser | 1884–1893 |  | 2.000 ton | Sank in 1893 during circumnavigation voyage. | ||

| Forges-et-Chantiers Ocean Monitor | Monitor (warship) | 1873–1893 1875-1893 | 1-Javary 2-Solimões |  | 3.700 ton | The two joined the Rebel Fleet during the Naval Revolt, Javary was sunk by the coastal artillery Fort Villagaignon. | |

| Trajano | Cruiser | 1873–1906 |  | 1.414 ton | He joined the Rebel Fleet during the Naval Revolt. | ||

| Battleship Sete de Setembro | Battleship | 1874–1893 |  | 2.174 ton | He joined the Rebel Fleet during the Naval Revolt, sunk in combat in 1893. | ||

See also

Footnotes

- Holanda, p.260

- Maia, p.53

- See Articles 102 and 148 of the Brazilian Constitution of 1824

- Carvalho (2007), p.193

- Lyra, p.84

- Pedrosa, p.289

- Holanda, pp.241–242

- Maia, pp.58–61

- Holanda, p.261

- Maia, pp.54–57

- Holanda, p.272

- Maia, pp.133–135

- Holanda. p. 264

- Maia, pp.205–206

- Maia, p.216

- Janotti, p.207, 208

- Carvalho (1975), p.181

- Holanda, p.266

- Salles (2003), p.38

- Maia, p.219

- Janotti, p.208

- Schwarcz, p.305

- Doratioto (1996), p.23

- Doratioto (2002), p.466

- Maia, p.225

- Maia, p.221

- Maia, p.221, 227

- Calmon (2002), p.265

- Calmon (1975), p.1603

- Janotti, p.66

- Janotti, p.209

References

- Brazilian Constitution of 1824. (in Portuguese)

- Bueno, Eduardo. Brasil: uma História. São Paulo: Ática, 2003. (in Portuguese)

- Calmon, Pedro. História de D. Pedro II. Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio, 1975. (in Portuguese)

- Calmon, Pedro. História da Civilização Brasileira. Brasília: Senado Federal, 2002.

- Carvalho, José Murilo de. Os Bestializados: o Rio de Janeiro e a República que não foi. 3. ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996. (in Portuguese)

- Carvalho, José Murilo de. D. Pedro II. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. (in Portuguese)

- Doratioto, Francisco. O conflito com o Paraguai: A grande guerra do Brasil. São Paulo: Ática, 1996. (in Portuguese)

- Doratioto, Francisco. Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. (in Portuguese)

- Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de. História Geral da Civilização Brasileira: Declínio e Queda do Império (2a. ed.). São Paulo: Difusão Européia do Livro, 1974. (in Portuguese)

- Janotti, Maria de Lourdes Mônaco. Os Subversivos da República. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1986. (in Portuguese)

- Lima, Manuel de Oliveira. O Império brasileiro. São Paulo: USP, 1989. (in Portuguese)

- Lyra, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Declínio (1880–1891). v.3. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1977. (in Portuguese)

- Lustosa, Isabel. D. Pedro I. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. (in Portuguese)

- Maia, Prado. A Marinha de Guerra do Brasil na Colônia e no Império (2a. ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Cátedra, 1975. (in Portuguese)

- Nabuco, Joaquim. Um Estadista do Império. Volume único. 4 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Aguilar, 1975. (in Portuguese)

- Nassif, Luís. Os cabeças-de-planilha. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Ediouro, 2007. (in Portuguese)

- Salles, Ricardo. Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens. Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional, 2003. (in Portuguese)

- Salles, Ricardo. Nostalgia Imperial. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 1996. (in Portuguese)

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. As Barbas do Imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos. 2. ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. (in Portuguese)

- Vainfas, Ronaldo. Dicionário do Brasil Imperial. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2002. (in Portuguese)

- Versen, Max von. História da Guerra do Paraguai. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1976. (in Portuguese)

- Vianna, Hélio. História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república, 15. ed. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1994. (in Portuguese)

- Kraay, Hendrik. Reconsidering Recruitment in Imperial Brazil, The Américas, v. 55, n. 1: 1-33, Jul. 1998.

External links

- Brazilian Navy official website (in Portuguese)

- Military Orders and Medals from Brazil (in Portuguese)

- South American Military History

.svg.png.webp)