Demographic history of Jerusalem

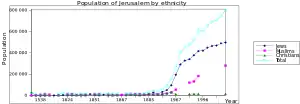

Jerusalem's population size and composition has shifted many times over its 5,000 year history. Since medieval times, the Old City of Jerusalem has been divided into Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Armenian quarters.

Most population data pre-1905 is based on estimates, often from foreign travellers or organisations, since previous census data usually covered wider areas such as the Jerusalem District.[1] These estimates suggest that since the end of the Crusades, Muslims formed the largest group in Jerusalem until the mid-19th century. Between 1838 and 1876, a number of estimates exist which conflict as to whether Jews or Muslims were the largest group during this period, and between 1882 and 1922 estimates conflict as to exactly when Jews became a majority of the population.

In 2016, the total population of Jerusalem was 882,700, including 536,600 Jews, 319,800 Muslims, 15,800 Christians, and 10,300 unclassified.[2] In 2003 the population of the Old City was 3,965 Jews and 31,405 "Arabs and others" (Choshen 12).

Overview

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

-Aerial-Temple_Mount-(south_exposure).jpg.webp) |

| Sieges |

| Places |

| Political status |

| Other topics |

Jerusalemites are of varied national, ethnic and religious denominations and include European, Asian and African Jews, Arabs of Sunni Shafi‘i Muslim, Melkite Orthodox, Melkite Catholic, Latin Catholic, and Protestant backgrounds, Armenians of the Armenian Orthodox and Armenian Catholic , Assyrians largely of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church, Maronites, and Copts.[3] Many of these groups were once immigrants or pilgrims that have over time become near-indigenous populations and claim the importance of Jerusalem to their faith as their reason for moving to and being in the city.[3]

Jerusalem's long history of conquests by competing and different powers has resulted in different groups living in the city many of whom have never fully identified or assimilated with a particular power, despite the length of their rule. Though they may have been citizens of that particular kingdom and empire and involved with civic activities and duties, these groups often saw themselves as distinct national groups (see Armenians, for example).[3] The Ottoman millet system, whereby minorities in the Ottoman Empire were given the authority to govern themselves within the framework of the broader system, allowed these groups to retain autonomy and remain separate from other religious and national groups. Some Palestinian residents of the city prefer to use the term Maqdisi or Qudsi as a Palestinian demonym.[4]

Historical population by religion

The tables below provide data on demographic change over time in Jerusalem, with an emphasis on the Jewish population. Readers should be aware that the boundaries of Jerusalem have changed many times over the years and that Jerusalem may also refer to a district or even a subdistrict under Ottoman, British, or Israeli administration, see e.g. Jerusalem District. Thus, year-to-year comparisons may not be valid due to the varying geographic areas covered by the population censuses.

Persian period

In the Achaemenid Yehud Medinata (Judah Province) the population of Jerusalem is estimated at between 1,500 and 2,750.[5]

1st century Judea

During the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), the population of Jerusalem was estimated at 600,000 persons by Roman historian Tacitus, while Josephus estimated that there were as many as 1,100,000 who were killed in the war.[6] Josephus also wrote that 97,000 Jews were sold as slaves. After the Roman victory over the Jews, as many as 115,880 dead bodies were carried out through one gate between the months of Nisan and Tammuz.[7]

Modern estimates of Jerusalem's population during the final Roman Siege of Jerusalem in 70 (CE) are variously 70,398 by Wilkinson in 1974,[8] 80,000 by Broshi in 1978,[9] and 60,000–70,000 by Levine in 2002.[10] According to Josephus, the populations of adult male scholarly sects were as follows: over 6,000 Pharisees, more than 4,000 Essenes and "a few" Sadducees.[11][12] New Testament scholar Cousland notes that "recent estimates of the population of Jerusalem suggest something in the neighbourhood of a hundred thousand".[13] A minimalist view is taken by Hillel Geva, who estimates from archaeological evidence that the population of Jerusalem before its 70 CE destruction was at most 20,000.[14]

Middle Ages

| Year | Jews | Muslims | Christians | Total | Original source | As quoted in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1130 | 0 | 0 | 30,000 | 30,000 | ? | Runciman |

| 1267 | 2* | ? | ? | ? | Nahmanides, Jewish scholar | |

| 1471 | 250* | ? | ? | ? | ? | Baron |

| 1488 | 76* | ? | ? | ? | ? | Baron |

| 1489 | 200* | ? | ? | ? | ? | Yaari, 1943[15] |

* Indicates families.

Early Ottoman era

| Year | Jews | Muslims | Christians | Total | Original source | As quoted in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1525–1526 | 1,194 | 3,704 | 714 | 5,612 | Ottoman taxation registers* | Cohen and Lewis[16] |

| 1538–1539 | 1,363 | 7,287 | 884 | 9,534 | Ottoman taxation registers* | Cohen and Lewis[16] |

| 1553–1554 | 1,958 | 12,154 | 1,956 | 16,068 | Ottoman taxation registers* | Cohen and Lewis[16] |

| 1596–77 | ? | 8,740 | 252 | ? | Ottoman taxation registers* | Cohen and Lewis[16] |

| 1723 | 2,000 | ? | ? | ? | Van Egmont & Heyman, Christian travellers | [17] |

Muslim "relative majority"

Henry Light, who visited Jerusalem in 1814, reported that Muslims comprised the largest portion of the 12,000 person population, but that Jews made the greatest single sect.[18] In 1818, Robert Richardson, family doctor to the Earl of Belmore, estimated the number of Jews to be 10,000, twice the number of Muslims.[19][20]

| Year | Jews | Muslims | Christians | Total | Original source | As quoted in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806 | 2,000 | 4,000 | 2,774 | 8,774 | Ulrich Jasper Seetzen, Frisian explorer[21] | Sharkansky, 1996[22][23] |

| 1815 | 4,000–5,000 | ? | ? | 26,000 | William Turner[24] | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1817 | 3,000–4,000 | 13,000 | 3,250 | 19,750 | Thomas R. Joliffe | [25] |

| 1821 | >4,000 | 8,000 | James Silk Buckingham | [26] | ||

| 1824 | 6,000 | 10,000 | 4,000 | 20,000 | Fisk and King, Writers | [27] |

| 1832 | 4,000 | 13,000 | 3,560 | 20,560 | Ferdinand de Géramb, French monk | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

Muslim or Jewish "relative majority"

Between 1838 and 1876, conflicting estimates exist regarding whether Muslims or Jews constituted a "relative majority" (or plurality) in the city.

Writing in 1841, the biblical scholar Edward Robinson noted the conflicting demographic estimates regarding Jerusalem during the period, stating in reference to an 1839 estimate attributed to the Moses Montefiore: "As to the Jews, the enumeration in question was made out by themselves, in the expectation of receiving a certain amount of alms for every name returned. It is therefore obvious that they here had as strong a motive to exaggerate their number, as they often have in other circumstances to underrate it. Besides, this number of 7000 rests merely on report; Sir Moses himself has published nothing on the subject; nor could his agent in London afford me any information so late as Nov. 1840."[28] In 1843, Reverend F.C. Ewald, a Christian traveler visiting Jerusalem, reported an influx of 150 Jews from Algiers. He wrote that there were now a large number of Jews from the coast of Africa who were forming a separate congregation.[29]

From the mid-1850s, following the Crimean War, the expansion of Jerusalem outside of the Old City began, with institutions including the Russian Compound, Kerem Avraham, the Schneller Orphanage, Bishop Gobat school and the Mishkenot Sha'ananim marking the beginning of permanent settlement outside the Jerusalem Old City walls.[30][31]

Between 1856 and 1880, Jewish immigration to Palestine more than doubled, with the majority settling in Jerusalem.[32] The majority of these immigrants were Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, who subsisted on Halukka.[32]

| Year | Jews | Muslims | Christians | Total | Original source | As quoted in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1838 | 3,000 | 4,500 | 3,500 | 11,500 | Edward Robinson | Edward Robinson, 1841[33] |

| 1844 | 7,120 | 5,000 | 3,390 | 15,510 | Ernst-Gustav Schultz, Prussian consul[34] | |

| 1846 | 7,515 | 6,100 | 3,558 | 17,173 | Titus Tobler, Swiss explorer[35] | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1847 | 10,000 | 25,000 | 10,000 | 45,000 | French consul estimates | Alexander Scholch, 1985[36] |

| 1849 | 895 | 3,074 | 1,872 | 5,841 | Official Ottoman census obtained by the Prussian consul Georg Rosen, showing male subjects | Alexander Scholch, 1985[37] |

| 1849 | 2,084 | ? | ? | ? | Moses Montefiore census, showing number of Jewish families[38] | |

| 1850 | 13,860 | ? | ? | ? | Dr. Ascher, Anglo-Jewish Association | |

| 1851 | 5,580 | 12,286 | 7,488 | 25,354 | Official census (only Ottoman citizens)[39] | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1853 | 8,000 | 4,000 | 3,490 | 15,490 | César Famin, French diplomat | Famin[40] |

| 1856 | 5,700 | 10,300 | 3,000 | 18,000 | Ludwig August von Frankl, Austrian writer | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1857 | 7,000 | ? | ? | 10–15,000 | HaMaggid periodical | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1862 | 8,000 | 6,000 | 3,800 | 17,800 | HaCarmel periodical | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1864 | 8,000 | 4,000 | 2,500 | 15,000 | British Embassy | Dore Gold, 2009[41] |

| 1866 | 8,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 16,000 | John Murray travel guidebook | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1867 | ? | ? | ? | 14,000 | Mark Twain, Innocents Abroad, Chapter 52 | [42] |

| 1867 | 4,000– 5,000 | 6,000 | ? | ? | Ellen-Clare Miller, Missionary | [43] |

| 1869 | 3,200* | n/a | n/a | n/a | Rabbi H. J. Sneersohn | New York Times[44] |

| 1869 | 9,000 | 5,000 | 4,000 | 18,000 | Hebrew Christian Mutual Aid Society | [45][46] |

| 1869 | 7,977 | 7,500 | 5,373 | 20,850 | Liévin de Hamme, Franciscan missionary | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1871–72 | 630* | 1,025* | 738* | 2,393* | Ottoman salname (official annals) for 1871–72 | Alexander Scholch, 1985[47] |

| 1871 | 4,000 | 13,000 | 7,000 | 20,560 | Karl Baedeker travel guidebook | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1874 | 10,000 | 5,000 | 5,500 | 20,500 | British consul in Jerusalem report to the House of Commons | Parliamentary Papers[48] |

| 1876 | 13,000 | 15,000 | 8,000 | 36,000 | Bernhard Neumann [49] | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

Jews as absolute or relative majority

Published in 1883, the PEF Survey of Palestine volume which covered the region noted that "The number of the Jews has of late increased at the rate of 1,000 to 1,500 per annum. Since 1875 the population of Jerusalem has rapidly increased. The number of Jews is now estimated at 15,000 to 20,000, and the population, including the inhabitants of the new suburbs, reaches a total of about 40,000 souls."[50]

In 1881–82, a group of Jews arrived from Yemen as a result of messianic fervor, in the phase known as the First Aliyah.[51][52] After living in the Old City for several years, they moved to the hills facing the City of David, where they lived in caves.[53] In 1884, the community, numbering 200, moved to new stone houses built for them by a Jewish charity.[54]

The Jewish population of Jerusalem, as for wider Palestine, increased further during the Third Aliyah of 1919–23 following the Balfour Declaration. Prior to this, a British survey in 1919 noted that most Jews in Jerusalem were largely Orthodox and that a minority were Zionists.[55]

| Year | Jews | Muslims | Christians | Total | Original source | As quoted in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1882 | 9,000 | 7,000 | 5,000 | 21,000 | Wilson | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1883 | 15,000–20,000 | ? | ? | 40,000 | PEF Survey of Palestine | PEF Survey of Palestine[50] |

| 1885 | 15,000 | 6,000 | 14,000 | 35,000 | Goldmann | Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001[23] |

| 1893 | >50% | ? | ? | ~40,000 | Albert Shaw, Writer | Shaw, 1894 [56] |

| 1896 | 28,112 | 8,560 | 8,748 | 45,420 | Calendar of Palestine for the year 5656 | Harrel and Stendel, 1974 |

| 1905 | 13,300 | 11,000 | 8,100 | 32,400 | 1905 Ottoman census (only Ottoman citizens) | U.O.Schmelz[57] |

| 1922 | 33,971 | 13,413 | 14,669 | 62,578 | Census of Palestine (British)[58] | Harrel and Stendel, 1974 |

| 1931 | 51,200 | 19,900 | 19,300 | 90,053 | Census of Palestine (British) | Harrel and Stendel, 1974 |

| 1944 | 97,000 | 30,600 | 29,400 | 157,000 | ? | Harrel and Stendel, 1974 |

| 1967 | 195,700 | 54,963 | 12,646 | 263,307 | Harrel, 1974 |

After Jerusalem Law

| Year | Jews | Muslims | Christians | Total | Proportion of Jewish residents | Original source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 292,300 | ? | ? | 407,100 | 71.8% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 1985 | 327,700 | ? | ? | 457,700 | 71.6% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 1987 | 340,000 | 121,000 | 14,000 | 475,000 | 71.6% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 1988 | 353,800 | 125,200 | 14,400 | 493,500 | 71.7% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 1990 | 378,200 | 131,800 | 14,400 | 524,400 | 72.1% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 1995 | 417,100 | 182,700 | 14,100 | 617,000 | 67.6% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 1996 | 421,200 | ? | ? | 602,100 | 70.0% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 2000 | 448,800 | ? | ? | 657,500 | 68.3% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 2004 | 464,500 | ? | ? | 693,200 | 67.0% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 2005 | 469,300 | ? | ? | 706,400 | 66.4% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 2007 | 489,480 | ? | ? | 746,300 | 65.6% | Jerusalem Municipality |

| 2011 | 497,000 | 281,000 | 14,000 | 801,000 | 62.0% | Israel Central Bureau of Statistics |

| 2015 | 524,700 | 307,300 | 12,400 | 857,800 | 61.2% | Israel Central Bureau of Statistics |

| 2016 | 536,600 | 319,800 | 15,800 | 882,700 | 60.8% | Israel Central Bureau of Statistics |

As of 24 May 2006, Jerusalem's population was 724,000 (about 10% of the total population of Israel), of which 65.0% were Jews (c. 40% of whom live in East Jerusalem), 32.0% Muslim (almost all of whom live in East Jerusalem) and 2% Christian. 35% of the city's population were children under age of 15. In 2005, the city had 18,600 newborns.[59]

These official Israeli statistics refer to the expanded Israel municipality of Jerusalem. This includes not only the area of the pre-1967 Israeli and Jordanian municipalities, but also outlying Palestinian villages and neighbourhoods east of the city, which were not part of Jordanian East Jerusalem prior to 1967. Demographic data from 1967 to 2012 showed continues growth of Arab population, both in relative and absolute numbers, and the declining of Jewish population share in the overall population of the city. In 1967, Jews were 73.4% of city population, while in 2010 the Jewish population shrank to 64%. In the same period the Arab population increased from 26,5% in 1967 to 36% in 2010.[60][61] In 1999, the Jewish total fertility rate was 3.8 children per woman, while the Palestinian rate was 4.4. This led to concerns that Arabs would eventually become a majority of the city's population.

Between 1999 and 2010, the demographic trends reversed themselves, with the Jewish fertility rate increasing and the Arab rate decreasing. In addition, the number of Jewish immigrants from abroad choosing to settle in Jerusalem steadily increased. By 2010, there was a higher Jewish than Arab growth rate. That year, the city's birth rate was placed at 4.2 children for Jewish mothers, compared with 3.9 children for Arab mothers. In addition, 2,250 Jewish immigrants from abroad settled in Jerusalem. The Jewish fertility rate is believed to be still currently increasing, while the Arab fertility rate remains on the decline.[62]

In 2016, Jerusalem had a population of 882,700, of which Jews comprised 536,600 (60.8%), Muslims 319,800 (36.2%), Christians 15,800 (1.8%), and 10,300 unclassified (1.2%).[2]

Demographic key dates

- 4500–3500 BCE: First settlement established near Gihon Spring (earliest archeological evidence)

- c. 1550–1400 BCE: Jerusalem becomes a vassal to the New Kingdom of Egypt

- c. 1000 BCE: According to the Bible, King David conquers Jerusalem and makes it the capital of the Kingdom of Israel (2 Samuel 5:6–7:6). His son King Solomon builds the First Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount.

- 732 BCE: Jerusalem becomes a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire[63]

- 587–586 BCE: Conquest of Jerusalem by Babylonians; Nebuchadnezzar II fought Pharaoh Apries's attempt to invade Judah. Jerusalem mostly destroyed including the First Temple, and the city's prominent citizens deported to Babylon (Biblical sources only)

- 539 BCE: Cyrus the Great conquers Babylon, allowing Babylonian Jews to return from the Babylonian captivity to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple (Biblical sources only, see Cyrus (Bible) and the Return to Zion)

- 530 BCE: The Second Jewish Temple was rebuilt, on the same Temple Mount as the first Jewish Temple.

- 350 BCE: Jerusalem revolts against Artaxerxes III, who retakes the city and burns it down in the process. Jews who supported the revolt are sent to Hyrcania on the Caspian Sea.

- 332–200 BCE: Jerusalem capitulates to Alexander the Great, and is later incorporated into the Ptolemaic Kingdom (301BCE) and Seleucid Empire (200BCE).

- 175 BCE: Antiochus IV Epiphanes accelerates Seleucid efforts to eradicate the Jewish religion, outlaws Sabbath and circumcision, sacks Jerusalem and erects an altar to Zeus in the Second Temple after plundering it.

- 164 BCE: The Hasmoneans take control of part of Jerusalem, whilst the Seleucids retain control of the Acra (fortress) in the city and most surrounding areas.

- 63 BCE: Roman Empire under Pompey takes city

- 70 CE: Titus ends the major portion of First Jewish–Roman War and destroys Herod's Temple. The Sanhedrin is relocated to Yavne, and the city's leading Christians relocate to Pella

- 136: Hadrian formally reestablishes the city as Aelia Capitolina, and forbids Jewish and Christian presence in the city. Restrictions over Christian presence in the city are relaxed two years later.

- 324–325: Emperor Constantine holds the First Council of Nicaea and confirms status of Jerusalem as a Christian patriarchate.[64] A significant wave of Christian immigration to the city begins. The ban on Jews entering the city remains in force, but they are allowed to enter once a year to pray at the Western Wall on Tisha B'Av

- c. 380: Tyrannius Rufinus and Melania the Elder found the first monastery in Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives

- 614: Jerusalem falls to Jewish and Persian forces, specifically Khosrow II's Sasanian Empire until it is retaken in 629. This was a result of the Jewish revolt against Heraclius, a Jewish insurrection against the Byzantine Empire across the Levant.[65] The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is burned and much of the Christian population is massacred.[66][67]

- 636–637: Caliph Umar conquers Jerusalem. According to Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, Patriarch Sophronius and Umar are reported to have agreed the Pact of Umar, which guaranteed Christians freedom of religion but prohibited Jews from living in the city. The Armenian Apostolic Church began appointing its own bishop in Jerusalem in 638. A surviving Jewish chronicle from the Cairo Geniza however states that Umar permitted seventy Jewish families to settle in the city.[68] The Jews requested to settle in the southern part of the city near the Temple Mount which was granted, evidence of this location of the Jewish quarter is provided in a Geniza letter dated 1064. Later Jewish texts from tenth and eleventh century also indicate the "King of Ishmael" allowing them to settle in the city.[69]

- 797: Abbasid–Carolingian alliance – the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was restored and the Latin hospital was enlarged, encouraging Christian travel to the city.[70]

- 1009–1030: Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim orders destruction of churches and synagogues in the empire, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Caliph Ali az-Zahir authorizes them rebuilt 20 years later.

- 1077: Jerusalem revolts against the rule of Emir Atsiz ibd Uvaq who retakes the city and massacres the local population.[71]

- 1099: First Crusaders capture Jerusalem and slaughter most of the city's Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. The Dome of the Rock is converted into a church.

- 1187: Saladin captures Jerusalem from Crusaders and allows Jewish and Orthodox Christian settlement. The Dome of the Rock is converted to an Islamic center of worship again.

- 1229: A 10-year treaty is signed allowing Christians freedom to live in the unfortified city. The Ayyubids retained control of the Muslim holy places.

- 1244: Mercenary army of Khwarazmians destroyed the city.

- 1260: Jerusalem raided by the Mongols under Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa. Hulagu Khan sends a message to Louis IX of France that Jerusalem remitted to the Christians under the Franco-Mongol alliance

- 1267: Nahmanides goes to Jerusalem and prays at the Western Wall. Reported to have found only two Jewish families in the city

- 1482: The visiting Dominican priest Felix Fabri described Jerusalem as "a collection of all manner of abominations". As "abominations" he listed Saracens, Greeks, Syrians, Jacobites, Abyssianians, Nestorians, Armenians, Gregorians, Maronites, Turcomans, Bedouins, Assassins, a sect possibly Druzes, Mamelukes, and "the most accursed of all", Jews. Only the Latin Christians "long with all their hearts for Christian princes to come and subject all the country to the authority of the Church of Rome".

- 1517: The Ottoman Empire captures Jerusalem under Sultan Selim I who proclaims himself Caliph of the Islamic world

- 1604: First Protectorate of missions agreed, in which the Christian subjects of Henry IV of France were free to visit the Holy Places of Jerusalem. French missionaries begin to travel to Jerusalem.

- 1700: Judah the Pious and 1,000 followers settle in Jerusalem.

- 1774: The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca is signed giving Russia the right to protect all Christians in Jerusalem.

- 1821: Greek War of Independence – Jerusalem's Christian population (the majority being Greek Orthodox), were forced by the Ottoman authorities to relinquish their weapons, wear black and help improve the city's fortifications

- 1837: Galilee earthquake of 1837 results in Jews from Safed and Tiberias resettling in Jerusalem.

- 1839–1840: Rabbi Judah Alkalai publishes "The Pleasant Paths" and "The Peace of Jerusalem", urging the return of European Jews to Jerusalem and Palestine.

- 1853–1854: A treaty is signed confirming France and the Roman Catholic Church as the supreme authority in the Holy Land with control over the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, contravening the 1774 treaty with Russia and triggering the Crimean War.

- 1860: The first Jewish neighborhood (Mishkenot Sha'ananim) outside the Old City walls is built, in an area later known as Yemin Moshe, by Moses Montefiore and Judah Touro.[72][73]

- 1862: Moses Hess publishes Rome and Jerusalem, arguing for a Jewish homeland in Palestine centered on Jerusalem

- 1873–1875: Mea Shearim is built.

- 1882: The First Aliyah results in 35,000 Jewish immigrants entering the Palestine region

- 1901: Ottoman restrictions on Jewish immigration to and land acquisition in Jerusalem district take effect

- 1901–1914: The Second Aliyah results in 40,000 Jewish immigrants entering the Palestine region

- 1917: The Ottomans are defeated at the Battle of Jerusalem during the World War I and the British Army takes control. The Balfour Declaration had been issued a month before.

- 1919–1923: The Third Aliyah results in 35,000 Jewish immigrants entering the Mandatory Palestine region

- 1924–1928: The Fourth Aliyah results in 82,000 Jewish immigrants entering the Mandatory Palestine region

- 1929–1939: The Fifth Aliyah results in 250,000 Jewish immigrants entering the Mandatory Palestine region

- 1947–1949: Palestine war led to displacement of Palestinian Arab and Jewish populations in the city and its division. All Jewish residents of the eastern part of the city were expelled by Arab forces and the entire Jewish Quarter was destroyed.[74] Palestinian Arab villages such as Lifta, al-Maliha, Ayn Karim and Deir Yassin were depopulated.

- 1967: The Six-Day War results in East Jerusalem being captured by Israel and few weeks later expansion of the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality to East Jerusalem and some surrounding area. The Old City is captured by the IDF and the Moroccan Quarter, comprising 135 houses and the 12th-century Afdaliya or Sheikh Eid Mosque, is demolished, creating a plaza in front of the Western Wall. Israel declares Jerusalem unified and announces free access to holy sites of all religions.

See also

References

- Usiel Oskar Schmelz, in Ottoman Palestine, 1800–1914: Studies in Economic and Social History, Gad G. Gilbar, Brill Archive, 1990

- "Table III/9 - Population in Israel and in Jerusalem, by Religion, 1988 - 2016" (PDF). www.jerusaleminstitute.org.il. 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-10. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- Final draft

- Hecht, Richard (2000). To Rule Jerusalem. p. 189.

- The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Ancient Israel

- Josephus (The Wars Of The Jews Book VI Ch 9 Sec 3)

- "Jerusalem". JewishEncyclopedia.com. 1903-11-15. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Wilkinson, "Ancient Jerusalem, Its Water Supply and Population", PEFQS 106, pp. 33–51 (1974).

- Estimating the Population of Ancient Jerusalem, Magen Broshi, BAR 4:02, Jun 1978

- "According to Levine, because the new area encompassed by the Third Wall was not densely populated, assuming that it contained half the population of the rest of the city, there were between 60,000 and 70,000 people living in Jerusalem.", Rocca, "Herod's Judaea: A Mediterranean State in the Classical World", p. 333 (2008). Mohr Siebeck.

- Stern, Sacha (2011-04-21). Sects and Sectarianism in Jewish History. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004206489.

- Antiquities of the Jews, 17.42

- Cousland, "The Crowds in the Gospel of Matthew", p. 60 (2002). Brill.

- Hillel Geva (2013). "Jerusalem's Population in Antiquity: A Minimalist View". Tel Aviv. 41 (2): 131–160.

- Avraham Yaari, Igrot Eretz Yisrael, p. 98.(Tel Aviv, 1943)

- Amnon Cohen and Bernard Lewis (1978). Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century. Princeton University Press. pp. 14–15, 94. ISBN 0-691-09375-X. The registers give counts of tax-paying households, bachelors, religious men, and disabled men. We followed Cohen and Lewis on taking 6 as the average household size, even though they call it "conjectural" and note that other scholars have suggested averages between 5 and 7.

- Archived May 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Light, Henry (1818). Travels in Egypt, Nubia, Holy Land, Mount Libanon and Cyprus, in the year 1814. Rodwell and Martin. p. 178.

The population is said to be twelve thousand, of which the largest proportion is Mussulmen: the greatest of one sect are Jews: the rest are composed of Christians of the East, belonging either to the Armenian, Greek, Latin, or Coptish sects.

- Richardson, Robert (1822). Travels Along the Mediterranean and Parts Adjacent: In Company with the Earl of Belmore, During the Years 1816-17-18: Extending as Far as the Second Cataract of the Nile, Jerusalem, Damascus, Balbec, &c. ... T. Cadell. pp. 256–.

- John Griffith Mansford (M.R.C.S.) (1829). A Scripture Gazetteer; or, geographical and historical dictionary of places and people, mentioned in the Bible. p. 244.

- Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (2007-09-27). "A Brief Account of the Countries Adjoining the Lake of Tiberias, the Jordan ..." Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Sharkansky, Ira (1996). Governing Jerusalem: Again on the world's agenda. Wayne State University Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-8143-2592-0.

- Kark, Ruth; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and its environs: quarters, neighborhoods, villages, 1800-1948. Wayne State University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-8143-2909-8.

- Turner, William (1820). Journal of a Tour in the Levant. John Murray. pp. 264–.

- Joliffe, Thomas R. (1822). Letters from Palestine: Description of a Tour Through Galilee and Judea. To which are Added Letters from Egypt.

- Buckingham, James Silk (1821). Travels in Palestine through the countries of Bashan and Gilead, east of the River Jordan, including a visit to the cities of Geraza and Gamala in the Decapolis. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown.

During our stay here, I made the most accurate estimate that my means of information admitted, of the actual population of Jerusalem at the present moment. From this it appeared that the fixed residents, more than one half of whom are Mohammedans, are about eight thousand; but the continual arrival and departure of strangers, make the total number of those present in the city from ten to fifteen thousand generally, according to the season of the year. The proportion which the numbers of those of different sects bear to each other in this estimate, was not so easily ascertained. The answers which I received to enquiries on this point, were framed differently by the professors of every different faith. Each of these seemed anxious to magnify the number of those who believed his own dogmas, and to diminish that of the professors of other creeds. Their accounts were therefore so discordant, that no reliance could be placed on the accuracy of any of them. The Mohammedans are certainly the most numerous, and these consist of nearly equal portions of Osmanli Turks, from Asia Minor; descendents of pure Turks by blood, but Arabians by birth; a mixture of Turkish and Arab blood, by intermarriages; and pure Syrian Arabs, of an unmixed race. Of Europeans, there are only the few monks of the Catholic convent, and the still fewer Latin pilgrims who occasionally visit them. The Greeks are the most numerous of ail the Christians, and these are chiefly the clergy and devotees. The Armenians follow next in order, as to numbers, but their body is thought to exceed that of the Greeks in influence and in wealth. The inferior sects of Copts, Abyssinians, Syrians, Nestorians, Maronites, Chaldeans, &c. are scarcely perceptible in the crowd. And even the Jews are more remarkable from the striking peculiarity of their features and dress, than from their numbers, as contrasted with the other bodies.

- Fisk and King, 'Description of Jerusalem,' in The Christian Magazine, July 1824, page 220. Mendon Association, 1824. (The figures are preceded by the comment "the following estimate seems to us as probably correct as any one we have heard". The authors also note that, "some think the Jews more numerous than the Mussulmans.")

- Edward Robinson (1841). "Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal ..." Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Jerusalem Illustrated History Altas, Martin Gilbert, Jerusalem 1830–1850, p.37

- Sephardi entrepreneurs in Jerusalem: the Valero family 1800–1948 By Joseph B. Glass, Ruth Kark. p.174

- Kark, Ruth; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800–1948. Wayne State University Press. pp. 74, table on p.82–86. ISBN 0-8143-2909-8.

The beginning of construction outside the Jerusalem Old City in the mid-19th century was linked to the changing relations between the Ottoman government and the European powers. After the Crimean War, various rights and privileges were extended to non-Muslims who now enjoyed greater tolerance and more security of life and property. All of this directly influenced the expansion of Jerusalem beyond the city walls. From the mid-1850s to the early 1860s, several new buildings rose outside the walls, among them the mission house of the English consul, James Finn, in what came to be known as Abraham’s Vineyard (Kerem Avraham), the Protestant school built by Bishop Samuel Gobat on Mount Zion; the Russian Compound; the Mishkenot Sha’ananim houses: and the Schneller Orphanage complex. These complexes were all built by foreigners, with funds from abroad, as semi-autonomous compounds encompassed by walls and with gates that were closed at night. Their appearance was European, and they stood out against the Middle-Eastern-style buildings of Palestine.

- S. Zalman Abramov (1918-05-13). Perpetual Dilemma: Jewish Religion in the Jewish State. ISBN 9780838616871. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Edward Robinson, Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: a journal of travels in the year 1838, Volume 2, 1841, page 85

- "Jerusalem, eine Vorlesung". Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Titus Tobler (1867). Bibliographica geographica Palaestinae: Zunächst kritische uebersicht gedruckter und ungedruckter beschreibungen der reisen ins Heilige Land. S. Hirzel.

- Scholch 1985, p. 492.

- Scholch 1985, p. 491.

- "Montefiore Families". Montefiorecensuses.org. Archived from the original on 2015-11-07. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Wolff, Press, "The Jewish Yishuv", pp 427-433, as quotes in Kark and Oren-Nordheim

- "Histoire de la rivalité et du protectorat des églises chrétiennes en Orient". Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Gold, Dore (2009). The Fight For Jerusalem. Regnery publishing. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-59698-102-7.

- Mark Twain, Chapter 52, Innocents Abroad

- Ellen Clare Miller, Eastern Sketches – notes of scenery, schools and tent life in Syria and Palestine. Edinburgh: William Oliphant and Company. 1871. Page 126: 'It is difficult to obtain a correct estimate of the number of inhabitants of Jerusalem...'

- The New York Times, February 19, 1869 ; See also I. Harold Scharfman, The First Rabbi, Pangloss Press, 1988, page 524 which reports the figure as 3,100.

- Burns, Jabez. Help-Book for Travelers to The East. 1870. Page 75

- Hebrew Christian Mutual Aid Society. Almanack of 1869

- Scholch 1985, p. 486, Table 1.

- Parliamentary Papers, House of Commons and Command (1874), page 992

- Die heilige Stadt und deren Bewohner in ihren naturhistorischen, culturgeschichtlichen, socialen und medicinischen Verhältnissen. Published by Der Verfasser, page 216; 512 pages

- Survey of Western Palestine, Volume III: Judea, page 163

- Tudor Parfitt (1997). The road to redemption: the Jews of the Yemen, 1900–1950. Brill's series in Jewish Studies, vol 17. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 53.

- Nini, Yehuda (1991). The Jews of the Yemen, 1800–1914. Taylor & Francis. pp. 205–207. ISBN 978-3-7186-5041-5.

- Wisemon, Tamar (2008-02-28). "Streetwise: Yemenite steps". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Man, Nadav (9 January 2010). "Behind the lens of Hannah and Efraim Degani – part 7". Ynet.

- Rhett, Maryanne A. (19 November 2015). The Global History of the Balfour Declaration: Declared Nation. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-31276-5.

- Review Of Reviews. Volume IX. Jan–Jun, 1894. Albert Shaw, Editor. Page 98. "The present population of Jerusalem is not far from forty thousand, and more than half are Jews."

- Gād G. Gîlbar (1990). Ottoman Palestine, 1800-1914: Studies in Economic and Social History. Brill Archive. p. 35. ISBN 90-04-07785-5.

- "1922 Palestine Census". Archive.org. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Jerusalem Day" (PDF). Cbs.gov.il. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- "Jerusalem : Facts and Trends 2012" (PDF). Jiis.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- "Is Jerusalem Being "Judaized"? | Jerusalem Center For Public Affairs". Jcpa.org. 2003-03-01. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- "Press release : Population : End of 2011 (provisional data)" (PDF). Jiis.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- "Kingdoms of the Levant - Israelites". Historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Schaff's Seven Ecumenical Councils: First Nicaea: Canon VII: "Since custom and ancient tradition have prevailed that the Bishop of Aelia [i.e., Jerusalem] should be honored, let him, saving its due dignity to the Metropolis, have the next place of honor."; "It is very hard to determine just what was the “precedence” granted to the Bishop of Aelia, nor is it clear which is the "metropolis" referred to in the last clause. Most writers, including Hefele, Balsamon, Aristenus and Beveridge consider it to be Cæsarea; while Zonaras thinks Jerusalem to be intended, a view recently adopted and defended by Fuchs; others again suppose it is Antioch that is referred to."

- Sharkansky, Ira (1996). Governing Jerusalem: Again on the World's Agenda. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 63.

- Hussey, J.M. 1961. The Byzantine World. New York, New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, p. 25.

- Karen Armstrong. 1997. Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. New York, New York: Ballantine Books, p. 229. ISBN 0-345-39168-3

- Joshua Prawer, Haggai Ben-Shammai (1996). The History of Jerusalem: The Early Muslim Period (638–1099). NYU Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-8147-6639-2.

- Pamela Berger (2012). The Crescent on the Temple: The Dome of the Rock as Image of the Ancient Jewish Sanctuary. Brill Publishers. pp. 45, 46. ISBN 978-9004203006.

- Heck, Gene W. (2006). Charlemagne, Muhammad, and the Arab roots of capitalism. p. 172. ISBN 9783110192292.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. 2007. Historic Cities of the Islamic World

- "Mishkenot Sha'ananim". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Archived December 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "S/8439* of 6 March 1968". Unispal.un.org. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

Bibliography

- Jewish National Council (1947). "First Memorandum: historical survey of the waves of the number and density of the population of ancient Palestine; Presented to the United Nations in 1947 by Vaad Leumi on Behalf of the Creation of a Jewish State" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-08.

- Jewish National Council (1947). "Second Memorandum: historical survey of the Jewish population in Palestine from the fall of the Jewish state to the beginning of zionist pioneering; Presented to the United Nations in 1947 by Vaad Leumi on Behalf of the Creation of a Jewish State" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-08.

- Jewish National Council (1947). "Third Memorandum: historical survey of the waves of Jewish immigration into Palestine from the arab conquest to the first zionist pioneers; Presented to the United Nations in 1947 by Vaad Leumi on Behalf of the Creation of a Jewish State" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08.

- Salo Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, Columbia University Press, 1983.

- Maya Choshen, ed. (2004). "Table III/14 – Population of Jerusalem, by Age, Quarter, Sub-Quarter, and Statistical Area, 2003" (PDF). Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2006.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics information page

- Jerusalem: Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Population (1910–2000) at israelipalestinianprocon.org

- Bruce Masters, Christians And Jews In The Ottoman Arab World, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Population of Jerusalem until 1945 (Table 10) at mideastweb.org

- United Nations (1983). "International Conference on the Question of Palestine—The Status of Jerusalem". United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved February 26, 2006.

- Time Magazine (April 16, 2001). "Jerusalem". Retrieved March 25, 2006.

- Runciman, Steven (1980). The First Crusade. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-23255-4.

- Martin Gilbert (1987). "Jerusalem Illustrated History Atlas". p. 35. Archived from the original on 2010-07-29. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (2002). "Jerusalem: Special Bulletin" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2006. Retrieved February 27, 2006.

- United Nations (1997). "The Status of Jerusalem". UNISPAL. Division for Palestinian Rights. Prepared for, and under the guidance of, the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People. Archived from the original on November 25, 2001. Retrieved February 26, 2006.

- Mark Twain (1867). "Innocents Abroad". Retrieved Feb 9, 2014.

- Scholch, Alexander (1985). "The Demographic Development of Palestine". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 17 (4): 485–505. doi:10.1017/s0020743800029445. JSTOR 163415.