Firefighting in the United States

Firefighting in the United States dates back to the earliest European Colonies in the Americas. Early firefighters were simply community members who would respond to neighborhood fires with a bucket. The first dedicated volunteer fire brigade was established in 1736 in Philadelphia. These volunteer companies were often paid by insurance companies in return for protecting their clients.

.jpg.webp)

As cities grew this method became unreliable, and the first professional fire department was established in Cincinnati in 1853. By the 20th century fire departments were forced to adapt to more modern hazards and dangers, such as high rise and hazardous material fires. They also began to expand their services to include other, non-fire, public safety needs including vehicle rescue and EMS service.[1] As of 2018, 62% of fire departments offered some form of emergency medical response.[2]

Firefighters in the United States today are organized along paramilitary lines, and are most often grouped into city or county departments. They utilize modern equipment. Professional fire departments protect 68% of the US population, with a total of 1,216,600 firefighters serving in 27,228 fire departments nationwide and responding to emergencies from 58,150 fire stations.[2][3] Union firefighters are represented by the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF). The New York City Fire Department is the largest in the United States.

Firefighters in America are widely respected, with over 80% of Americans considering firefighting to be a prestigious occupation in 2018.[4]

Overview

A Fire department responds to a fire every 23 seconds throughout the United States.[5] Fire departments responded to 33,602,500 calls for service in 2015. 21,500,000 were for medical help, 2,533,500 were false alarms, and 1,345,500 were for actual fires.[6]

Since at least 1980, calls for fires have decreased as a proportion of total calls and in absolute numbers from 3,000,000 to 1,400,000 in 2011, while in the same period medical calls have increased from 5,000,000 to 19,800,000.[7][8] While some medical calls are dealt with only by ambulances, it is common for fire engines to respond to them as well.[9]

The professionalization of American firefighting was largely a result of three factors: the steam fire engines, the fire insurance companies, that demanded the municipalization of firefighting, and the theory that suggested payment of wages would naturally result in improved service.[10] Paid firefighters may be union or non-union. Union American firefighters are represented and united in the International Association of Fire Fighters with headquarters in Washington, D.C. However, many municipalities still rely on volunteer, paid on call, or part-time firefighters. These non full-time firefighters are rarely union, and their interests are represented by the National Volunteer Fire Council.

The United States Fire Administration provides national leadership to local fire services. The fire departments report fires and other incidents according to the National Fire Incident Reporting System, which maintains records of the incidents in a uniform manner. The National Fire Protection Association sets and maintains minimum standards and requirements for firefighting duties and equipment. The suppression of wildfires is regulated by the United States Department of Agriculture, US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This is done through the National Wildland Coordination Center.

The two million fire calls that American fire departments respond to each year represent the highest figures in the industrialized world. Each year thousands of people die, tens of thousands of people are injured, and property damage reaches billions of dollars. Indirect costs, such as temporary lodging expenses, lost time at work, medical expenses, and psychological damages are equally alarming (The United States Fire Administration 1996). According to American Red Cross statistics, the annual losses from floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, and other natural disasters combined in the United States average just a fraction of those from fires. House fires in particular are one of the most common tragedies facing emergency disaster workers in recent history. According to the US Fire Administration, the United States has a more severe fire problem than generally perceived. In inner city Pennsylvania neighborhoods, house fires have greatly increased, especially in socially and economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. An alarming trend in these specific house fires is that sixty percent of these houses do not have working smoke detectors. Additionally, these households are prone to using supplemental heating devices and substandard extension cords that are not Underwriters Laboratories (UL) compliant. UL compliant extension cords are labeled with valuable information as to the use, size, and rating of the cord (Dunston, 2008, p. 2).

History

Firefighting in the United States can be traced back to the 17th century when, after a great conflagration in Boston in 1631, the Massachusetts Bay Colony passed a law banning smoking in public places.[11]

New Amsterdam established the colonies' first firefighting system in 1647.[12] Fire wardens inspected the houses and chimneys, fining for potential hazard. An eight-man team called a rattle watch patrolled the streets at night. When a fire was detected, they shook wooden rattles to alert townspeople. In 1711 the concerned Americans formed the so-called mutual fire societies of approximately twenty members each. When fire struck a society member, other members rushed for assistance. The first water-pumping engines were imported to New York in the 1730s.

Fire companies

Benjamin Franklin founded the first American volunteer fire company in Philadelphia in 1736. Such companies were soon organized in other colonies. Among those who served as volunteer firefighters were George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Hancock, Samuel Adams and Paul Revere.[13] In 1818 the first known female firefighter Molly Williams rose to prominence in New York, when she took her place with the men on the drag ropes and pulled the pumper to the fire through the deep snow. Volunteer firefighters were honored with frequent stanzas in urban newspapers and made the subject of heroizing prints by the popular American printmaking firm Currier & Ives. Nathaniel Currier, of Currier & Ives, served as a volunteer firefighter in New York City during the 1850s.

In the early days of the fire service, fire companies were, more or less, social organizations. And, being an accepted member meant a certain social status in the community. Remnants of that social status can still be found today in the traditional style firefighter's parade helmets that resemble top hats worn by the early firefighters. Money that was used to help fund the organization was obtained by insurance company payouts from fighting fires. Firefighters could easily tell just which homeowners had fire insurance and who didn't by fire insurance marks located on the front of the home. Often it was a problem for homeowners who did not have insurance to have the fire company respond to a fire in their home and effectively remove belongings and such because the firefighters knew that there wouldn't be any money in it for them.

The first fire companies in Washington D.C. – the Union Fire Company, the Columbia Fire Company and the Anacostia Fire Company – were organized in 1804 to serve the White House, the Capitol and the neighborhood of Anacostia, respectively. By the 1840s and 1850s the differences between companies within the same city had become quite significant.

With few exceptions like in Savannah, Georgia, firefighters denied African Americans the opportunity to join the companies or form their own ones. As early as 1818 in Philadelphia the local free black community attempted to form the African Fire Association. Meanwhile, some southern cities like Charleston and Savannah relied on African American labor.

Fire apparatus

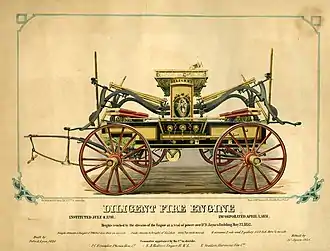

American firefighters built, designed or assigned specifications for their equipment. Particularly, they dedicated themselves to the engines and viewed them as integral to the fire company identity.[14]

Blacksmith Patrick Lyon of Philadelphia was an innovator in building firefighting apparatus. In 1800, he patented a hand-pumped engine that was the most powerful in the United States,[15] and he built the first hose wagon in 1804, which eliminated the need for bucket brigades in cities.[16] Lyon's masterpiece was the hand-pumper Diligent, which, at 32-years-old, outperformed the new Cincinnati-built steam pumper Young America in a famous 1852 contest.[17]

In 1853 the first practical, steam powered, fire engine was tested in Cincinnati (OH).[18] It was created by Abel Shawk, Alexander Bonner Latta, and Miles Greenwood. The engine was then named Uncle Joe Ross after a city council member.[19]

Fire departments

Before the 1850s, there were only volunteer fire companies. In 1853 Cincinnati, Ohio, became the first city with a fully paid fire department, followed four years later by the St. Louis Fire Department in St. Louis, Missouri. In 1855 the Metropolitan Hook and Ladder Company Number 1 Firehouse, Washington's oldest extant firehouse, was built at Massachusetts Avenue. Then in 1859 came the fully paid Fire Force in Indianapolis (IFD) by the guidance and authority of Mayor Samuel Dunn Maxwell going as far as to ban the volunteer departments from the city. As a proud Norse Celt he vowed that “Indianapolis will only accept aggressive paid firemen possessing the bravery and strength of a Highland Warrior and the dedication to battle like the Viking”. Many volunteer companies disbanded around America’s larger cities, however Volunteer fire departments still protect property and play an important role, as they do even today. Later the specialized life-saving units in American fire departments - the pompier corps - were formed.

In the 20th century, the nature of an American firefighter's job began to change. Structural firefighting was still the main purpose of the department, but more specialized training and education, such as for high-rise structure fires, confined space environments and building construction education were included and emphasized. Other disciplines were taken on as responsibilities in lifesaving. An example of such is the practice of Paramedicine which debuted in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Presently, almost all fire departments across the United States have been trained in and perform technical rescue, vehicle rescue, high-angle rescue, wildland firefighting and hazardous materials incidents. Additionally, almost all career departments as well as many volunteer departments have emergency medical assets at their immediate disposal.

Several notable events have killed many firefighters. Japanese planes attacked Honolulu Fire Department (HFD) personnel responding to the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, killing three. 343 New York City Fire Department (FDNY) firefighters were killed when the World Trade Center collapsed during the attacks of September 11, 2001. In 2007, the Sofa Super Store fire in Charleston, South Carolina, killed nine members of the City of Charleston Fire Department.

In 2011, there were about 1.1 million firefighters in the country. 31% were paid, the remainder volunteer. The nation has seen an increase in paid positions; 8.6% decrease in volunteers from 2008 to 2011.[20] As of 2018, this decline continued, with 33% or 370,000 being career firefighters and 67% or 745,000 being volunteers.[2]

Company types

Fire companies come in several types. Note that the names below are not standard and have numerous local variations.

Engine Company or Pumper Company

- A unit that pumps water. Modern engines are almost always "triple-combination" units that have a pump, a tank of water, and hoses. This company has the primary responsibility of supplying water to a scene, to locate and confine the fire, and extinguish the fire. some engines or pumpers are equipped for some levels of medical first response or medium rescue response.

Truck Company or Ladder Company

- A unit that carries ladders and an aerial device and other equipment to access buildings above ground level and assist in other emergencies. Some Truck Companies or Ladder Companies have been designated Quint Trucks. Primarily, the Truck Company or Ladder Company performs the ladder work and supplies master streams to the fireground. The Truck Company or Ladder Company also performs structural ventilation and overhaul, primary and secondary search & rescue, securing of utilities, and often supplies rapid intervention teams. Some ladder trucks also have rescue and medical equipment. There are several types of Ladder Companies or Truck Companies in the United States fire service. this includes Aerial Tower companies, Hook & Ladder companies (also known as Tractor Drawn Aerial Ladder Trucks or Tiller Aerial Ladder Trucks), Tower Ladder companies, etc. Some Aerial Ladder Trucks will also act as Quint trucks if necessary.

Heavy Rescue Company

- A unit that carries a large variety of tools and equipment to assist in the search and rescue of victims at an incident such as a fire, traffic collision or other situations. It may or may not provide emergency medical response and may or may not transport patients to hospital depending on its response profile. The New York City Fire Department has five heavy rescue companies. The Chicago Fire Department has four heavy squads in service. some departments, including the Albany (New York) Fire Department and Baltimore City Fire Department have only one heavy rescue company.

Squad Company

- This type of unit has many different local and regional definitions. In the New York City Fire Department and Baltimore City Fire Department, for example, a Squad Company is a hybrid company consisting of an apparatus equipped with supplies necessary to perform some levels of rescue operations as well as engine company and truck company operations. In some areas it is identical to a Rescue Unit or a Medic company. A Squad in the Los Angeles County Fire Department is a small truck which is the primary response vehicle for rescue and medical responses. it carries a small amount of firefighting, rescue and medical equipment. A fictional Squad example is Squad 51 from the TV Show Emergency!. it was used by two paramedics in the Los Angeles County Fire Department to respond to a variety of emergencies from medical calls to fire incidents and others

Medic Unit/Rescue Ambulance

- A unit that provides EMS, often at the advanced life support (paramedic) or basic life support/EMT (Emergency Medical Technician) response level. Many fire services offer some form of medical response and ambulance units or medic companies may or may not transport patients to hospitals.

Quint Company

- Short for quintuple-combination engine. The unit has the three items that an engine does -- pump, tank, hose -- but also carries ground ladders and has an aerial device and specialized equipment and tools for certain situations.

Tanker or Tender Truck

- A unit that has a large water tank. It may or may not also have a pump.

Brush Patrol Unit

- A unit usually built on a heavy duty pickup chassis with equipment for fighting brush fires. The Brush unit Typically responds with an engine to major fires, though the brush unit may also respond alone.

Helicopter or air ambulance apparatus

- Depending on the department a helicopter may be in use as an air ambulance or a suppression and Fire observation tool for brush fires. Some are even used for both as in the case of departments like the Los Angeles Fire Department. These units have specialized Emergency Medical Services equipment or firefighting tools to help at certain rescue incidents or fire scenes.

Chief sedan vehicle

- A command car containing a lower ranking chief officer in command of an area/district/division/battalion of a department that contains usually around 3 or more fire stations that responds to large fires, mass casualty incidents, and any emergency with more than one unit responding. These vehicles have equipment that assist in providing command and control at fires or other incidents.

EMS Supervisor or EMS captain sedan

- Similar to a chief sedan vehicle the EMS Supervisor sedan or EMS captain sedan contains a chief officer or other officers for emergency medical services which usually responds to large emergencies, and is usually tasked with directing medical resources on scene. These units have specialized equipment to help these members give instructions and provide command and control at certain scenes.

Specialized Firefighting Categories

Consists of, but not limited to:

- -Structural firefighting

- -Highrise firefighting

- -Confined space firefighting

- -Wildland firefighting

- -Airport firefighting

- -Hazardous Materials firefighting

Organization

U.S. firefighters work under the auspices of fire departments (also commonly called fire protection districts, fire divisions, fire companies, fire bureaus, and fire-rescue companies, etc). These departments are generally organized as local or county government subsidiaries, special-purpose district entities or not-for-profit corporations. They may be funded by the parent government, through millage, fees for services, fundraising or charitable contributions. Some state governments and the federal government operate fire departments to protect their wildlands, e.g., California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE),[21] New Jersey Forest Fire Service,[22] USDA Forest Service – Fire and Aviation Management[23] (see also Smokejumper). Many military installations, major airports and large industrial facilities also operate their own fire departments.

A small number of U.S. fire departments are privatized, that is, operated by for-profit corporations on behalf of public entities. Knox County, Tennessee is among the largest public entities protected by privatized fire departments.[24]

Most larger urban areas have career firefighters. Most rural areas have volunteer or paid on-call firefighters. Smaller towns and suburban areas may have either. 74% of career firefighters are in departments that protect 25,000 or more people. 95% of volunteer firefighters are in departments that protect fewer than 25,000 people and more than half of these are in small, rural departments protecting fewer than 2,500 people. Departments range in size from a handful of firefighters to over 11,400 sworn firefighters and 4,600 additional personnel in the New York City Fire Department. These additional personnel include uniformed emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics. Many U.S. fire departments have emergency medical service corps (EMS), which may be structurally separate from or combined with their firefighting operations, including firefighters cross-trained as EMTs and paramedics.

As of 2014, there were 1,134,400 firefighters in the United States (not including firefighters who work for the state or federal governments or in private fire departments). Of these, 346,150 (31%) are career and 788,250 (69%) are volunteer. These firefighters operate out of 27,198[25] fire departments. Career firefighters represent 15% of all departments but protect approximately two thirds of the U.S. population. Meanwhile, 85% of fire departments are volunteer or mostly volunteer and protect approximately one third of the population.[26] The Firemen's Association of the State of New York (FASNY) provides information, education and training for the volunteer fire and emergency medical services throughout New York State.

Like most U.S. police departments or law enforcement agencies, U.S. fire departments are usually structured in a paramilitary manner. Firefighters are sworn, uniformed members of their departments. Rank-and-file firefighters are equivalent to enlisted personnel; supervisory firefighters are command officers with ranks such as lieutenant, captain, battalion chief, deputy chief and assistant chief, division chief, district chief, etc. Fire departments, especially larger ones, may also be organized into military-style echelons, such as companies, battalions and divisions or districts. Fire departments may also have unsworn or non-uniformed members in non-firefighting capacities such as administration and civilian oversight, e.g., a board of commissioners. While adhering to a paramilitary command structure, most fire departments operate on a much less formal basis than the military.

Firefighting in the United States is becoming more of a profession than it once was. Historically, especially in smaller departments, little formal training of firefighters was required. Now, most states require both career and volunteer firefighters to complete a certificate program at a fire academy. This often includes certifications in Firefighter 1 & 2,[27] as well as Hazardous Materials Awareness & Operations,[28] in accordance with NFPA training standards. Associate's, bachelor's and master's degree programs in firefighting disciplines are available at colleges and universities. Such advanced training is becoming a de facto prerequisite for command in larger departments. The U.S. Fire Administration operates the National Fire Academy, which also provides specialized firefighter training.

Ranks and Insignia

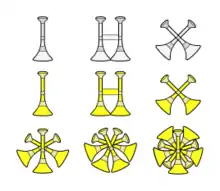

There is no single standard system of rank insignia in use, but certain ranks are common. Many variations in insignia systems make use of the voice trumpet, a type of megaphone, and these are frequently referred to as a "bugle."

- Firefighter (occasionally probie) is the lowest rank. Often, it may be subdivided into grades (such as 1st class, senior, or master firefighter - typically awarded based on seniority), which may or may not be marked on the individual's badge or by uniform rank insignia.

- Driver, engineer, or fire equipment operator are used by many departments. Usually, no insignia is present, but the badge will often note the rank. Some will have multiple grades of this rank.

- Lieutenant is typically used as the lowest "fire officer" rank, usually being marked by a single bugle, often in silver. Some departments instead use a single bar (as in military / police fashion), again, usually in silver. Others may use a single gold bugle or bar. Some departments have multiple grades of lieutenant. An older name for the same rank, still used by some fire departments, is assistant foreman.

- Captain is used in most departments, usually being denoted with a pair of parallel bugles or parallel bars, connected by a thin cross-bar, in either silver or gold. This is frequently used as a senior supervisor of an individual company. A captain will command a single-apparatus firehouse. At a firehouse with two apparatus, there will typically be two captains with one serving as the firehouse's commander. In Philadelphia, for example, a captain of a ladder company is the commanding officer of that firehouse, and the captain of the engine company supervises the medic unit in the station. Although only working on 1 of 4 shifts as the company officer, the captain is the supervising officer of the house overall and is reported to by the lieutenants on the other 3 shifts, even though he/she is not present during those shifts. As with lieutenant, some departments still use the older style, Foreman, instead of captain.

- Senior captain is rarely used, and may be shown as 2 bugles crossed.

- Battalion chief (sometimes division chief or district chief) is often the highest-ranking shift officer that is always on duty at any given time in a smaller department (i.e., the shift commander); or, in larger departments comprising multiple battalions, one would be assigned to supervise a complement of X number of companies in each battalion, district or division. This is common in different parts of the city. (Boston, for example, has 9 district chiefs that operate under 2 division chiefs citywide, supervising a total of 34 engines, 23 ladders, and 2 heavy rescues). This is usually the lowest chief rank. Typical insignia is two crossed gold bugles or two stars, although some departments use 3 bugles or 1 star. Some are occasionally identified with an oak leaf like a US military major, as with the FDNY's BC collar insignia.

- Additional chief grades usually exist between chief and battalion chief; usual insignia is 3 or 4 crossed gold bugles or 3 or 4 stars. Common titles include district chief, division chief, assistant chief, and deputy chief.

- Chief is usually the highest rank of a uniformed member in any given department, traditionally shown with 5 gold bugles or 5 stars.

Additional ranks outside the normal chain may exist; sergeants, majors, and inspectors are other ranks used by some departments. According to the 1986 Anchorage Fire Department Explorer Handbook, Anchorage Fire Department used a single gold bugle for inspectors, and both single silver bugle and single gold bar for lieutenants, depending upon assignment.

Many fire departments use cuff stripes as well as bugles or military style insignia on their dress uniforms. Typically, they are the same in number and color as the bugles / stars worn, but variations exist.

Many departments also frequently display seniority Service stripes (hash marks) on the lower left sleeve of a dress uniform jacket, or sometimes long-sleeved uniform shirts, with years of service varying greatly between individual departments (each stripe typically represents anywhere from 2–5 years of service).

See also

- Firefighting

- Firefighter

- Occupational hazards with fire debris cleanup

References

- "How today's public fire departments were born from private fire brigades". FireRescue1. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Evarts, Ben; Stein, Gary P. (February 2020). "U.S. Fire Department Profile through 2020". National Fire Protection Association Fire Analysis and Research Division. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "National Fire Department Census quick facts". apps.usfa.fema.gov. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- McCarthy, Niall. "America's Most Prestigious Professions In 2016 [Infographic]". Forbes. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "NFPA - Fire statistics". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "NFPA statistics - Fire department calls". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Karter, MJ, Jr. (January 2013). "Fire department calls". NFPA Website. National Fire Protection Association. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Urbina, Ian (September 3, 2009). "Firefighters Become Medics to the Poor". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Sending Firetrucks For Medical Calls : Shots - Health News". NPR. April 11, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Michèle Dagenais, Irene Maver, Pierre-Yves Saunier. Municipal services and employees in the modern city, p. 49

- "Firefighting in the United States: History". US National Fire Academy Handbook. 2007. p. 8. ISBN 9781433056963.

- Maria Mudd-Ruth, Scott Sroka. Firefighting: Behind the Scenes, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998, p. 7

- Ruth, Sroka, p. 8

- Mark Tebeau. Eating smoke, p. 36

- Robert Burns, "When the Watchman Spun his Rattle, Cry Was 'Throw Out Your Buckets!'" Fire Engineering Magazine, vol. 120 (July 1976).

- John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: J. M. Stoddart & Co., third edition, 1879), pp. 417-18.

- Diligent Fire Engine, from Library Company of Philadelphia.

- "NFPA statistics - Key dates in fire history". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Reiner, A. "Liberty Hose Co. No. 2 - Incident Detail". www.lykensfire.com. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Hajishengallis, Olga (September 29, 2013). "Fire departments find it hard to recruit volunteers anymore". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. p. 14A. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- CAL FIRE - Fire Protection

- Department of Environmental Protection

- Fire and Aviation Management

- https://www.ruralmetrofire.com/locations/knox-county-tennessee.html

- "National Fire Department Census quick facts". apps.usfa.fema.gov. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "NFPA report - U.S. fire department profile". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- "NFPA 1001: Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- "NFPA 1072: Standard for Hazardous Materials/Weapons of Mass Destruction Emergency Response Personnel Professional Qualifications". www.nfpa.org. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- AFDE Post 264 Anchorage Fire Department Explorer Handbook, issued 1986.

Further reading

- Dennis Smith. History of Firefighting in America, 1978

- Steven Scher. New York City Firefighting, 1901-2001

- Shawn Royall. Firefighting in Charlotte (North Carolina).

- National Fire Protection Association. U.S. fire department profile through 2003. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association; 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Firefighting in the United States. |

- "Evaluation of Dermal Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Fire Fighters": a report by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- Worker Safety and Health During Fire Cleanup, Division of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH) of California (Cal/OSHA).

- Worker Safety During Fire Cleanup, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.