Sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the water (sailing ship, sailboat, windsurfer, or kitesurfer), on ice (iceboat) or on land (land yacht) over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation.

A course defined with respect to the true wind direction is called a point of sail.

Conventional sailing craft cannot derive power from sails on a point of sail that is too close to the wind. On a given point of sail, the sailor adjusts the alignment of each sail with respect to the apparent wind direction (as perceived on the craft) to mobilize the power of the wind. The forces transmitted via the sails are resisted by forces from the hull, keel, and rudder of a sailing craft, by forces from skate runners of an iceboat, or by forces from wheels of a land sailing craft to allow steering the course.

In the 21st century, most sailing represents a form of recreation or sport. Recreational sailing or yachting can be divided into racing and cruising. Cruising can include extended offshore and ocean-crossing trips, coastal sailing within sight of land, and daysailing.

Until the mid of the 19th century, sailing ships were the primary means for marine commerce; this period is known as the Age of Sail.

History

Throughout history sailing has been instrumental in the development of civilization, affording humanity greater mobility than travel overland, whether for trade, transport or warfare, and the capacity for fishing. The earliest representation of a ship under sail appears on a painted disc found in Kuwait dating between 5500 and 5000 BC. They would go selling and teaching other civilizations how to build, sail, and navigate the ships. [1] Austronesian ocean farers traveled vast distances of open ocean in outrigger canoes using navigation methods such as stick charts.[2][3] Advances in sailing technology from the Middle Ages onward enabled Arab, Chinese, Indian and European explorers to make longer voyages into regions with extreme weather and climatic conditions. There were improvements in sails, masts and rigging; improvements in marine navigation, including the cross tree and charts of both the sea and constellations, allowed more certainty in sea travel. From the 15th century onwards, European ships went further north, stayed longer on the Grand Banks and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and eventually began to explore the Pacific Northwest and the Western Arctic.[4] Sailing has contributed to many great explorations in the world.

According to Jett, the Egyptians used a bipod mast to support a sail that allowed a reed craft to travel upriver with a following wind, as late as 3500 BC. Such sails evolved into the square-sail rig that persisted up to the 19th century. Such rigs generally could not sail much closer than 80° to the wind. Fore-and-aft rigs appear to have evolved in Southeast Asia—dates are uncertain—allowing for rigs that could sail as close as 60–75° off the wind.[5]

Physics

A. Luffing (no propulsive force) — 0-30°

B. Close-hauled (lift)— 30–50°

C. Beam reach (lift)— 90°

D. Broad reach (lift–drag)— ~135°

E. Running (drag)— 180°

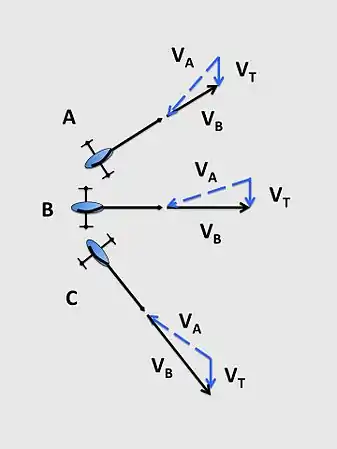

True wind (VT) is the same everywhere in the diagram, whereas boat velocity (VB) and apparent wind (VA) vary with point of sail.

The physics of sailing arises from a balance of forces between the wind powering the sailing craft as it passes over its sails and the resistance by the sailing craft against being blown off course, which is provided in the water by the keel, rudder, underwater foils and other elements of the underbody of a sailboat, on ice by the runners of an ice boat, or on land by the wheels of a sail-powered land vehicle.

Forces on sails depend on wind speed and direction and the speed and direction of the craft. The speed of the craft at a given point of sail contributes to the "apparent wind"—the wind speed and direction as measured on the moving craft. The apparent wind on the sail creates a total aerodynamic force, which may be resolved into drag—the force component in the direction of the apparent wind—and lift—the force component normal (90°) to the apparent wind. Depending on the alignment of the sail with the apparent wind (angle of attack), lift or drag may be the predominant propulsive component. Depending on the angle of attack of a set of sails with respect to the apparent wind, each sail is providing motive force to the sailing craft either from lift-dominant attached flow or drag-dominant separated flow. Additionally, sails may interact with one another to create forces that are different from the sum of the individual contributions of each sail, when used alone.

Apparent wind velocity

The term "velocity" refers both to speed and direction. As applied to wind, apparent wind velocity (VA) is the air velocity acting upon the leading edge of the most forward sail or as experienced by instrumentation or crew on a moving sailing craft. In nautical terminology, wind speeds are normally expressed in knots and wind angles in degrees. All sailing craft reach a constant forward velocity (VB) for a given true wind velocity (VT) and point of sail. The craft's point of sail affects its velocity for a given true wind velocity. Conventional sailing craft cannot derive power from the wind in a "no-go" zone that is approximately 40° to 50° away from the true wind, depending on the craft. Likewise, the directly downwind speed of all conventional sailing craft is limited to the true wind speed. As a sailboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind becomes smaller and the lateral component becomes less; boat speed is highest on the beam reach. In order to act like an airfoil, the sail on a sailboat is sheeted further out as the course is further off the wind.[6] As an iceboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind increases slightly and the boat speed is highest on the broad reach. In order to act like an airfoil, the sail on an iceboat is sheeted in for all three points of sail.[7]

Lift and drag on sails

_and_down_wind_(left).jpg.webp)

Left-hand boat: Down wind with detached air flow like a parachute— predominant drag component propels the boat with little heeling moment.

Right-hand boat: Up wind (close-hauled) with attached airflow like a wing—predominant lift component both propels the boat and contributes to heel.

Lift on a sail, acting as an airfoil, occurs in a direction perpendicular to the incident airstream (the apparent wind velocity for the headsail) and is a result of pressure differences between the windward and leeward surfaces and depends on the angle of attack, sail shape, air density, and speed of the apparent wind. The lift force results from the average pressure on the windward surface of the sail being higher than the average pressure on the leeward side.[8] These pressure differences arise in conjunction with the curved airflow. As air follows a curved path along the windward side of a sail, there is a pressure gradient perpendicular to the flow direction with higher pressure on the outside of the curve and lower pressure on the inside. To generate lift, a sail must present an "angle of attack" between the chord line of the sail and the apparent wind velocity. The angle of attack is a function of both the craft's point of sail and how the sail is adjusted with respect to the apparent wind.[9]

As the lift generated by a sail increases, so does lift-induced drag, which together with parasitic drag constitute total drag, which acts in a direction parallel to the incident airstream. This occurs as the angle of attack increases with sail trim or change of course and causes the lift coefficient to increase up to the point of aerodynamic stall along with the lift-induced drag coefficient. At the onset of stall, lift is abruptly decreased, as is lift-induced drag. Sails with the apparent wind behind them (especially going downwind) operate in a stalled condition.[10]

Lift and drag are components of the total aerodynamic force on sail, which are resisted by forces in the water (for a boat) or on the traveled surface (for an iceboat or land sailing craft). Sails act in two basic modes; under the lift-predominant mode, the sail behaves in a manner analogous to a wing with airflow attached to both surfaces; under the drag-predominant mode, the sail acts in a manner analogous to a parachute with airflow in detached flow, eddying around the sail.

Lift predominance (wing mode)

Sails allow the progress of a sailing craft to windward, thanks to their ability to generate lift (and the craft's ability to resist the lateral forces that result). Each sail configuration has a characteristic coefficient of lift and attendant coefficient of drag, which can be determined experimentally and calculated theoretically. Sailing craft orient their sails with a favorable angle of attack between the entry point of the sail and the apparent wind even as their course changes. The ability to generate lift is limited by sailing too close to the wind when no effective angle of attack is available to generate lift (causing luffing) and sailing sufficiently off the wind that the sail cannot be oriented at a favorable angle of attack to prevent the sail from stalling with flow separation.

Drag predominance (parachute mode)

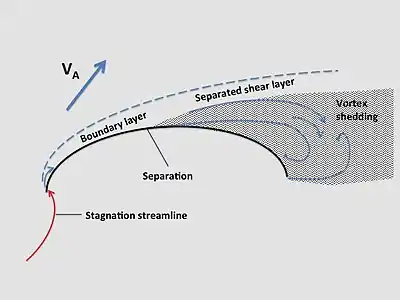

When sailing craft are on a course where the angle between the sail and the apparent wind (the angle of attack) exceeds the point of maximum lift, separation of flow occurs.[11] Drag increases and lift decreases with increasing angle of attack as the separation becomes progressively pronounced until the sail is perpendicular to the apparent wind, when lift becomes negligible and drag predominates. In addition to the sails used upwind, spinnakers provide area and curvature appropriate for sailing with separated flow on downwind points of sail, analogous to parachutes, which provide both lift and drag.[12]

- Downwind sailing with a spinnaker

Spinnaker set for a broad reach, generating both lift, with separated flow, and drag.

Spinnaker set for a broad reach, generating both lift, with separated flow, and drag. Spinnaker cross-section trimmed for a broad reach showing transition from the boundary layer to separated flow where vortex shedding commences.

Spinnaker cross-section trimmed for a broad reach showing transition from the boundary layer to separated flow where vortex shedding commences. Symmetric spinnaker while running downwind, primarily generating drag.

Symmetric spinnaker while running downwind, primarily generating drag. Symmetric spinnaker cross-section with following apparent wind, showing vortex shedding.

Symmetric spinnaker cross-section with following apparent wind, showing vortex shedding.

Wind variation with height and time

Wind speed increases with height above the surface; at the same time, wind speed may vary over short periods of time as gusts.

Wind shear affects sailing craft in motion by presenting a different wind speed and direction at different heights along the mast. Wind shear occurs because of friction above a water surface slowing the flow of air.[13] The ratio of wind at the surface to wind at a height above the surface varies by a power law with an exponent of 0.11-0.13 over the ocean. This means that a 5 m/s (9.7 kn) wind at 3 m above the water would be approximately 6 m/s (12 kn) at 15 m (50 ft) above the water. In hurricane-force winds with 40 m/s (78 kn) at the surface the speed at 15 m (50 ft) would be 49 m/s (95 kn).[14] This suggests that sails that reach higher above the surface can be subject to stronger wind forces that move the centre of effort on them higher above the surface and increase the heeling moment. Additionally, apparent wind direction moves aft with height above water, which may necessitate a corresponding twist in the shape of the sail to achieve attached flow with height.[15]

Gusts may be predicted by the same value that serves as an exponent for wind shear, serving as a gust factor. So, one can expect gusts to be about 1.5 times stronger than the prevailing wind speed (a 10-knot wind might gust up to 15 knots). This, combined with changes in wind direction suggest the degree to which a sailing craft must adjust sail angle to wind gusts on a given course.[16]

Point of sail

A sailing craft's ability to derive power from the wind depends on the point of sail it is on—the direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface. The principal points of sail roughly correspond to 45° segments of a circle, starting with 0° directly into the wind. For many sailing craft, 45° on either side of the wind is a "no-go" zone,[17] where a sail is unable to mobilize power from the wind.[7] Sailing on a course as close to the wind as possible—approximately 45°—is termed "close-hauled". At 90° off the wind, a craft is on a "beam reach". At 135° off the wind, a craft is on a "broad reach". At 180° off the wind (sailing in the same direction as the wind), a craft is "running downwind".

In points of sail that range from close-hauled to a broad reach, sails act substantially like a wing, with lift predominantly propelling the craft. In points of sail from a broad reach to down wind, sails act substantially like a parachute, with drag predominantly propelling the craft. For craft with little forward resistance ice boats and land yachts, this transition occurs further off the wind than for sailboats and sailing ships.[7]

Wind direction for points of sail always refers to the true wind—the wind felt by a stationary observer. The apparent wind—the wind felt by an observer on a moving sailing craft—determines the motive power for sailing craft.

- A sailboat on three points of sail

The waves give an indication of the true wind direction. The pennant (Canadian flag) gives an indication of apparent wind direction.

Close-hauled: the pennant is streaming backwards, the sails are sheeted in tightly.

Close-hauled: the pennant is streaming backwards, the sails are sheeted in tightly. Reaching: the pennant is streaming slightly to the side as the sails are sheeted to align with the apparent wind.

Reaching: the pennant is streaming slightly to the side as the sails are sheeted to align with the apparent wind. Running: the wind is coming from behind the vessel; the sails are "wing and wing" to be at right angles to the apparent wind.

Running: the wind is coming from behind the vessel; the sails are "wing and wing" to be at right angles to the apparent wind.

Effect on apparent wind

True wind velocity (VT) combines with the sailing craft's velocity (VB) to be the apparent wind velocity (VA), the air velocity experienced by instrumentation or crew on a moving sailing craft. Apparent wind velocity provides the motive power for the sails on any given point of sail. It varies from being the true wind velocity of a stopped craft in irons in the no-go zone to being faster than the true wind speed as the sailing craft's velocity adds to the true windspeed on a reach, to diminishing towards zero, as a sailing craft sails dead downwind.[6]

- Effect of apparent wind on sailing craft at three points of sail

Sailing craft A is close-hauled. Sailing craft B is on a beam reach. Sailing craft C is on a broad reach.

Boat velocity (in black) generates an equal and opposite apparent wind component (not shown), which adds to the true wind to become apparent wind.

Apparent wind and forces on a sailboat.

Apparent wind and forces on a sailboat.

As the boat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind becomes smaller and the lateral component becomes less; boat speed is highest on the beam reach. Apparent wind on an iceboat.

Apparent wind on an iceboat.

As the iceboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind increases slightly and the boat speed is highest on the broad reach. The sail is sheeted in for all three points of sail.[7]

The speed of sailboats through the water is limited by the resistance that results from hull drag in the water. Ice boats typically have the least resistance to forward motion of any sailing craft.[7] Consequently, a sailboat experiences a wider range of apparent wind angles than does an ice boat, whose speed is typically great enough to have the apparent wind coming from a few degrees to one side of its course, necessitating sailing with the sail sheeted in for most points of sail. On conventional sailboats, the sails are set to create lift for those points of sail where it's possible to align the leading edge of the sail with the apparent wind.[6]

For a sailboat, point of sail affects lateral force significantly. The higher the boat points to the wind under sail, the stronger the lateral force, which requires resistance from a keel or other underwater foils, including daggerboard, centerboard, skeg, and rudder. Lateral force also induces heeling in a sailboat, which requires resistance by weight of ballast from the crew or the boat itself and by the shape of the boat, especially with a catamaran. As the boat points off the wind, lateral force and the forces required to resist it become less important.[18] On ice boats, lateral forces are countered by the lateral resistance of the blades on ice and their distance apart, which generally prevents heeling.[19]

Course under sail

Wind and currents are important factors to plan on for both offshore and inshore sailing. Predicting the availability, strength and direction of the wind is key to using its power along the desired course. Ocean currents, tides and river currents may deflect a sailing vessel from its desired course.[20]

If the desired course is within the no-go zone, then the sailing craft must follow a zig-zag route into the wind to reach its waypoint or destination. Downwind, certain high-performance sailing craft can reach the destination more quickly by following a zig-zag route on a series of broad reaches.

Negotiating obstructions or a channel may also require a change of direction with respect to the wind, necessitating changing of tack with the wind on the opposite side of the craft, from before.

Changing tack is called tacking when the wind crosses over the bow of the craft as it turns and jibing (or gybing) if the wind passes over the stern.

Wind and currents

Winds and oceanic currents are both the result of the sun powering their respective fluid media. Wind powers the sailing craft and the ocean bears the craft on its course, as currents may alter the course of a sailing vessel on the ocean or a river.

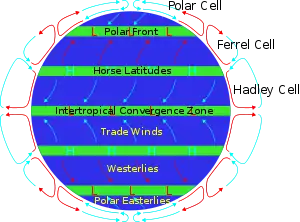

- Wind – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take atmospheric circulation into account, which causes zones of westerlies, easterlies, trade winds and high-pressure zones with light winds, sometimes called horse latitudes, in between.[21] Sailors predict wind direction and strength with knowledge of high- and low-pressure areas, and the weather fronts that accompany them. Along coastal areas, sailors contend with diurnal changes in wind direction—flowing off the shore at night and onto the shore during the day.[22] Local temporary wind shifts are called lifts, when they improve the sailing craft's ability travel along its rhumb line in the direction of the next waypoint. Unfavorable wind shifts are called headers.[23]

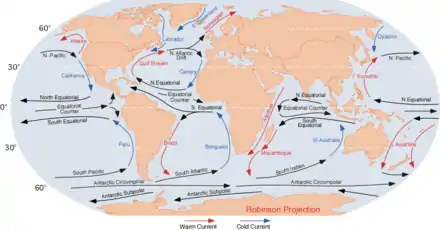

- Currents – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take major ocean current circulation into account.[24] Major oceanic currents, like the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean and the Kuroshio Current in the Pacific Ocean require planning for the effect that they will have on a transiting vessel's track. Likewise, tides affect a vessel's track, especially in areas with large tidal ranges,[25] like the Bay of Fundy or along Southeast Alaska, or where the tide flows through straits, like Deception Pass in Puget Sound.[26] Mariners use tide and current tables to inform their navigation.[20] Before the advent of motors, it was advantageous for sailing vessels to enter or leave port or to pass through a strait with the tide.[27]

Upwind

A sailing craft can sail on a course anywhere outside of its no-go zone.[28] If the next waypoint or destination is within the arc defined by the no-go zone from the craft's current position, then it must perform a series of tacking maneuvers to get there on a dog-legged route, called beating to windward.[25] The progress along that route is called the course made good; the speed between the starting and ending points of the route is called the speed made good and is calculated by the distance between the two points, divided by the travel time.[29] The limiting line to the waypoint that allows the sailing vessel to leave it to leeward is called the layline.[30] Whereas some Bermuda-rigged sailing yachts can sail as close as 30° to the wind,[29] most 20th-Century square riggers are limited to 60° off the wind.[27] Fore-and-aft rigs are designed to operate with the wind on either side, whereas square rigs and kites are designed to have the wind come from one side of the sail only.

Because the lateral wind forces are highest on a sailing vessel, close-hauled and beating to windward, the resisting water forces around the vessel's keel, centerboard, rudder and other foils is also highest to mitigate leeway—the vessel sliding to leeward of its course. Ice boats and land yachts minimize lateral motion with sidewise resistance from their blades or wheels.[31]

- Tacking and beating to windward

Tacking from starboard tack to port tack. Wind shown in red. ① on starboard tack, ② turning to windward to begin the tacking maneuver, ③ headed into the wind; the sail loses propulsion and the craft continues on momentum, ④ resuming wind power on the new port tack by sheeting in the sail, ⑤ on port tack.

Tacking from starboard tack to port tack. Wind shown in red. ① on starboard tack, ② turning to windward to begin the tacking maneuver, ③ headed into the wind; the sail loses propulsion and the craft continues on momentum, ④ resuming wind power on the new port tack by sheeting in the sail, ⑤ on port tack. Beating to windward with tacking points shown from starboard to port tack at points 1. and 3. and in reverse at point 2.

Beating to windward with tacking points shown from starboard to port tack at points 1. and 3. and in reverse at point 2.

Changing tack by tacking

Tacking or coming about is a maneuver by which a sailing craft turns its bow into and through the wind (called the "eye of the wind") so that the apparent wind changes from one side to the other, allowing progress on the opposite tack.[32] The type of sailing rig dictates the procedures and constraints on achieving a tacking maneuver. Fore-and-aft rigs allow their sails to hang limp as they tack; square rigs must present the full frontal area of the sail to the wind, when changing from side to side; and windsurfers have flexibly pivoting and fully rotating masts that get flipped from side to side.

Downwind

A sailing craft can travel directly downwind only at a speed that is less than the wind speed. However, a variety of sailing craft can achieve a higher downwind velocity made good by traveling on a series of broad reaches, punctuated by jibes in between. This is true of iceboats and sand yachts. On the water it was explored by sailing vessels, starting in 1975, and now extends to high-performance skiffs, catamarans and foiling sailboats.[33]

Navigating a channel or a downwind course among obstructions may necessitate changes in direction that require a change of tack, accomplished with a jibe.

Changing tack by jibing

Jibing or gybing is a sailing maneuver by which a sailing craft turns its stern past the eye of the wind so that the apparent wind changes from one side to the other, allowing progress on the opposite tack. This maneuver can be done on smaller boats by pulling the tiller towards yourself (the opposite side of the sail).[32] As with tacking, the type of sailing rig dictates the procedures and constraints for jibing. Fore-and-aft sails with booms, gaffs, or sprits are unstable when the free endpoints into the eye of the wind and must be controlled to avoid a violent change to the other side; square rigs as they present the full area of the sail to the wind from the rear experience little change of operation from one tack to the other; and windsurfers again have flexibly pivoting and fully rotating masts that get flipped from side to side.

Sail trimming

The most basic control of the sail consists of setting its angle relative to the wind. The control line that accomplishes this is called a "sheet." If the sheet is too loose the sail will flap in the wind, an occurrence that is called "luffing." Optimum sail angle can be approximated by pulling the sheet in just so far as to make the luffing stop, or by using tell-tails – small ribbons or yarn attached each side of the sail that both stream horizontally to indicate a properly trimmed sail. Finer controls adjust the overall shape of the sail.

Two or more sails are frequently combined to maximize the smooth flow of air. The sails are adjusted to create a smooth laminar flow over the sail surfaces. This is called the "slot effect". The combined sails fit into an imaginary aerofoil outline, so that the most forward sails are more in line with the wind, whereas the more aft sails are more in line with the course followed. The combined efficiency of this sail plan is greater than the sum of each sail used in isolation.

More detailed aspects include specific control of the sail's shape, e.g.:

- reefing, or reducing the sail area in stronger wind

- altering sail shape to make it flatter in high winds

- raking the mast when going upwind (to tilt the sail towards the rear, this being more stable)

- providing sail twist to account for wind speed differential and to spill excess wind in gusty conditions

- gibbing or lowering a sail

Reducing sail (reefing)

An important safety aspect of sailing is to adjust the amount of sail to suit the wind conditions. As the wind speed increases the crew should progressively reduce the amount of sail. On a small boat with only jib and mainsail this is done by furling the jib and by partially lowering the mainsail, a process called 'reefing the main'.

Reefing means reducing the area of a sail without actually changing it for a smaller sail. Ideally, reefing does not only result in a reduced sail area but also in a lower centre of effort from the sails, reducing the heeling moment and keeping the boat more upright.

There are three common methods of reefing the mainsail:

- Slab reefing, which involves lowering the sail by about one-quarter to one-third of its full length and tightening the lower part of the sail using an outhaul or a pre-loaded reef line through a cringle at the new clew, and hook through a cringle at the new tack.

- In-mast (or on-mast) roller-reefing. This method rolls the sail up around a vertical foil either inside a slot in the mast, or affixed to the outside of the mast. It requires a mainsail with either no battens, or newly developed vertical battens.

- In-boom roller-reefing, with a horizontal foil inside the boom. This method allows for standard- or full-length horizontal battens.

Mainsail furling systems have become increasingly popular on cruising yachts, as they can be operated shorthanded and from the cockpit, in most cases. However, the sail can become jammed in the mast or boom slot if not operated correctly. Mainsail furling is almost never used while racing because it results in a less efficient sail profile. The classical slab-reefing method is the most widely used. Mainsail furling has an additional disadvantage in that its complicated gear may somewhat increase weight aloft. However, as the size of the boat increases, the benefits of mainsail roller furling increase dramatically.

An old saying goes, "Once you've realized it's time to reef, it's too late". A similar one says, "The time to reef is when you first think about it".[34]

Hull trim

Hull trim is the adjustment of a boat's loading so as to change its fore-and-aft attitude in the water. In small boats, it is done by positioning the crew. In larger boats, the weight of a person has less effect on the hull trim, but it can be adjusted by shifting gear, fuel, water, or supplies. Different hull trim efforts are required for different kinds of boats and different conditions. Here are just a few examples: In a lightweight racing dinghy like a Thistle, the hull should be kept level, on its designed water line for best performance in all conditions. In many small boats, weight too far aft can cause drag by submerging the transom, especially in light to moderate winds. Weight too far forward can cause the bow to dig into the waves. In heavy winds, a boat with its bow too low may capsize by pitching forward over its bow (pitch-pole) or dive under the waves (submarine). On a run in heavy winds, the forces on the sails tend to drive a boat's bow down, so the crew weight is moved far aft.

Heeling

When a ship or boat leans over to one side, from the action of waves or from the centrifugal force of a turn or under wind pressure or from the number of exposed topsides, it is said to 'heel'. A sailing boat that is over-canvassed and therefore heeling excessively, may sail less efficiently. This is caused by factors such as wind gusts, crew ability, the point of sail, or hull size and design.

When a vessel is subject to a heeling force (such as wind pressure), vessel buoyancy and beam of the hull will counteract the heeling force. A weighted keel provides additional means to right the boat. In some high-performance racing yachts, water ballast or the angle of a canting keel can be changed to provide additional righting force to counteract heeling. The crew may move their personal weight to the high (upwind) side of the boat, this is called hiking, which also changes the centre of gravity and produces a righting lever to reduce the degree of heeling. Incidental benefits include faster vessel speed caused by more efficient action of the hull and sails. Other options to reduce heeling include reducing exposed sail area and efficiency of the sail setting and a variant of hiking called "trapezing". This can only be done if the vessel is designed for this, as in dinghy sailing. A sailor can (usually involuntarily) try turning upwind in gusts (it is known as rounding up). This can lead to difficulties in controlling the vessel if over-canvassed. Wind can be spilled from the sails by 'sheeting out', or loosening them. The number of sails, their size, and shape can be altered. Raising the dinghy centreboard can reduce heeling by allowing more leeway.

The increasingly asymmetric underwater shape of the hull matching the increasing angle of heel may generate an increasing directional turning force into the wind. The sails' centre of effort will also increase this turning effect or force on the vessel's motion due to increasing lever effect with increased heeling which shows itself as increased human effort required to steer a straight course. Increased heeling reduces exposed sail area relative to the wind direction, so leading to an equilibrium state. As more heeling force causes more heel, weather helm may be experienced. This condition has a braking effect on the vessel but has the safety effect in that an excessively hard pressed boat will try and turn into the wind, therefore, reducing the forces on the sail. Small amounts (≤5 degrees) of weather helm are generally considered desirable because of the consequent aerofoil lift effect from the rudder. This aerofoil lift produces helpful motion to windward and the corollary of the reason why lee helm is dangerous. Lee helm, the opposite of weather helm, is generally considered to be dangerous because the vessel turns away from the wind when the helm is released, thus increasing forces on the sail at a time when the helmsperson is not in control.

Multihulls use flotation and/or weight positioned away from the centre line of the sailboat to counter the force of the wind. This is in contrast to heavy ballast that can account for up to 90% (in extreme cases like AC boats) of the weight of a monohull sailboat. In the case of a standard catamaran, there are two similarly-sized and -shaped slender hulls connected by beams, which are sometimes overlaid by a deck superstructure. Another catamaran variation is the proa. In the case of trimarans, which have an unballasted centre hull similar to a monohull, two smaller amas are situated parallel to the centre hull to resist the sideways force of the wind. The advantage of multihulled sailboats is that they do not suffer the performance penalty of having to carry heavy ballast, and their relatively lesser draft reduces the amount of drag, caused by friction and inertia when moving through the water.

One of the most common dinghy hulls in the world is the Laser hull. It was designed by Bruce Kirby in 1969 and unveiled at the New York boat show (1971). It was designed with speed and simplicity in mind. The Laser is 13 ft 10.5 in (4.229 m) long and a 12.5 ft (3.8 m) water line and 76 square feet (7.1 m2) of sail.

Terminology

Nautical terms for elements of a vessel: starboard (right-hand side), port or larboard (left-hand side), forward or fore (frontward), aft or abaft (rearward), bow (forward part of the hull), stern (aft part of the hull), beam (the widest part). Spars, supporting sails, include masts, booms, yards, gaffs and poles.[35]

Rope and lines

In most cases, rope is the term used only for raw material. Once a section of rope is designated for a particular purpose on a vessel, it generally is called a line, as in outhaul line or dock line. A very thick line is considered a cable. Lines that are attached to sails to control their shapes are called sheets, as in mainsheet. If a rope is made of wire, it maintains its rope name as in 'wire rope' halyard.

Lines (generally steel cables) that support masts are stationary and are collectively known as a vessel's standing rigging, and individually as shrouds or stays. The stay running forward from a mast to the bow is called the forestay or headstay. Stays running aft are backstays or after stays.

Moveable lines that control sails or other equipment are known collectively as a vessel's running rigging. Lines that raise sails are called halyards while those that strike them are called downhauls. Lines that adjust (trim) the sails are called sheets. These are often referred to using the name of the sail they control (such as main sheet or jib sheet). Sail trim may also be controlled with smaller lines attached to the forward section of a boom such as a cunningham; a line used to hold the boom down is called a vang, or a kicker in the United Kingdom. A topping lift is used to hold a boom up in the absence of sail tension. Guys are used to control the ends of other spars such as spinnaker poles.

Lines used to tie a boat up when alongside are called docklines, docking cables or mooring warps. In dinghies, the single line from the bow is referred to as the painter. A rode is what attaches an anchored boat to its anchor. It may be made of chain, rope, or a combination of the two.

Some lines are referred to as ropes:

- a bell rope (to ring the bell),

- a bolt rope (attached to the edge of a sail for extra strength),

- a foot rope (for sailors on square riggers to stand on while reefing or furling the sails), and

- a tiller rope (to temporarily hold the tiller and keep the boat on course).

Other terms

Walls are called bulkheads or ceilings, while the surfaces referred to as ceilings on land are called overheads or deckheads. Floors are called soles or decks. The toilet is traditionally called the head, the kitchen is the galley. When lines are tied off, this may be referred to as made fast or belayed. Sails in different sail plans have unchanging names, however. For the naming of sails, see sail-plan.

Knots and line handling

The following knots are regarded as integral to handling ropes and lines, while sailing:[36][37]

- Bowline – forms a loop at the end of a rope or line

- Cleat hitch – affixes a line to a cleat

- Clove hitch – two half hitches around a post or other object

- Figure-eight – a stopper knot

- Half hitch − a basic overhand knot around a line or object

- Reef knot − (or square knot) joins two rope ends of equal diameter

- Rolling hitch – a friction hitch to affix a line to itself or another object

- Sheet bend – joins to rope ends of unequal diameter

Lines and halyards are typically coiled neatly for stowage and reuse.[38]

Rules and regulations

Every vessel in coastal and offshore waters is subject to the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (the COLREGS). On inland waterways and lakes other similar regulations, such as CEVNI in Europe, may apply. In some sailing events, such as the Olympic Games, which are held on closed courses where no other boating is allowed, specific racing rules such as the Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS) may apply. Often, in club racing, specific club racing rules, perhaps based on RRS, may be superimposed onto the more general regulations such as COLREGS or CEVNI.

In general, regardless of the activity, every sailor must

- Maintain a proper lookout at all times

- Adjust speed to suit the conditions

- Know whether to 'stand on' or 'give way' in any close-quarters situation.[39]

The stand-on vessel must hold a steady course and speed but be prepared to take late avoiding action to prevent an actual collision if the other vessel does not do so in time. The give-way vessel must take early, positive and obvious avoiding action, without crossing ahead of the other vessel. (Rules 16–17)

- If an approaching vessel remains on a steady bearing, and the range is decreasing, then a collision is likely. (Rule 7) This can be checked with a hand-bearing compass.

- The sailing vessel on port tack[40] gives way to the sailing vessel on starboard tack[41] (Rule 12)

- If both sailing vessels are on the same tack, the windward boat gives way to the leeward one (Rule 12)

- If a vessel on port tack is unable to determine the tack of the other boat, she should be prepared to give way (Rule 12)

- An overtaking vessel must keep clear of the vessel being overtaken (Rule 13)

- Sailing vessels must give way to vessels engaged in fishing, those not under command, those restricted in their ability to maneuver and should avoid impeding the safe passage of a vessel constrained by her draft. (Rule 18)

The COLREGS go on to describe the lights to be shown by vessels underway at night or in restricted visibility. Specifically, for sailing boats, red and green sidelights and a white stern light are required, although, for vessels under 7 m (23 ft) in length, these may be substituted by a torch or white all-round lantern. (Rules 22 & 25)

Sailors are required to be aware not only of the requirements for their own boat but of all the other lights, shapes, and flags that may be shown by other vessels, such as those fishing, towing, dredging, diving, etc., as well as sound signals that may be made in restricted visibility and at close quarters, so that they can make decisions under the COLREGS in good time, should the need arise. (Rules 32–37)

In addition to the COLREGS, CEVNI and/or any specific racing rules that apply to a sailing boat, there are also

- The IALA International Association of Lighthouse Authorities standards for lateral marks, lights, signals, and buoyage and rules designed to support safe navigation.

- The SOLAS (International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea) regulations, specifically Chapter V, which became mandatory for all leisure craft users of the sea from 1 July 2002.[42] These regulations place the obligations for safety on the owners and operators of any boat including sailboats. They specify the safety equipment needed, the emergency procedures to be used appropriate to the boat's size and its sailing range, and requirements for passage planning with regard to weather and safety.

Licensing

Licensing regulations vary widely across the world. While boating on international waters does not require any license, a license may be required to operate a vessel on coastal waters or inland waters. Some jurisdictions require a license when a certain size is exceeded (e.g., a length of 20 meters), others only require licenses to pilot passenger ships, ferries or tugboats. For example, the European Union issues the International Certificate of Competence, which is required to operate pleasure craft in most inland waterways within the union. The United States, in contrast, has no licensing, but instead has voluntary certification organizations such as the American Sailing Association.[43] These US certificates are often required to charter a boat, but are not required by any federal or state law.

Competition

Sailboat racing generally fits into one of two categories:

Introduction

Sailing is a diverse sport with many pinnacles from the Olympic Games to many world championships titles to development based campaigns for the America's Cup to round the world races such as the Vendee Globe and Volvo Ocean Race.

Sailboat racing ranges from single-person dinghy racing to large boats with 10 or more crew and from small boats costing a few thousand dollars to multimillion-dollar America's Cup campaigns. The costs of participating in the high-end large boat competitions make this type of sailing one of the most expensive sports in the world. However, there are inexpensive ways to get involved in sailboat racing, such as at community sailing clubs, classes offered by local recreation organizations and in some inexpensive dinghy and small catamaran classes. Under these conditions, sailboat racing can be comparable to or less expensive than sports such as golf and skiing. Sailboat racing is one of the few sports in which people of all ages and genders can regularly compete with and against each other.

The sport of Sailboat racing is governed by the World Sailing with most racing formats using the Racing Rules of Sailing.

Competition Criteria

Sailing regattas contain events that are defined by a combination of discipline, equipment, gender, and sailor categories.

- Equipment

Common categories of equipment include the following dinghies, multihulls, keelboats sailing yacht windsurfers, kiteboarding and radio-controlled sailboats.

- Disciplines

The following are the main disciplines:

- Fleet Racing – The commonest form of competitive sailing involving boats racing around a course.[44]

- Match Racing – Two identical boats race against each other. This is one-on-one duel requires strategy and tactics. The first to cross the finish line wins.[45]

- Team Racing – Two teams each of normally three boats compete against each other. Fast-paced racing depends on excellent boat handling skills and rapid tactical decision making.[46]

- Speed Sailing – Is managed by World Speed Sailing Record Council

- Wave Riding

- Both windsurfing and kiteboarding are experimenting with new formats.

- Gender

The majority of sailing events are "open" events in which males and females compete together on equal terms either as individuals or part of a team. Sailing has had female-only World Championships since the 1970s to encourage participation and now host more than 30 such World Championship titles each year. While many mixed-gender crews have competed in open events compulsory mixed gender are now included as events in both Olympic (Nacra 17) and Paralympic (SKUD 18).

- Sailor Categories

In addition, the following categories are sometimes applied to events:

- Age

- Nationality

- Disabled Classification

- Professional Sailor Classification

Regatta

Most sailboat and yacht racing is done in coastal or inland waters. However, in terms of endurance and risk to life, ocean races such as the Volvo Ocean Race, the solo Velux 5 Oceans Race, and the non-stop solo Vendée Globe, rate as some of the most extreme and dangerous sporting events. Not only do participants compete for days with little rest, but an unexpected storm, a single equipment failure, or collision with an ice floe could result in the sailboat being disabled or sunk hundreds or thousands of miles from search and rescue.

Equipment

- Handicap

- Where boats of different types sail against each other and are scored based on their handicaps which are calculated either before the start or after the finish. Most small boat racing is class racing or handicap racing under Portsmouth Yardstick. However most yacht racing is done under handicap the two international recognised systems are IRC, ORC Club and ORCi which are used for pinnacle events ( e.g. Fastnet Race, Commodore's Cup, Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, Bermuda Race, etc.) Other empirical handicap systems are also popular for example Performance Handicap Racing Fleet (PHRF) is very common in the U.S.A.

- Class

- Where all the boats are substantially similar, and the first boat to finish wins.

Class racing can be further subdivided into measurement controlled and manufacturer controlled classes.

Manufacturer controlled classes strictly control the production and source of equipment. (e.g. 29er, Laser, Farr 40, RS Feva, Soling, etc.)

However, it is measurement controlled classes that offer the diversity in equipment. Some classes use measurement control to tightly control the boats as much as manufacturer class (e.g., 470, Contender, Star etc.)

At the other end of the extreme are the development classes which freely allow development within a defined framework. These are most commonly either formula based like the metre class or a box-rule that defines key criteria like maximum length, minimum weight, and maximum sail area. (e.g. Moth (dinghy), the A Class Catamaran, TP 52, and IMOCA 60.

Recreational sailing

Sailing for pleasure can involve short trips across a bay, day sailing, coastal cruising, and more extended offshore or 'blue-water' cruising. These trips can be singlehanded or the vessel may be manned by families or groups of friends. Sailing vessels may proceed on their own, or be part of a flotilla with other like-minded voyagers. Sailing boats may be operated by their owners, who often also gain pleasure from maintaining and modifying their craft to suit their needs and taste, or may be rented for the specific trip or cruise. A professional skipper and even crew may be hired along with the boat in some cases. People take cruises in which they crew and 'learn the ropes' aboard craft such as tall ships, classic sailing vessels, and restored working boats.

Cruising trips of several days or longer can involve a deep immersion in logistics, navigation, meteorology, local geography and history, fishing lore, sailing knowledge, general psychological coping, and serendipity. Once the boat is acquired it is not all that expensive an endeavor, often much less expensive than a normal vacation on land. It naturally develops self-reliance, responsibility, economy, and many other useful skills. Besides improving sailing skills, all the other normal needs of everyday living must also be addressed. There are work roles that can be done by everyone in the family to help contribute to an enjoyable outdoor adventure for all.

A style of casual coastal cruising called gunkholing is a popular summertime family recreational activity. It consists of taking a series of day sails to out of the way places and anchoring overnight while enjoying such activities as exploring isolated islands, swimming, fishing, etc. Many nearby local waters on rivers, bays, sounds, and coastlines can become great natural cruising grounds for this type of recreational sailing. Casual sailing trips with friends and family can become lifetime bonding experiences.

Passagemaking

Long-distance voyaging, such as that across oceans and between far-flung ports, can be considered the near-absolute province of the cruising sailboat. Most modern yachts of 25–55 feet long, propelled solely by mechanical powerplants, cannot carry the fuel sufficient for a point-to-point voyage of even 250–500 miles without needing to resupply; but a well-prepared sail-powered yacht of similar length is theoretically capable of sailing anywhere its crew is willing to guide it. Even considering that the cost benefits are offset by a much-reduced cruising speed, many people traveling distances in small boats come to appreciate the more leisurely pace and increased time spent on the water.

Since the solo circumnavigation of Joshua Slocum in the 1890s, long-distance cruising under sail has inspired thousands of otherwise normal people to explore distant seas and horizons. The important voyages of Robin Lee Graham, Eric Hiscock, Don Street[47] and others have shown that, while not strictly racing, ocean voyaging carries with it an inherent sense of competition, especially that between man and the elements.

Such a challenging enterprise requires keen knowledge of sailing in general as well as maintenance, navigation (especially celestial navigation), and often even international diplomacy (for which an entire set of protocols should be learned and practiced). But one of the great benefits of sailboat ownership is that one may at least imagine the type of adventure that the average affordable powerboat could never accomplish.

See also

- American Sail Training Association

- Boat building

- Canadian Yachting Association

- Catboat and Sloop

- Day sailer

- Dinghy racing

- Glossary of nautical terms

- High-performance sailing

- Iceboat

- Land sailing

- Marina

- Planing (boat)

- Puddle Duck Racer

- Racing Rules of Sailing

- Royal Yachting Association

- Sailing at the Summer Olympics

- Single-handed sailing

- Sportsboat

- Tacking (sailing)

- Trailer sailer

- Turtling (sailing)

- U.S. intercollegiate sailing champions

- US Sailing

- Yacht charter

Notes

- Carter, Robert (March 2006). "Boat remains and maritime trade in the Persian Gulf during the sixth and fifth millennia BC". Antiquity.

- O'Connor, Tom (September–October 2004). "Polynesians in the Southern Ocean: Occupation of the Aukland in Islands in Prehistory". New Zealand Geographic. 69 (6–8).

- Doran, Edwin Jr. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian canoe origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781585440863.

- "Transportation and Maps" in Virtual Vault, the art of the boat is an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

- Jett, Stephen C. (2017). Ancient Ocean Crossings: Reconsidering the Case for Contacts with the Pre-Columbian Americas. University of Alabama Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-8173-1939-7.

- Jobson, Gary (1990). Championship Tactics: How Anyone Can Sail Faster, Smarter, and Win Races. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 323. ISBN 978-0-312-04278-3.

- Kimball, John (2009). Physics of Sailing. CRC Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-1466502666.

- Batchelor, G.K. (1967), An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, pp. 14–15, ISBN 978-0-521-66396-0

- Klaus Weltner A comparison of explanations of the aerodynamic lifting force Am. J. Phys. 55(1), January 1987 pg 52

- Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, London: Pitman Publishing Limited, p. 638, ISBN 978-0-273-01120-0

- Collie, S. J.; Jackson, P. S.; Jackson, M.; Gerritsen; Fallow, J.B. (2006), "Two-dimensional CFD-based parametric analysis of down-wind sail designs" (PDF), The University of Auckland, retrieved 2015-04-04

- Textor, Ken (1995). The New Book of Sail Trim. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-924486-81-4.

- Deacon, E. L.; Sheppard, P. A.; Webb, E. K. (December 1956), "Wind Profiles over the Sea and the Drag at the Sea Surface", Australian Journal of Physics, 9 (4): 511, Bibcode:1956AuJPh...9..511D, doi:10.1071/PH560511

- Hsu, S. A. (January 2006). "Measurements of Overwater Gust Factor From NDBC Buoys During Hurricanes" (PDF). Louisiana State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- Zasso, A.; Fossati, F.; Viola, I. (2005), Twisted flow wind tunnel design for yacht aerodynamic studies (PDF), 4th European and African Conference on Wind Engineering, Prague, pp. 350–351

- Hsu, S. A. (April 2008). "An Overwater Relationship Between the Gust Factor and the Exponent of Power-Law Wind Profile". Mariners Weather Log. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- Cunliffe, Tom (2016). The Complete Day Skipper: Skippering with Confidence Right From the Start (5 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4729-2418-6.

- Marchaj, C. A. (2002), Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximize Sail Power (2 ed.), International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press, p. 416, ISBN 978-0071413107

- Bethwaite, Frank (2007). High Performance Sailing. Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 978-0-7136-6704-2.

- Howard, Jim; Doane, Charles J. (2000). Handbook of Offshore Cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising. p. 214. ISBN 9781574090932.

- Yochanan Kushnir (2000). "The Climate System: General Circulation and Climate Zones". Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- Ahrens, C. Donald; Henson, Robert (2015-01-01). Meteorology Today (11 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 656. ISBN 9781305480629.

- Royce, Patrick M. (2015). Royce's Sailing Illustrated. 2 (11 ed.). ProStar Publications. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-911284-07-2.

- National Ocean Service (March 25, 2008). "Surface Ocean Currents". noaa.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Cunliffe, Tom (January 1988). "The shortest route to windward". Cruising World. 14 (1): 58–64. ISSN 0098-3519.

- "2.5 Tides and Currents" (PDF). North Central Puget Sound Geographic Response Plan. Washington Department of Ecology. December 2012. pp. 2–4. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- Findlay, Gordon D. (2005). My Hand on the Tiller. AuthorHouse. p. 138. ISBN 9781456793500.

- Cunliffe, Tom (2016). The Complete Day Skipper: Skippering with Confidence Right From the Start (5 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4729-2418-6.

- Jobson, Gary (2008). Sailing Fundamentals (Revised ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4391-3678-2.

- Walker, Stuart H.; Price, Thomas C. (1991). Positioning: The Logic of Sailboat Racing. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-393-03339-7.

- Fossati, Fabio (November 1, 2009). Aero-hydrodynamics and the Performance of Sailing Yachts: The Science Behind Sailing Yachts and Their Design. Adlard Coles Nautical. p. 352. ISBN 978-1408113387.

- Keegan, John (1989). The Price of Admiralty. New York: Viking. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-670-81416-9.

- Bethwaite, Frank (2007). High Performance Sailing. Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 978-0-7136-6704-2.

- "Reefing is Important". American Sailing Association. 2016-07-16. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- Rousmaniere, John (June 1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-393-33918-5.

- Snyder, Paul. (2002). Nautical knots illustrated. Snyder, Arthur. (Rev. ed.). Camden, Me.: International Marine. ISBN 978-0-07-170890-6. OCLC 1124534665.

- Moreau, Patrick; Heron, Jean-Benoit (2018). Marine Knots : How to Tie 40 Essential Knots. New York: Harper Design. ISBN 978-0-06-279776-6. OCLC 1030579528.

- Competent Crew: Practical Course Notes. Eastleigh, Hampshire: Royal Yachting Association. 1990. pp. 32–43. ISBN 978-0-901501-35-6.

- Pearson, Malcolm (2007). Reeds Skipper's Handbook. Adlard Coles Nautical. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7136-8338-7.

- Sails set for a breeze coming from the left-hand side of the boat

- Sails set for a breeze coming from the right side of the boat

- Pearson, Malcolm (2007). Reeds Skipper's Handbook. Adlard Coles Nautical. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-7136-8338-7.

- "ASA and US-Sailing Approved Sailing Schools in the USA". EduMaritime.net.

- "Fleet Racing". Sailing.org.

- "Match Racing". Sailing.org.

- "Team Racing". Sailing.org.

- Donald M. Street Jr. (14 May 2012). "Biography – Donald M. Street Jr".

Bibliography

- "Transportation and Maps" in Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada

- Rousmaniere, John, The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Simon & Schuster, 1999

- Chapman Book of Piloting (various contributors), Hearst Corporation, 1999

- Herreshoff, Halsey (consulting editor), The Sailor's Handbook, Little Brown and Company, 1983

- Seidman, David, The Complete Sailor, International Marine, 1995

- Jobson, Gary (2008). Sailing Fundamentals (Revised ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 224. ISBN 9781439136782.

Further reading

- Rousmaniere, John (June 1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-393-33918-5.