Cyclone Ron

Severe Tropical Cyclone Ron was the strongest tropical cyclone on record to impact Tonga. The system was first noted as a tropical depression, to the northeast of Samoa on January 1, 1998. Over the next day the system gradually developed further and was named Ron as it developed into a Category 1 tropical cyclone on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale during the next day. The system subsequently continued to move south-westwards and became a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone, as it passed near Swains Island during January 3.

| Category 5 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 5 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

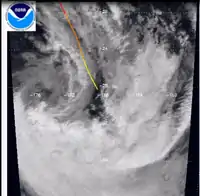

Cyclone Ron at peak intensity after recurving towards Tonga on January 5 | |

| Formed | January 1, 1998 |

| Dissipated | January 9, 1998 Absorbed by Cyclone Susan |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 230 km/h (145 mph) 1-minute sustained: 270 km/h (165 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 900 hPa (mbar); 26.58 inHg |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | $566,000 (1998 USD) |

| Areas affected | Samoan Islands, Tonga, Wallis and Futuna |

| Part of the 1997–98 South Pacific cyclone season | |

intensification proceeded at a fairly rapid rate. Ron reached the peak intensity of 145 mph (225 km/h) on January 5, becoming one of the most intense cyclones in the Southern hemisphere in that decade, when Ron was at north-northwest of Apia, Samoa, three days after initial development. The cyclone maintained this strength for about 36 hours, while re-curving to the south-southeast. Then, Ron started weakening while passing between central Tonga and Niue on January 7. Finally, by January 9, Ron was absorbed by the much larger circulation of Severe Tropical Cyclone Susan.

Meteorological history

During January 1, 1998 the Fiji Meteorological Service (FMS) reported that a tropical depression had developed about 835 km (520 mi) to the northeast of the Samoan Islands.[1] The system subsequently moved south-westwards under the influence of an area of high pressure and gradually developed further as its organisation and outflow improved.[2][3] During the next day the FMS reported that the system had developed into a Category 1 Tropical Cyclone, on the Australian Tropical Cyclone Intensity Scale and named it Ron.[1] At around the same time the Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center initiated advisories on the system, and designated it as Tropical Cyclone 10P with 1-minute wind speeds of 65 km/h (40 mph).[3] During that day the system continued to move south-westwards and gradually organized further and became a Category 3 Severe Tropical Cyclone during January 3, as it passed about 20 km (10 mi) to the north of Swains Island.[1][4][5]

After passing to the north of Swains Island, Ron continued to intensify and developed an eye as it moved south-westwards, before RSMC Nadi reported that it had become a Category 5 Severe Tropical Cyclone at 00:00 UTC on January 5.[4][6] RSMC Nadi subsequently reported six hours later that the system had peaked with estimated 10-minute sustained wind-speeds of 145 mph (225 km/h) and an estimated minimum pressure of 900 hPa (26.58 inHg).[1][4] At this time the system was located to the northeast of Wallis Island and was thought to be the strongest tropical cyclone in the South Pacific Basin since Severe Tropical Cyclone Hina of the 1984-85 season.[7] The NPMOC subsequently reported that the system had peaked as a category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 165 mph (270 km/h) and an estimated minimum pressure of 892 hPa (26.34 inHg).[8][9]

As the system peaked in intensity during January 5, the system recurved towards the southeast and passed about 55 km (35 mi) to the east of Wallis Island.[4] During the next day Ron remained at it peak intensity before it passed, about 30 km (20 mi) to the east of the Tongan island of Niuafo'ou.[1][4] During January 7, the system started to weaken as it accelerated southeastwards, and passed in between the main Tongan islands and Niue.[7] The system subsequently moved below 25S and left the tropics during the next day, before Ron was last noted being absorbed by Severe Tropical Cyclone Susan during January 9. After absorbing Ron, Susan transitioned into an extra-tropical cyclone, before it was last noted during January 10, bringing an unseasonable cold snap to New Zealand.[10][1][11]

Preparations and impact

Severe Tropical Cyclone Ron caused no deaths and various levels of damage, as it affected Swains Island, Wallis and Futuna and Tonga, while the name Ron was retired from the Lists of tropical cyclone names for the region due to the impact of this system.[1][12] Between January 2–3, Swains Island became the first island to be affected by Ron, with severe impacts to structures reported on the island from winds of up to 145 km/h (90 mph).[1][13] There were no deaths or damages reported on the island, after the 49 residents took shelter in a concrete structure.[14][15]

The system subsequently became the fourth and final tropical cyclone to affect the French territory of Wallis and Futuna during 1997 and 1998, after cyclones Gavin, Hina and Keli had affected the islands.[16][17] Ahead of the system affecting the islands between January 4–6, residents were put on maximum alert for the system by the local disaster management centre.[17][18][19] As a result, residents were urged to stock up with food and water, while a crisis centre was set up in the capital Mata-Utu and Air Calédonie cancelled flights to the islands.[20][21] On the island of Wallis winds of up to 130 km/h (80 mph), and a rainfall total of 109 mm (4.3 in) were recorded in the Hihifo District on January 6.[17] Widespread damage to roofs, trees, coastal roads, fales and food crops were recorded while water, electricity supplies and communication network were also disrupted.[17][19][21] Residents of the island of Futuna evacuated inland and sought higher ground as tidal waves of between 7–9 metres (23–30 ft) affected the island.[19][21][22]

Tonga

After affecting both Wallis and Futuna and Swains Island, the system became the strongest tropical cyclone on record in Tonga, as it passed near Niuafo'ou at peak intensity.[1][23] The system was the third tropical cyclone to affect the island nation in 10 months, after Cyclone's Hina and Keli affected the islands during March and June 1997.[24] Ahead of the system affecting the islands tropical cyclone alerts and warnings were issued for the whole nation by the Tonga Meteorological Department.[25] The worst affected Tongan island was Niuafo'ou where considerable damage occurred, while some damage was reported on other islands including Niuatoputapu, Tafahi, and Vava'u.[1]

On the island of Niuafo'ou sustained winds of 110 km/h (70 mph) were reported, while it was estimated that winds on the island had peaked at between 125–145 km/h (80–90 mph).[7] During the system's aftermath, a survey team was sent to Niuafoou, Niuatoputapu and Tafahi to assess the damage and the impact of the cyclone on the inhabitants.[26] According to the report made by them, the cyclone left 99 families without home and 43 ones in need of tarpaulins to repair damages, most of them in the Niuafo'ou island.[26] Also, Ron's winds caused extensive damage to agriculture and vegetation of the islands, in which includes total loss of fruit and breadfruit trees and severe damage to cassava and banana crops.[26]

Aftermath and records

Ron's destructive winds caused severe damage in Tonga's sanitation systems, increasing the danger of an outbreak of infectious diseases. Approximately 30% of the water tanks and 95% of the catchment covers had been damaged, leading to a water shortage.[27] Also, according to Tonga's National Disaster Relief Committee, the great loss of plantations and vegetation led to a six-month food shortage.[28] Replanting programmes took up to 6–8 months to restore all the lost vegetation.[27]

Several governments and organizations assisted the people affected by Ron. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs as allocated an Emergency Cash Grant of US$20,000 of relief items and coverage of transportation costs. The Government of New Zealand has provided temporary shelters and assistance with repairs to Government and public health buildings, as well as assistance with replanting with a total value of NZ$36,500 (approximately US$21,340). The United Kingdom provided supplies for the repair of water and sanitary systems of a total value of approximately £15,000 (US$25,000).[26] The South Pacific Forum Secretariat in Fiji also helped Tonga, releasing US$10,000 from a special disaster fund.[29]

References

- RSMC Nadi — Tropical Cyclone Centre (August 29, 2007). RSMC Nadi Tropical Cyclone Seasonal Summary 1997-98 (PDF) (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Naval Pacific Meteorological and Oceanographic Center (January 1, 1998). "Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert January 1, 1998 21z". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on August 3, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- Naval Pacific Meteorological and Oceanographic Center (January 2, 1998). "Tropical Cyclone 10P (Ron) Warning 1 January 2, 1998 00z". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on July 31, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- RSMC Nadi — Tropical Cyclone Centre (May 22, 2009). "Best Track Data for the 1997–98 season". Fiji Meteorological Service. United States: International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Naval Pacific Meteorological and Oceanographic Center (January 3, 1998). "Tropical Cyclone 10P (Ron) Warning 4 January 3, 1998 15z". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on August 3, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- Naval Pacific Meteorological and Oceanographic Center (January 4, 1998). "Tropical Cyclone 10P (Ron) Warning 5 January 4, 1998 15z". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on August 3, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- Chappel Lori-Carmen; Bate, Peter W (June 2, 2000). "The South Pacific and Southeast Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclone Season 1997–98" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Bureau of Meteorology. 49: 121–138. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1999). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1998 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. pp. 127–138. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center. "Tropical Cyclone 10P (Ron) best track analysis". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- MetService (May 22, 2009). "TCWC Wellington Best Track Data 1967–2006". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship.

- "Blame Cyclone Susan for cold snap". The Southland Times. New Zealand: The Southland Times Co. Ltd. January 10, 1998. p. 1. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (October 8, 2020). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2020 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. I-4–II-9 (9–21). Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Tropical Storm Ron ravish Swains Islands" (PDF). Solomon Star. January 9, 1998. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- Hopkins, Edward; DataStreme Ocean Central Staff (January 16, 2012). "WEEKLY OCEAN NEWS; 2-6 January 2012". pp. 1–11, 21. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- "Pacific ENSO Update — Special Bulletin" (Newsletter issued 4th Quarter 1997, Vol.3, No.4). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 26, 1998. pp. 1–11, 21. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- Kersemakers, Mark; RSMC Nadi — Tropical Cyclone Centre (April 4, 1998). Tropical Cyclone Gavin: March 2 — 11, 1997 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report 96/7). Fiji Meteorological Service. pp. 1–11, 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- "Wallis and Futuna Cyclone Passes De 1880 à nos jours". Meteo France New Caledonia. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- "Cyclone Ron causes widespread damage, heads for Noumea". AAP Newsfeed. January 6, 1998. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Pacific Islands Report (January 7, 1998). "Three Cyclones threaten Pacific; Wallis and Futuna hit". Pacific Islands Development Program/Center for Pacific Islands Studies. Archived from the original on August 3, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- "Pacific islands brace for cyclone". Agence France Presse. January 4, 1998. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Cyclone Ron Whips Up 9-Metre Tidal Waves". AAP Newsfeed. January 6, 1998. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Cyclone Ron hits islands". The Daily Telegraph. January 7, 1998. p. 25. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Meteorology Division of the Ministry of Environment, Energy, Climate Change, Disaster Management, Meteorology, Information and Communications (August 8, 2014). "El Nino Advisory No.1 for Tonga — An El Niño Watch is now in force for Tonga" (PDF) (Press release). Government of Tonga. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- A report on the list of the tropical cyclones that has affected at least a part of Tonga from 1960 to Present (PDF) (Report). Tonga Meteorological Service. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- "Cyclone Ron smashes Niuafo'ou lesser damage reported from Niuatoputapu". Island Snapshot. January 8, 1998. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- Tonga Cyclone Ron Situation Report No. 1. ReliefWeb (Report). United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs. January 27, 1998. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- Meteorology Division of the Ministry of Environment, Energy, Climate Change, Disaster Management, Meteorology, Information and Communications (August 8, 2014). "El Nino Advisory No.1 for Tonga — An El Niño Watch is now in force for Tonga" (PDF) (Press release). Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Government of Tonga. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1998). "Tonga says two islands in dire needs of food relief". Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1998). "South Pacific forum releases funds for Fiji cyclone recovery". Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

External links

- World Meteorological Organization

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- New Zealand MetService

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center