Green Lake (Wisconsin)

Green Lake — also known as Big Green Lake (to distinguish it from Little Green Lake, which is near Markesan)— is a lake in Green Lake County, Wisconsin, United States. Green Lake has a maximum depth of 72.24 m (237.0 ft), making it the deepest natural inland lake in Wisconsin and the second largest by volume. The lake covers 29.72 km2 (7,340 acres) and has an average depth of 30.48 m (100.0 ft). Green Lake has 43.94 km (27.30 mi) of diverse shoreline, ranging from sandstone bluffs to marshes.[2]

| Green Lake | |

|---|---|

| Big Green Lake | |

| |

Green Lake  Green Lake | |

Hydrographic Map of Green Lake Wisconsin | |

| Location | Green Lake County, Wisconsin, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°49′28″N 88°57′52″W |

| Type | Dimictic |

| Etymology | Green appearance of the water |

| Part of | Big Green Lake Watershed |

| Primary inflows | Silver Creek,

White Creek, Dakin Creek, Hill Creek, Wurches Creek, Roy Creek, Spring Creek, Assembly Creek |

| Primary outflows | Puchyan River |

| Catchment area | 277.9 km2 (107.3 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Managing agency | Green Lake Association, Green Lake Sanitary District |

| Max. length | 11.75 km (7.30 mi) |

| Max. width | 3.219 km (2.000 mi) |

| Surface area | 2,973 ha (7,350 acres) |

| Average depth | 30.48 m (100.0 ft) |

| Max. depth | 72.24 m (237.0 ft) |

| Water volume | 0.9390 km3 (761,300 acre⋅ft) |

| Residence time | 21 years |

| Salinity | 502.80 - 532.88 uS/cm |

| Shore length1 | 43.94 km (27.30 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 242.3 m (795 ft)[1] |

| Max. temperature | 27.2 °C (81.0 °F) Highest average, 2018 |

| Frozen | 87 days |

| Settlements | Green Lake, Wisconsin |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

History

First Settlers

The Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, also referred to as the Winnebago, were some of the first residents in the Green Lake Area.[3] Green Lake, also known as Daycholah, is a spiritual place for the Winnebago. One legend describes how one must bring gifts for the Water Spirit that lives under the lake in order to enter.[4] With the increase of European settlers, the Winnebago were subject to forced relocation by the United States government several times. Once they were removed from the Green Lake area, they were moved to Iowa until the establishment of a reservation in Blue Earth County, Minnesota.[5]

Chief Highknocker

The last reigning chief of the Green Lake area. He was born in 1820 with the given name Henaga. He spent most of his life around the lake but was forced to move further north because of the ever-increasing number of settlers. He continued visiting Green Lake every summer with other members of the tribe. On August 12th, 1911, at the age of 91, he drowned after getting a cramp while swimming in the lake. His grave at Dartford Cemetery is marked by a large boulder with an inscription from the community.[4]

European Settlement

French settlers initially called the lake Lac Verde. In 1836, Wisconsin land could be purchased through the Green Bay Land Office at $1.25 per acre.[4] Anson Dart built a dam with Smith Fowler and his own son in an effort to raise the lake level, leading to the namesake of Dartford (now called Green Lake). The next year, Dart built a sawmill that used the mill race created by the dam. The dam's success in raising lake level allowed different types of mills to be constructed around Green Lake. Many large, wooden hotels and one short-lived casino populated the north shore during the late 19th century in the city of Green Lake, but most have burned down. One was the Pleasant Point, which opened in the early 1880s.[6] The name "Green Lake" comes from the green color of its deep waters.[7] The city of Green Lake is located on the northeast shore in Dartford Bay.

Lone Tree Farm

Because of the proximity to the lake, the land was ideal for farming. In 1888, Victor and Jessie Lawson purchased a plot of land called Lone Tree Point that would later become Lone Tree Farm. Victor Lawson was a newspaper editor and philanthropist, and his wife Jessie was the primary planner for their estate. Together, the Lawson's developed approximately 1,100 acres of land that is still used today as a religious conference center. Some features of the estate include roads, a boathouse, and, at the time, the largest dairy barn in Wisconsin.[3]

Geography

The City of Green Lake, with a population of 828 as of 2018,[8] is located on the northeast shore at the outflow of the Puchyan River.[2] There are six public lands and parks on or near the lake: Sunset Park, Daycholah Lookout, Spring Lake County Park, Hattie Sherwood Park, Deacon Mills Park, and Playground Park. The lake has three beaches: Hattie Sherwood Beach, Dodge Country Park Beach, and Sunset County Park. There are eight public access boat landings on Green Lake.[9]

Green Lake lies within the Big Green Lake drainage basin which covers three counties. The majority of the drainage basin is in Green Lake County, with small portions of the drainage basin within the western edges of both Winnebago and Fond Du Lac counties. It lies within the Upper Fox River drainage basin, which is part of the Great Lakes drainage basin.[10]

Spring Lake and Twin Lakes are three small lakes south of the southern shore that flow into Green Lake.[11]

Green Lake has several bays, coves, points and peninsulas. On the northern shore, from West to East, are: Beyers Cover at the western edge of the northern shore; Sugar Loaf, a peninsula with a tall bluff; Norwegian Bay, bounded on the West by Sugar Loaf; Pigeon Cove and Malcolm Bay on the central north shore; and Dartford Bay, surrounded by the City of Green Lake at the primary outflow of the Puchyan River . Along the southern shore, from West to East: Blackbird point, a small protrusion; Dickinson Bay, a small bay on the west-central southern shore; Sandstone Bay; and Sandstone Bluff, a point that bounds Sandstone Bay on the East.[11]

Land Use in Green Lake Watershed[12]

| Land Cover | Acres | % Total Area |

| Agriculture | 44,639.76 | 65 |

| Open Land/Water | 10,665.47 | 15.53 |

| Forest | 6,016.07 | 8.76 |

| Wetland | 3,935.17 | 5.73 |

| Suburban | 2,211.38 | 3.22 |

| Urban | 597.49 | 0.87 |

| Grassland | 556.28 | 0.81 |

| Barren Land | 48.07 | 0.07 |

| Total | 68,676.55 | 100 |

Geology

The Green Lake basin exists within a river-carved valley that originated prior to the Wisconsin glaciation. It is likely that the movement of the glacier also deepened the valley, as well as smoothed its sides. The valley finally flooded when a recessional moraine about 90 m (300 ft) high blocked the exit of water at the west end of the basin during the Cary stage of glacial reduction.[13] The basin is composed mainly of Potsdam sandstone. Beginning just below the water surface is a layer of Madison Sandstone (7.5 m (25 ft) thick), followed by dolomite, St. Peter Sandstone (30 m (98 ft) thick), and Trenton limestone. The shoreline is diverse, ranging from sandy beaches to swamps to steep cliffs where the bedrock is exposed, such as in the image on the left.[14]

The glacial activity that created the Green Lake moraine also sculpted the surrounding topography. The land is covered in drumlins, parallel troughs and ridges with rolling tops that rise to a height of 30–60 m (98–197 ft). These ridges are covered in a thin layer of glacial till that is composed mainly of sand eroded from the native sandstones in the area.[14]

The water level increase caused by the dam at the head of the Puchyan has had profound impacts on the shoreline of the lake, mainly in the creation of many immature beaches. The maturity of these beaches is dictated by the composition of the shore, where looser till material erodes much more quickly than even the fragile sections of exposed bedrock. These looser areas mature more quickly. In more mature areas, boulders from the strata that are kept pushed against the shore by ice provide protection from erosion.[14]

Hydrology

Drainage Basin

At 72.24 m (237.0 ft) deep and with a volume of 0.9390 km3 (761,300 acre⋅ft),[2] Green Lake is the deepest natural inland lake in the state and second-largest by volume.[13] Only Lake Wazee, a man-made lake, is deeper, and only Lake Winnebago has a larger volume. The deepest and steepest part of the basin is near the west end, while the eastern third is more shallow. The maximum gradient is 33% at Lucas Bluff, a large rock face on the southeast shore. There are shoals at Malcom Bay and the east end of the lake[14] The lake has a maximum fetch of 11.75 km (7.30 mi). This allows a theoretical maximum surface wave height of 1.14 m (3.7 ft).

Green Lake is within the Big Green Lake Watershed, which has a catchment area is 277.9 km2 (107.3 sq mi). The drainage basin lies mostly in Green Lake County, but extends east into Fond du Lac and Winnebago County. In addition to Green Lake, the drainage basin includes Spring Lake and the East and West Twin Lakes.[12]

Tributaries and Outlet

The components of the Green Lake basin water budget are, in approximate percentages: direct precipitation, 51%; surface water, 41%; ground water, 8%. Eight creeks make up the surface water supply, the largest being Silver Creek, which flows into the east end of the lake. The remaining seven are Hill Creek, White Creek, Dakin Creek, Wurches Creek, Roy Creek, Spring Creek, Assembly Creek. The primary outflow is the Puchyan River, a tributary to the upper Fox River that lies in the Lake Michigan drainage basin.[13] This makes Green Lake a drainage lake, a lake in which surface outflow dominates.[15] A dam in the outlet keeps the water level in the lake around 1.52 m (5.0 ft) higher than the natural level.[14] Green Lake has a retention time of 21 years, relatively long for a temperate lake of its size. This has implications for lake health because with very low rates of flushing, there is a large lag for reversion of fertility changes.[13]

Water Chemistry and Quality

Temperature

The highest recorded average temperature in 2018 was 27.2 °C (81.0 °F).[16] The median ice cover duration of the last 67 seasons is 87 days.[17] Green Lake has lost over 25 days of ice cover since 1940, and at the current rate, will continue to lose one day of ice cover every three years. At this rate, Green Lake is estimated to have zero ice cover by 2087.[13]

Oxygen

Dissolved oxygen (DO) is key to the health of aquatic ecosystems. It is essential for the metabolism of all aerobic organisms, therefore controlling their distribution, behavior, and growth within the ecosystem. If oxygen is depleted, these organisms will die or not do well. Oxygen also reacts with many other compounds, influencing their availability and chemical forms.[15] Due to its thermal stratification, the concentration of DO in Green Lake decreases through the thermocline and into the hypolimnion.[13] One of the most interesting characteristics of the Green Lake DO profile is a pronounced metalimnetic oxygen minimum, documented through the literature since the 1900s at a depth of 10 m (33 ft) and with a thickness of ~3 m (9.8 ft). The dissolved oxygen drops from ~9 mg/L to ~4 mg/L before rebounding and slowly decreasing into the hypolimnion. Based on other chemical characteristics such as pH and chlorophyll fluorescence at this depth, it is likely that the metalinetic oxygen minimum results from a concentration of respiring plankton.[18] The quality of the environment can be judged by oxygen levels. Because the DO level is <5 mg/L, the lake was classified as "impaired" by the Wisconsin DNR in 2014. The low DO in this band poses a danger for aerobic organisms and has the potential to expand.[13]

Another threat facing the lake is hypolimnetic oxygen depletion. A paleolimnological sediment analysis conducted in the deep basins of the lake showed trends of oxygen depletion since 1950. Though the deep waters are not yet devoid of oxygen, the oxygen is being depleted faster than it was in 1950. This is a result of increased nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorus) availability in the epilimnion, which increases biological productivity. As these organisms die, sink, and aerobically decompose, oxygen is depleted.[13]

Nitrogen and Phosphorus

Nitrogen is essential in many biomolecules, such as amino acids, and has roles in biosignalling. It is also a major excretory product of livestock and a key ingredient in fertilizers, both of which play a key role in the agriculturally-dense Big Green Lake drainage basin.[15][12] Phosphorus is also a key element in living things, constituting molecules such nucleic acids and phospholipid membranes. Like nitrogen, it is a major excretory product of livestock and a key ingredient in fertilizers.[15] Nitrogen and phosphorus are often identified as limiting nutrients in aquatic ecosystems, since they are limited in availability relative to their demand in the ecosystem.[15] Should the availability of phosphorus increase, algal growth will increase, decreasing water quality.[15] Increase in phosphorus concentration are the most pressing threat to the health of Green Lake[13] Total phosphorus values in the epilimnion range from 10 μg/L to 50 μg/L. Due to variation and associated confidence limits in the average total phosphorus level of 17.2 μg/L, the lake does not meet the "impairment" designation of >15 μg/L of phosphorus. It is likely, however, that the lake is impaired.[13] Increasing phosphorus is likely to blame for the hypolimnetic oxygen depletion and metalimnetic oxygen minimum mentioned in the previous section. Because most of the tributaries enter on the east end of the lake, phosphorus has generally been higher in the east end.[13] Current lake management efforts focus heavily on monitoring and reducing phosphorus loading within the drainage basin by controlling erosion, runoff, and fertilizer use.[13]

The specific conductance ranges from 502.80 - 532.88 microSiemens per centimeter.[18]

Flora and Fauna

Flora

Aquatic vegetation found in most recent survey[19]

| Emergent | Floating | Submerged |

| Bristly sedge | White water lily | Coontail |

| Stiff arrowhead | Muskgrass | |

| Hardstem bulrush | Aquatic moss | |

| Softstem Bulrush | Common waterweed | |

| Common bur-reed | Water stargrass | |

| Cattail | Northern watermilfoil | |

| Needle spikerush | Slender Naiad | |

| Stoneworts | ||

| Slender Pondweed | ||

| Leafy pondweed | ||

| Fries' pondweed | ||

| Illinois pondweed | ||

| Longleaf pondweed | ||

| White-stem Pondweed | ||

| Clasping-leaf pondweed | ||

| Stiff pondweed | ||

| Flatstem pondweed | ||

| White water crowfoot | ||

| Spiral ditchgrass | ||

| Sago Pondweed | ||

| Wild celery | ||

| Horned pondweed |

The most abundant native aquatic plant species found in Green Lake, based on littoral frequency of occurrence, are: Coontail, at 53%; Sago pondweed, at 15%; Wild celery, at 13%; and White water-crowfoot, at 12%.[20]

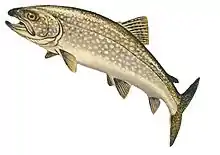

Fishes

Green Lake is a highly productive and highly utilized fishery. Because of its depth, it supports both a warm-water and cold-water fishery, though species of the warm-water fishery predominate.[13] 40 species of fish have been documented in Green Lake.[21]

.jpg.webp)

Common Warm-water Fishery Species

- Largemouth bass

- Smallmouth bass

- Walleye

- Northern pike

- White bass

- Channel catfish

- Bluegill

- Black crappie

- White crappie

- Yellow perch

- Rock bass

- Muskellunge (stocked)

- Common carp

Cold-water Fishery

- Cisco

- Lake trout (stocked)

- Splake

- Brook trout

- Brown trout

- Rainbow trout

Ecology

Ecology of the Warm-water Fishery

Both small and largemouth bass reproduce naturally and maintain stable populations in the lake. Largemouth are susceptible to habitat loss due to the low amount of vegetated littoral habitat. Smallmouth bass thrive in the lake due to the rocky and steep bottom, and walleye naturally maintain a low population in Green Lake. Targeted fishing, limited littoral habitat, late spring warming, and predation on eggs, fry, and fingerlings limit the size of the population.[13] The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) does not stock walleye in the lake due to genetic concerns. Similarly, northern pike are also limited by spawning habitat degradation by development, boating, and carp. Angling also puts heavy pressure on the population, so size and bag limits have been implemented to help reduce the strain. Panfish maintain healthy populations, but angling and shoreline development represent main threats. The loss of woody vegetation along the shoreline is especially damaging.[13]

Studies have also focused on the health of non-game fish populations as they related to ecosystem health. In Green Lake, species such as the blackchin shiner, Iowa darter, and mottled sculpin are all intolerant to environmental disruption and therefore serve as indicator species of lake health. In addition to carp disturbance, shoreline development, and boating disturbance, cyanobacteria blooms, zebra mussels, and filamentous algae growth may also represent limiting factors to habitat health and fish growth.[21]

Ecology of the Cold-water Fishery

Cisco are native to Green Lake and are regularly fished. They are very sensitive to environmental change, and their populations are in flux. Recent surveys in Green Lake have shown that the cisco population has slightly declined, possibly due to the ecological effects of eutrophication. Climate change severely threatens cisco, and their populations could be reduced by 30-70%. Lake trout are the prized species of the cold-water fishery, and the WDNR stocks 25,000 yearlings annually. These fish are raised at the Green Lake Cooperative fish rearing facility, which is owned by the Green Lake Sanitary District and operated in conjunction with the WDNR. There have been reports of scarring on adult lake trout, suggesting possible conflict with muskellunge in the boundaries between the warm and cold-water fisheries. A main threat facing the fish of the cold-water fishery is oxygen depletion, especially in the deep west basin.[13] The Wisconsin inland lake record lake trout was caught on Big Green Lake by Joseph Gotz on June 1, 1957 and weighed 35 lb 4 oz (16.0 kg). The Wisconsin record cisco was caught on Big Green Lake on June 12, 1969 by Joe Miller and weighed 4 lb 10.5 oz (2.11 kg).[22]

Aquatic Vegetation and Algae

A majority of aquatic vegetation was found growing at a depth of 14 feet (4.27 m) and a maximum depth of 23 feet (7.01 m). Of all the observed species, coontail and hybrid water milfoil were the highest frequency of occurrence. Coontail is a common aquatic species in Wisconsin and able to survive and thrive in areas with light deficiency as it receives a majority of nutrients from the water. The ability to grow in deeper areas of the littoral zone allows coontail to provide habitat for invertebrates and fish.[13] Species like common carp and zebra mussels have contributed to the degeneration of shallow aquatic plant species. The high nutrient concentrations attribute to algal growth that may have future negative effects.[13]

Environmental Concerns

Pollution

Prior to European settlement, the lake was considered to be oligotrophic, meaning that it had low biological productivity and good water quality based on a trophic state index. Green Lake is now considered to be mesotrophic lake because of increased nutrient loading from both natural and anthropogoenic causes. Water quality has since decreased and is considered “impaired” per standards laid out in the Clean Water Act by the Environmental Protection Agency.[7]

Invasive Species

Invasive Flora

Hybrid water milfoil and curly-leaf pondweed have been documented in Green Lake since 1971. A 2014 survey showed that hybrid water milfoil increased in dominance to make up 25% of the aquatic plant species. The most frequently found singular plant species in the lake in 2015 was Eurasian water milfoil at 20% of relative frequency. Another invasive plant species, the spiny naiad (Najas marina), was documented in a 2007 WDNR survey, but was not observed in the 2014 survey.[23]

- Eurasian water milfoil

- Hybrid water milfoil

- Curly-leaf pondweed

- Purple loosestrife

- Reed canary grass

Invasive Fauna

Common carp have contributed to the degradation of plant species and fish spawning locations in the shallow areas of the lake in addition to the Silver Creek inflow and nearby County K Marsh. Placing carp barriers have contributed to a regeneration of the aquatic plant species in the Silver Creek inflow, but not for the County K Marsh. The unsuccessful control in County K Marsh is attributed to the high levels of phosphorus that enter from Silver Creek.[13] Both zebra and quagga mussel species positively influence the growth of the green algae species Cladophora glomerata.[24] The Cladophora population has been steadily increasing since 1921 to now nuisance levels. This particular green algae thrives in the high nutrient concentrations and its high density has ecological consequences. Some of these include encouraging the expansion of zebra and quagga mussel populations and inhibiting the spawning of native fish populations.[25]

- (German) Common carp

- Zebra mussels

- Quagga mussels

- Freshwater Jellyfish

Development and Management

There are three organizations associated with managing Green Lake: Green Lake Association, Green Lake Sanitary District, and the Green Lake Conservancy (also known as Green Lake Preservation Society).[13]

Green Lake Conservancy

The Green Lake Conservancy is an organization dedicated to preserving the lands surrounding Green Lake. The organization works by acquiring environmentally sensitive properties, such as woods or wetlands, and protecting them by placing them into conservancy. They are then cooperatively managed with the WDNR and Green Lake Sanitary District. To date, they have protected 15 properties around the lake.[26]

Green Lake Association

Founded in 1951, the Green Lake Association (GLA) is a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit, membership organization. Their membership includes nearly 800 households and businesses within the drainage basin. They focus on the water quality of the Big Green Lake drainage basin. [27]

Recreation

The lake and its surrounding topography have opportunities for a large range of recreational activities year-round.

During the summer, activities such as boating, water skiing, wakeboarding, tubing, swimming, sailing, jet skiing, kayaking, canoeing, paddleboarding, and fishing are common. The Green Lake Sailing School offers sailing lessons to all age groups during the summer, and there are frequent regattas for different boat classes. The marina in Dartford Bay offers access to town by boat and leads into Deacon Mills Park.

Off of the water, there is an extensive network of bike trails and routes available, including "Loop the Lake," a 24 mile trail which circumnavigates the perimeter of the lake. The Green Lake Conservancy and Green Lake Sanitary district maintain properties that offer public hiking trails at various locations. Green Lake has several golf courses around it, including Tuscumbia Country Club, the oldest course in the state.

The entire lake gradually freezes over during the winter. On the ice, there is ice skating, hockey, ice fishing, snowmobiling, and iceboating. There are frequent iceboat races hosted by the Green Lake Yacht Club.

Off of the ice, there are opportunities for cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and snowmobiling.[28]

In popular culture

- A season 4 episode of the Discovery Channel series A Haunting, called Legend Trippers, takes place in Green Lake and the nearby town of Montello.

References

- "Google Earth". Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- "Green Lake (Big Green Lake) – Green Lake County, Wisconsin DNR Lake Map Date – Jun 1974 - Historical Lake Map - Not for Navigation" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. June 1974. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Egbert, Diane (2019). Dartford Days: A Postcard History of Early Green Lake, Wisconsin. New Berlin, Wisconsin: Traxion. pp. 42–57, 190–192, 198–199.

- Heiple, Robert W. and Emma B. (1976). A Heritage History of Beautiful Green Lake Wisconsin. Ripon, Wisconsin: Mc Millan Printing Company. pp. 21, 26–28, 38–48.

- Lass, William (1962). The Removal From Minnesota of the Sioux and Winnebago Indians. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/38/v38i08p353-364.pdf: University of Nebraska Press. p. 353.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Portrait and Biographical Album of Green Lake, Marquette and Waushara Counties, Wisconsin ... Acme Publishing Company. 1890.

- "Wisconsin's Largest Water Areas" in Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau. State of Wisconsin 2005-2006 Blue Book. Madison: Wisconsin Legislature Joint Committee on Legislative Organization, 2005, p. 691.

- "The City of Green Lake". Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- "Green Lake". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

- "Green Lake Watershed Information System". Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- "Green Lake (Big Green Lake) – Green Lake County, Wisconsin DNR Lake Map Date – Jun 1974 - Historical Lake Map - Not for Navigation" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. June 1974. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- "BIG GREEN LAKE TWA WQM PLAN 2017". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2017.

- Sesing, Mark (2015). "A Lake Management Plan for Green Lake" (PDF). Green Lake Sanitary District.

- Birge, Edward (1914). The Inland Lakes of Wisconsin. Madison WI: State of Wisconsin.

- Wetzel, Robert G. (2001). Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems. Elsevier Science.

- 2020 Big Green Lake Water Quality Report Showing Averages 1989 - 2020 (Report). Green Lake Sanitary District. 2020.

- "Duration of Ice on Big Green Lake (1939/40 - 2005/06 Winter Seasons)". Wisconsin State Climatology Office. 2006. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Watras, Carl (November 1, 2014). "Microstratification and Oxygen Depletion in Green Lake, Wisconsin: A Pilot Study" (PDF). The Nelson Institute. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- Green Lake Aquatic Plant Community Assessment.(PDF) (2015). Brenton Butterfield, Eddie Heath et al., Onterra LLC. p. 9, 12-13, 19

- Green Lake Aquatic Plant Community Assessment.(PDF) (2015). Brenton Butterfield, Eddie Heath et al., Onterra LLC. p. 9, 12-13, 19

- Marshall, Dave (December 1, 2015). "Near Shore Fishes of Green Lake" (PDF). The Nelson Institute. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- "Wisconsin's record fish program | Wisconsin DNR". dnr.wisconsin.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Green Lake Aquatic Plant Community Assessment.(PDF) (2015). Brenton Butterfield, Eddie Heath et al., Onterra LLC. p. 9, 12-13, 19

- Marshall, Dave (December 1, 2015). "Near Shore Fishes of Green Lake" (PDF). The Nelson Institute. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- Mirr, Chuck (November 17, 2014). "Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Introduction and Stocking of Landlocked Salmon into Big Green Lake" (PDF). The Nelson Institute. Retrieved November 29, 2020

- "Conservancy Properties – Green Lake Sanitary District". Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- "Green Lake Association". Green Lake Association. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- "Places to Visit in Wisconsin - Things to do in Green Lake, WI". Green Lake Area Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2020-11-18.