Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis, also known as intra-amniotic infection (IAI), is an inflammation of the fetal membranes (amnion and chorion) most commonly due to a bacterial infection.[1] Recently, experts have suggested using the term intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (Triple I) instead of the term chorioamnionitis, as a way to illustrate that chorioamnionitis can not be automatically confirmed if the mother simply only has a fever.[2] In addition, it is not automatically a reason to begin antibiotics.[2] Chorioamnionitis typically results from an infection caused by bacteria ascending from the vagina into the uterus but is also associated with premature or prolonged labor.[3] It triggers an inflammatory response to release various inflammatory signaling molecules that leads to increased prostaglandin and metalloprotease release. These substances promote uterine contractions and cervical ripening which causes premature birth.[4] The risk of developing chorioamnionitis increases with number of vaginal examinations performed in the final month of pregnancy, including during labor, as well as with tobacco and alcohol use.[5]

| Chorioamnionitis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrograph showing chorioamnionitis. The clusters of blue dots are inflammatory cells (neutrophils, eosinophils and lymphocytes). H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics and gynaecology |

Prevention of chorioamnionitis can occur by administering antibiotics if the amniotic sac bursts prematurely.[6] Chorioamnionitis can also be caught early by looking at signs and symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, or abnormal vaginal excretion.[7]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of clinical chorioamnionitis can include fever, leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/mm³), maternal (>100 bpm)[8] or fetal (>160 bpm) tachycardia, uterine tenderness and preterm rupture of membranes.[2]

Causes

Causes of chorioamnionitis have been found to stem from microorganism infection as well as obstetric and other related factors.[3][5]

Microorganisms

Bacterial, viral, and even fungal infections have been found to cause chorioamnionitis with the most common occurring from Ureaplasma, Fusobacterium, and Streptococcus bacteria species. Less commonly, Gardnerella, Mycoplasma, and Bacteroids bacterial species, as well as sexually transmitted infections of chlamydia and gonorrhea, have been implicated in the development of the condition as well.[5] Studies are continuing to identify other microorganism classes and species as infection sources.[9]

Obstetric and other

In addition to microorganism causes, birthing-related events, lifestyle, and ethnic background have been linked to an increase in the risk of developing chorioamnionitis.[9] Premature deliveries, ruptures of the membranes of the amniotic sac, prolonged labors, and first time giving birth have been associated with this condition.[10] At term women who experience a combination of pre-labor membrane ruptures and multiple invasive vaginal examinations, prolonged labors, or have meconium appear in the amniotic fluid are at higher risk than at term women experiencing just one of those events.[9] In other studies, smoking, alcohol use and drug use have been noted as risk factors in addition to an increased risk for those of African American ethnicity.[5][10]

Anatomy

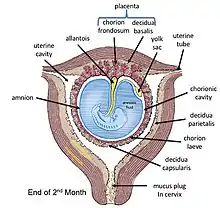

The amniotic sac consists of two parts:

- The outer membrane is the chorion. It is closest to the mother and physically supports the much thinner amnion.

- The chorion is the last and outermost of the membranes that make up the amniotic sac.[11]

- The inner membrane is the amnion. It is in direct contact with the amniotic fluid, which surrounds the fetus.

Diagnosis

Pathologic

Chorioamnionitis can be diagnosed from a histologic (tissue) examination of the fetal membranes.[10] Of note, confirmed histologic chorioamnionitis without any clinical symptoms is termed subclinical chorioamnionitis and is more common than symptomatic clinical chorioamnionitis.[2]

Infiltration of the chorionic plate by neutrophils is diagnostic of (mild) chorioamnionitis. More severe chorioamnionitis involves subamniotic tissue and may have fetal membrane necrosis and/or abscess formation.[1]

Severe chorioamnionitis may be accompanied by vasculitis of the umbilical blood vessels (due to the fetus' inflammatory cells) and, if very severe, funisitis (inflammation of the umbilical cord's connective tissue).[10]

Suspected clinical diagnosis

When intrapartum (meaning during delivery) fever is higher than 39.0 °C, a suspected diagnosis of chorioamnionitis can be made. Alternatively, if intrapartum fever is between 38.0 °C and 39.0 °C, an additional risk factor must be present to make a presumptive diagnosis of chorioamnionitis. Additional risk factors include:[12]

- Fetal tachycardia

- Maternal leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/mm³)[13]

- Purulent cervical drainage

Confirmed diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically not confirmed until after delivery. However, people with confirmed diagnosis and suspected diagnosis have the same post-delivery treatment regardless of diagnostic status. Diagnosis can be confirmed histologically or through amniotic fluid test results such as gram staining, glucose levels, or other culture results are consistent with infection.[12]

Prevention

If the amniotic sac breaks early into pregnancy, the potential of introducing bacteria in the amniotic fluid can increase, yet administering antibiotics maternally can potentially prevent chorioamnionitis and allow for a longer pregnancy.[6] In addition, it has been shown that it is not necessary to deliver the fetus quickly after chorioamnionitis is diagnosed, so a C-section is not necessary unless it is necessary for maternal reasons.[10] However, research has found that beginning labor early at approximately 34 weeks can lessen the likelihood of fetal death, and reduce the potential for excessive infection within the mother.[10]

In addition, providers should interview people suspected to have chorioamnionitis about whether they are experiencing signs and symptoms at scheduled obstetrics visits during pregnancy, including whether the individual has experienced excretion vaginally, whether the individual reports signs of being febrile, or if their abdominal area has been in pain.[7]

Treatment

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee Opinion proposes the use of antibiotic treatment in intrapartum mothers with suspected or confirmed chorioamnionitis and maternal fever without an identifiable cause.[12]

Intrapartum antibiotic treatment consists of:[14]

- Standard

- Ampicillin + gentamicin

- Alternative

- Ampicillin-Sulbactam

- Ticarcillin-Clavulanate

- Cefoxitine

- Cefotetan

- Piperacillin-Tazobactum

- Ertapenum

- Cesarean delivery

- Ampicillin and gentamicin plus either clindamycin or metronidazole

- Penicillin-allergy

- Vancomycin + gentamicin

- Gentamicin + clindamycin

However, there is not enough evidence to support the most efficient antimicrobial regimen,[15] starting the treatment during the intrapartum period is more effective than starting it postpartum; it shortens the hospital stay for the mother and the neonate.[16] There is currently not enough evidence to dictate how long antibiotic therapy should last. Completion of treatment/cure is only considered after delivery.[14]

Supportive measures

Acetaminophen is often used for treating fevers and may be beneficial for fetal tachycardia. There is possibly also an increased likelihood for neonatal encephalopathy when mothers have intrapartum fever.[10]

Outcomes

Chorioamnionitis has been found to have possible associations with numerous neonatal conditions. Among possible outcomes, intrapartum (during labor) chorioamnionitis may be associated with neonatal pneumonia, meningitis, sepsis, and death, as well as with long-term infant complications like bronchopulmonary dysplasia and cerebral palsy.[17] Furthermore, histological chorioamnionitis may increase the likelihood of newborn necrotizing enterocolitis, where one or more sections of the bowel die. This may occur because the fetal gut barrier becomes compromised and is more susceptible to conditions like infection and sepsis.[18] In addition to these possible associations, chorioamnionitis may act as a risk factor for premature birth and periventricular leukomalacia.[19]

Complications

For mother and fetus, chorioamnionitis may lead to further short and long-term issues when microbes move to different areas or trigger the inflammatory response.[10]

Maternal complications

- Higher risk for C-section

- Postpartum hemorrhage

- Endometritis[20]

- Bacteremia (often due to Group B streptococcus and Escherichia coli)[10]

- Pelvic abscess

Mothers with chorioamnionitis who undergo a C-section may be more likely to develop pelvic abscesses, septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, and infections at the surgical site.[9]

Fetal complications

Neonatal complications

- Perinatal death

- Asphyxia

- Early onset neonatal sepsis[21]

- Septic shock

- Neonatal pneumonia

In the long-term, infants may be more likely to experience cerebral palsy or neurodevelopmental disabilities, which seems to be related to the activation of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS) when the fetus is exposed to infected amniotic fluid or other foreign entities.[4][10] This systemic response results in neutrophil and cytokine release that can impair the fetal brain and other vital organs.[4][6] Compared to infants with clinical chorioamnionitis, it appears cerebral palsy may occur at a higher rate for those with histologic chorioamnionitis. However, more research needs to be done to examine this association.[22] There is also concern about the impact of FIRS on infant immunity as this is a critical time for growth and development. For instance, it may be linked to chronic inflammatory disorders, such as asthma.[23]

Epidemiology

Chorioamnionitis is approximated to occur in about 4%[7] of births in the United States. However, many other factors can increase the risk of chorioamnionitis. For example, in births with premature rupture of membranes (PROM), between 40 and 70% involve chorioamnionitis. Furthermore, clinical chorioamnionitis is implicated in 12% of all cesarean deliveries. Some studies have shown that the risk of chorioamnionitis is higher in those of African American ethnicity, those with immunosuppression, and those who smoke, use alcohol, or abuse drugs.[10]

Notes

- Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Chaiyasit N, Yoon BH, Kim YM (October 2015). "Acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis: definition, pathologic features, and clinical significance". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (4 Suppl): S29-52. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.040. PMC 4774647. PMID 26428501.

- Peng CC, Chang JH, Lin HY, Cheng PJ, Su BH (June 2018). "Intrauterine inflammation, infection, or both (Triple I): A new concept for chorioamnionitis". Pediatrics and Neonatology. 59 (3): 231–237. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2017.09.001. PMID 29066072.

- Cheng YW, Delaney SS, Hopkins LM, Caughey AB (November 2009). "The association between the length of first stage of labor, mode of delivery, and perinatal outcomes in women undergoing induction of labor". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 201 (5): 477.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.024. PMID 19608153.

- Galinsky R, Polglase GR, Hooper SB, Black MJ, Moss TJ (2013). "The consequences of chorioamnionitis: preterm birth and effects on development". Journal of Pregnancy. 2013: 412831. doi:10.1155/2013/412831. PMC 3606792. PMID 23533760.

- Sweeney EL, Dando SJ, Kallapur SG, Knox CL (January 2017). "The Human Ureaplasma Species as Causative Agents of Chorioamnionitis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 30 (1): 349–379. doi:10.1128/CMR.00091-16. PMC 5217797. PMID 27974410.

- Ericson JE, Laughon MM (March 2015). "Chorioamnionitis: implications for the neonate". Clinics in Perinatology. 42 (1): 155–65, ix. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2014.10.011. PMC 4331454. PMID 25678002.

- Fowler JR, Simon LV (October 2019). "Chorioamnionitis.". StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30335284.

- Sung JH, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Roh CR (June 2019). "Should the diagnostic criteria for suspected clinical chorioamnionitis be changed?". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 0: 1–10. doi:10.1080/14767058.2019.1618822. PMID 31084245.

- Czikk MJ, McCarthy FP, Murphy KE (September 2011). "Chorioamnionitis: from pathogenesis to treatment". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 17 (9): 1304–11. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03574.x. PMID 21672080.

- Tita AT, Andrews WW (June 2010). "Diagnosis and management of clinical chorioamnionitis". Clinics in Perinatology. 37 (2): 339–54. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2010.02.003. PMC 3008318. PMID 20569811.

- "28.2 Embryonic Development - Anatomy and Physiology | OpenStax". openstax.org. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- "Committee Opinion No. 712 Summary: Intrapartum Management of Intraamniotic Infection". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 130 (2): 490–492. August 2017. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002230. PMID 28742671.

- Zanella P, Bogana G, Ciullo R, Zambon A, Serena A, Albertin MA (June 2010). "[Chorioamnionitis in the delivery room]". Minerva Pediatrica. 62 (3 Suppl 1): 151–3. PMID 21090085.

- Tita AT. "Intraamniotic infection (clinical chorioamnionitis or triple I)". UpToDate. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Hopkins L, Smaill F (2002). "Antibiotic regimens for management of intraamniotic infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD003254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003254. PMC 6669261. PMID 12137684.

- Chapman E, Reveiz L, Illanes E, Bonfill Cosp X (December 2014). Reveiz L (ed.). "Antibiotic regimens for management of intra-amniotic infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD010976. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010976.pub2. PMID 25526426.

- "Intrapartum Management of Intraamniotic Infection". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- Been JV, Lievense S, Zimmermann LJ, Kramer BW, Wolfs TG (February 2013). "Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Pediatrics. 162 (2): 236–42.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.012. PMID 22920508.

- Wu YW, Colford JM (September 2000). "Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis". JAMA. 284 (11): 1417–24. doi:10.1001/jama.284.11.1417. PMID 10989405.

- Casey BM, Cox SM (March 1997). "Chorioamnionitis and endometritis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 11 (1): 203–22. doi:10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70349-4. PMID 9067792.

- Bersani I, Thomas W, Speer CP (April 2012). "Chorioamnionitis--the good or the evil for neonatal outcome?". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 25 (Suppl 1): 12–6. doi:10.3109/14767058.2012.663161. PMID 22309119. S2CID 11109172.

- Shi Z, Ma L, Luo K, Bajaj M, Chawla S, Natarajan G, et al. (June 2017). "Chorioamnionitis in the Development of Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review". Pediatrics. 139 (6): e20163781. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3781. PMC 5470507. PMID 28814548.

- Sabic D, Koenig JM (January 2020). "A perfect storm: fetal inflammation and the developing immune system". Pediatric Research. 87 (2): 319–326. doi:10.1038/s41390-019-0582-6. PMID 31537013. S2CID 202702137.

References

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Overview at Cleveland Clinic.

- Cerebral palsy inflammation link (29 November 2003) at BBC.