Greek Cypriots

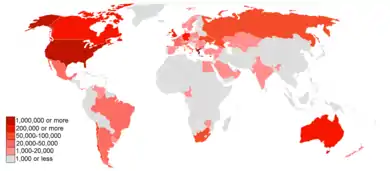

Greek Cypriots (Greek: Ελληνοκύπριοι, Turkish: Kıbrıs Rumları or Kıbrıs Yunanları) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus,[3][4][5][6] forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2011 census, 659,115 respondents recorded their ethnicity as Greek, forming almost 99% of the 667,398 Cypriot citizens and over 78% of the 840,407 total residents of the area controlled by the Republic of Cyprus.[1] These figures do not include the 29,321 citizens of Greece residing in Cyprus, ethnic Greeks recorded as citizens of other countries, or the population of Turkish-occupied northern Cyprus.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1.2 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

≈500,000 in diaspora[2] | |

| United Kingdom | 270,000 |

| Australia, South Africa, Greece, United States and others | ≈230,000 |

| Languages | |

| Modern Greek (Cypriot and standard) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Greek Orthodox) | |

The majority of Greek Cypriots are members of the Church of Cyprus, an autocephalous Greek Orthodox Church within the wider communion of Orthodox Christianity.[5][7] In regard to the 1960 Constitution of Cyprus, the term also includes Maronites, Armenians, and Catholics of the Latin Church ("Latins"), who were given the option of being included in either the Greek or Turkish communities and voted to join the former.

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Cyprus was part of the Mycenaean civilization with local production of Mycenaean vases dating to the Late Helladic III (1400–1050 BC). The quantity of this pottery concludes that there were numerous Mycenaean settlers, if not settlements, on the island.[8] Archaeological evidence shows that Greek settlement began unsystematically in c. 1400 BC, then steadied (possibly due to Dorian invaders on the mainland) with definite settlements established in c. 1200 BC.[9] The close connection between the Arcadian dialect and those of Pamphylia and Cyprus indicates that the migration came from Achaea.[10] The Achaean tribe may have been an original population of the Peloponnese, Pamphylia, and Cyprus, living in the latter prior to the Dorian invasion, and not a subsequent immigrant group; the Doric elements in Arcadian are lacking in Cypriot.[10] Achaeans settled among the old population, and founded Salamis.[11] The epic Cypria, dating to the 7th century BC, may have originated in Cyprus.[12]

Middle Ages

The Byzantine era profoundly molded Greek Cypriot culture. The Greek Orthodox Christian legacy bestowed on Greek Cypriots in this period would live on during the succeeding centuries of foreign domination. Because Cyprus was never the final goal of any external ambition, but simply fell under the domination of whichever power was dominant in the eastern Mediterranean, destroying its civilization was never a military objective or necessity.

The Cypriots did however endure the oppressive rule of first the Lusignans and then the Venetians from the 1190s through to 1570. King Amaury, who succeeded his brother Guy de Lusignan in 1194, was particularly intolerant of the Orthodox Church. Greek Cypriot land was appropriated for the Latin churches after they were established in the major towns on the island. In addition, tax collection was also part of the heavy oppressive attitude of the occupiers to the locals of the island, in that it was now being conducted by the Latin churches themselves.

Early modern period

The Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571 replaced Venetian rule. Despite the inherent oppression of foreign subjugation, the period of Ottoman rule (1570–1878) had a limited impact on Greek Cypriot culture. The Ottomans tended to administer their multicultural empire with the help of their subject millets, or religious communities. The millet system allowed the Greek Cypriot community to survive, administered on behalf of Constantinople by the Archbishop of the Church of Cyprus. Cypriot Greeks were now able to take control of the land they had been working on for centuries. Although religiously tolerant, Ottoman rule was generally harsh and inefficient. The patriarch serving the Ottoman sultan acted as ethnarch, or leader of the Greek nation, and gained secular powers as a result of the gradual dysfunction of Ottoman rule, for instance in adjudicating justice and in the collection of taxes. Turkish settlers suffered alongside their Greek Cypriot neighbors, and the two groups together endured centuries of oppressive governance from Constantinople. A minority of Greek Cypriots converted to Islam during this period, and are sometimes referred to as "neo-Muslims" by historians.[13][14]

Modern history

Politically, the concept of enosis – unification with the Greek "motherland" – became important to literate Greek Cypriots after Greece declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1821. A movement for the realization of enosis gradually formed, in which the Church of Cyprus played a dominant role during the Cyprus dispute.

Nobody could be found to eliminate it,

Nobody, for it is protected from above by my God,

Hellenism will be lost, only when the world is gone."

Archbishop Kyprianos' fictional response to Kucuk Mehmet's threat to execute the Greek Orthodox Christian bishops of Cyprus, in Vasilis Michaelides epic poem "The 9th of July of 1821 in Nicosia, Cyprus", written in 1884–1895. The poem is considered a key literary expression of Greek Cypriot Enosis sentiment.[15]

During British rule (1878–1960), the British brought an efficient colonial administration, but government and education were administered along ethnic lines, accentuating differences. For example, the education system was organized with two Boards of Education, one Greek and one Turkish, controlled by Athens and Istanbul, respectively. The resulting education emphasized linguistic, religious, cultural, and ethnic differences and ignored traditional ties between the two Cypriot communities. The two groups were encouraged to view themselves as extensions of their respective motherlands, and the development of two distinct nationalities with antagonistic loyalties was ensured.[16]

The importance of religion within the Greek Cypriot community was reinforced when the Archbishop of the Church of Cyprus, Makarios III, was elected the first president of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960. For the next decade and a half, enosis was a key issue for Greek Cypriots, and a key cause of events leading up to the 1974 coup, which prompted the Turkish invasion and occupation of the northern part of the island. Cyprus remains divided today, with the two communities almost completely separated. Many Greek Cypriots, most of whom lost their homes, lands and possessions during the Turkish invasion, emigrated mainly to the UK, USA, Australia, South Africa and Europe. There are today estimated to be 335,000 Greek Cypriot emigrants living in Great Britain. The majority of the Greek Cypriots in Great Britain currently live in England; there is an estimate of around 3,000 in Wales and 1,000 in Scotland. By the early 1990s, Greek Cypriot society enjoyed a high standard of living. Economic modernization created a more flexible and open society and caused Greek Cypriots to share the concerns and hopes of other secularized West European societies. The Republic of Cyprus joined the European Union in 2004, officially representing the entire island, but suspended for the time being in Turkish-occupied northern Cyprus.

Population

Greeks in Cyprus number 659,115, according to the 2011 Cypriot census.[1] There is a notable community of Cypriots and people of Cypriot descent in Greece. In Athens, the Greek Cypriot community numbers ca. 55,000 people.[17] There is also a large Greek Cypriot diaspora, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Diaspora

Culture

Cuisine

Cypriot cuisine, as with other Greek cuisine, was imprinted with the spices and herbs made common as a result of extensive trade links within the Ottoman Empire. Names of many dishes came to reflect the sources of the ingredients from the many lands under the Ottoman rule. Coffee houses pervasively spread throughout the island into all major towns and countless villages.

Language

The everyday language of Greek Cypriots is Cypriot Greek, a dialect of Modern Greek. It shares certain characteristics with varieties of Crete, the Dodecanese and Chios, as well as those of Asia Minor.

Greek Cypriots are generally educated in Standard Modern Greek, though they tend to speak it with an accent and preserve some Cypriot Greek grammar.

Notable people

_Cyprus.jpg.webp)

Ancient

- Acesas, Salaminian weaver

- Antiochus Gelotopoios, admiral in the fleet of Alexander the Great

- Apollodorus, Kitian physician

- Apollonios of Kition, 1st century BCE physician of the Empiric school

- Clearchus of Soli, 4th–3rd century BCE Peripatetic philosopher

- Demonax, 2nd CE Cynic philosopher

- Evagoras I, king of Salamis 411–374 BCE

- Evagoras II, king of Salamis 361–351 BCE

- Nicocles, king of Paphos

- Nicocles, king of Salamis 374/3–361 BC

- Nikokreon, king of Salamis

- Onesilus, king of Salamis 499–497 BC

- Paeon of Amathus, Hellenistic historian

- Persaeus, 3rd century BCE Stoic philosopher, student of Zeno

- Pnytagoras, king of Salamis

- Stasanor, 4th century BCE general of Alexander the Great

- Stasinos, poet, author of the epic poem Cypria

- Synnesis of Cyprus, 4th century BCE physician

- Zeno of Citium, 3rd century BCE philosopher, founder of the Stoic school of philosophy

- Zeno of Cyprus, 4th century CE physician

Medieval

- Epiphanius of Salamis, 4th century Bishop of Salamis

- Saint Spyridon, 4th century Bishop of Trimythous

- Saint Tychon, 4th century Bishop of Amathus

- Theodora, 6th century empress of the Eastern Roman Empire

- John the Merciful, 7th century Amathusian Patriatch of Alexandria

- Neophytos of Cyprus, 13th century monk

- Leontios Machairas, 15th century historian

- Georgios Boustronios, 15th century historian

- Ioannis Kigalas, 17th century scholar and professor

Modern

- Cat Stevens, Greek Cypriot father

- Alkinoos Ioannidis, musician, born in Nicosia

- Anna Vissi, singer, born in Larnaca

- Aristos Petrou, Cypriot-American rapper, one half of the rap duo Suicideboys

- Christopher A. Pissarides, Cypriot economist, Nobel laureate, born in Nicosia

- Demetri Catrakilis, South African rugby union player

- George Kallis, Composer

- George Michael, English singer-songwriter, Greek Cypriot father

- George Eugeniou, founder and Artistic Director of Art Theatre, London

- Georgios Grivas, military officer

- George Young, Greek Cypriot mother

- Grigoris Afxentiou, guerrilla fighter

- Kypros Nicolaides, Professor in Fetal Medicine at King's College Hospital, London

- Kyriakos Charalambides

- Lambros Lambrou (footballer)

- Lambros Lambrou (skier)

- Makarios III, first President of Cyprus

- Marcos Baghdatis, tennis player

- Michael Cacoyannis, cinema director

- Michael Christos Kashalos[18]

- Michalis Hatzigiannis, singer

- Michael Mili[19]

- Mick Karn, musician

- Mihalis Violaris, singer

- Nico Yennaris

- Andreas G. Orphanides, Professor, Rector

- Paul Stassino

- Sotiris Moustakas, actor

- Stelios Haji-Ioannou, entrepreneur

- Stel Pavlou, English writer, Greek Cypriot father

- Theo Paphitis

- Costas Liassides, British Cypriot entrepreneur

- Tio Ellinas

- Tonia Buxton

- Vasilis Michaelides, poet

- Vassilis Hatzipanagis, football player

- Andros Townsend's mother

- Roys Poyiadjis

- Grigoris Kastanos

- Demis Hassabis, artificial intelligence researcher, Greek Cypriot father

- Jamie Demetriou, comedian, actor, screenwriter

- Natasia Demetriou, comedian, actor, screenwriter

See also

References

- "Population – Country of Birth, Citizenship Category, Country of Citizenship, Language, Religion, Ethnic/Religious Group, 2011". Statistical Service of the Republic of Cyprus. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Papadakis, Yiannis (2011), "Cypriots, Greek", in Cole, Jeffrey E. (ed.), Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, p. 92, ISBN 978-1-59884-302-6,

The population of Greek Cypriots currently living in Cyprus is around 650,000. In addition, it is estimated that up to 500,000 Greek Cypriots live outside Cyprus, the major concentrations being in the United Kingdom (270,000), Australia, South Africa, Greece, and the United States.

- "The Constitution – Appendix D: Part 01 – General Provisions". Constitution of Cyprus. Republic of Cyprus. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "About Cyprus – History – Modern Times". Government Web Portal – Areas of Interest. Government of Cyprus. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Solsten, Eric (January 1991). "A Country Study: Cyprus". Federal Research Division. Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "The Orthodox Church of Cyprus". Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Archived from the original on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "About Cyprus – Towns and Population". Government Web Portal – Areas of Interest. Government of Cyprus. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- V. R. d'A. Desborough (5 February 2007). The Last Mycenaeans and Their Successors: An Archaeological Survey, c.1200 – c.1000 B.C. Wipf & Stock Publ. pp. 196–. ISBN 978-1-55635-201-0.

- George Hill (23 September 2010). A History of Cyprus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-108-02062-6.

- Hill 2010, p. 85.

- Hill 2010, pp. 85–86.

- Hill 2010, pp. 90–93.

- Peter Alford Andrews, Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1989, ISBN 3-89500-297-6

- Savile, Albany Robert, Cyprus, 1878, p. 130

- "Η 9η Ιουλίου του 1821 εν Λευκωσία Κύπρου – Βασίλης Μιχαηλίδης". ςww.apotipomata.com. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Xypolia, Ilia (2011). "Cypriot Muslims among Ottomans, Turks and Two World Wars". Bogazici Journal. 25 (2): 109–120. doi:10.21773/boun.25.2.6.

- Madianou 2012, p. 41.

- 1885–1974., Kasialos, Michaēl Chr. (2000). Michaēl Chr. Kasialos : hē krymmenē goēteia tēs zōgraphikēs = Michael Chr. Kashalos : the hidden fascination of painting. Dēmotikē Pinakothēkē Larnakas. [Larnaka]: Dēmos Larnakas. ISBN 996360322X. OCLC 45757568.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Mili, Michael (2012). Cigarette Money. USA: Amazon. p. 260. ISBN 978-1481065887.

Sources

- Mirca Madianou (12 November 2012). Mediating the Nation. Routledge. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-136-61105-6.

- Quataert, Donald The Ottoman Empire 1700–1922 Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-83910-6

- Winbladh, M.-L., The Origins of The Cypriots. With Scientific Data of Archaeology and Genetics, Galeri Kultur Publishing, Lefkoşa 2020

External links

- Reassessing what we collect website – Greek Cypriot London History of Greek Cypriot London with objects and images

- Cyprus: Historical Setting