Dholavira

Dholavira (Gujarati: ધોળાવીરા) is an archaeological site at Khadirbet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch District, in the state of Gujarat in western India, which has taken its name from a modern-day village 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) south of it. This village is 165 km (103 mi) from Radhanpur. Also known locally as Kotada timba, the site contains ruins of an ancient Indus Valley Civilization/Harappan city.[1] Dholavira’s location is on the Tropic of Cancer. It is one of the five largest Harappan sites[2] and most prominent archaeological sites in India belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization.[3] It is also considered as having been the grandest of cities[4] of its time. It is located on Khadir bet island in the Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary in the Great Rann of Kutch. The 47 ha (120 acres) quadrangular city lay between two seasonal streams, the Mansar in the north and Manhar in the south.[5] The site was thought to be occupied from c.2650 BCE, declining slowly after about 2100 BCE, and to have been briefly abandoned then reoccupied until c.1450 BCE;[6] however, recent research suggests the beginning of occupation around 3500 BCE (pre-Harappan) and continuity until around 1800 BCE (early part of Late Harappan period).[7]

.jpg.webp) Part of the excavated site | |

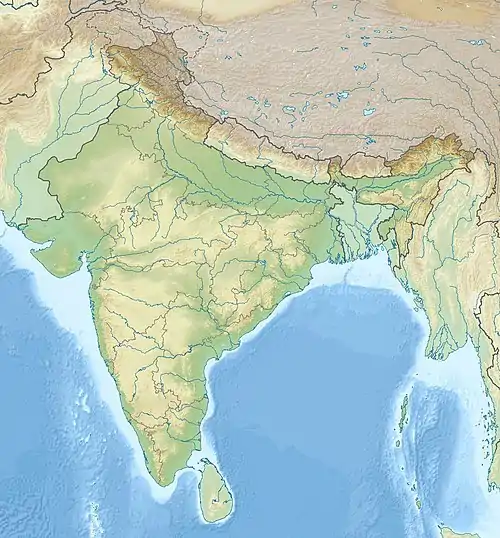

Shown within India  Dholavira (Gujarat) | |

| Location | Khadirbet, Kutch District, India |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 23°53′18.98″N 70°12′49.09″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 47 ha (120 acres) |

| History | |

| Periods | Harappa 1 to Harappa 5 |

| Cultures | Indus Valley Civilization |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Public access | Yes |

The site was discovered in 1967-68 by J. P. Joshi, of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and is the fifth largest of eight major Harappan sites. It has been under excavation since 1990 by the ASI, which opined that "Dholavira has indeed added new dimensions to personality of Indus Valley Civilisation."[8] The other major Harappan sites discovered so far are Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Ganeriwala, Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, Rupnagar and Lothal.

Chronology of Dholavira

Ravindra Singh Bisht, the director of the Dholavira excavations, has defined the following seven stages of occupation at the site:[9]

| STAGES | DATES | EVENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 2650–2550 BCE | Early Harappan – Mature Harappan Transition A |

| Stage II | 2550–2500 BCE | Early Harappan – Mature Harappan Transition B |

| Stage III | 2500–2200 BCE | Mature Harappan A |

| Stage IV | 2200–2000 BCE | Mature Harappan B |

| Stage V | 2000–1900 BCE | Mature Harappan C |

| 1900–1850 BCE | Period of desertion | |

| Stage VI | 1850–1750 BCE | Posturban Harappan A |

| 1750–1650 BCE | Period of desertion | |

| Stage VII | 1650–1450 BCE | Posturban Harappan B |

Recent C14 datings and stylistic comparisons with Amri II-B period pottery shows the first two phases should be termed Pre-Harappan Dholaviran Culture and re-dated as follows: Stage I (c. 3500-3200 BCE), and Stage II (c. 3200-2600 BCE).[10]

Excavations

Excavation was initiated in 1989 by the ASI under the direction of Bisht, and there were 13 field excavations between 1990 and 2005.[2] The excavation brought to light the urban planning and architecture, and unearthed large numbers of antiquities such as, animal bones, gold, silver, terracotta ornaments, pottery and bronze vessels. Archaeologists believe that Dholavira was an important centre of trade between settlements in south Gujarat, Sindh and Punjab and Western Asia.[11][12]

Architecture and material culture

Estimated to be older than the port-city of Lothal,[13] the city of Dholavira has a rectangular shape and organization, and is spread over 22 ha (54 acres). The area measures 771.1 m (2,530 ft) in length, and 616.85 m (2,023.8 ft) in width.[8] Unlike Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, the city was constructed to a pre-existing geometrical plan consisting of three divisions – the citadel, the middle town, and the lower town.[14] The acropolis and the middle town had been furnished with their own defence-work, gateways, built-up areas, street system, wells, and large open spaces. The acropolis is the most thoroughly fortified[8] and complex area in the city, of which it appropriates the major portion of the southwestern zone. The towering "castle" stands is defended by double ramparts.[15] Next to this stands a place called the 'bailey' where important officials lived.[16] The city within the general fortifications accounts for 48 ha (120 acres). There are extensive structure-bearing areas which are outside yet integral to the fortified settlement. Beyond the walls, another settlement has been found.[8] The most striking feature of the city is that all of its buildings, at least in their present state of preservation, are built of stone, whereas most other Harappan sites, including Harappa itself and Mohenjo-daro, are almost exclusively built of brick.[17] Dholavira is flanked by two storm water channels; the Mansar in the north, and the Manhar in the south. In the town square, there is a area high above the ground, called the "Citadel''.

Reservoirs

Bisht, who retired as the Joint Director-General of the ASI, said, "The kind of efficient system of Harappans of Dholavira, developed for conservation, harvesting and storage of water speaks eloquently about their advanced hydraulic engineering, given the state of technology in the third millennium BCE."[2] One of the unique features[18] of Dholavira is the sophisticated water conservation system[19] of channels and reservoirs, the earliest found anywhere in the world,[20] built completely of stone. The city had massive reservoirs, three of which are exposed.[21] They were used for storing fresh water brought by rains[19] or to store water diverted from two nearby rivulets.[22] This clearly came in response to the desert climate and conditions of Kutch, where several years may pass without rainfall. A seasonal stream which runs in a north-south direction near the site was dammed at several points to collect water. In 1998, another reservoir was discovered in the site.[23]

The inhabitants of Dholavira created sixteen or more reservoirs[6] of varying size during Stage III.[8] Some of these took advantage of the slope of the ground within the large settlement,[8] a drop of 13 metres (43 ft) from northeast to northwest. Other reservoirs were excavated, some into living rock. Recent work has revealed two large reservoirs, one to the east of the castle and one to its south, near the Annexe.[24]

The reservoirs are cut through stone vertically, and are about 7 m (23 ft) deep and 79 m (259 ft) long. They skirt the city, while the citadel and bath are centrally located on raised ground.[19] There is also a large well with a stone-cut trough connecting it to a drain meant for conducting water to a storage tank.[19] The bathing tank had steps descending inwards.[19]

In October 2014, excavation began on a rectangular stepwell which measured 73.4 m (241 ft) long, 29.3 m (96 ft) wide, and 10 m (33 ft) deep, making it three times bigger than the Great Bath of Mohenjedaro.[25]

Seal making

Some of the seals found at Dholavira, belonging to Stage III, contained animal only figures, without any type of script. It is suggested that these type of seals represent early conventions of Indus seal making.

Other structures and objects

A huge circular structure on the site is believed to be a grave or memorial,[19] although it contained no skeletons or other human remains. The structure consists of ten radial mud-brick walls built in the shape of a spoked wheel.[19] A soft sandstone sculpture of a male with phallus erectus but head and feet below ankle truncated was found in the passageway of the eastern gate.[19] Many funerary structures have been found (although all but one were devoid of skeletons),[19] as well as pottery pieces, terra cotta seals, bangles, rings, beads, and intaglio engravings.[19]

Hemispherical constructions

Seven hemispherical constructions were found at Dholavira, of which two were excavated in detail, which were constructed over large rock cut chambers.[8] Having a circular plan, these were big hemispherical elevated mud brick constructions. One of the excavated structures was designed in the form of a spoked wheel. The other was also designed in same fashion, but as a wheel without spokes. Although they contained burial goods of pottery, no skeletons were found except for one grave, where a skeleton and a copper mirror were found.[8] A necklace of steatite beads strung to a copper wire with hooks at both ends, a gold bangle, gold and other beads were also found in one of the hemispherical structures.[8]

These hemispherical structures bear similarity to early Buddhist stupas.[8] The Archaeological Survey of India, which conducted the excavation, opines that "the kind of design that is of spoked wheel and unspoked wheel also remind one of the Sararata-chakra-citi and sapradhi-rata-chakra-citi mentioned in the Satapatha Brahmana and Sulba-sutras".[8]

Findings

Painted Indus black-on-red-ware pottery, square stamp seals, seals without Indus script, a huge signboard measuring about 3 m (9.8 ft) in length, containing ten letters of Indus script. One poorly preserved seated male figure made of stone has also been found, comparable to high quality two stone sculptures found at Harappa.[26] Large black-slipped jars with pointed base were also found at this site. A giant bronze hammer, a big chisel, a bronze hand-held mirror, a gold wire, gold ear stud, gold globules with holes, copper celts and bangles, shell bangles, phallus-like symbols of stone, square seals with Indus inscription and signs, a circular seal, humped animals, pottery with painted motifs, goblets, dish-on-stand, perforated jars, Terracotta tumblers in good shape, architectural members made of ballast stones, grinding stones, mortars, etc., were also found at this site.[2] Stone weights of different measures were also found.[27]

Coastal route

It is suggested that a coastal route existed linking Lothal and Dholavira to Sutkagan Dor on the Makran coast.[28]

Language and script

The Harrapans spoke an unknown language and their script has not yet been deciphered. It is believed to have had about 400 basic signs, with many variations.[29] The signs may have stood both for words and for syllables.[29] The direction of the writing was generally from right to left.[30] Most of the inscriptions are found on seals (mostly made out of stone) and sealings (pieces of clay on which the seal was pressed down to leave its impression). Some inscriptions are also found on copper tablets, bronze implements, and small objects made of terracotta, stone and faience. The seals may have been used in trade and also for official administrative work.[31] A lot of inscribed material was found at Mohenjo-daro and other Indus Valley Civilisation sites.

Sign board

The most significant discoveries at Dholavira was made in one of the side rooms of the northern gateway of the city, and is generally known as the Dholavira Signboard. The Harappans had arranged and set pieces of the mineral gypsum to form ten large symbols or letters on a big wooden board.[32] At some point, the board fell flat on its face. The wood decayed, but the arrangement of the letters survived. The letters of the signboard are comparable to large bricks that were used in nearby walls. Each sign is about 37 cm (15 in) high and the board on which letters were inscribed was about 3 m (9.8 ft) long.[33] The inscription is one of the longest in the Indus script, with one symbol appearing four times, and this and its large size and public nature make it a key piece of evidence cited by scholars arguing that the Indus script represents full literacy. A four sign inscription with large letters on sandstone is also found at this site, considered first of such inscription on sandstone at any of Harappan sites.[2]

References

- "Ruins on the Tropic of Cancer".

- Subramanian, T. "The rise and fall of a Harappan city". The Archaeology News Network. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "Where does history begin?".

- Kenoyer & Heuston, Jonathan Mark & Kimberley (2005). The Ancient South Asian World. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780195222432.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Dholavira: A Harappan City - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 17. ISBN 9780759101722. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Sengupta, Torsa, et al. (2019)."Did the Harappan settlement of Dholavira (India) collapse during the onset of Meghalayan stage drought?" in Journal of Quaternary Science, First published: 26 December 2019.

- "Excavations-Dholavira". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Possehl, Gregory. (2004). The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective, New Delhi: Vistaar Publications, ISBN 81-7829-291-2, p.67.

- Sengupta, Torsa, et al. (2019)."Did the Harappan settlement of Dholavira (India) collapse during the onset of Meghalayan stage drought?"(Supplementary materials), in Journal of Quaternary Science, First published: 26 December 2019.

- [http://www.archaeology.org/0011/newsbriefs/aqua.html Aqua Dholavira - GUJARAT Magazine Archive]. Archaeology.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 177. ISBN 9781576079072. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Suman, Saket. "When history meets development". TheStatesman. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives (2008 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 174. ISBN 9781576079072. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 224. ISBN 9781576079072. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. 2008: ABC-CLIO. p. 226. ISBN 9781576079072. Retrieved 3 June 2016.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Wheeler, Mortimer (2 September 1968). The Indus Civilization: Supplementary Volume to the Cambridge History of India (1968 ed.). CUP Archive. p. 33. ISBN 9780521069588. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Education India. pp. 155 bottom. ISBN 978-813-17-1120-0.

- "Dholavira excavations throw light on Harappan civilisation". United News of India. Indian Express. 25 June 1997. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Dholavira: A Harappan City - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley : New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 84. ISBN 978-157-60-7907-2.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Education India. p. 155. ISBN 978-813-17-1120-0.

- "'Oldest dam' found". Rediff.com. 25 April 1998. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Possehl, Gregory. (2004). The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective, New Delhi: Vistaar Publications, ISBN 81-7829-291-2, p.69.

- "5,000-year-old Harappan stepwell found in Kutch, bigger than Mohenjodaro's". The Times of India Mobile Site. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus civilization : a contemporary perspective (2nd print ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780759101722.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 163. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 167. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Parpola, Asko (2005) Study of the Indus Script. 50th ICES Tokyo Session.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (4 February 2007). "Towards a scientific study of Indus Script". The Hindu. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. Indus Cities, Towns, and Villages. American Institute of Pakistan Studies, Islamabad. 1998

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Oxford University Press. 1998

- Possehl, Gregory. (2004). The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective, New Delhi: Vistaar Publications, ISBN 81-7829-291-2, p.70.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dholavira. |

- Excavations at Dholavira in Archaeological Survey of India website

- Dholavira Pictures by Archaeological Survey of India website

- Jurassic Park: Forest officials stumble upon priceless discovery near Dholavira; Express news service; 8 Jan 2007; Indian Express Newspaper

- ASI’s effort to put Dholavira on World Heritage map hits the roadblock; by Hitarth Pandya; 13 Feb 2009; Indian Express Newspaper

- ASI to take up excavation in Kutch's Khirasara; by Prashant Rupera, TNN; 2 November 2009; Times of India