Eusauropoda

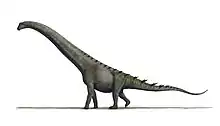

Eusauropoda (meaning "true sauropods") is a derived clade of sauropod dinosaurs. Eusauropods represent the node-based group that includes all descendant sauropods starting with the basal eusauropods of Shunosaurus, and possibly Barapasaurus, and Amygdalodon, but excluding Vulcanodon and Rhoetosaurus.[1] The Eusauropoda was coined in 1995 by Paul Upchurch to create a monophyletic new taxonomic group that would include all sauropods, except for the vulcanodontids.[2]

| Eusauropods | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull of Jobaria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Gravisauria |

| Clade: | †Eusauropoda Upchurch, 1995 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Eusauropoda are herbivorous, quadrupedal, and have long necks. They have been found in South America, Europe, North America, Asia, Australia, and Africa.[3] The temporal range of Eusauropoda ranges from the early Jurassic to the Latest Cretaceous periods.[1] The most basal forms of eusauropods are not well known and because the cranial material for the Vulcanodon is not available, and the distribution of some of these shared derived traits that distinguish Eusauropoda is still completely clear.[1][4]

Description

Eusauropods are long-necked, strictly herbivorous, obligate quadrupedals.[5] They have a highly specialized set of skeletal adaptions due to their large size, and are graviportal.[6]

Teeth and mouth

Yates and Upchurch described eusauropod evolution as moving towards a “bulk-browsing mode of feeding”. They describe the development of lateral plates on the alveolar margins of tooth-bearing bones. These plates can be used to strip foliage, the eusauropod's “U-shaped” jaws create a wide bite, and their loss of “fleshy cheeks” increased the gape.[6] The crowns of eusauropod teeth also have “wrinkled enamel textures”, but it is unclear what this meant for their feeding habits.[1]

Head and neck

The skull length of the basal eusauropod, Patagosaurus is about 60 centimetres (24 in).[7] One of the most basal eusauropods, Shunosaurus, has two characteristic features of the eusauropod elongated neck: the incorporation of the equivalent of the first dorsal vertebra into the cervical region of the spine, and the addition of two cervical vertebra in the middle of the cervical vertebrae.[4]

Other synapomorphies of Eusauropoda includes a retracted position of the external nares. Unlike prosauropods and theropods, which have a snout with smooth, unprotruding alveolar and subnarial regions, eusauropods have snouts with “stepped anterior margins”. Further distinguishing features of eusauropods include the absence of the contact between the squamosal and the quadratojugal, the absence of the anterior process of the prefrontal, and a distally elongated anterior ramus of the quadratojugal. Separating the anteroventral process of the nasal from the posterolateral process of the premaxilla, eusauropods also have a long maxilla that forms the posteroventral margin of the external naris.[1]

Feet and limbs

Eusauporoda are also hypothesized to have a semi-digitigrade foot posturem demonstrated by footprint evidence.[4] Paleontologist Jeffrey Wilson explains that eusauropods differ from theropods and prosauropods that have digitigrade pes where their heel and metatarsals are lifted off the ground. Eusauropods show asymmetry in their metatarsal shaft diameters where metatarsal I is broader than the others, suggesting that their weight was mostly assumed by their inner feet.[1] According to Steven Salisbury and Jay Nair, basal eusauropods retain four pedal unguals but reduce their phalangeal number in their fourth digit to three units.[8] The metatarsus in eusauropods is less than a quarter of their tibial length, unlike sauropod outgroups that have long hindlimbs and metatarsus that are almost half of their tibial length.[4]

Distribution

Eusauropods are found on all major continents, except Antarctica, with diplocodoids being widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, and titanosaurs being found in Southern Hemisphere. However, basal eusauropods that do not fall into either group are fairly well represented.[9]

Early eusauropods such as Volkeimeria and Amygdalodon, and more derived eusauropods such as Patagosaurus have been found in South America.[7] Volkeimeria is classified as a basal eusauropod, though in 2004 Paul Upchurch was suspicious of its placement, because of its “opisthoceolous cervical centra, the absence of a femoral anterior trochanter, and laterally projecting cnemial crest of the tibia”, and instead thought it may be a generic sauropod.[9]

African eusauropods may include Spinophorosaurus, from Niger, although that taxon may instead be closer to Vulcanodon and outside Eusauropoda.[3][8] Also, Atlasaurus was found in Morocco, and Jobaria was found in Niger. However, both genera have been found as possible Macronarians, but Atlasaurus was found to be a turiasaurian, and Jobaria a eusauropod, by a phylogenetic analysis of Xing in 2012.[3][9]

In Europe, the clade Turiasauria has been found in France, Spain, and possibly England, with multiple genera from the same locality in Spain.[9][10] Cetiosaurus skeletons have also been found in England, along with the possibly eusauropod genera Cardiodon and Oplosaurus, known only from teeth.[9]

The family Mamenchisauridae is found widespread throughout Asia. A majority of the genera are found in China, although a possible specimen of Mamenchisaurus has been found in Thailand.[3][9] Also in China, the basal eusauropod Nebulasaurus taito was found to be a sister taxon to Spinophorosaurus, and more derived than Mamenchisauridae, but less derived than Patagosaurus, and the genus Shunosaurus is likely one of the most basal eusauropods.[3][9] The genus Barapasaurus has been found in India, and may represent a cetiosaurid, a basal eusauropod, or a genus outside Eusauropoda.[3][8][9]

Paleobiology

The data around sauropods evolution, as Novas points out, is largely based on a few formations mostly in the Northern Hemisphere. However, other beds in places such as Tanzania, specifically the Canadon Asfalto and Canadon Calcereo formations reveal a more diverse and widespread peleobiology of eusauropods in the Late Jurassic period.[7]

Classification

The following cladogram demonstrates hypothesized relationships within the Eusauropoda.. The basal eusauropods include the Turiasauria (Turiasaurus, Zby and others.[11]

| Eusauropoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Wilson, J.A.; Curry-Rogers, K.A. (2005). The Sauropods: evolution and paleobiology. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24623-2.

- Upchurch, P (1995). "The evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 349 (1330): 365–390. Bibcode:1995RSPTB.349..365U. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0125.

- Xing, Lida (2013). "A new basal eusauropod from the Middle Jurassic of Yunnan, China, and faunal compositions and transitions of Asian sauropodomorph dinosaurs". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0151.

- Wilson, J.A.; Sereno, P.C. (1998). "Early Evolution and Higher-Level Phylogeny of Sauropod Dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (2): 1–79. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011115.

- Taylor, M.P.; Wedel, M.J. (2013). "Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks". PeerJ. 1: e36. doi:10.7717/peerj.36. PMC 3628838. PMID 23638372.

- Yates, A.M.; Bonnan, M.F.; Neveling, J.; Chinsamy, A.; Blackbeard, M.G. (2009). "A new transitional sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and the evolution of sauropod feeding and quadrupedalism". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1682): 787–794. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1440. PMC 2842739. PMID 19906674.

- Novas, F.E. (2009). The age of dinosaurs in South America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35289-7.

- Nair, J.P.; Salisbury, S.W. (2012). "New anatomical information on Rhoetosaurus Longman, 1926, a gravisaurian sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Queensland, Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (2): 369–394. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.622324.

- Upchurch, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, D.B.; Osmolska, H.; Dodson, P. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. pp. 261–299. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Luque, L.; Aberasturi, A.; Espilez, E.; Fierro, I.; Gonzalez, A.; Mampel, L.; Alcala, L. (September 2009). "High European sauropod dinosaur diversity during Jurassic-Cretaceous transition in Riodeva (Teruel, Spain)". Palaeontology. 52 (5): 1009–1027. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00898.x.

- Mateus, Octávio; Mannion, Philip D.; Upchurch, Paul (6 May 2014). "a new turiasaurian sauropod (Dinosauria, Eusauropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (3): 618–634. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.822875.