George H. Steuart (brigadier general)

George Hume Steuart (August 24, 1828 – November 22, 1903) was a planter in Maryland and an American military officer; he served thirteen years in the United States Army before resigning his commission at the start of the American Civil War. He joined the Confederacy and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Army of Northern Virginia. Nicknamed "Maryland" to avoid verbal confusion with Virginia cavalryman J.E.B. Stuart, Steuart unsuccessfully promoted the secession of Maryland before and during the conflict. He began the war as a captain of the 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA, and was promoted to colonel after the First Battle of Manassas.

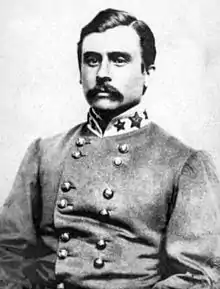

George Hume Steuart | |

|---|---|

Brigadier General George H. Steuart in Confederate uniform | |

| Nickname(s) | "Maryland Steuart" |

| Born | August 24, 1828 Baltimore, Maryland |

| Died | November 22, 1903 (aged 75) South River, Maryland |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1848–61 (USA), 1861–65 (CSA) |

| Rank | Brigadier General CSA |

| Commands held | Maryland Brigade, Army of Northern Virginia |

| Battles/wars | Utah War |

| Relations | George H. Steuart (great-grandfather) George H. Steuart (father) Richard Sprigg Steuart (uncle) |

In 1862 he became brigadier general. After a brief cavalry command he was reassigned to infantry. Wounded at Cross Keys, Steuart was out of the war for almost a year while recovering from a shoulder injury. He was reassigned to Lee's army shortly before the Battle of Gettysburg. Steuart was captured at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, and exchanged in the summer of 1864. He held a command in the Army of Northern Virginia for the remainder of the war. Steuart was among the officers with Robert E. Lee when he surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House.

Steuart spent the rest of a long life operating a plantation in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. In the late nineteenth century, he joined the United Confederate Veterans and became commander of the Maryland division.

Early life

George Hume Steuart was born on August 24, 1828 into a family of Scottish ancestry in Baltimore. The eldest of nine children,[1] he was raised at his family's estate in West Baltimore, known as Maryland Square, located near the present-day intersection of Baltimore and Monroe Streets. The Steuart family were wealthy plantation owners and were opposed to the abolition of slavery.

The Steuarts shared a long tradition of military service. He was the son of Major General George H. Steuart, of Anne Arundel County, Maryland, who served in the War of 1812, and with whom he is often confused. Baltimore residents referred to the father and son as "The Old General" and "The Young General."[2] The elder Steuart inherited approximately 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of land in around 1842, including a farm at Mount Steuart, and around 150 slaves, a high number in the Upper South.[3]

Steuart was the grandson of Dr. James Steuart, a physician who served in the American Revolutionary War, and the great-grandson of Dr. George H. Steuart, a physician who emigrated to Maryland from Perthshire, Scotland, in 1721, and was lieutenant colonel of the Horse Militia under Governor Horatio Sharpe.[3]

Early military career

Steuart attended the United States Military Academy between July 1, 1844 and July 1, 1848,[4] graduating 37th in the class of 1848, aged nineteen. Steuart was assigned as 2nd lieutenant to the 2nd Dragoons, a regiment of cavalry that served in the frontier fighting Indians. He served in the Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, in 1848, carried out frontier duty at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1849, and participated in an expedition to the Rocky Mountains in 1849.[4] He actively participated in the US Army's Cheyenne expedition of 1856, the Utah War against the Mormons in 1857–1858, and the Comanche expedition of 1860.[5]

Marriage and family

He married Maria H. Kinzie, granddaughter of John Kinzie, founder of the city of Chicago, on January 14, 1858. The couple had met in Kansas and, once married, lived at Fort Leavenworth, although they were separated for long periods while Steuart was on campaign duty and stationed at distant frontier posts.[6] They had two daughters: Marie Hunter, who was born in 1860 and went on to marry one Edmund Davis, and Ann Mary, born in 1864, who married one Rudolph Aloysius Leibig (1863-1895).[7][8][9] The coming of war would place considerable strain on the Steuarts' marriage, leading to "unfortunate differences", as Maria's sympathies lay firmly with the Union cause.[10]

Civil War

Even though Maryland did not secede from the Union, Steuart's loyalty lay with the South, as did that of his father. He commanded one of the Baltimore city militias during the riot of April 1861, following which Federal troops occupied Baltimore, an incident which was arguably the first armed confrontation of the Civil War.

Steuart resigned his captain's commission on April 16, 1861[11] and soon entered the service of the Confederate army as a cavalry captain. He and his father were determined to do their utmost to prevent Union soldiers from occupying Maryland. On April 22 Steuart wrote to Charles Howard, President of the Board of Baltimore Police:

- "If the Massachusetts troops are on the march [to Annapolis] I shall be in motion very early tomorrow morning to pay my respects to them".[12]

However, events did not move in their favor and, in a letter to his father, Steuart wrote:

- "I found nothing but disgust in my observations along the route and in the place I came to – a large majority of the population are insane on the one idea of loyalty to the Union and the legislature is so diminished and unreliable that I rejoiced to hear that they intended to adjourn...it seems that we are doomed to be trodden on by these troops who have taken military possession of our State, and seem determined to commit all the outrages of an invading army." [13]

Steuart's efforts to persuade Maryland to secede from the Union were in vain. On April 29, the Maryland Legislature voted 53–13 against secession. and the state was swiftly occupied by Union soldiers to prevent any reconsideration. Steuart's decision to resign his commission and join the rebels would soon cost his family dear. The Steuart mansion at Maryland Square was confiscated by the Union Army and Jarvis Hospital was erected on the estate, to care for Federal wounded.[9] However, Steuart was welcomed by the Confederacy as "one of Maryland's most gifted sons", and it was hoped by Southerners that other Marylanders would follow his example.[14]

First Bull Run

Steuart soon became lieutenant colonel of the newly formed 1st Maryland Infantry, serving under Colonel Arnold Elzey,[15] and fought with distinction at the First Battle of Bull Run, taking part in the charge that routed the Union army. Very soon after he was promoted to colonel, and assumed command of the regiment,[14] succeeding Elzey,[15] who was promoted to brigadier general. He soon began to acquire a reputation as a strict disciplinarian and gained the admiration of his men,[16] though he was initially unpopular as a result. Steuart was said to have ordered his men to sweep the bare dirt inside their bivouacs and, rather more eccentrically, was prone to sneaking through the lines past unwitting sentries, in order to test their vigilance.[14] On one occasion this plan backfired, as Steuart was pummeled and beaten by a sentry who later claimed not to have recognized the general.[17] Eventually however, Steuart's "rigid system of discipline quietly and quickly conduced to the health and morale of this splendid command."[5] According to Major W W Goldsborough, who served in Steuart's Maryland Infantry at Gettysburg: "...it was not only his love for a clean camp, but a desire to promote the health and comfort of his men that made him unyielding in the enforcement of sanitary rules. You might influence him in some things, but never in this".[18] George Wilson Booth, a young officer in Steuart's command at Harper's Ferry in 1861, recalled in his memoirs: "The Regiment, under his master hand, soon gave evidence of the soldierly qualities which made it the pride of the army and placed the fame of Maryland in the very foreground of the Southern States".[19] Other historians have been less kind, seeing Steuart as a "tough and nasty martinet" and as a "cruel disciplinarian",[20] suggesting that such "old army" discipline was not the best way to mould and lead what was essentially a citizen army.[20]

Shenandoah Campaign and the First Battle of Winchester

Steuart was promoted to brigadier general on March 6, 1862,[15] commanding a brigade in Major General Richard S. Ewell's division during Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley campaign. On May 24 Jackson gave Steuart command of two cavalry regiments, the 2nd and 6th Virginia Cavalry regiments.[14] At the First Battle of Winchester, on May 25, 1862, Jackson's army was victorious, and the defeated Federal infantry retreated in confusion. The conditions were now perfect for the cavalry to complete the victory,[21] but no cavalry units could be found to press home the advantage. Jackson complained: "never was there such a chance for cavalry! Oh that my cavalry were in place!" [22] The exhausted infantry were forced forward again, while Lieutenant Sandie Pendleton of Jackson's staff was sent to find Steuart.[22]

Pendleton eventually found Steuart and gave him the order to pursue Banks' retreating army but the general delayed, wasting valuable time on a point of military etiquette. He declined to obey the order until it came through General Ewell, his immediate divisional commander.[14][23] The proper channels had not been followed. A frustrated Pendleton then rode two miles to find Ewell, who duly gave the order, but "seemed surprised that General Steuart had not gone on immediately".[22]

Steuart eventually gave chase and overtook the advance of the Confederate infantry, picking up many prisoners, but, as a result of the delay, the Confederate cavalry did not overtake the Federal army until it was, in the words of Jackson's report, "beyond the reach of successful pursuit". Jackson continued: "There is good reason for believing that had the cavalry played its part in this pursuit, but a small portion of Banks' army would have made its escape to the Potomac".[24]

It remains unclear precisely why Steuart was reluctant to pursue Banks' defeated army more vigorously, and contemporary records shed little light on the matter.[25] It may be that his thirteen years' training as a cavalry officer led him to obey orders to the letter, with little or no room for personal initiative or variation from strict due process.[25] No charges were brought against him however, despite Jackson's reputation as a stern disciplinarian.[26] It is possible that Jackson's leniency had to do with the strong desire of the Confederacy to recruit Marylanders to the Southern cause, and the need to avoid offending Marylanders who might be tempted to join Lee's army.[26]

Soon after Winchester, on June 2, Steuart was involved in an unfortunate incident in which the 2nd Virginia Cavalry was mistakenly fired on by the 27th Virginia Infantry.[27] Colonels Thomas Flournoy and Thomas T. Munford went to General Ewell and requested that their regiments, the 6th and 2nd Virginia Cavalry, be transferred to the command of Turner Ashby, recently promoted to Brigadier General. Ewell agreed, and went to Jackson for final approval.[27] Jackson gave his consent, and for the remainder of the war Steuart would serve as an infantry commander.

Battle of Cross Keys

At the Battle of Cross Keys (June 8, 1862), Steuart commanded the 1st Maryland Infantry, which was attacked by, and successfully fought off, a much larger Federal force. However, Steuart was severely injured in the shoulder by grape shot, and had to be carried from the battlefield.[28] A ball from a canister shot had struck him in the shoulder and broken his collarbone, causing a "ghastly wound".[28] The injury did not heal well, and did not begin to improve at all until the ball was removed under surgery in August. It would prevent him from returning to the field for almost an entire year, until May 1863.[14]

Gettysburg Campaign and the advance into Maryland

Upon his recuperation and return to the army, Steuart was assigned by Gen. Robert E. Lee to command the Third Brigade, a force of around 2,200 men,[30] in Major General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division, in the Army of Northern Virginia. The brigade's former commander, Brigadier General Raleigh Colston, had been relieved of his command by Lee, who was disappointed by his performance at the Battle of Chancellorsville.[14] The brigade consisted of the following regiments: the 2nd Maryland (successor to the disbanded 1st Maryland), the 1st and 3rd North Carolina, and the 10th, 23rd, and 37th Virginia. Rivalries between the various state regiments had been a recurring problem in the brigade and Lee hoped that Steuart, as an "old army" hand, would be able to knit them together effectively. In addition, by this stage in the war Lee was desperately short of experienced senior commanders.[31] However, Steuart had only been in command for a month when the Gettysburg Campaign got under way.[14]

In June 1863 Lee's army advanced north into Maryland, taking the war into Union territory for the second time. Steuart is said to have jumped down from his horse, kissed his native soil and stood on his head in jubilation. According to one of his aides: "We loved Maryland, we felt that she was in bondage against her will, and we burned with desire to have a part in liberating her".[14] Quartermaster John Howard recalled that Steuart performed "seventeen double somersaults" all the while whistling Maryland, My Maryland.[32] Such celebrations would prove short lived, as Steuart's brigade was soon to be severely damaged at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863). At first however, Lee's advance north went well. At the Second Battle of Winchester (June 13–15, 1863) Steuart fought with Johnson's division, helping to bring about a Confederate victory, during which his brigade took around 1,000 prisoners and suffered comparatively small losses of 9 killed, 34 wounded.[33]

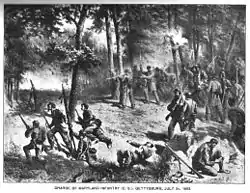

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863) was to prove a turning point in the war, and the end of Lee's advance. Steuart's men arrived at Gettysburg "exhausted and footsore...a little before dusk" on the evening of July 1, following a 130-mile (210 km) march from Sharpsburg, "many of them barefooted".[30] Steuart's men attacked the Union line on the night of July 2, gaining ground between the lower Culp's Hill and the stone wall near Spangler's Spring. But fresh Federal reinforcements blocked his further advance, and no further ground was gained. During the night a large number quantity of Union artillery was wheeled into place, the sound of which caused the optimistic Steuart to hope that the enemy was retreating in its wagons.[14]

The morning of July 3 revealed the full scale of the Union defenses, as enemy artillery opened fire at a distance of 500 yards with a "terrific and galling fire", followed by a ferocious assault on Steuart's position.[30] The result was a "terrible slaughter" of the Third Brigade, which fought for many hours without relief, exhausting their ammunition, but successfully holding their position.[30] Then, late on the morning of July 3, Johnson ordered a bayonet charge against the well-fortified enemy lines, "confident of their ability to sweep him away and take the whole Union line in reverse".[34] Steuart was appalled, and was strongly critical of the attack, but direct orders could not be disobeyed,[35] and Steuart gave the order to "Left face" and "file right", sending his men into heavy enfilading fire.[34] Steuart's Third Brigade advanced against the Union breastworks and attempted several times to wrest control of Culp's Hill, a vital part of the Union Army defensive line. The result was a "slaughterpen",[30] as the Second Maryland and the Third North Carolina regiments courageously charged a well-defended position strongly held by three brigades, a few reaching within twenty paces of the enemy lines.[30] So severe were the casualties among his men that Steuart is said to have broken down and wept, wringing his hands and crying "my poor boys".[29] Overall, the failed attack on Culp's Hill cost Johnson's division almost 2,000 men, of which 700 were accounted for by Steuart's brigade alone—far more than any other brigade in the division. At Hagerstown, on the 8th July, out of a pre-battle strength of 2,200, just 1,200 men reported for duty.[30] The casualty rate among the Second Maryland and Third North Carolina was between one half and two-thirds, in the space of just ten hours.[30]

Even though Steuart had fought bravely under extremely difficult conditions, neither he nor any other officer was cited by Johnson in his report.[36] Gettysburg marked the high-water mark of the Confederacy; thereafter Lee's army would retreat until its final surrender to General Grant at Appomattox Court House.

Battle of Payne's Farm

During the winter of 1863 Steuart's Marylanders again saw action, at the Battle of Mine Run, also known as the battle of Payne's Farm. On November 27 Steuart's brigade was among the first to be attacked by Union soldiers, and Johnson himself rode to Steuart's aid, bringing reinforcements.[37] Steuart, bringing up the Confederate rear, halted his brigade and swiftly formed a line of battle in the road, to repel the Union attack. Confused fighting followed during which the Confederates fell back taking heavy losses, but prevented a Union breakthrough. Steuart himself was wounded for the second time, sustaining an injury to his arm.[37] According to a historical marker which commemorates the engagement, Steuart's "boldness against a vastly superior force...helped to stall the advance of the entire Union army".[38]

Battle of the Wilderness

In the summer of 1864, Steuart saw severe action during the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5–7, 1864). Steuart led his North Carolina infantry against two New York regiments, causing Union losses of almost 600 men.[5] During the battle his brother, Lieutenant William James Steuart, was severely wounded in the hip, and was sent to Guinea station, a hospital for officers in Richmond, Virginia. There, on 21 May 1864, he died of his injuries.[39] A friend of the family at the University of Virginia wrote to their bereaved father:

- "You will not charge me, I trust, with intruding on the sacredness of your grief, if I cannot help giving expression to my deep, heartfelt sympathy with your great sorrow. You have sacrificed so much for the righteous cause already, that I know you will present this last and most precious offering also with the fortitude of your character and the submission of a Christian. Still, I know how valuable this son of yours had been to your interests, how dear to your heart, and I cannot tell you, with what deep and sincere grief I heard of your terrible loss." [40]

Disaster at Spotsylvania

Soon afterward, at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 8–21, 1864), Steuart was himself captured, along with much of his brigade, during the brutal fighting for the "Mule Shoe" salient. The Mule Shoe salient formed a bulge in the Confederate lines, a strategic portion of vital high ground but one which was vulnerable to attack on three sides. During the night of May 11, Confederate commanders withdrew most of the artillery pieces from the salient, convinced that Grant's next attack would fall elsewhere.[41] Steuart, to his credit, was alert to enemy preparations and sent a message to Johnson advising him of an imminent enemy attack and requesting the return of the artillery.[42]

Unfortunately, shortly before dawn on May 12, Union forces comprising three full divisions (Major General Winfield S. Hancock's II Corps) attacked the Mule Shoe through heavy fog, taking the Confederate forces by surprise. Exhaustion, inadequate food, lack of artillery support, and wet powder from the night's rain contributed to the collapse of the Confederate position as the Union forces swarmed out of the mist, overwhelming Steuart's men and effectively putting an end to the Virginia Brigade.[43] Confederate muskets would not fire due to damp powder, and apart from two remaining artillery pieces, the Southerners were effectively without firearms.[41] During the thick of the fierce hand-to-hand fighting that followed, Steuart was forced to surrender to Colonel James A. Beaver of the 148th Pennsylvania Infantry. Beaver asked Steuart "Where is your sword, sir?", to which the general replied, with considerable sarcasm, "Well, suh, you all waked us up so early this mawnin' that I didn't have time to get it on."[44] Steuart was brought to General Hancock, who had seen Steuart's wife Maria in Washington before the battle and wished to give her news of her husband. He extended his hand, asking "how are you, Steuart?"[45] But Steuart refused to shake Hancock's hand; although the two men had been friends before the war, they were now enemies. Steuart said: "Considering the circumstance, General, I refuse to take your hand", to which Hancock is said to have replied, "And under any other circumstance, General, I would have refused to offer it."[46] After this episode, an offended Hancock then left Steuart to march to the Union rear with the other prisoners.[47]

After the battle, Steuart was sent as a prisoner of war to Charleston, South Carolina, and was later imprisoned at Hilton Head, where he and other officers were placed under the fire of Confederate artillery.[48] The fighting at Spotsylvania was to prove the end of his brigade. Johnson's division, 6,800 strong at the start of the battle, was now so severely reduced in size that barely one brigade could be formed. On May 14 the brigades of Walker, Jones, and Steuart were consolidated into one small brigade under the command of Colonel Terry of the 4th Virginia Infantry.[49]

Petersburg, Appomattox and the end of the war

Steuart was exchanged later in the summer of 1864, returning to command a brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, in the division of Major General George Pickett.[48] Steuart's brigade consisted of the 9th, 14th, 38th, 53rd and 57th Virginia regiments, and served in the trenches north of the James River during the Siege of Petersburg (June 9, 1864 – March 25, 1865).[48] By this stage of the war, Confederate supplies had dwindled to the point where Lee's army began to go hungry, and the theft of food became a serious problem. Steuart was forced to send armed guards to the supply depot at Petersburg in order to ensure that his men's packages were not stolen by looters.[50]

He continued to lead his brigade in Pickett's division during the Appomattox Campaign (March 29 – April 9, 1865), at the Battle of Five Forks (April 1, 1865), and at Sayler's Creek (April 6, 1865), the last two battles marking the effective end of Confederate resistance. During Five Forks General Pickett had been distracted by a shad bake, and Steuart was left in command of the infantry, as it bore the brunt of a huge Union assault, with General Sheridan leading around 30,000 men against Pickett's 10,000.[51] The consequences were even more disastrous than at Spotsylvania the previous year, with at least 5,000 men falling prisoner to Sheridan's forces.[51] The end of Confederate resistance was now just days away. At Sayler's Creek Lee's starving and exhausted army finally fell apart. Upon seeing the survivors streaming along the road, Lee exclaimed in front of Maj. Gen. William Mahone, "My God, has the army dissolved?" to which he replied, "No, General, here are troops ready to do their duty."[52]

Steuart continued fighting until the end, finally surrendering with Lee to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, one of 22 brigadiers out of Lee's original 146.[53] According to one Maryland veteran, "no-one in the war gave more completely and conscientiously every faculty, every energy that was in him to the Southern cause".[54]

After the war

After the war's end, Steuart returned to Maryland, and swore an oath of loyalty to the Union.[55] He farmed at Mount Steuart, a two-storey farmhouse on a hillside near the South River, south of Edgewater. The house no longer exists, having since been destroyed by fire.[56] He also served as commander of the Maryland division of the United Confederate Veterans.

Maryland Square, the house owned by Steuart and his father before the war, was returned to the family in 1866 but Steuart chose not to live there, taking rooms instead at the Carrollton Hotel in Baltimore.[56]

The end of war saw Steuart reunited with his family, but domestic happiness did not follow. In the early 1890s he took in a housekeeper by the name of Fanny Grenor, causing a "still further estrangement between husband and wife... [which also] resulted in much bitter feeling on the part of the two children, Mrs Leibeg and Mrs Davis, these ladies holding with the mother that General Steuart should have selected some other housekeeper".[10]

Steuart died on 22 November 1903 at the age of 75 at South River, Maryland, of an ulcer.[36] He died intestate, leaving an estate valued at around $100,000, which was soon contested by Miss Grenor, who sought "pay for the 10 years she had acted as housekeeper, and also performed other duties of a more or less menial character".[10]

Steuart is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore with his wife Maria, who died three years later, in 1906. They were survived by their two daughters, Marie and Ann.[9] Perhaps not surprisingly, as Maryland had remained in the Union throughout the war, there is no monument to Steuart in his home state. However, the Steuart Hill area of Baltimore recalls his family's long association with the city.[57]

Notes

- Nelker, p.150

- White, Roger B,"Steuart, Only Anne Arundel Rebel General", The Maryland Gazette, 13 November 1969

- Nelker, p.131, Memoirs of Richard Sprigg Steuart.

- Cullum, p.225

- Article on Steuart at www.stonewall.hut.ru Archived 2009-10-31 at the Wayback Machine Accessed January 8, 2010

- Miller, p.49

- Wikitree Retrieved 23 January 2018

- Nelker, p67

- Nelker, p.120.

- Baltimore Sun, General Steuart's Estate, December 19, 1903

- Cullum, George Washington, p.226, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Retrieved Jan 16 2010

- Lockwood & Lockwood, p.210, The Siege of Washington: The Untold Story of the Twelve Days That Shook the Nation Retrieved June 2012

- Mitchell, Charles W., p.102, Maryland Voices of the Civil War. Retrieved February 26, 2010

- Tagg, p.273.

- Warner p.290

- Goldsborough, p.30.

- Green, p.125.

- Goldsborough, p.119

- Booth, George Wilson, p.12, A Maryland Boy in Lee's Army: Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States, Bison Books (2000). Retrieved Jan 16 2010

- Patterson, p.17

- Freeman, p.192

- Freeman, p.193

- Allan, p.143.

- Goldsborough, p.46.

- Freeman, p.215

- Freeman, p.216

- Freeman, p.199

- Goldsborough, p.56.

- Goldsborough, p.109.

- Steuart's brigade at Gettysburg, by his aide-de-camp, Reverend Randolph H. McKim Accessed January 8, 2010

- Freeman, p.529

- Goldsborough, p.98.

- Steuart's reports from the Gettysburg Campaign, June 19, 1863 Accessed January 8, 2010

- Blair, p.48

- Goldsborough, p.106.

- Tagg, p.275.

- Freeman, p.636

- www.hmdb.org Retrieved May 2012

- Nelker, p.67

- Mitchell, p.339

- Robertson, p.223.

- Freeman, p.680

- Dowdey, p.204.

- Robertson, p.225.

- Jordan, p.130

- Hoptak, John David (August 12, 2009), Happy 181st Birthday. . ., The 48th Pennsylvania Infantry/Civil War Musings, Accessed January 7, 2009

- Porter, p.105

- Davis, p.3

- Robertson, p.226.

- Hess, p.220 Accessed January 8, 2010

- Freeman, p.780

- Freeman, vol. 3., p. 711.

- Freeman, p,811

- Pfantz, p.313

- Sjoberg, Leif, p.72, American Swedish (1973) Retrieved March 1, 2010

- White, Roger B, Article in The Maryland Gazette, "Steuart, Only Anne Arundel Rebel General", November 13, 1969

- Steuart, William Calvert, Article in Sunday Sun Magazine, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past", Baltimore, February 10, 1963

References

- Allan, Col. William. Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and the Army of Northern Virginia, 1862. New York: Da Capo Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-306-80656-8. First Work, History of the Campaign of Gen. T. J. (Stonewall) Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, First Published Boston: Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1880. Second Work, The Army of Northern Virginia in 1862, First Published Boston, Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1882.

- Baltimore Sun, General Steuart's Estate, December 19, 1903

- Blair, Jayne E., Tragedy at Montpelier - the Untold Story of Ten Confederate Deserters from North Carolina, Heritage Books (2006) ISBN 0-7884-2370-3

- Cullum, George Washington, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U. S. Military, J. Miller (1879), ASIN: B00085668C

- Davis, William C, Editor, The Confederate General, Volume 6, National Historical Society, ISBN 0-918678-68-4.

- Dowdey, Clifford, Lee's Last Campaign, University of Nebraska Press (1993), ISBN 0-8032-6595-6.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1946. ISBN 978-0-684-85979-8.

- Goldsborough, W. W., The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1.

- Green, Ralph, Sidelights and Lighter Sides of the War Between the States, Burd St Press (2007), ISBN 1-57249-394-1.

- Hess, Earl J. In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8078-3282-0.

- Jordan, David M. Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier's Life. Bloomfield: Indiana University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-253-36580-4.

- Maryland Gazette, Steuart: Only Anne Arundel Rebel General, Thursday November 13, 1969, by Roger A. White

- Miller, Edward A, Lincoln's Abolitionist General: The Biography of David Hunter, University of South Carolina Press (1997). ISBN 978-1-57003-110-6

- Nelker, Gladys P., The Clan Steuart, Genealogical Publishing (1970).

- Patterson, Gerard A., Rebels from West Point - the 306 US Military Academy Graduates who Fought for the Confederacy, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA (2002). ISBN 0-8117-2063-2

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-8078-2118-3.

- Porter, Horace. Campaigning With Grant. New York: The Century Co., 1897. Time-Life Books reprint 1981. ISBN 978-0-8094-4202-7.

- Robertson, James I., Jr. The Stonewall Brigade. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963. ISBN 978-0-8071-0396-8.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Steuart, James, Papers, Maryland Historical Society, unpublished.

- Steuart, William Calvert, Article in Sunday Sun Magazine, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past", Baltimore, February 10, 1963.

- Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg, Savas Publishing (1998), ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- White, Roger B, Article in The Maryland Gazette, "Steuart, Only Anne Arundel Rebel General", November 13, 1969.

External links

- Excerpt from Cullum, George Washington, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U. S. Military, J. Miller (1879) Retrieved on Jan 10 2010

- George H Steuart biography at stonewall.hut.ru Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- Steuart's reports from the Gettysburg Campaign, June 19 1863 Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- George H. Steuart at www.researchonline.net Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- Steuart's capture at Spotsylvania, at 48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- Capture at spotsylvania described in Campaigning with Grant, by Horace Porter Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- Capture at spotsylvania described in William Scott Hancock, by David M. Jordan Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- Detailed account of Steuart's brigade in action at Gettysburg, by his aide-de-camp, Rev. Randolph H. McKim Retrieved on Jan 8 2010

- Gettysburg, Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill by Harry W. Pfanz, p.311 Retrieved on Jan 11 2010

- Lincoln's Abolitionist General: The Biography of David Hunter, by Edward A. Miller, University of South Carolina Press (1997) Retrieved on Jan 12 2010

- Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders, by Ezra Warner Retrieved Jan 12 2010

- A Maryland Boy in Lee's Army: Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States, by George Wilson Booth, Bison Books (2000). Retrieved Jan16 2010

- George H. Steuart at www.2ndmdinfantryus.org/csinf1.html Retrieved February 20, 2010