Alamosaurus

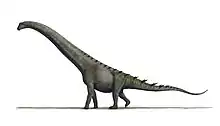

Alamosaurus (/ˌæləmoʊˈsɔːrəs/;[1] meaning "Ojo Alamo lizard") is a genus of potentially opisthocoelicaudiine titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs, containing a single known species, Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, from the late Cretaceous Period of what is now southern North America. Isolated vertebrae and limb bones indicate that it reached sizes comparable to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus, which would make it the largest dinosaur known from North America.[2] Its fossils have been recovered from a variety of rock formations spanning the Maastrichtian age of the late Cretaceous period. Specimens of a juvenile Alamosaurus sanjuanensis have been recovered from only a few meters below the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary in Texas, making it among the last surviving non-avian dinosaur species.[3]

| Alamosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restored skeletons of Alamosaurus and Tyrannosaurus at Perot Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Eusauropoda |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Lithostrotia |

| Family: | †Saltasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Opisthocoelicaudiinae |

| Genus: | †Alamosaurus Gilmore, 1922 |

| Type species | |

| †Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922 | |

Description

Alamosaurus was a gigantic quadrupedal herbivore with a long neck and tail and relatively long limbs.[3] Its body was at least partly covered in bony armor.[4] In 2012 Thomas Holtz gave a total length of 30 meters (98 ft) or more and an approximate weight of 72.5–80 tonnes (80–88 short tons) or more.[5][6] Though most of the complete remains come from juvenile or small adult specimens, three fragmentary specimens, SMP VP−1625, SMP VP−1850 and SMP VP−2104, suggest that adult Alamosaurus could have grown to enormous sizes comparable to the largest known dinosaurs like Argentinosaurus, which has been estimated to weigh 73 metric tons (80 short tons).[2] Scott Hartman estimates Alamosaurus, based on a huge incomplete tibia that probably refers to it, being slightly shorter at 28–30 m (92–98 ft) and equal in weight to other massive titanosaurs such as Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus.[7] However, he says that at the moment, scientists do not know whether the massive tibia belongs to an Alamosaurus or a completely new species of sauropod.[8] In 2019 Gregory S. Paul estimated the (SMP VP−1625) specimen at 27 tonnes (30 short tons), and he also mentioned a large partial anterior caudal vertebra which suggests an Alamosaurus specimen that is 15 percent dimensionally larger with similar mass to his Dreadnoughtus estimation of 31 tonnes (34 short tons).[9] In 2020 Molina-Perez and Larramendi estimated the size of the largest individual at 26 meters (85.3 ft) and 38 tonnes (42 short tons).[10]

Though no skull has ever been found, rod-shaped teeth have been found with Alamosaurus skeletons and probably belonged to this dinosaur.[3] The vertebrae from the middle part of its tail had elongated centra.[11] Alamosaurus had vertebral lateral fossae that resembled shallow depressions.[11] Fossae that similarly resemble shallow depressions are known from Saltasaurus, Malawisaurus, Aeolosaurus, and Gondwanatitan.[11] Venenosaurus also had depression-like fossae, but its "depressions" penetrated deeper into the vertebrae, were divided into two chambers, and extend farther into the vertebral columns.[11] Alamosaurus had more robust radii than Venenosaurus.[11]

History

Alamosaurus remains have been discovered throughout the southwestern United States. The holotype was discovered in June 1921 by Charles Whitney Gilmore, John Bernard Reeside and Charles Hazelius Sternberg at the Barrel Springs Arroyo in the Naashoibito Member of the Ojo Alamo Formation (or Kirtland Formation under a different definition) of New Mexico which was deposited during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous Period.[12] Bones have also been recovered from other Maastrichtian formations, like the North Horn Formation of Utah and the Black Peaks, El Picacho and Javelina Formations of Texas.[13] Undescribed titanosaur fossils closely associated with Alamosaurus have been found in the Evanston Formation in Wyoming. Three articulated caudal vertebrae were collected above Hams Fork, and are housed at the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley. These specimens have not been described.[14]

Smithsonian paleontologist Gilmore originally described the holotype, USNM 10486, a left scapula (shoulder bone), and the paratype USNM 10487, a right ischium (pelvic bone) in 1922, naming the type species Alamosaurus sanjuanensis. Contrary to popular assertions, the dinosaur is not named after the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas, or the battle that was fought there.[15] The holotype, the specimen the name was based on, was discovered in New Mexico and, at the time of its naming, Alamosaurus had not yet been found in Texas. Instead, the name Alamosaurus comes from Ojo Alamo, the geologic formation in which it was found and which was, in turn, named after the nearby Ojo Alamo trading post (since this time there has been some debate as to whether to reclassify the Alamosaurus-bearing rocks as belonging to the Kirtland Formation or whether they should remain in the Ojo Alamo Formation). The term alamo itself is a Spanish word meaning "poplar" and is used for the local subspecies of cottonwood tree. The term saurus is derived from saura (σαυρα), Greek for "lizard" and is the most common suffix used in dinosaur names. There is only one species in the genus, Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, which is named after San Juan County, New Mexico, where the first remains were found.[12]

In 1946, Gilmore posthumously described a more complete specimen, USNM 15660 found on June 15, 1937 on the North Horn Mountain of Utah by George B. Pearce. It consists of a complete tail, a right forelimb complete except for the fingers — which later research showed do not ossify with the Titanosauridae — and both ischia.[16] Since then, hundreds of other bits and pieces from Texas, New Mexico, and Utah have been referred to Alamosaurus, often without much description. Despite being fragmentary, until the second half of the twentieth century they represented much of the globally known titanosaurid material. The most completely known specimen, TMM 43621-1, is a recently discovered juvenile skeleton from Texas, which allowed educated estimates of length and mass.[3]

Some blocks catalogued under the same accession number as the relatively complete and well-known Alamosaurus specimen USNM 15660, and found in very close proximity to it based on bone impressions, were first investigated by Michael Brett-Surman in 2009. In 2015, he reported that the blocks contained osteoderms, the first confirmation of their existence on Alamosaurus.[4]

No skull material is known, except for a few slender teeth.[13]

The restored Alamosaurus skeletal mount at the Perot Museum [17] (pictured right) was discovered when a member of an excavation team at a nearby site had to go around a hill to urinate.[18]

Classification

Gilmore in 1922 was uncertain about the precise affinities of Alamosaurus and did not determine it any further than a general Sauropoda.[12] In 1927 Friedrich von Huene placed it in the Titanosauridae.[19]

Alamosaurus was in any case an advanced, or derived, member of the group Titanosauria, but its relationships within that group are far from certain. The issue is further complicated by some researchers rejecting the name Titanosauridae and replacing it with Saltasauridae. One major analysis unites Alamosaurus with Opisthocoelicaudia in a subgroup Opisthocoelicaudinae of the Saltasauridae.[20] A major competing analysis finds Alamosaurus as a sister taxon to Pellegrinisaurus, with both genera located just outside Saltasauridae.[21] Other scientists have also noted particular similarities with the saltasaurid Neuquensaurus and the Brazilian Trigonosaurus (the "Peiropolis titanosaur") which is used in many cladistic and morphologic analyses of titanosaurians.[3] A recent analysis published in 2016 by Anthony Fiorillo and Ron Tykoski indicates that Alamosaurus was a sister taxon to the Lognkosauria and therefore to species such as Futalognkosaurus and Mendozasaurus and lay outside the Saltasauridae (possibly being descended from close relations to the Saltasauridae), based on synapomorphies of cervical vertebral morphologies and two cladistic analyses.[22] The same study also suggests that the ancestors of Alamosaurus hailed from South America, rather than Asia.[23]

Age

Alamosaurus fossils are most notably found in the Naashoibito member of the Ojo Alamo Formation (dated to between about 69–68 million years old) and in the Javelina Formation, though the exact age range of the latter has been difficult to determine.[24] A juvenile specimen of Alamosaurus has been reported to come from the Black Peaks Formation, which overlies the Javelina in Big Bend, Texas, and which straddles the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. The Alamosaurus specimen was reported to come from a few meters below the boundary, dated to 66 million years ago, though the position of the boundary in this region is uncertain.[3] Only one geological site in the Javelina Formation has thus far yielded the correct rock types for radiometric dating. The outcrop, situated in the middle strata of the formation about 90 meters (300 ft) below the K-Pg boundary and within the local range of Alamosaurus fossils, was dated to 69.0±0.9 million years old in 2010.[25] Using this date, in correlation with a measured age from the underlying Aguja Formation and the likely location of the K-Pg boundary in the overlying Black Peaks Formation, the Alamosaurus fauna seems to have lasted from about 70–66 million years ago, with the earliest records of Alamosaurus near the base of the Javelina formation, and the latest just below the K-Pg boundary in the Black Peaks Formation.[25]

Habitat and geographic origin

Skeletal elements of Alamosaurus are among the most common Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils found in the United States Southwest and are now used to define the fauna of that time and place, known as the "Alamosaurus fauna". In the south of Late Cretaceous North America, the transition from the Edmontonian to the Lancian faunal stages is even more dramatic than it was in the north. Thomas M. Lehman describes it as "the abrupt reemergence of a fauna with a superficially 'Jurassic' aspect."[26] These faunas are dominated by Alamosaurus and feature abundant Quetzalcoatlus in Texas.[26] The Alamosaurus-Quetzalcoatlus association probably represent semi-arid inland plains.[26]

The appearance of Alamosaurus may have represented an immigration event from South America.[26] Alamosaurus appears and achieves dominance in its environment very abruptly, which might support the idea that it originated following an immigration event.[26] Other scientists speculated that Alamosaurus was an immigrant from Asia.[26] However, critics of the immigration hypothesis note that inhabitants of an upland environment like Alamosaurus are more likely to be endemic than coastal species, and tend to have less of an ability to cross bodies of water.[26] Further, Early Cretaceous titanosaurs are already known, so North American potential ancestors for Alamosaurus already existed.[26]

Contemporaries of Alamosaurus in the American southwest include the tyrannosaurid Tyrannosaurus, the oviraptorid Ojoraptorsaurus, the hadrosaurids Gryposaurus alsatei and cf. Kritosaurus, the armored nodosaur Glyptodontopelta and the chasmosaurine ceratopsids cf. Torosaurus utahensis, Bravoceratops, and Ojoceratops. Non-dinosaur taxa that had shared the same environment with Alamosaurus include the giant pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus, various species of fishes and rays, amphibians, lizards, turtles like Adocus, and multiple species of multituberculates like Cimexomys and Mesodma.

References

- "Alamosaurus". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- Fowler, D. W.; Sullivan, R. M. (2011). "The First Giant Titanosaurian Sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 685. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.3759. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0105. S2CID 53126360.

- Lehman, T.M.; Coulson, A.B. (2002). "A juvenile specimen of the sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis from the Upper Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 76 (1): 156–172. doi:10.1017/s0022336000017431.

- Carrano, M.T.; D'Emic, M.D. (2015). "Osteoderms of the titanosaur sauropod dinosaur Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (1): e901334. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.901334. S2CID 86797277.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- Holtz Jr., Thomas R. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages".

- http://www.skeletaldrawing.com/home/2013/6/21/assessing-alamosaurus?rq=alamosaurus

- http://www.skeletaldrawing.com/home/2013/06/the-biggest-of-big.html?rq=alamosaurus

- Paul, Gregory S. (2019). "Determining the largest known land animal: A critical comparison of differing methods for restoring the volume and mass of extinct animals" (PDF). Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 335–358. doi:10.2992/007.085.0403. S2CID 210840060.

- Molina-Perez & Larramendi (2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 268.

- Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K. & Meyer, S. 2001. New Titanosauriform (Sauropoda) from the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Utah. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. D. H. Tanke & K. Carpenter (eds.). Indiana University Press, Eds. D.H. Tanke & K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press. 139–165.

- Gilmore, C.W. (1922). "A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 72 (14): 1–9.

- Weishampel, D.B. et al.. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution (Late Cretaceous, North America)". In Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Oslmolska, H. (eds.). "The Dinosauria (Second ed.)". University of California Press.

- Lucas and Hunt, Spencer G. and Adrian P. (1989). Farlow, James O. (ed.). "Alamosaurus and the Sauropod Hiatus in the Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior". Paleobiology of the Dinosaurs. Geological Society of America Special Papers. 238 (238): 75–86. doi:10.1130/SPE238-p75. ISBN 0-8137-2238-1.

- Anthony D. Fredericks, 2012, Desert Dinosaurs: Discovering Prehistoric Sites in the American Southwest, The Countryman Press, p. 102-103

- Gilmore, C.W. 1946. Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of central Utah. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. 210-C:29–51.

- Perot Museum of Nature and Science

- https://www.perotmuseum.org/exhibits-and-films/permanent-exhibit-halls/life-then-and-now-hall.html

- v. Huene, F. (1927). "Sichtung der Grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der Sauropoden". Eclogae Geologicae Helveticae. 20: 444–470.

- Wilson, J.A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136 (2): 217–276. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- Upchurch, P., Barrett, P.M. & Dodson, P. 2004. Sauropoda. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 259–322.

- Tykoski, Ronald S.; Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2017). "An articulated cervical series of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from Texas: new perspective on the relationships of North America's last giant sauropod". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 15 (5): 1–26. doi:10.1080/14772019.2016.1183150.

- "Blogs". PLOS. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- Sullivan, R.M., and Lucas, S.G. 2006. "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age" – faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America." New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 35:7–29.

- Lehman, T. M.; Mcdowell, F. W.; Connelly, J. N. (2006). "First isotopic (U-Pb) age for the Late Cretaceous Alamosaurus vertebrate fauna of West Texas, and its significance as a link between two faunal provinces". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 922–928. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[922:fiuaft]2.0.co;2.

- Lehman, T. M., 2001, Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 310–328.