Eclampsia

Eclampsia is the onset of seizures (convulsions) in a woman with pre-eclampsia.[1] Pre-eclampsia is a disorder of pregnancy in which there is high blood pressure and either large amounts of protein in the urine or other organ dysfunction.[8][9] Onset may be before, during, or after delivery.[1] Most often it is during the second half of pregnancy.[1] The seizures are of the tonic–clonic type and typically last about a minute.[1] Following the seizure there is typically either a period of confusion or coma.[1] Complications include aspiration pneumonia, cerebral hemorrhage, kidney failure, pulmonary oedema, HELLP syndrome, coagulopathy, abruptio placentae and cardiac arrest.[1][10] Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are part of a larger group of conditions known as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.[1]

| Eclampsia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Symptoms | Seizures, high blood pressure[1] |

| Complications | Aspiration pneumonia, cerebral hemorrhage, kidney failure, cardiac arrest[1] |

| Usual onset | After 20 weeks of pregnancy[1] |

| Risk factors | Pre-eclampsia[1] |

| Prevention | Aspirin, calcium supplementation, treatment of prior hypertension[2][3] |

| Treatment | Magnesium sulfate, hydralazine, emergency delivery[1][4] |

| Prognosis | 1% risk of death[1] |

| Frequency | 1.4% of deliveries[5][6] |

| Deaths | 46,900 hypertensive diseases of pregnancy (2015)[7] |

Recommendations for prevention include aspirin in those at high risk, calcium supplementation in areas with low intake, and treatment of prior hypertension with medications.[2][3] Exercise during pregnancy may also be useful.[1] The use of intravenous or intramuscular magnesium sulfate improves outcomes in those with eclampsia and is generally safe.[4][11] This is true in both the developed and developing world.[4] Breathing may need to be supported.[1] Other treatments may include blood pressure medications such as hydralazine and emergency delivery of the baby either vaginally or by cesarean section.[1]

Pre-eclampsia is estimated to affect about 5% of deliveries while eclampsia affects about 1.4% of deliveries.[5] In the developed world rates are about 1 in 2,000 deliveries due to improved medical care.[1] Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are one of the most common causes of death in pregnancy.[12][13] They resulted in 46,900 deaths in 2015.[7] Around one percent of women with eclampsia die.[1] The word eclampsia is from the Greek term for lightning.[14] The first known description of the condition was by Hippocrates in the 5th century BC.[14]

Signs and symptoms

Eclampsia is a disorder of pregnancy characterized by seizures in the setting of pre-eclampsia.[15] Pre-eclampsia is diagnosed when repeated blood pressure measurements are greater or equal to 140/90mmHg, in addition to any signs of organ dysfunction, including: proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, renal insufficiency, impaired liver function, pulmonary edema, cerebral symptoms, or abdominal pain.[16]

Typically the pregnant woman develops hypertension and proteinuria before the onset of a convulsion (seizure).[17]

- Long-lasting (persistent) headaches

- Blurred vision

- Photophobia (i.e. bright light causes discomfort)

- Abdominal pain

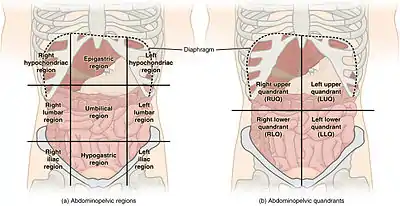

- Either in the epigastric region (the center of the abdomen above the navel, or belly-button)

- And/or in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (below the right side of the rib cage)

- Altered mental status (confusion)

Any of these symptoms may present before or after a seizure occurs.[18] It is also possible that none of these symptoms will develop.

Other cerebral signs may immediately precede the convulsion, such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, and cortical blindness. If the complication of multi-organ failure ensues, signs and symptoms of those failing organs will appear, such as abdominal pain, jaundice, shortness of breath, and diminished urine output.

Onset

The seizures of eclampsia typically present during pregnancy and prior to delivery (the antepartum period),[19] but may also occur during labor and delivery (the intrapartum period) or after the baby has been delivered (the postpartum period).[15][18][20] If postpartum seizures develop, it is most likely to occur within the first 48 hours after delivery. However, late postpartum seizures of eclampsia may occur as late as 4 weeks after delivery.[15][18]

Complications

There are risks to both the mother and the fetus when eclampsia occurs. The fetus may grow more slowly than normal within the womb (uterus) of a woman with eclampsia, which is termed intrauterine growth restriction and may result in the child appearing small for gestational age or being born with low birth weight.[21] Eclampsia may cause problems with the placenta to occur. The placenta may bleed (hemorrhage) or it may begin to separate from the wall of the uterus.[22][23] It is normal for the placenta to separate from the uterine wall during delivery, but it is abnormal for it to separate prior to delivery; this condition is called placental abruption and can be dangerous for the fetus.[24] Placental insufficiency may also occur, a state in which the placenta fails to support appropriate fetal development because it cannot deliver the necessary amount of oxygen or nutrients to the fetus.[22] During an eclamptic seizure, the beating of the fetal heart may become slower than normal (bradycardia).[21][25] If any of these complications occurs, fetal distress may develop. Treatment of the mother's seizures may also manage fetal bradycardia.[26][27] If the risk to the health of the fetus or the mother is high, the definitive treatment for eclampsia is delivery of the baby. Delivery by cesarean section may be deemed necessary, especially if the instance of fetal bradycardia does not resolve after 10 to 15 minutes of resuscitative interventions.[26][28] It may be safer to deliver the infant preterm than to wait for the full 40 weeks of fetal development to finish, and as a result prematurity is also a potential complication of eclampsia.[22][29]

In the mother, changes in vision may occur as a result of eclampsia, and these changes may include blurry vision, one-sided blindness (either temporary due to amaurosis fugax or potentially permanent due to retinal detachment), or cortical blindness, which affects the vision from both eyes.[30][31] There are also potential complications in the lungs. The woman may have fluid slowly collecting in the lungs in a process known as pulmonary edema.[22] During an eclamptic seizure, it is possible for a person to vomit the contents of the stomach and to inhale some of this material in a process known as aspiration.[21] If aspiration occurs, the woman may experience difficulty breathing immediately or could develop an infection in the lungs later, called aspiration pneumonia.[18][32] It is also possible that during a seizure breathing will stop temporarily or become inefficient, and the amount of oxygen reaching the woman's body and brain will be decreased (in a state known as hypoxia).[18][33] If it becomes difficult for the woman to breathe, she may need to have her breathing temporarily supported by an assistive device in a process called mechanical ventilation. In some severe eclampsia cases, the mother may become weak and sluggish (lethargy) or even comatose.[31] These may be signs that the brain is swelling (cerebral edema) or bleeding (intracerebral hemorrhage).[22][31]

Risk factors

Eclampsia, like pre-eclampsia, tends to occur more commonly in first pregnancies.[34][35][36] Women who have long term high blood pressure before becoming pregnant have a greater risk of pre-eclampsia.[34][35] Furthermore, women with other pre-existing vascular diseases (diabetes or nephropathy) or thrombophilic diseases such as the antiphospholipid syndrome are at higher risk to develop pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.[34][35] Having a large placenta (multiple gestation, hydatidiform mole) also predisposes women to eclampsia.[34][35][37] In addition, there is a genetic component: a woman whose mother or sister had the condition is at higher risk than otherwise.[38] Women who have experienced eclampsia are at increased risk for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in a later pregnancy.[35] People of certain ethnic backgrounds can have an increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. The occurrence of pre-eclampsia was 5% in white, 9% in Hispanic, and 11% in African American women. Black women were also shown to have a disproportionately higher risk of dying from eclampsia.[39]

Mechanism

The presence of a placenta is required, and eclampsia resolves if it is removed.[40] Reduced blood flow to the placenta (placental hypoperfusion) is a key feature of the process. It is accompanied by increased sensitivity of the maternal vasculature to agents which cause constriction of the small arteries, leading to reduced blood flow to multiple organs. Vascular dysfunction-associated maternal conditions such as Lupus, hypertension, and renal disease, or obstetric conditions that increase placental volume without an increase in placental blood flow (such as twin pregnancy) can increase risk for pre-eclampsia.[41] Also, an activation of the coagulation cascade may lead to microthrombi formation, which can further impair blood flow. Thirdly, increased vascular permeability results in the shift of extracellular fluid from the blood to the interstitial space, with further reduction in blood flow, and edema. These events lead to hypertension; renal, pulmonary, and hepatic dysfunction; and cerebral edema with cerebral dysfunction and convulsions.[40] Before symptoms appear, increased platelet and endothelial activation may be detected.[40]

Placental hypoperfusion is linked to abnormal modelling of the fetal–maternal placental interface that may be immunologically mediated.[40] Pre-eclampsia’s pathogenesis is poorly understood, but it likely is attributed to factors related to the mother and placenta, because pre-eclampsia is seen in molar pregnancies absent of a fetus or fetal tissue.[41] The placenta produces the potent vasodilator adrenomedullin: it is reduced in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.[42] Other vasodilators are also reduced, including prostacyclin, thromboxane A2, nitric oxide, and endothelins, also leading to vasoconstriction.[25]

Eclampsia is a form of hypertensive encephalopathy: cerebral vascular resistance is reduced, leading to increased blood flow to the brain, cerebral edema and resultant convulsions.[43] An eclamptic convulsion usually does not cause chronic brain damage unless intracranial haemorrhage occurs.[44]

Diagnosis

If a pregnant woman has already been diagnosed with pre-eclampsia during the current pregnancy and then develops a seizure, she may be assigned a 'clinical diagnosis' of eclampsia without further workup. While seizures are most common in the third trimester, they may occur any time from 20 weeks of pregnancy until 6 weeks after birth.[45] A diagnosis of eclampsia is most likely given the symptoms and medical history, and eclampsia can be assumed to be the correct diagnosis until proven otherwise.[46] However, if a woman has a seizure and it is unknown whether or not she has pre-eclampsia, testing can help make the diagnosis clear.

Vital signs

One of the core features of pre-eclampsia is high blood pressure. Blood pressure is a measurement of two numbers. If either the top number (systolic blood pressure) is greater than 140 mmHg or the bottom number (diastolic blood pressure) is greater than 90 mmHg, then the blood pressure is higher than the normal range and the person has high blood pressure. If the systolic blood pressure is greater than 160 or the diastolic pressure is greater than 110, the hypertension is considered to be severe.[15]

Laboratory testing

Another core feature of pre-eclampsia is proteinuria, which is the presence of excess protein in the urine. To determine if proteinuria is present, the urine can be collected and tested for protein; if there is 0.3 grams of protein or more in the urine of a pregnant woman collected over 24 hours, this is one of the diagnostic criteria for pre-eclampsia and raises the suspicion that a seizure is due to eclampsia.[15]

In cases of severe eclampsia or pre-eclampsia, the level of platelets in the blood can be low in a condition termed thrombocytopenia.[47][25] A complete blood count, or CBC, is a test of the blood that can be performed to check platelet levels.

Other investigations include: kidney function test, liver function tests (LFT), coagulation screen, 24-hour urine creatinine, and fetal/placental ultrasound.

Differential diagnosis

Convulsions during pregnancy that are unrelated to pre-eclampsia need to be distinguished from eclampsia. Such disorders include seizure disorders as well as brain tumor, aneurysm of the brain, and medication- or drug-related seizures. Usually, the presence of the signs of severe pre-eclampsia precede and accompany eclampsia, facilitating the diagnosis.

Prevention

Detection and management of pre-eclampsia is critical to reduce the risk of eclampsia. The USPSTF recommends regular checking of blood pressure through pregnancy in order to detect preeclampsia.[48] Appropriate management of women with pre-eclampsia generally involves the use of magnesium sulfate to prevent eclamptic seizures.[49] In some cases, low-dose aspirin has been shown to decrease the risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women, especially when taken in the late first trimester.[16]

Treatment

The four goals of the treatment of eclampsia are to stop and prevent further convulsions, to control the elevated blood pressure, to deliver the baby as promptly as possible, and to monitor closely for the onset of multi-organ failure.

Convulsions

Convulsions are prevented and treated using magnesium sulfate.[50] The study demonstrating the effectiveness of magnesium sulfate for the management of eclampsia was first published in 1955.[51] Effective anticonvulsant serum levels range from 2.5 to 7.5 mEq/liter. [52]

With intravenous administration, the onset of anticonvulsant action is fast and lasts about 30 minutes. Following intramuscular administration the onset of action is about one hour and lasts for three to four hours. Magnesium is excreted solely by the kidneys at a rate proportional to the plasma concentration and glomerular filtration. [52] Magnesium sulfate is associated with several minor side effects; serious side effects are uncommon, occurring at elevated magnesium serum concentrations > 7.0 mEQ/L. Serious toxicity can be counteracted with calcium gluconate. [53]

Even with therapeutic serum magnesium concentrations, recurrent convulsions may occur, and additional magnesium may be needed, but with close monitoring for respiratory, cardiac, and neurological depression. If magnesium administration with resultant high serum concentrations fail to control convulsions, the addition of other intravenous anticonvulsants may be used, facilitate intubation and mechanical ventilation, and to avoid magnesium toxicity including maternal thoracic muscle paralysis.

Magnesium sulfate results in better outcomes than diazepam, phenytoin or a combination of chlorpromazine, promethazine, and pethidine.[54][55][56]

Blood pressure management

Blood pressure control is used to prevent stroke, which accounts for 15 to 20 percent of deaths in women with eclampsia.[57] The agents of choice for blood pressure control during eclampsia are hydralazine or labetalol.[25] This is because of their effectiveness, lack of negative effects on the fetus, and mechanism of action. Blood pressure management is indicated with a diastolic blood pressure above 105–110 mm Hg.[28]

Delivery

If the baby has not yet been delivered, steps need to be taken to stabilize the woman and deliver her speedily. This needs to be done even if the baby is immature, as the eclamptic condition is unsafe for both baby and mother. As eclampsia is a manifestation of a type of non-infectious multiorgan dysfunction or failure, other organs (liver, kidney, lungs, cardiovascular system, and coagulation system) need to be assessed in preparation for a delivery (often a caesarean section), unless the woman is already in advanced labor. Regional anesthesia for caesarean section is contraindicated when a coagulopathy has developed.

There is limited to no evidence in favor of a particular delivery method for women with eclampsia. Therefore, the delivery method of choice is an individualized decision.[27]

Monitoring

Invasive hemodynamic monitoring may be elected in an eclamptic woman at risk for or with heart disease, kidney disease, refractory hypertension, pulmonary edema, or poor urine output.[25]

Etymology

The Greek noun ἐκλαμψία, eklampsía, denotes a "light burst"; metaphorically, in this context, "sudden occurrence." The New Latin term first appeared in Johannes Varandaeus’ 1620 treatise on gynaecology Tractatus de affectibus Renum et Vesicae.[58] The term toxemia of pregnancy is no longer recommended: placental toxins are not the cause of eclampsia occurrences, as previously believed.[59]

Popular culture

In Downton Abbey, a historical drama television series, the character Lady Sybil dies (in series 3, episode 5) of eclampsia shortly after child birth.[60]

In Call the Midwife, a medical drama television series set in London in the 1950s and 1960s, the character (in series 1, episode 4) named Margaret Jones is struck with pre-eclampsia, ultimately proceeding from a comatose condition to death. The term "toxemia" was also used for the condition, in the dialogue.[61]

In House M.D., a medical drama television series set in the U.S., Dr. Cuddy, the hospital director, adopts a baby whose teenage mother dies from eclampsia and had no other parental figures available.[61]

References

- "Chapter 40: Hypertensive Disorders". Williams Obstetrics (24th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. 2014. ISBN 9780071798938.

- WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia (PDF). 2011. ISBN 978-92-4-154833-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-13.

- Henderson, JT; Whitlock, EP; O'Connor, E; Senger, CA; Thompson, JH; Rowland, MG (20 May 2014). "Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (10): 695–703. doi:10.7326/M13-2844. PMID 24711050. S2CID 33835367.

- Smith, JM; Lowe, RF; Fullerton, J; Currie, SM; Harris, L; Felker-Kantor, E (5 February 2013). "An integrative review of the side effects related to the use of magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia management". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 13: 34. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-34. PMC 3570392. PMID 23383864.

- Abalos, E; Cuesta, C; Grosso, AL; Chou, D; Say, L (September 2013). "Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 170 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.005. PMID 23746796.

- Okoror, Collins E. M. (26 December 2018). "Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with eclampsia: a retrospective study at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital". International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (1): 108–114. doi:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20185404.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- Lambert, G; Brichant, JF; Hartstein, G; Bonhomme, V; Dewandre, PY (2014). "Preeclampsia: an update". Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica. 65 (4): 137–49. PMID 25622379.

- American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy (November 2013). "Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy" (PDF). Obstet. Gynecol. 122 (5): 1122–31. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. PMC 1126958. PMID 24150027.

- Okoror, Collins E. M. (26 December 2018). "Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with eclampsia: a retrospective study at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital". International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (1): 108–114. doi:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20185404.

- McDonald, SD; Lutsiv, O; Dzaja, N; Duley, L (August 2012). "A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes following magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in real-world use". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 118 (2): 90–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.01.028. PMID 22703834. S2CID 20361780.

- Arulkumaran, N.; Lightstone, L. (December 2013). "Severe pre-eclampsia and hypertensive crises". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 27 (6): 877–884. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.07.003. PMID 23962474.

- Okoror, Collins E. M. (26 December 2018). "Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with eclampsia: a retrospective study at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital". International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (1): 108. doi:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20185404.

- Emile R. Mohler (2006). Advanced Therapy in Hypertension and Vascular Disease. PMPH-USA. pp. 407–408. ISBN 9781550093186. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Stone, C. Keith; Humphries, Roger L. (2017). "Chapter 19: Seizures". Current diagnosis & treatment. Emergency medicine (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071840613. OCLC 959876721.

- Current diagnosis & treatment : obstetrics & gynecology. DeCherney, Alan H.,, McGraw-Hill Companies. (12th ed.). [New York]. 12 February 2019. ISBN 978-0071833905. OCLC 1080940730.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kane SC, Dennis A, da Silva Costa F, Kornman L, Brennecke S (2013). "Contemporary Clinical Management of the Cerebral Complications of Preeclampsia". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2013: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2013/985606. PMC 3893864. PMID 24489551.

- Gabbe MD, Steven G. (2017). "Chapter 31: Preeclampsia and Hypertensive Disorders". Obstetrics : Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Jennifer R. Niebyl MD, Joe Leigh Simpson MD, Mark B. Landon MD, Henry L. Galan MD, Eric R.M. Jauniaux MD, PhD, Deborah A. Driscoll MD, Vincenzo Berghella MD and William A. Grobman MD, MBA (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc. pp. 661–705. ISBN 9780323321082. OCLC 951627252.

- Okoror, Collins E. M. (26 December 2018). "Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with eclampsia: a retrospective study at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital". International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (1): 108–114. doi:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20185404.

- Cunningham, F. Gary (2014). "Chapter 40: Hypertensive Disorders". Williams Obstetrics. Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, Sheffield JS. (24th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9780071798938. OCLC 871619675.

- Fleisher MD, Lee A. (2018). "Chapter: Eclampsia". Essence of Anesthesia Practice. Roizen, Michael F.,, Roizen, Jeffrey D. (4th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier Inc. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9780323394970. OCLC 989062320.

- Bersten, Andrew D. (2014). "Chapter 63: Preeclampsia and eclampsia". Oh's Intensive Care Manual. Soni, Neil (Seventh ed.). [Oxford]: Elsevier Ltd. pp. 677–683. ISBN 9780702047626. OCLC 868019515.

- Okoror, Collins E. M. (26 December 2018). "Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with eclampsia: a retrospective study at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital". International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (1): 108–114. doi:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20185404.

- Robert Resnik, MD; Robert k. Creasy, MD; Jay d. Iams, MD; Charles j. Lockwood, MD; Thomas Moore, MD; Michael f Greene, MD (2014). "Chapter 46: Placenta Previa, Placenta Accreta, Abruptio Placentae, and Vasa Previa". Creasy and Resnik's maternal-fetal medicine : principles and practice. Creasy, Robert K.,, Resnik, Robert,, Greene, Michael F.,, Iams, Jay D.,, Lockwood, Charles J. (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA. pp. 732–742. ISBN 9781455711376. OCLC 859526325.

- Acog Committee On Obstetric Practice (January 2002). "ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002". Obstet Gynecol. 99 (1): 159–67. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. PMID 16175681.

- Gill, Prabhcharan; Tamirisa, Anita P.; Van Hook MD, James W. (2020), "Acute Eclampsia", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29083632, retrieved 2019-08-04

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice (April 2002). "ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 77 (1): 67–75. ISSN 0020-7292. PMID 12094777.

- Sibai, Baha M. (February 2005). "Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 105 (2): 402–410. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000152351.13671.99. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 15684172.

- "Chapter 35: Hypertension". High risk pregnancy : management options. James, D. K. (David K.), Steer, Philip J. (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier. 2011. pp. 599–626. ISBN 9781416059080. OCLC 727346377.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Cunningham FG, Fernandez CO, Hernandez C (April 1995). "Blindness associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 172 (4 Pt 1): 1291–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(95)91495-1. PMID 7726272.

- James, David K. (2011). "Chapter 48: Neurologic Complications of Preeclampsia/Eclampsia". High Risk Pregnancy. Steer, Philip J. (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 861–891. ISBN 9781416059080. OCLC 727346377.

- Cronenwett, Jack L. (2014). "Chapter 40: Systemic Complications: Respiratory". Rutherford's vascular surgery. Johnston, K. Wayne (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, Elsevier. pp. 626–637. ISBN 9781455753048. OCLC 877732063.

- Adams, James (2013). "Chapter 99: Seizures". Emergency medicine : clinical essentials (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/ Saunders. pp. 857–869. ISBN 9781437735482. OCLC 820203833.

- "Chapter 48: Pregnancy-Related Hypertension". Creasy and Resnik's Maternal-Fetal Medicine : Principles and Practice. Creasy, Robert K.,, Resnik, Robert,, Greene, Michael F.,, Iams, Jay D.,, Lockwood, Charles J. (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier Inc. 2014. pp. 756–781. ISBN 9781455711376. OCLC 859526325.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Gabbe MD, Steven G. (2017). "Chapter 31: Preeclampsia and Hypertensive Disorders". Obstetrics : Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Jennifer R. Niebyl MD, Joe Leigh Simpson MD, Mark B. Landon MD, Henry L. Galan MD, Eric R.M. Jauniaux MD, PhD, Deborah A. Driscoll MD, Vincenzo Berghella MD and William A. Grobman MD, MBA (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc. pp. 661–705.e3. ISBN 9780323321082. OCLC 951627252.

- Gardner, David G. (2018). "Chapter 16: The Endocrinology of Pregnancy". Greenspan's basic & clinical endocrinology. Shoback, Dolores M.,, Greenspan, Francis S. (Francis Sorrel), 1920-2016. (Tenth ed.). [New York]: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9781259589287. OCLC 995848612.

- Kasper, Dennis L. (2015). "Chapter 117: Gynecologic Malignancies". Harrison's principles of internal medicine. Fauci, Anthony S., 1940-, Hauser, Stephen L.,, Longo, Dan L. (Dan Louis), 1949-, Jameson, J. Larry,, Loscalzo, Joseph (19th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9780071802154. OCLC 893557976.

- Murray, Michael F. (2014). "Chapter 102: Pre-eclampsia". Clinical genomics : practical applications in adult patient care. Babyatsky, Mark W.,, Giovanni, Monica A.,, Alkuraya, Fowzan S.,, Stewart, Douglas R. (First ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9780071622448. OCLC 899740989.

- Williams obstetrics. Williams, J. Whitridge (John Whitridge), 1866-1931., Cunningham, F. Gary,, Leveno, Kenneth J.,, Bloom, Steven L.,, Spong, Catherine Y.,, Dashe, Jodi S. (25th ed.). New York. 12 April 2018. ISBN 978-1-259-64432-0. OCLC 958829269.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Roberts JM, Cooper DW (January 2001). "Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia". Lancet. 357 (9249): 53–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03577-7. PMID 11197372. S2CID 25280817.

- Greenspan's basic & clinical endocrinology. Gardner, David G.,, Shoback, Dolores M.,, Greenspan, Francis S., 1920- (Francis Sorrel) (10th ed.). New York, N.Y. 10 October 2017. ISBN 9781259589287. OCLC 1075522289.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Li H, Dakour J, Kaufman S, Guilbert LJ, Winkler-Lowen B, Morrish DW (November 2003). "Adrenomedullin is decreased in preeclampsia because of failed response to epidermal growth factor and impaired syncytialization". Hypertension. 42 (5): 895–900. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000095613.41961.6E. PMID 14517225.

- Cipolla MJ (July 2007). "Cerebrovascular function in pregnancy and eclampsia". Hypertension. 50 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.079442. PMID 17548723.

- Richards A, Graham D, Bullock R (March 1988). "Clinicopathological study of neurological complications due to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 51 (3): 416–21. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.3.416. PMC 1032870. PMID 3361333.

- Current medical diagnosis & treatment 2021. Papadakis, Maxine A.,, McPhee, Stephen J.,, Rabow, Michael W. (Sixtieth ed.). New York. 10 September 2020. ISBN 978-1-260-46986-8. OCLC 1191849672.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Edlow, Jonathan A.; Caplan, Louis R.; O'Brien, Karen; Tibbles, Carrie D. (February 2013). "Diagnosis of acute neurological emergencies in pregnant and post-partum women". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (2): 175–185. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70306-X. ISSN 1474-4465. PMID 23332362. S2CID 17711531.

- Tintinalli, Judith E. (2016). "Chapter 100: Maternal Emergencies After 20 Weeks of Pregnancy and in the Postpartum Period". Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine : A Comprehensive Study Guide. Stapczynski, J. Stephan,, Ma, O. John,, Yealy, Donald M.,, Meckler, Garth D.,, Cline, David, 1956- (Eighth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9780071794763. OCLC 915775025.

- Sperling, Jeffrey D.; Gossett, Dana R. (25 April 2017). "Screening for Preeclampsia and the USPSTF Recommendations". JAMA. 317 (16): 1629–1630. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.2018. PMID 28444259.

- Harrison's principles of internal medicine. Jameson, J. Larry,, Kasper, Dennis L.,, Longo, Dan L. (Dan Louis), 1949-, Fauci, Anthony S., 1940-, Hauser, Stephen L.,, Loscalzo, Joseph (20th ed.). New York. 13 August 2018. ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0. OCLC 1029074059.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Patel, Minal K.; Goodson, James L.; Alexander, James P.; Kretsinger, Katrina; Sodha, Samir V.; Steulet, Claudia; Gacic-Dobo, Marta; Rota, Paul A.; McFarland, Jeffrey; Menning, Lisa; Mulders, Mick N. (2020-11-13). "Progress Toward Regional Measles Elimination — Worldwide, 2000–2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (45): 1700–1705. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a6. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 7660667. PMID 33180759.

- Pritchard JA (February 1955). "The use of the magnesium ion in the management of eclamptogenic toxemias". Surg Gynecol Obstet. 100 (2): 131–40. PMID 13238166.

- "Magnesium Sulfate - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- Smith, Jeffrey Michael; Lowe, Richard F.; Fullerton, Judith; Currie, Sheena M.; Harris, Laura; Felker-Kantor, Erica (2013-02-05). "An integrative review of the side effects related to the use of magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia management". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 13 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-34. ISSN 1471-2393. PMC 3570392. PMID 23383864.

- Duley, L; Henderson-Smart, DJ; Walker, GJ; Chou, D (Dec 8, 2010). "Magnesium sulphate versus diazepam for eclampsia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD000127. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000127.pub2. PMC 7045443. PMID 21154341.

- Duley, L; Henderson-Smart, DJ; Chou, D (Oct 6, 2010). "Magnesium sulphate versus phenytoin for eclampsia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD000128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000128.pub2. PMID 20927719.

- Duley, L; Gülmezoglu, AM; Chou, D (Sep 8, 2010). "Magnesium sulphate versus lytic cocktail for eclampsia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD002960. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002960.pub2. PMC 7138041. PMID 20824833.

- Townsend, Rosemary; O’Brien, Patrick; Khalil, Asma (2016-07-27). "Current best practice in the management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy". Integrated Blood Pressure Control. 9: 79–94. doi:10.2147/IBPC.S77344. ISSN 1178-7104. PMC 4968992. PMID 27555797.

- Ong, S. (2003). "Pre-eclampsia: A historical perspective". In Baker, P.N.; Kingdom, J.C.P. (eds.). Pr-eclampsia: Current perspectives on management. Taylor & Francis. pp. 15–24. ISBN 978-1842141809.

- FAQ: Toxemia Archived 2015-09-25 at the Wayback Machine at the Pre-Eclampsia Foundation website

- Stone, Rachel Marie (January 30, 2013). "Stop With All the Dangerous Childbirth Stories Already". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- "Episode #1.4". 5 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2016 – via IMDb.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|