Elasmotherium

Elasmotherium is an extinct genus of large rhinoceros endemic to Eurasia during the Late Pliocene through the Pleistocene, existing from 2.6 Ma to at least as late as 39,000 years ago in the Late Pleistocene.[2] A more recent date of 26,000 BP is considered less reliable.[2] It was the last surviving member of Elasmotheriinae, a distinctive group of rhinoceroses that had separated from the ancestry of living rhinoceroses by at least 35 million years ago according to fossils and estimated around 47.4 million years ago based on molecular clock.[2]

| Elasmotherium | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Reconstructed E. caucasicum skeleton, Azov History, Archaeology and Paleontology Museum-Reserve | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Subfamily: | †Elasmotheriinae |

| Genus: | †Elasmotherium J. Fischer, 1808[1] |

| Species | |

| |

| |

| Approximate range map for Elasmotherium | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Four species are recognised, which were largely confined to the Pontic–Caspian steppe, the Caucasus and Central Asia.[3] The best known, E. sibiricum, known as the Siberian unicorn,[4] was the size of a mammoth and is thought to have borne a large, thick horn on its forehead. Like all rhinoceroses, elasmotheres were herbivorous. Unlike any other rhinos and any other ungulates aside from some notoungulates, its high-crowned molars were ever-growing. Its legs were longer than those of other rhinos and were adapted for galloping, giving it a horse-like gait.

Taxonomy

Elasmotherium was first described in 1809 by German/Russian palaeontologist Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim based on a left lower jaw, four molars, and the tooth root of the third premolar, which was gifted to Moscow University by princess Ekaterina Dashkova in 1807. He first announced it at an 1808 presentation before the Moscow Society of Naturalists.[5] The genus name derives from Ancient Greek elasmos "laminated" and therion "beast" in reference to the laminated folding of the tooth enamel; and the species name sibericus is probably a reference to the predominantly Siberian origin of princess Dashkova's collection. However, the specimen's exact origins are unknown. In 1877, German naturalist Johann Friedrich von Brandt placed it into the newly erected subfamily Elasmotheriinae, separate from modern rhinos.[6] In 1997, the McKenna/Bell classification considered Elasmotherium to be closely related to the wooly and modern rhinos, and placed it into the subfamily Rhinocerotinae. A complete mitochondrial genome obtained from a specimen of E. sibiricum vindicated von Brandt, finding it to be the sister taxon to all living rhinoceroses, with an estimated divergence time of 47.4 million years ago, with a 95% highest posterior density of 41.9–53.2 Ma.[2]

The genus is known from hundreds of find sites, mainly of cranial fragments and teeth, but in some cases nearly complete skeletons of post-cranial bones, scattered over Eurasia from Eastern Europe to China.[7] Dozens of crania have been reconstructed and given archaeological identifiers. The division into species is based mainly on the fine distinctions of the teeth and jaws and the shape of the skull.[8]

Species

There are four chronospecies of Elasmotherium which are in from oldest to youngest E. chaprovicum, E. peii, E. caucasicum and E. sibiricum, which span from the Late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene.[3]

An elasmotherian species turned up in the preceding Khaprovian or Khaprov Faunal Complex, which was at first taken to be E. caucasicum,[9] and then on the basis of the dentition was redefined as a new species, E. chaprovicum (Shvyreva, 2004), named after the Khaprov Faunal Complex.[8] The Khaprov is in the Middle Villafranchian, MN17, which spans the Piacenzian of the Late Pliocene and the Gelasian of the Early Pleistocene of Northern Caucasus, Moldova and Asia and has been dated to 2.6–2.2 Ma.[10]

E. peii was first described by (Chow, 1958) for remains found in Shaanxi, China.[11] Additional remains from Shaanxi were described in 2018[12] The species is also known from numerous remains from the classical range of Elasmotherium, some sources have considered this species to be a synonym of E. caucasicum, but it is currently considered distinct.[3] it is found during the Psekups faunal complex between 2.2 and 1.6 Ma.[3]

E. caucasicum was first described by Russian palaeontologist Aleksei Borissiak in 1914, who said it apparently flourished in the Black Sea region as a member of the Early Pleistocene Tamanian Faunal Unit (1.1–0.8 Ma, Taman Peninsula). It is the most commonly found mammal of the assemblage. E. caucasicum is thought to be more primitive than E. sibiricum and perhaps represents an ancestral stock.[13][14] It is also known in northern China from the Early Pleistocene Nihewan Faunal assemblage and were extinct at approximately 1.6 Ma. This suggests Elasmotherium developed separately in Russia and China.[15]

E. sibiricum, described by Johann Fischer von Waldheim in 1808 and chronologically the latest species of the sequence appeared in the Middle Pleistocene, ranging from southwestern Russia to western Siberia and southward into Ukraine and Moldova.[16]

Evolution

Rhinoceroses are divided into two subfamilies, Rhinocerotinae and Elasmotheriinae, which diverged perhaps 47.3 mya, 35 mya at the latest.[2] Elasmotherium is the only known member of the latter from after the Miocene, others becoming extinct with the expansion of savannas.[17] Elasmotherium appeared in the Late Pliocene, apparently deriving from the Miocene—Pliocene Sinotherium. However, a 1995 cladistic analysis asserted that Elasmotherium was most closely related to the woolly rhino, a rhinocerotine.[17]

Hypsodonty, a dentition pattern where the molars have high crowns and the enamel extends below the gum line, is thought to be a characteristic of Elasmotheriinae,[18] perhaps as an adaptation to the heavier grains featured in riparian zones on riversides.[15]

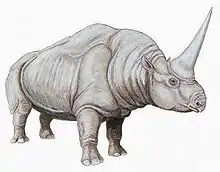

Description

Elasmotherium is typically reconstructed as a woolly animal, generally based on the woolliness exemplified in contemporary megafauna such as mammoths and the woolly rhino. However, it is sometimes depicted as bare-skinned like modern rhinos. In 1948, Russian palaeontologist Valentin Teryaev suggested it was semi-aquatic with a dome-like horn, and resembled a hippo because the animal had 4 toes like a wetland tapir rather than the 3 toes in other rhinos, but Elasmotherium has since been shown to have had only 3 functional toes,[6] and Teryaev's reconstruction has not garnered much scientific attention.[6][15]

The known specimens of E. sibiricum reach up to 4.5 m (15 ft) in length, with shoulder heights of over 2 m (6 ft 7 in), while E. caucasicum reaches at least 5 m (16 ft) in body length with an estimated mass of 3.6–4.5 tonnes (4–5 short tons),[6] making Elasmotherium the largest rhinos of the Quaternary.[2] Both species were among the largest rhinos, comparable in size to the woolly mammoth and larger than the contemporary woolly rhinoceros.[19][17] The feet were unguligrade, the front larger than the rear, with 3 digits at the front and rear, with a vestigial fifth metacarpal.[20]

Dentition

Like other rhinos, Elasmotherium had two premolars and three molars for chewing, and lacked incisors and canines, relying instead on a prehensile lip to strip food.[6] Elasmotherium were euhypsodonts, with large tooth crowns and enamel extending below the gum line, and continuously growing teeth.

Elasmotherium fossils rarely show evidence of tooth roots.

Horn

Elasmotherium is thought to have had a keratinous horn, indicated by a circular dome on the forehead, with a 5-inch (13 cm) deep, furrowed surface, and a circumference of 3 feet (0.91 m). The furrows are interpreted as the seats of blood vessels for horn-generating tissue.[21][22]

In rhinos, the horn is not attached to bone, but grows from the surface of a dense skin tissue, anchoring itself by creating bone irregularities and rugosities.[23] The outermost layer cornifies.[24] As the layers age, the horn loses diameter by degradation of the keratin due to ultraviolet light, drying out, and continual wearing.[25] However, melanin and calcium deposits in the centre harden the keratin there, which gives the horn its distinctive shape.[26]

There was likely a large hump of muscle on the back, which is generally thought to have supported a heavy horn.[27]

Palaeobiology

Diet

Modern hypsodont hoofed mammals are generally grazers of open environments,[28] with hypsodonty possibly an adaptation to chewing tough, fibrous grass.[29] Elasmotherium dental wearing is similar to that of the grazing white rhino,[30] and both of their heads have a downward orientation, indicating a similar lifestyle and an ability to only reach low-lying plants. In fact, the head of Elasmotherium had the most obtuse angle of any rhinoceros, and could only reach the lowest levels and therefore must have grazed habitually.[22] Elasmotherium also displays euhypsodonty, which is typically seen in rodents,[31] and dental physiology could have been influenced by pulling up food from moist, grainy soil. Therefore, they may have inhabited both mammoth steppeland and riparian riversides, similar to contemporary mammoths.[15]

Movement

Elasmotherium had similar running limbs to the white rhinoceros–which run at 30 km/h (19 mph) with a top speed of 40–45 km/h (25–28 mph). However, Elasmotherium had double the weight–about 5 t (5.5 short tons)–and consequently had a more restricted gait and mobility, likely achieving much slower speeds. Elephants, weighing 2.5–11 t (2.8–12.1 short tons), cannot exceed a speed of 20 km/h (12 mph).[32]

Extinction

Elasmotherium was previously thought to have gone extinct around 200 kya as part of normal extinction,[2] but E. sibiricum skull fragments from the Pavlodar Region, Kazakhstan, shows its persistence in the Western Siberian Plain about 36–35 kya.[2] Isolated remains dating to 50 kya are known from the Siberian Smelovskaya and Batpak Caves, likely dragged there by a predator.[33]

This timing is roughly coincident with the Pleistocene extinction, where anything over 45 kg (100 lb) went extinct, coinciding with a shift to a cooler climate–which resulted in replacement of grasses and herbs by lichens and mosses–and the migration of modern humans into the area.[2]

Notes

- "Elasmotherium". PaleoBiology Database: Basic info. National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. 2000. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Kosintsev, P.; Mitchell, K. J.; Devièse, T.; van der Plicht, J.; Kuitems, M.; Petrova, E.; Tikhonov, A.; Higham, T.; Comeskey, D.; Turney, C.; Cooper, A.; van Kolfschoten, T.; Stuart, A. J.; Lister, A. M. (2019). "Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0722-0. PMID 30478308. S2CID 53726338.

- Schvyreva, A.K. (August 2015). "On the importance of the representatives of the genus Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) in the biochronology of the Pleistocene of Eastern Europe". Quaternary International. 379: 128–134. Bibcode:2015QuInt.379..128S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.052.

- Kosintsev, Pavel; et al. (2019). "Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions". Nature Ecology and Evolution. 3 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0722-0. PMID 30478308. S2CID 53726338.

- Fischer, G. (1809). "Memoires de la Société Impériale des Naturalistes de Moscou". Tome II. Moscou: Imprimerie de l'Université Impériale: 255 (21. Sur L'Elasmotherium et le Trogontothérium). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Zhegallo, V.; Kalandadze, N.; Shapovalov, A.; Bessudnova, Z.; Noskova, N.; Tesakova, E. (2005). "On the fossil rhinoceros Elasmotherium (including the collections of the Russian Academy of Sciences)" (PDF). Cranium. 22 (1): 17–40.

- Tleuberdina, Piruza; Nazymbetova, Gulzhan (2010). "Distribution of Elasmotherium in Kazakhstan". In Titov, V.V.; Tesakov, A.S. (eds.). Quaternary stratigraphy and paleontology of the Southern Russia: connections between Europe, Africa and Asia: Abstracts of the International INQUA-SEQS Conference (Rostov-on-Don, June 21–26, 2010) (PDF). Rostov-on-Don: Russian Academy of Science. pp. 171–173. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- Titov, V.V. (2008). Late Pliocene large mammals from Northeastern Sea of Azov Region (PDF) (in Russian and English). Rostov-on-Don: SSC RAS Publishing.

- Logvynenko, Vitaliy. "The Development of the Late Pleistocene to Early Middle Pleistocene Large Mammal Fauna of Ukraine" (PDF). 18th International Senckenberg Conference 2004 in Weimar (Abstracts). Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN).

- Bajgusheva, Vera S.; Titov, Vadim V. "Results of the Khapry Faunal Unit revision" (PDF). 18th International Senckenberg Conference 2004 in Weimar (Abstracts). Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN).

- Chow, M.C., 1958. New elasmotherine Rhinoceroses from Shansi. Vertebrato PalA-siatica 2, 135-142.

- Tong, Hao‑wen; Chen, Xi; Zhang, Bei (1 September 2018). "New postcranial bones of elasmotherium peii from shanshenmiaozui in Nihewan basin, Northern China". Quaternaire (vol. 29/3): 195–204. doi:10.4000/quaternaire.10010. ISSN 1142-2904.

- Deng & Zheng 2005, p. 119

- Deng & Zheng 2005, p. 112

- Noskova, N.G. (2001). "Elasmotherians – evolution, distribution and ecology". In Cavarretta, G.; Gioia, P.; Mussi, M.; et al. (eds.). The World of Elephants (PDF). Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-88-8080-025-5.

- Baigusheva, Vera; Titov, Vadim (2010). "Pleistocene Large Mammal Associations of the Sea of Azov and Adjacent Regions". In Titov, V.V.; Tesakov, A.S. (eds.). Quaternary stratigraphy and paleontology of the Southern Russia: connections between Europe, Africa and Asia: Abstracts of the International INQUA-SEQS Conference (Rostov-on-Don, June 21–26, 2010) (PDF). Rostov-on-Don: Russian Academy of Science. pp. 24–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- Cerdeño, Esperenza (1998). "Diversity and evolutionary trends of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)" (PDF). Palaeo. 141 (1–2): 13–34. Bibcode:1998PPP...141...13C. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00003-0.

- Antoine 2003, p. 109

- Cerdeño, Esperanza; Nieto, Manuel (1995). "Changes in Western European Rhinocerotidae related to climatic variations" (PDF). Palaeo. 114 (2–4): 328. Bibcode:1995PPP...114..325C. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)00085-M.

- Belyaeva, E.I. (1977). "About the Hyroideum, Sternum and Metacarpale V Bones of Elasmotherium sibiricum Fischer (Rhinocerotidae)" (PDF). Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India. 20: 10–15.

- Brandt, Alexander; Lockyer, Norman (8 August 1878). "The Elasmotherium". Nature. XVIII (458): 287–389. Bibcode:1878Natur..18R.387.. doi:10.1038/018387b0.

- van der Made, Jan; Grube, René (2010). "The rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and their nutrition". In Meller, Harald (ed.). Elefantenreich – Eine Fossilwelt in Europa (PDF). Halle/Saale. pp. 382–394.

- Hieronymus 2009, pp. 221–223

- Hieronymus 2009, p. 24

- Hieronymus 2009, p. 27

- Hieronymus 2009, p. 28

- Hieronymus 2009, p. 36

- Mendoza, M.; Palmqvist, P. (February 2008). "Hypsodonty in ungulates: an adaptation for grass consumption or for foraging in open habitat?". Journal of Zoology. 273 (2): 134–142. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00365.x.

- MacFadden, Bruce J. (2000). "Origin and evolution of the grazing guild in Cenozoic New World terrestrial mammals". In Sues, Hans-Dieter (ed.). Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates: Perspectives from the Fossil Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 226.

- Wood, Horace Elmer, 2nd (1938). "Causal Factors Shortening Tooth Series with Age". Journal of Dental Research. 17 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1177/00220345380170010101. S2CID 209330196.

- von Koenigswald, Wighart; Goin, Francisco; Pascual, Rosendo (1999). "Hypsodonty and enamel microstructure in the Paleocene gondwanatherian mammal Sudamerica amerghinoi" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 44 (3): 263–300.

- Paul, Gregory S. (December 1998). "Limb Designs, Function and Running Performance in Ostrich-mimics and Tyrannosaurs" (PDF). Gaia (15): 258–259. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- Kosintsev, Pavel (2010). "Relict Mammal Species of the Middle Pleistocene in Late Pleistocene Fauna of the Western Siberia South". In Titov, V.V.; Tesakov, A.S. (eds.). Quaternary stratigraphy and paleontology of the Southern Russia: connections between Europe, Africa and Asia: Abstracts of the International INQUA-SEQS Conference (Rostov-on-Don, June 21–26, 2010) (PDF). Rostov-on-Don: Russian Academy of Science. pp. 78–79. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

References

- Antoine, Pierre-Olivier (March 2003). "Middle Miocene elasmotheriine Rhinocerotidae from China and Mongolia: taxonomic revision and phylogenetic relationships" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 32 (2): 95–118. doi:10.1046/j.1463-6409.2003.00106.x.

- Deng, Tao; Zheng, Min (2005). "Limb Bones of Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) from Nihewan (Hebei, China)" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica (in Chinese and English) (4): 110–121.

- Hieronymus, Tobin L. (2009). Osteological Correlates of Cephalic Skin Structures in Amniota: Documenting the Evolution of Display and Feeding Structures with Fossil Data (Doctoral Thesis). College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University.

- Russell, James R. (2009). "From Zoroastrian Cosmology and Armenian heresiology to the Russian novel". In Allison, Christine; Joristen-Pruschke, Anke; Wendtland, Antje (eds.). From Daēnā to Dîn: Religion, Kultur und Sprache in der iranischen Welt; Festschrift für Philip Kezenbroek zum 60. Geburstag. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 141–208.

- Sinon, Denis (1960). "Sur les noms altaïque de la licorne" (PDF). Wiener Zeitschrift für der Kunde des Morgenlandes (in French) (56): 168–176.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elasmotherium. |

- Piper, Ross (2010). "Elasmotherium and the case of the massive horn". Scrubmuncher's Blog. Nature Blog Network. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Strauss, Bob. "Elasmotherium – About.com Prehistoric Mammals". Dinosaurs at About.com. About.com. Retrieved 30 August 2013.