Helicoprion

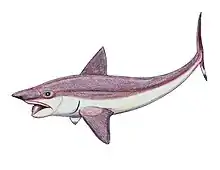

Helicoprion is a genus of extinct, shark-like[2] eugeneodontid holocephalian fish. Almost all fossil specimens are of spirally arranged clusters of the individuals' teeth, called "tooth whorls"— the cartilaginous skull, spine, and other structural elements have not been preserved in the fossil record, leaving scientists to make educated guesses as to its anatomy and behavior. Helicoprion lived in the oceans of the early Permian[3] 290 million years ago, with species known from North America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and Australia.[4] The closest living relatives of Helicoprion (and other eugeneodontids) are the chimaeras.[5]

| Helicoprion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tooth-whorl, Utah Field House of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | †Eugeneodontida |

| Family: | †Helicoprionidae |

| Genus: | †Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899[1] |

| Type species | |

| Helicoprion bessonowi Karpinsky, 1899 | |

| Species | |

| |

Description

In 2011, a tooth whorl from a Helicoprion was discovered in the Phosphoria site in Idaho. The tooth whorl measured 45 cm (18 in) in length. Comparisons with other Helicoprion specimens show that the animal that sported this whorl would have been 10 m (33 ft) in length, and another, even bigger tooth whorl that was discovered in 1980s (but was not published until 2013) which the discoverers dubbed IMNH 49382 or "Boise" was discovered at the same site. The whorl is incomplete, but in life it would have been 60 cm (24 in) long and would have belonged to an animal that possibly exceeded 12 m (39 ft) in length, making Helicoprion the largest known eugeneodont.[6]

Tooth-whorl

Until 2013, the only known fossils of this genus on record were their teeth, which were arranged in a "tooth-whorl" strongly reminiscent of a circular saw. As the skeletons of chondrichthyid fish are made of cartilage, including those of Helicoprion and other eugeneodonts, the entire body disintegrates once it begins to decay, unless exceptional circumstances preserve it. The tooth-whorl was not realized to be in the lower jaw until the discovery of the skull of a related genus of eugeneodont, Ornithoprion. The tooth-whorl represented all the teeth produced by that individual in the lower jaw; as the individual grew, the older, smaller teeth were moved into the center of the whorl by larger, newer teeth appearing. Models of the Helicoprion tooth-whorl have been made. In the 1994 book Planet Ocean: A Story of Life, the Sea, and Dancing to the Fossil Record, author Brad Matsen and artist Ray Troll describe and depict an example of such a model. They proposed that no teeth were present in the animal's upper jaw besides the crushing teeth for the whorl to cut against. The two envision the living animal to have a long and very narrow skull, creating a long nose akin to the modern-day goblin shark. According to their studies, the fossils that have been found are essentially a growth ring, as each set of new teeth pushes the previous set into the whorl.[7]

For over a century, whether the tooth-whorl was situated in the lower jaw was not certain. Older reconstructions placed the whorl in the front of the lower jaw. A 2008 reconstruction, created by Mary Parrish under the direction of Robert Purdy, Victor Springer, and Matt Carrano for the Smithsonian, places the whorl deeper into the throat,[3] although other studies did not accept this conclusion.[8][9] A 2013 study based on new data places the tooth-whorl at the back of the jaw, where the tooth-whorl occupied the entire mandibular arch.[5]

In his 1939 article, author Harry E. Wheeler describes another Helicoprion fossil, based on the species H. sierrensis, collected by J. H. Menke, that resides at the University of Nevada, W. M. Keck Earth Science and Mineral Engineering Museum. This fossil is number 1002 and is currently on display in case 62. The mouth consists of a whorl separated into three and a quarter volutions. The biggest diameter is about 170 mm (6.7 in). The whorls have a separation of about 1 mm (0.039 in) in the first volution, and it goes to about 8 mm (0.31 in) at the largest whorl displayed. The specimen has a total of about 32 teeth in the first volution, 36 in the second, and 41 in the last. The teeth at the end of the first volution are about 7 mm (0.28 in) long and are about 2.4 in (61 mm) in width, reaching about 40 mm (1.6 in) long and 9.5 wide at the end of the third. The teeth are symmetrically opposed to one another.[10]

Additionally, other extinct fish, such as the Onychodontiformes, have analogous tooth-whorls at the front of the jaw, suggesting that such whorls are not as substantial of an impediment to swimming as suggested in Purdy's hypothesis. While no complete skulls of Helicoprion have been officially described, the fact that related species of chondrichthyids had long, pointed snouts suggests that Helicoprion did, as well.

Distribution

Helicoprion species proliferated greatly during the early Permian. Fossils have been found in the Ural Mountains, Western Australia, China[11] (together with the related genera Sinohelicoprion and Hunanohelicoprion), and Western North America, including the Canadian Arctic, Mexico, Idaho, Nevada, Wyoming, Texas, Utah, and California. More than 50% of Helicoprion specimens are known from Idaho, with an additional 25% being found in the Ural Mountains.[4] Due to the fossils' locations, the various species of Helicoprion may have lived off the southwestern coast of Gondwana, and later, Pangaea.[12]

Species

H. bessonowi

Helicoprion was first described by Alexander Karpinsky in 1899 from a fossil found in Artinskian-age limestones of the Ural Mountains.[13] Karpinsky named the type species Helicoprion bessonowi; Oliver Perry Hay originally described the species. This species can be differentiated from others by a short and narrowly spaced tooth whorl, backward-directed tooth tips, obtusely-angled tooth bases, and a consistently narrow whorl shaft.[4]

One of two Helicoprion species described by Wheeler in 1939, H. nevadensis, is based on a single partial fossil found in 1929 by Elbert A Stuart.[10] It was reported as having originated from the Rochester Trachyte deposits, which Wheeler considered to be of Artinskian age. However, the Rochester Trachyte is in fact Triassic, and H. nevadensis likely did not originate in the Rochester Trachyte, thus rendering its true age unknown. Wheeler differentiated H. nevadensis from H. bessonowi by its pattern of whorl expansion and tooth height, but Leif Tapanila and Jesse Pruitt showed in 2013 that these were consistent with H. bessonowi at the developmental stage that the specimen represents.[4]

Based on isolated teeth and partial whorls found on the island of Spitsbergen, Norway, H. svalis was described by Stanisław Siedlecki in 1970. The type specimen, a very large whorl, was noted for its narrow teeth that apparently are not in contact with each other, but this seems to be a consequence of only the central part of the teeth being preserved, according to Tapanila and Pruitt. Since the whorl shaft is partially obscured, H. svalis cannot be definitely assigned to H. bessonowi, but it closely approaches the latter species in many aspects of its proportions. With a maximum volution height of 72 mm (2.8 in), H. svalis is similar in size to the largest H. bessonowi, which has a maximum volution height of 76 mm (3.0 in).[4]

H. davisii

H. davisii was described initially from a series of 15 teeth found in Western Australia. They were described by H. Woodward in 1886 as a species of Edestus, E. davisii. Upon naming H. bessonowi, Karpinsky also reassigned this species to Helicoprion, an identification subsequently supported by the discovery of two additional and more complete tooth whorls in Western Australia. The species is characterized by a tall and widely spaced tooth whorl, with these becoming more pronounced with age. The teeth also noticeably curve forwards. During the Kungurian and Roadian, this species was very common worldwide.[4]

H. ferrieri was originally described as a species of the genus Lissoprion in 1907, from fossils found in the Phosphoria Formation of Idaho. An additional specimen, tentatively referred to H. ferrieri, was described in 1955. That specimen was found in Wolfcampian-age quartzites exposed on China Mountain, six miles southeast of Contact, Nevada. The 100-mm-wide fossil consists of one and three-quarters whorls and about 61 preserved teeth. Due to weathering, the rest of the fossil was lost and the preserved section is distorted from slippage of the host rock.[13] While initially differentiated using the metrics of tooth angle and height, Tapanila and Pruitt considered these characteristics to be intraspecifically variable, reassigning H. ferrieri to H. davisii.[4]

H. jingmenense was described in 2007 from a nearly complete tooth whorl with four and a third volutions (part and counterpart) found in the Lower Permian Qixia Formation of Hubei Province, China. It was discovered during road construction. The specimen is very similar to H. ferrieri and H. bessonowi, though it differs from the former by having teeth with a wider cutting blade, and a shorter compound root, and differs from the latter by having fewer than 39 teeth per volution.[11] Tapanila and Pruitt argued that the specimen was partially obscured by the surrounding matrix, resulting in an underestimation of tooth height. Taking into account intraspecific variation, they synonymized it with H. davisii.[4]

H. ergassaminon

H. ergassaminon, the rarer species from the Phosphoria Formation, was described in detail within a 1966 monograph by Svend Erik Bendix-Almgreen. The holotype specimen ("Idaho 5"), now lost, bore breakage and wear marks indicative of its usage in feeding. Several referred specimens exist, none of which show wear marks. This species is roughly intermediate between the two contrasting forms represented by H. bessonowi and H. davisii, having tall but narrowly-spaced teeth. Its teeth are also gently curved, with obtusely-angled tooth bases.[4]

Other material

Several large whorls are difficult to assign to any particular species group, H. svalis among them. IMNH 14095, a specimen from Idaho, appears to be similar to H. bessonowi, but it has unique flange-like edges on the apices of its teeth. IMNH 49382, also from Idaho, has the largest known whorl diameter at 56 mm (2.2 in) for the outermost volution (the only one preserved), but it is incompletely preserved and still partially buried.[4]

H. mexicanus, named by F.K.G. Müllerreid in 1945 and supposedly distinguished by its tooth ornamentation, has a holotype that is currently missing, but its morphology was similar to IMNH 49382. In the absence of other material, it is currently a nomen dubium. Vladimir Obruchev described H. karpinskii from two teeth in 1953. He provided no distinguishing traits for this species, thus it must be regarded as a nomen nudum.[4]

References

- Карпинскій, А. (1899). Объ остаткахъ eдестидъ и о новомъ ихъ родѣ Helicoprion [On the edestid remains and the new genus Helicoprion]. Записки Императорской Академіи Наукъ (Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences). По Физико-математическому отдѣленіи (Physics and Mathematics section) (in Russian). 8 (7): 1–67; Pl. I–IV.

Also printed as "Ueber die Reste von Edestiden und die neue Gattung Helicoprion". Записки Императорскаго С.-Петербургскаго Минералогическаго Обществ(Notes of the Imperial St. Petersburg Mineralogical Society). 2 (in German). 36: 361–476. 1899; Pl. I–IV. [Reprinted (1899). St. Petersburg: C. Birkenfield. pp. 1–111. urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00073910-2.] - Viegas, Jennifer (February 27, 2013). "Ancient shark relative had buzzsaw mouth". science.nbcnews.com.

- Purdy, Robert (February 29, 2008). "The Orthodonty of Helicoprion". paleobiology.si.edu. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018.

- Tapanila, L.; Pruitt, J. (2013). "Unravelling species concepts for the Helicoprion tooth whorl" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 87 (6): 965–983. doi:10.1666/12-156. S2CID 53587115.

- Tapanila, L.; Pruitt, J.; Pradel, A.; Wilga, C.D.; Ramsay, J.B.; Schlader, R.; Didier, D.A. (2013). "Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion". Biology Letters. 9 (2): 20130057. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0057. PMC 3639784. PMID 23445952.

- Udurawane, Vasika. "Buzzsaw-toothed leviathans cruised the ancient seas". eartharchives.org.

- Matsen, Brad; Troll, Ray (1994). Planet Ocean: A Story of Life, the Sea, and Dancing to the Fossil Record. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 9780898157789.

- Lebedev, O.A. (2009). "A new specimen of Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899 from Kazakhstanian Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and function". Acta Zoologica. 90: 171–182. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00353.x. ISSN 0001-7272.

- Brian Switek (February 29, 2008). "Unraveling the Nature of the Whorl-Toothed Shark". Laelaps. Wired. p. 3. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- Wheeler, H. E. (1939). "Helicoprion in the Anthracolithic (Late Paleozoic) of Nevada and California, and its Stratigraphic Significance". Journal of Paleontology. 13 (1): 103–114. JSTOR 1298628.

- Chen, Xiao Hong; Long, Cheng; Yin, Kai Guo (August 2007). "The first record of Helicoprion Karpinsky (Helicoprionidae) from China". Chinese Science Bulletin. 52 (16): 2246–2251. Bibcode:2007ChSBu..52.2246C. doi:10.1007/s11434-007-0321-y. S2CID 96676181.

- Lebedev, Oleg. "A new specimen of Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899 from Kazakhstanian Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and function". Acta Zoologica – via Research Gate.

- Larson, E. R.; Scott, J. B. (1955). "Helicoprion from Elko County, Nevada". Journal of Paleontology. 29 (5): 918–919. JSTOR 1300414.

Further reading

- Hay, Oliver Perry (1909). "On the nature of Edestus and related genera, with descriptions of one new genus and three new species". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 37 (1699): 43–61. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.37-1699.43; Pl. 12–15.

- Карпинскій, А. (1911). "Замѣчанія о Helicoprion и о другихъ едестидахъ". Извѣстія Императорской Академіи Наук = Bulletin de l'Académie Impériale des Sciences de St.-Pétersbourg. VI Серия = VI Série. 5 (16): 1105–1122.

- Teichert, Curt (1940). "Helicoprion in the Permian of Western Australia". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (2): 140–149. JSTOR 1298567.

- Woodward, Henry (1886). "On a Remarkable Ichthyodorulite from the Carboniferous Series, Gascoyne, Western Australia". Geological Magazine. New Series. Decade III. 3 (1): 1–7. Bibcode:1886GeoM....3....1W. doi:10.1017/S0016756800144450.

- Yabe, H. (1903). "On a Fusulina-Limeston with Helicoprion in Japan". The Journal of the Geological Society of Japan. 10 (113): 1–13. doi:10.5575/geosoc.10.113_1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Helicoprion. |

Sharks portal

Sharks portal Paleontology portal

Paleontology portal