Gorgon

A Gorgon (/ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ Gorgon/Gorgo) is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the term most commonly refers to three sisters who are described as having hair made of living, venomous snakes and horrifying visages that turned those who beheld them to stone. Traditionally, two of the Gorgons, Stheno and Euryale, were immortal, but their sister Medusa was not and was slain by the demigod and hero Perseus.

| Greek mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

|

|

Etymology

The name derives from the ancient Greek word γοργός gorgós, which means "grim, dreadful", and appears to come from the same root as the Sanskrit: गर्जन, garjana, which is defined as a guttural sound, similar to the growling of a beast,[1] thus possibly originating as an onomatopoeia.

Depictions

Gorgons were a popular image in Greek mythology, appearing in the earliest of written records of Ancient Greek religious beliefs such as those of Homer, which may date to as early as 1194–1184 BC. Because of their legendary and powerful gaze that could turn one to stone, images of the Gorgons were put upon objects and buildings for protection. An image of a Gorgon holds the primary location at the pediment of the temple at Corfu, which is the oldest stone pediment in Greece, and is dated to c. 600 BC.

A marble statue 1.35 m high of a Gorgon, dating from the 6th century BC, was found almost intact in 1993, in an ancient public building in Parikia, Paros capital, Greece (Archaeological Museum of Paros no. 1285, see pictures below). It is thought to have originally belonged to a temple.

The concept of the Gorgon is at least as old in classical Greek mythology as Perseus and Zeus. The name is Greek, being derived from "gorgos" and translating as terrible or dreadful. Gorgoneia (figures depicting a Gorgon head, see below) first appear in Greek art at the turn of the 8th century BC. One of the earliest representations is on an electrum stater discovered during excavations at Parium.[2] Other early eighth-century examples were found at Tiryns. Going even further back into history, there is a similar image from the Knossos palace, datable to the 15th century BC. Marija Gimbutas even argues that "the Gorgon extends back to at least 6000 BC, as a ceramic mask from the Sesklo culture ...".[3] She also identifies the prototype of the Gorgoneion in Neolithic art motifs, especially in anthropomorphic vases and terracotta masks inlaid with gold.[4]

Pausanias (5.10.4, 8.47.5, many other places), a geographer of the 2nd century AD, supplies details of where and how gorgons were represented in Greek art and architecture.

The large Gorgon eyes, as well as Athena's "flashing" eyes, are symbols termed "the divine eyes" by Gimbutas (who did not originate the perception); they appear also in Athena's sacred bird, the little owl. They may be represented by spirals, wheels, concentric circles, swastikas, firewheels, and other images. The awkward stance of the gorgon, with arms and legs at angles is closely associated with these symbols as well.

Some Gorgons are shown with broad, round heads, serpentine locks of hair, large staring eyes, wide mouths, tongues lolling, the tusks of swine, large projecting teeth, flared nostrils, and sometimes short, coarse beards.[5] (In some cruder representations, stylized hair or blood flowing under the severed head of the Gorgon has been mistaken for a beard or wings.)

Some reptilian attributes such as a belt made of snakes and snakes emanating from the head or entwined in the hair, as in the temple of Artemis in Corfu, are symbols likely derived from the guardians closely associated with early Greek religious concepts at the centers such as Delphi where the dragon Delphyne lived and the priestess Pythia delivered oracles. The skin of the dragon was said to be made of impenetrable scales.[6]

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece Disk-fibula with a gorgoneion, bronze with repoussé decoration, second half of the 6th century BC (Louvre)

Disk-fibula with a gorgoneion, bronze with repoussé decoration, second half of the 6th century BC (Louvre) An archaic Gorgon (around 580 BC), as depicted on a pediment from the temple of Artemis in Corfu, on display at the Archaeological Museum of Corfu

An archaic Gorgon (around 580 BC), as depicted on a pediment from the temple of Artemis in Corfu, on display at the Archaeological Museum of Corfu

Origins

A number of early classics scholars interpreted the myth of the Medusa as a quasi-historical, or "sublimated", memory of an actual invasion.[7][lower-alpha 1]

The legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that "the Hellenes overran the goddess's chief shrines" and "stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks", the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane.

That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind.

— J. Campbell (1968)[9][lower-alpha 2]

While seeking origins others have suggested examination of some similarities to the Babylonian creature, Humbaba, in the Gilgamesh epic.

Classical tradition

Transitions in religious traditions over such long periods of time may make some strange turns. Gorgons are often depicted as having wings, brazen claws, the tusks of boars, and scaly skin. The oldest oracles were said to be protected by serpents and a Gorgon image was often associated with those temples. Lionesses or sphinxes are frequently associated with the Gorgon as well. The powerful image of the Gorgon was adopted for the classical images and myths of Athena and Zeus, perhaps being worn in continuation of a more ancient religious imagery. In late myths, the Gorgons were said to be the daughters of two sea deities: Keto, the sea monster, and Phorcys, her brother-husband.

Homer, the author of the oldest known work of European literature, speaks only of one Gorgon, whose head is represented in the Iliad as fixed in the centre of the aegis of Athena:

About her shoulders she flung the tasselled aegis, fraught with terror ... and therein is the head of the dread monster, the Gorgon, dread and awful ...[10](5.735ff)

Its earthly counterpart is a device on the shield of Agamemnon:

... and therein was set as a crown the Gorgon, grim of aspect, glaring terribly, and about her were Terror and Rout.[10](11.35ff)

In the Odyssey, the Gorgon is a monster of the underworld into which the earliest Greek deities were cast:

... and pale fear seized me, lest august Persephone might send forth upon me from out of the house of Hades the head of the Gorgon, that awful monster ...[11](11.635)

Around 700 BC, Hesiod,[13] imagines the Gorgons as sea daemons and increases the number of them to three – Stheno (the mighty), Euryale (the far-springer, or of the wide sea), and Medusa (the queen), and makes them the daughters of the sea deities Keto and Phorcys. Their home is on the farthest side of the western ocean; according to later authorities, in Libya. Ancient Libya is identified as a possible source of the deity, Neith, who also was a creation deity in Ancient Egypt and, when the Greeks occupied Egypt, they said that Neith was called Athene in Greece.

Of the three Gorgons in classical Greek mythology, only Medusa is mortal.

The Attic tradition, reproduced in Euripides (Ion), regarded the Gorgon as a monster, produced by Gaia to aid her children, the Titans, against the new Olympian deities. Classical interpretations suggest that Gorgon was slain by Athena, who wore her skin thereafter.

The Bibliotheca[14] provides a good summary of the Gorgon myth. Much later stories claim that each of three Gorgon sisters, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, had snakes for hair, and that they had the power to turn anyone who looked at them to stone. According to Ovid,[15] a Roman poet writing in 8 AD, who was noted for accuracy regarding the Greek myths, Medusa alone had serpents in her hair, and he explained that this was due to Athena (Roman Minerva) cursing her. Medusa had copulated with Poseidon (Roman Neptune) in a temple of Athena after he was aroused by the golden color of Medusa's hair. Athena therefore changed the enticing golden locks into serpents.

Virgil mentions that the Gorgons lived in the entrance of the Underworld.[16] Diodorus and Palaephatus mention that the Gorgons lived in the Gorgades, islands in the Aethiopian Sea. The main island was called Cerna. Henry T. Riley suggests these islands may correspond to Cape Verde.[15]

According to Pseudo-Hyginus the "Gorgo Aix" (Γοργώ Aιξ), daughter of Helios, was killed by Zeus during the Titanomachy. From her skin, a goat-like hide rimmed with serpents, he made his famous aegis, and placed her fearsome visage upon it. This he gave to Athena. Then Aix became the goat Capra (Greek: Aix), on the left shoulder of the constellation Auriga.[17] A primeval Gorgon was sometimes said to be the father of Medusa and her sister Gorgons by the sea Goddess Ceto. This figure may have been the same as Gorgo Aix as the primal Gorgon was of an indeterminable gender.

An Amazon with her shield bearing the Gorgon head image. Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 510–500 BC

An Amazon with her shield bearing the Gorgon head image. Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 510–500 BC The aegis on the Lemnian Athena of Phidias, represented by a cast at the Pushkin Museum

The aegis on the Lemnian Athena of Phidias, represented by a cast at the Pushkin Museum First century BC mosaic of Alexander the Great bearing on his armor an image of the Gorgon as an aegis (Naples National Archaeological Museum)

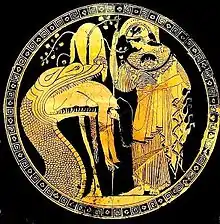

First century BC mosaic of Alexander the Great bearing on his armor an image of the Gorgon as an aegis (Naples National Archaeological Museum) Athena wears the ancient form of the Gorgon head on her aegis, as the huge serpent who guards the golden fleece regurgitates Jason; cup by Douris, Classical Greece, early fifth century BC (Vatican Museum)

Athena wears the ancient form of the Gorgon head on her aegis, as the huge serpent who guards the golden fleece regurgitates Jason; cup by Douris, Classical Greece, early fifth century BC (Vatican Museum)

Perseus and Medusa

In late myths, Medusa was the only one of the three Gorgons who was not immortal. King Polydectes sent Perseus to kill Medusa in hopes of getting him out of the way, while he pursued Perseus's mother, Danae. Some of these myths relate that Perseus was armed with a scythe from Hermes and a mirror (or a shield) from Athena. Perseus could safely cut off Medusa's head without turning to stone by looking only at her reflection in the shield. From the blood that spurted from her neck and falling into the sea, sprang Pegasus and Chrysaor, her sons by Poseidon. Other sources say that each drop of blood became a snake. Perseus is said by some to have given the head, which retained the power of turning into stone all who looked upon it, to Athena. She then placed it on the mirrored shield called Aegis and she gave it to Zeus. Another source says that Perseus buried the head in the marketplace of Argos.

According to other accounts, either he or Athena used the head to turn Atlas into stone, transforming him into the Atlas Mountains that held up both heaven and earth.[18][15](4.627) He also used the Gorgon against Cetus (when saving Andromeda) and a competing suitor, Phineas, Andromeda's cousin. Ultimately, he used her against King Polydectes. When Perseus returned to the court of the king, Polydectes asked if he had the head of Medusa. Perseus replied "here it is" and held it aloft, turning the whole court to stone.

Protective and healing powers

In Ancient Greece a Gorgoneion (a stone head, engraving, or drawing of a Gorgon face, often with snakes protruding wildly and the tongue sticking out between her fangs) frequently was used as an apotropaic symbol[19] and placed on doors, walls, floors, coins, shields, breastplates, and tombstones in the hopes of warding off evil. In this regard Gorgoneia are similar to the sometimes grotesque faces on Chinese soldiers’ shields, also used generally as an amulet, a protection against the evil eye. Likewise, in Hindu mythology, Kali is often shown with a protruding tongue and snakes around her head.

In some Greek myths, blood taken from the right side of a Gorgon could bring the dead back to life, yet blood taken from the left side was an instantly fatal poison. Athena gave a vial of the healing blood to Asclepius, which ultimately brought about his demise.

Heracles is said to have obtained a lock of Medusa’s hair (which possessed the same powers as the head) from Athena and to have given it to Sterope, the daughter of Cepheus, as a protection for the town of Tegea against attack. According to the later idea of Medusa as a beautiful maiden, whose hair had been changed into snakes by Athena, the head was represented in works of art with a wonderfully handsome face, wrapped in the calm repose of death.

Cultural depictions of Gorgons

Gorgons, especially Medusa, have become a common image and symbol in Western culture since their origins in Greek mythology, appearing in art, literature, and elsewhere throughout history. In A Tale of Two Cities, for example, Charles Dickens compares the exploitative French aristocracy to "the Gorgon" — he devotes an entire chapter to this extended metaphor.

Genealogy

See also

Notes

- A large part of Greek myth is politico-religious history. Bellerophon masters winged Pegasus and kills the Chimaera. Perseus, in a variant of the same legend, flies through the air and beheads Pegasus’s mother, the Gorgon Medusa; much as Marduk, a Babylonian hero, kills the she-monster Tiamat, Goddess of the Seal. Perseus’s name should properly be spelled Perseus, ‘the destroyer’; and he was not, as Professor Kerenyi has suggested, an archetypal Death-figure but, probably, represented the patriarchal Hellenes who invaded Greece and Asia Minor early in the second millennium BC, and challenged the power of the Triple-goddess. Pegasus had been sacred to her because the horse with its moon-shaped hooves figured in the rain-making ceremonies and the installment of sacred kings; his wings were symbolical of a celestial nature, rather than speed. Jane Harrison has pointed out[7] that Medusa was once the goddess herself, hiding behind a prophylactic Gorgon mask: A hideous face intended to warn the profane against trespassing on her Mysteries. Perseus beheads Medusa: that is, the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines, stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks, and took possession of the sacred horses – an early representation of the goddess with a Gorgon’s head and a mare’s body has been found in Boeotia. Bellerophon, Perseus’s double, kills the Lycian Chimaera, that is: The Hellenes annulled the ancient Medusan calendar, and replaced it with another.

— R. Graves (1955)[8] - We have already spoken of Medusa and of the powers of her blood to render both life and death. We may now think of the legend of her slayer, Perseus, by whom her head was removed and presented to Athene. Professor Hainmond assigns the historical King Perseus of Mycenae to a date c. 1290 B.C., as the founder of a dynasty; and Robert Graves – whose two volumes on The Greek Myths are particularly noteworthy for their suggestive historical applications – proposes that the legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that "the Hellenes overran the goddess's chief shrines" and "stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks", the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane. That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind. And in every such screening myth – in every such mythology (that of the Bible being, as we have just seen, another of the kind) – there enters in an essential duplicity, the consequences of which cannot be disregarded or suppressed.

— J. Campbell (1968)[9] - There are two major conflicting stories for Aphrodite's origins: Hesiod[12] claims that she was "born" from the foam of the sea after Cronus castrated Uranus, thus making her Uranus' daughter; but Homer[10](Book V) has Aphrodite as daughter of Zeus and Dione. According to Plato,[20] the two were entirely separate entities: Aphrodite Ourania and Aphrodite Pandemos.

- Homer names Thoosa as a daughter of Phorcys, without specifying her mother.[11](1.70–73)

- Most sources describe Medusa as the daughter of Phorcys and Ceto, though the author Hyginus (Fabulae Preface) makes Medusa the daughter of Gorgon and Ceto.

References

- Feldman, Thalia (1965). "Gorgo and the origins of fear". Arion. 4 (3): 484–94. JSTOR 20162978.

- Potts, Albert A. (1982). The World's Eye. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 26–28. ISBN 0-8131-1387-3.

- Gimbutas, Marija A. (2001). The Living Goddesses. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-22915-0.

- Gimbutas, Marija A.; Campbell, Joseph (1 October 1989). Language of the Goddess. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0062503565.

- Wilk, Stephen R. (26 June 2000). Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988773-6.

- Lemprière, John (1833). "Gorgones". Bibliotheca classica: or, A classical dictionary: [...]. G. & C. & H. Carvill. p. 620.

impenetrable scales

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (5 June 1991) [1908]. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0691015149.

- Graves, Robert (1955). The Greek Myths. Penguin Books. pp. 17, 244. ISBN 978-0241952740.

- Campbell, Joseph (1968). Occidental Mythology. The Masks of God. 3. Penguin Books. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0140194418.

- Homer. Iliad.

- Homer. Odyssey.

- Hesiod. Theogony.

- "Shield of Heracles" in Theogony[12](270)

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca. 2.2.6, 2.4.1, 2.4.2.

- Ovid. The Metamorphoses. commented by Henry T. Riley. ISBN 978-1-4209-3395-6.

- Virgil. Aeneid.

- Pseudo-Hyginus. Astronomica. Translated by Grant. 2.13.

- Polyeidos. Fragment 837.

- Garber, Marjorie (24 February 2003). "Introduction". The Medusa Reader. p. 2. ISBN 0-415-90099-9.

- Plato. Symposium. 180e.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gorgon, Gorgons". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 257.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gorgon, Gorgons". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 257.- Additional material has been added from the 1824 Lemprière's Classical Dictionary.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gorgons. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |