Exile and death of Pedro II of Brazil

Pedro II of Brazil was the second and last emperor of Brazil. Despite his popularity among Brazilians, Pedro II was removed from his throne in 1889 after a 58-year reign. He was promptly exiled with his family. Despite his deposition, he did not make an attempt to regain power. He died in late 1891 while in Paris, France, after two years in exile.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Early life (1825–40) |

||

| Pedro II | |

|---|---|

Emperor Pedro II around age 61, circa 1887 | |

| Emperor of Brazil | |

| Reign | 7 April 1831 – 15 November 1889 |

| Coronation | 18 July 1841 |

| Predecessor | Pedro I |

| Emperor of Brazil (in exile) | |

| Exile | 15 November 1889 – 5 December 1891 |

| Born | 2 December 1825 Palace of São Cristóvão, Rio de Janeiro |

| Died | 5 December 1891 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Spouse | Teresa of the Two Sicilies |

| Issue | |

| House | House of Braganza |

| Father | Pedro I of Brazil |

| Mother | Maria Leopoldina of Austria |

| Signature | |

Exile

The monarchist reaction after the fall of the empire "was not small, and even less so its repression."[1] The "new regime suppressed with swift brutality and total disdain for civil liberties all attempts to launch a monarchist party or to publish monarchist newspapers."[2] Soon after several popular riots in protest against the coup occurred as well as battles between monarchist Army troops and republican militias.[3] Those were followed by a civil war in which monarchist military and politicians tried to restore the empire in the Federalist Revolution and the Second Navy Rebellion.[4][5] The last monarchist rebellion occurred in 1904, in what was called the Vaccine Revolt.[5][6] They went into exile in Paris, France.

Death

On 23 November 1891, Pedro II appeared at the French Academy of Sciences for the last time to participate in an election.[7][8] The following morning, he dispassionately noted in his diary the news that the dictator Deodoro da Fonseca had resigned: "10:30. Deodoro has quit."[9] He soon afterwards took a long drive in an open carriage along the Seine, even though it was a very cold day. He felt ill after returning to the Hôtel de Bedford that evening.[7][10] The illness progressed into pneumonia during the following days.[7][11] There was no celebration of his birthday on 2 December, with the exception of a simple mass said while he remained in bed. At that time his daughter Isabel, his son-in-law Gaston and his grandchildren were in attendance.[11][12][13] However, he later received several French and Brazilian visitors who had come to offer birthday congratulations.[11]

His health suddenly worsened on the morning of 3 December.[14] Other relatives and friends went to see him once news of the seriousness of the situation began to spread. On 4 December, he received the last sacrament from Abbé Pierre-Jacques-Almeyre Le Rébours, curé of La Madeleine.[15][16] That night Pedro II began declining, and died at 12:35 am on 5 December.[12][13][17] His last words were, "May God grant me these last wishes – peace and prosperity for Brazil..."[14] He was so weakened that he suffered no pain.[16] Pedro II was surrounded by his daughter Isabel, the Count of Eu, his grandchildren (Pedro, Luís, Antonio, Pedro Augusto and Augusto Leopoldo), his sisters Januária and Francisca with their husbands (respectively the Count of Aquila and the Prince of Joinville).[18]

According to the death certificate the causa mortis was acute pneumonia in the left lung.[13][19][20] Pedro II died without abdicating, and Isabel inherited the claim to the throne of the Brazilian Empire.[13] She solemnly kissed her father's hands, and after that, all those present, including dozens of Brazilians already there kissed her hand, recognizing her as the Empress de jure of Brazil.[17][20] The Baron of Rio Branco, who was also present, later wrote: "The Brazilians, thirty and something, went in line and, one by one, sprinkled holy water on the corpse and kissed his hand. I did the same. They were saying farewell to the great dead."[18] Senator Gaspar da Silveira Martins arrived soon after the Emperor's death and, when he saw the body of his old friend, wept convulsively.[21]

Isabel declined an autopsy, which allowed the body to be embalmed at 9 am on 5 December. Six liters of hydrochloride of zinc and aluminum was injected into his common carotid artery.[22] A death mask was also made.[21] Pedro II was attired in the court dress uniform of a Marshal of the Army to represent his position as commander-in-chief of the Brazilian armed forces.[19][22] On his chest were placed the Order of the Southern Cross, the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Order of the Rose. His hands held a silver crucifix sent by Pope Leo XIII. Two Brazilian flags covered his legs.[13][22][23] While the body was being prepared, the Count of Eu found a sealed package in the room, and next to it a message written by the Emperor himself: "It is soil from my country, I wish it to be placed in my coffin in case I die away from my fatherland."[13][24][25] The package, which contained soil from every Brazilian province, was duly placed inside the coffin.[24][26] Three coffins were used: an inner coffin of lead lined with white satin which contained the body, and two outer coffins (one of varnished oak and the other of oak covered by black velvet).[26]

Funeral

In the hours following the death of Pedro II, thousands of people came to the Hôtel de Bedford. Among these were the President of the Council of Ministers, Charles de Freycinet, and the ministers of War and the Navy.[21][23] In a single day, more than 2,000 telegrams were received by the hotel with messages of condolence.[19][26] French president Sadi Carnot was traveling in the south of the country and sent the members of the Military Household to pay homage to the deceased monarch on his behalf.[27] Princess Isabel wished to hold a discrete and private burial ceremony.[28] However, she eventually accepted the French Government's request for a Head of State's funeral. To prevent political disruption,[29] the government decided that the burial would be officially accorded because the Emperor was a recipient of the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur,[19][30] although with the pomp due to a monarch.[13] Requests from Brazil's republican government to deny an official funeral and any public display of the imperial flag were ignored by the French government.[29]

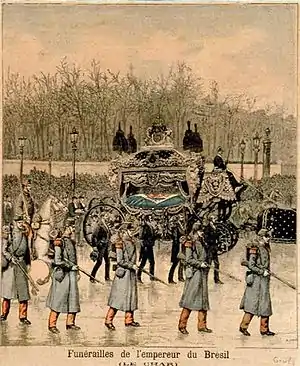

The coffin which contained the body of Pedro II departed the Hôtel de Bedford for La Madeleine on the evening of 8 December.[31] Eight French soldiers bore the coffin, which was covered with the imperial flag.[31][32] A crowd of more than 5,000 people was on hand to witness the cortege.[31] The hearse was the same one used for the funerals of Cardinal Morlot, the duc de Morny and Adolphe Thiers.[19][32]

On the following day, thousands of mourners attended the ceremony at La Madeleine. Aside from Pedro II's family, these included: Amadeo of Savoy, former king of Spain; Francis II, former king of the Two Sicilies; Isabella II, former queen of Spain; Philippe, comte de Paris; and other members of European royalty.[33][34] Also present were General Joseph Brugère, representing President Sadi Carnot; the presidents of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies[19] as well as their members; diplomats; and other representatives of the French government.[35] Nearly all members of the French Academy, the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, the French Academy of Sciences, the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques were in attendance.[19][32] Also among those present were Eça de Queiroz,[19] Alexandre Dumas, fils, Gabriel Auguste Daubrée, Jules Arsène Arnaud Claretie, Marcellin Berthelot, Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau, Edmond Jurien de la Gravière, Julius Oppert, Camille Doucet, and many other notable personages.[32][33] Other governments from the Americans and Europe also sent representatives, as did distant countries such as Ottoman Turkey, China, Japan and Persia.[35] Notably absent was any delegation from Brazil.[19]

.jpg.webp)

Following the services, the coffin was taken in procession to the train station, from whence it would travel to Portugal. Between 200,000[19] and 300,000[36] people lined the route despite incessant rain and cold temperatures.[37] Some 80,000 French military troops marched in the procession.[38] Two carriages carried almost 200 funeral wreaths which bore messages paying homage to the Emperor such as: "To Dom Pedro, Victoria R.I.",[36] "To the great Emperor for whom Caxias, Osório, Andrade Neves and many other heroes fought, Fatherland Volunteers from Rio de Janeiro",[36][39] "A group of Brazilian students in Paris",[36] "Happy times when the thought, the word and the pen were free, when Brazil freed oppressed people…" (sent by the Baron of Ladário, Marquis of Tamandaré, Viscount of Sinimbu, Rodolfo Dantas, Joaquim Nabuco and Taunay),[36] "To the great Brazilian worthy of honors from the Fatherland and Humanity. Ubique Patria Memor."[36] (sent by the Baron of Rio Branco),[25] "From the people of Rio Grande do Sul to the liberal and patriotic king",[36] and "A Brazilian black on behalf of his race".[36] The "state funeral granted by the French republic proclaimed the former’s [Pedro II] personal virtues and popularity and, by implication, distinguished the imperial regime from other monarchies."[40]

All along the route, from France, through Spain and finally into Portugal, people paid homage to Pedro II. But still no representative appeared on behalf of Brazil's republican government.[41] The journey continued on to the Church of São Vicente de Fora near Lisbon, where the body of Pedro II was interred in the Braganza Pantheon on 12 December. His tomb rested between that of his stepmother Amélia and that of his wife Teresa Cristina.[41][42]

Death's repercussions

The Brazilian republican government, "fearful of a backlash resulting from the death of the emperor," banned any official reaction.[43] Nevertheless, the Brazilian people were far from indifferent to Pedro II's demise, and the "repercussions in Brazil were also immense, despite the government's effort to suppress. There were demonstrations of sorrow throughout the country: shuttered business activity, flags displayed at half-staff, black armbands on clothes, death knells, religious ceremonies."[41][44] An article written by João Mendes de Almeida on 7 December 1891 says that, "The news of the death of His Majesty Emperor Dom Pedro II has revealed the feelings of the Brazilian nation towards the Imperial dynasty. The consternation has been general."[45] Solemn "masses were held all over the country, which were followed by eulogies praising Dom Pedro II and the monarchy".[44] So, the "Republic stood by silently, given the strength and impact of reactions."[43]

Police were sent to suppress public demonstrations of sorrow, "provoking serious incidents", although "the people were in sympathy with these manifestants."[46] A popular gathering in memory of the deceased emperor occurred on 9 December and was organized by the Marquis of Tamandaré, Viscount of Ouro Preto, Viscount of Sinimbu, Baron of Ladário, Carlos de Laet, Alfredo d' Escragnolle Taunay, Rodolfo Dantas, Afonso Celso and Joaquim Nabuco.[47] Even old political adversaries of Pedro II praised him, "criticizing his policies" but pointing out "his patriotism, honesty, abnegation, spirit of justice, devotion to work, tolerance and simplicity."[48] Quintino Bocaiúva, one of the main republican leaders, spoke: "The entire world, it may be said, has paid homage which Mr. Dom Pedro de Alcântara has earned through his virtues as a great citizen."[41] Some "members of republican clubs protested against what they characterized as exaggerated sentimentalism in the tributes, seeing in these monarchist maneuvers. They were lonely voices."[41]

Foreign reaction also revealed sympathy towards the monarch. The New York Times on 5 December praised Pedro II, considering him "the most enlightened monarch of the century" and also stating that "he made Brazil as free as a monarchy could be."[49] The Herald wrote: "In another time, and in happier circumstances, he would be worshiped and honored by his subjects and would be known in history as 'Dom Pedro the Good'."[50] The Tribune affirmed that his "reign was serene, peaceable and prosperous."[50] The Times observed, in a long article, "Until November 1889, it was believed that the deceased Emperor and his wife were unanimously beloved in Brazil due to his intellectual and moral qualities and by his affectionate interest for the well-being of his subjects [...] When in Rio de Janeiro he was constantly seen in public; and two times per week he met his subjects, as well as foreign travelers, captivating all with his courtesy."[50]

The Weekly Register wrote, "He looked more like a poet or a scholar than an emperor, but had he had been given the chance to materialize his several projects, without a doubt he would have made Brazil one of the richest countries in the New World."[51] The French periodical Le Jour affirmed that "he was effectively the first sovereign that, following our disaster of 1871, dared to visit us. Our defeat did not move him away from us. France will know how to be grateful."[28] The Globe also wrote that he "was well learned, he was patriotic; he was gentle and indulgent; he had all the private virtues, as well as the public ones, and died in exile."[52]

References

Footnotes

- Salles 1996, p. 194.

- Barman 1999, p. 400.

- Mônaco Janotti 1986, p. 117.

- Martins 2008, p. 116.

- Salles 1996, p. 195.

- Mônaco Janotti 1986, p. 255.

- Carvalho 2007, p. 238.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 26.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 28.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 27.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 29.

- Carvalho 2007, pp. 238–9.

- Schwarcz 1998, p. 489.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 30.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1891.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 601.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1892.

- Lyra 1977, Vol 3, p. 165.

- Carvalho 2007, p. 239.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 602.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 605.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 603.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1893.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1897.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 604.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 606.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 607.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 609.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 613.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1896.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 615.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1899.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1898.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 617.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 618.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1900.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 614.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 620.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 619.

- Barman 1999, p. 401.

- Carvalho 2007, p. 240.

- Calmon 1975, pp. 1900–2.

- Schwarcz 1998, p. 493.

- Mônaco Janotti 1986, p. 50.

- Schwarcz 1998, p. 495.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 610.

- Calmon 1975, p. 1907.

- Carvalho 2007, p. 241.

- Carvalho 2007, pp. 240–1.

- Schwarcz 1998, p. 491.

- Schwarcz 1998, pp. 491–2.

- Schwarcz 1998, p. 492.

Bibliography

- Barman, Roderick J. (1999). Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3510-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Besouchet, Lídia (1993). Pedro II e o Século XIX (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. ISBN 978-85-209-0494-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calmon, Pedro (1975). História de D. Pedro II. 5 v (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carvalho, José Murilo de (2007). D. Pedro II: ser ou não ser (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-359-0969-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyra, Heitor (1977). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Declínio (1880–1891) (in Portuguese). 3. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Martins, Luís (2008). O patriarca e o bacharel (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Alameda.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mônaco Janotti, Maria de Lourdes (1986). Os Subversivos da República (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Brasiliense.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salles, Ricardo (1996). Nostalgia Imperial (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks. OCLC 36598004.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (1998). As barbas do Imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-7164-837-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Teive HA, Almeida SM, Arruda WO, Sá DS, Werneck LC (June 2001). "Charcot and Brazil" (PDF). Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 59 (2–A): 295–9. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2001000200032. PMID 11400048.

.svg.png.webp)