Cyclone Friedhelm

Cyclone Friedhelm,[1] also referred to unofficially as Hurricane Bawbag,[nb 1] was an intense extratropical cyclone which brought hurricane-force winds to Scotland at the beginning of December 2011. The storm also brought prolonged gales and rough seas to the rest of the British Isles, as well as parts of Scandinavia. On 8 December, winds reached up to 165 mph (266 km/h) at elevated areas, with sustained wind speeds of up to 80 mph (130 km/h) reported across populous areas. The winds uprooted trees and resulted in the closure of many roads, bridges, schools and businesses. Overall, the storm was the worst to affect Scotland in 10 years,[2] though a stronger storm occurred less than a month afterwards, on 3 January 2012.[3] Although the follow-up storm was more intense, the winter of 2011–12 is usually remembered for Bawbag (an insult meaning "scrotum") among Scots.

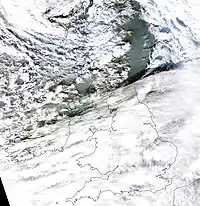

Friedhelm crossing the British Isles on 8 December 2011 | |

| Type | European windstorm, extratropical cyclone |

|---|---|

| Formed | 7 December 2011 |

| Dissipated | 13 December 2011 |

| Lowest pressure | 956 mb (28.2 inHg) |

| Highest winds |

|

| Highest gust | 265 km/h (165 mph) Cairngorm Summit |

| Casualties | 1 |

| Areas affected | British Isles, Scandinavia |

Naming

The Free University of Berlin names low-pressure systems affecting Europe and gave the name Friedhelm to this storm.[1] In Scotland, the storm was dubbed Hurricane Bawbag, the term bawbag being a Scots slang word for "scrotum", which is also used as an insult or as a jocular term of endearment.[4][5][6]

The name sparked a trending topic on Twitter, which became one of the top trending hashtags worldwide.[7][8] Stirling Council also used the Twitter tag.[9] Rob Gibson, the Convener of the Scottish Parliamentary Environment Committee, was the first politician to use the term on national television.

Meteorological history

At 00:00 UTC on 8 December 2011, the Met Office noted a strong mid-latitude cyclone along the polar front to the west of Scotland. The polar front supported multiple cold fronts moving southeastward through the Atlantic toward mainland Europe, as well as an eastward-moving warm front approaching Great Britain. In conjunction with strong high pressure to the south, an extremely tight pressure gradient developed along the deep low and produced a large area of high winds.[10]

Because of the high temperature gradient between the warm and cold air masses, the cyclone underwent a phase of explosive deepening.[11] By 08:00 UTC, the low had attained a minimum barometric pressure of 977 hPa (28.9 inHg), bringing gale-force winds to much of western Great Britain.[12] The minimum pressure further dipped to 957 hPa (28.3 inHg) around 12:00 UTC, with maximum sustained winds of at least 105 mph (169 km/h) observed at the surface.[13][14] An overall pressure drop of 44 hPa (1.3 inHg) was observed over just 24 hours, which combined with the extreme winds earned it the label "weather bomb" by meteorologists.[11] A FAAM research aircraft had intercepted the storm on several occasions as part of the DIAMET[15] research project, providing valuable data on its wind profile, temperature and humidity.[16]

By 9 December, the low had crossed Great Britain and moved into the North Sea toward western Scandinavia. The weakening occluded portion of the low—located along its centre—produced south-southeasterly gale-force winds across the peninsula. Further north, a large area of heavy snowfall and rough winds developed, while the heaviest rains occurred to the south of the centre.[17] It passed through Sweden with hurricane-force gusts,[18] though its winds and rainfall weakened significantly as it moved over Finland on 10 December.[19]

Preparations and warnings

On 7 December, the Met Office issued a red weather warning—its highest warning—for the Central Belt of Scotland.[20] This was the first time the Met Office had ever issued a red alert for wind for the United Kingdom.[21] They informed the public to take action and urged them to listen to police warnings.[20]

By 08:00 UTC on 8 December, all schools in the west of Scotland had been closed, while remaining schools in the east were told to close at lunchtime but there were a lot of schools in West Lothian which decided to stay open all day, following advice from the Scottish Government.[22] In addition, many tertiary centres of education, such as Edinburgh University, Glasgow University who were taking exams on that day, Glasgow Caledonian University and University of the West of Scotland halted their operations as a safety precaution. Also closed were public museums, galleries, sports centres, and many council buildings and libraries.[23] The Police in Scotland advised the public not to travel, and the Tay, Forth, Skye and Erskine bridges were closed to all traffic.[23] Officials feared widespread structural damage to roofs and weak buildings, resulting in the closure of several tourist attractions in central Scotland, including Edinburgh Castle and Princes Street Gardens.[24]

Effects

The storm brought gales to much of the British Isles and large parts of the Scandinavian Peninsula, causing widespread power outages and traffic disruptions. The highest winds occurred in Scotland, where hurricane-force winds battered coastal structures and uprooted trees. Additionally, heavy rainfall flooded some locations in England, Wales and Sweden. Despite the severity of its winds, the storm left no deaths in its wake.

The storm was classified Hurricane-force 12 on the Beaufort scale.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calm | Light Air | Light Breeze | Gentle Breeze | Moderate Breeze | Fresh Breeze | Strong Breeze | Near Gale | Gale | Strong Gale | Storm | Violent Storm | Hurricane Force |

| Light Winds | High Winds | Gale-force | Storm-force | Hurricane-force | ||||||||

| <1 mph <1 knot <0.3 m/s <2 km/h |

1–3 mph 1–3 knots 0.3–1.5 m/s 2–5 km/h |

4–7 mph 4–6 knots 1.6–3.3 m/s 6–11 km/h |

8–12 mph 7–10 knots 3.4–5.5 m/s 12–19 km/h |

13–18 mph 11–16 knots 5.5–7.9 m/s 20–28 km/h |

18–24 mph 17–21 knots 8.0–10.7 m/s 29–38 km/h |

25–31 mph 22–27 knots 10.8–13.8 m/s 39–49 km/h |

31–38 mph 28–33 knots 13.9–17.1 m/s 50–61 km/h |

39–46 mph 34–40 knots 17.2–20.7 m/s 62–74 km/h |

47–54 mph 41–47 knots 20.8–24.4 m/s 75–88 km/h |

55–63 mph 48–55 knots 24.5–28.4 m/s 89–102 km/h |

64–72 mph 56–63 knots 28.5–32.6 m/s 103–117 km/h |

≥73 mph ≥63 knots ≥32.7 m/s ≥118 km/h |

Scotland

The cyclone brought hurricane-force winds to large portions of Scotland through much of 8 December. The summit of Cairn Gorm recorded a gust speed of 165 mph (266 km/h), though sustained winds at the surface averaged 105 mph (169 km/h) and 80 mph (130 km/h) in populous areas.[25][26] The high winds generated large waves along coastlines and blew trees and debris into power lines. About 150,000 Scottish households lost power, 70,000 of which still had not had their electricity returned by nightfall.[27] Two hospitals, The Belford and Victoria Hospital, suffered power and telephone service cuts.[28]

The storm disrupted many of Scotland's public transport services, ScotRail operated a reduced timetable across all parts of the country as a result, and routes from Edinburgh to Aberdeen, Perth and Dundee were suspended. Sixty-four passengers on a train running on the West Highland Line were stranded, near Crianlarich, after the line was forced to close[29] In some areas buses ran in place of trains due to line problems.[30] Glasgow Airport cancelled 37 flights, and Edinburgh Airport 21 flights.[31] Ferry services in the Western Isles were also affected, with the majority being cancelled.[29] Bus operators in the Central Belt withdrew double-decker buses from operation after the Scottish Government advised all high sided vehicles not to travel and a number of buses were blown over.[32]

In the North Sea, the Petrojarl Banff, a floating production storage and offloading vessel carrying 4,400 tonnes (4,900 short tons) of oil, and the Apollo Spirit, which has 96,300 tonnes (106,200 short tons) on board, lost tension in some of their anchors as they were battered by the hurricane-force winds. The Apollo Spirit lost tension in one of its eight anchors, while five of the ten anchors supporting the Banff went slack.

Strathclyde Police reported that they received calls for 500 weather-related incidents during the course of the day.[29] In Campbeltown, Falkirk and Stirling a number of streets were closed after slates and chimneys fell from roofs.[24] High winds toppled a school bus travelling along the A737 near Dalry, North Ayrshire.[33] A wind turbine near Ardrossan burst into flames in the high winds.[34] Additionally, many Christmas lights in Aberdeen were blown down.[35] In Glasgow, the winds caused the River Clyde to burst its banks and overflow.[36]

Ireland

The low produced near hurricane-force gusts across the island of Ireland, with the highest winds reported along Northern Ireland coastal areas. The worst of the storm occurred in County Donegal, where gusts neared 140 km/h (87 mph). In Dublin, the winds uprooted trees, knocked over bins and blew debris through streets.[37] Some homes lost power during the storm, but the cuts did not cause significant disruption. Rivers rose in the winds and many burst their banks, causing light flooding across minor roads. A few buildings sustained minor wind damage to their roofs.[38] A bridge connecting the Fanad Peninsula to Carrigart was closed to vehicles.[37] Rail and ferry operators suspended their services, leaving passengers stranded.[38]

England and Wales

The storm had a significant impact on parts of the North of England.[39] There was flooding in Cumbria near Windermere, which left some cars adrift in water. High winds prompted the cancellation of train services as far south as Newcastle.[40] In North Yorkshire heavy rain and snow melt combined to cause widespread flooding in Swaledale leading to closure of several roads and the partial collapse of the bridge over the River Swale at Grinton.[41] A search and rescue helicopter from RAF Kinloss was scrambled to rescue those caught in the flooding.[41]

Storm conditions and heavy rain hit Wales, while hurricane-force winds were confined to the northern regions. Aberdaron, on the tip of the Llŷn Peninsula, recorded a gust of 81 mph (130 km/h), which was the highest for the country. In Swansea, winds of up to 70 mph (110 km/h) were reported. Flood alerts were also issued for several rivers in Wales due to the high rainfall.[42]

Scandinavia

The Swedish Meteorological Institute issued a class two warning.[43] In Gothenburg, roads and some cellars were submerged, and the Älvsborg Bridge and Götatunneln were closed due to high winds.[44][45] The winds damaged structures and left over 14,000 customers without power.[46]

Aftermath

Over 70,000 Scottish customers remained without electricity on 9 December, and by 10 December that number had dropped to 2,000.[47] Several schools were shut for a second day, including all schools in Orkney, Caithness and the north coast of Sutherland in the Highlands, while some schools were closed in Aberdeenshire, Angus, Argyll and Bute, Shetland, Stirling and the Western Isles.[48]

In popular culture

"Hurricane Bawbag" provides the background and part of the plot mechanism for Irvine Welsh's novel A Decent Ride (2015).

Notes

- The official name for this storm, designated by the Free University of Berlin, is Cyclone Friedhelm; however, the most common name given to the storm, particularly by media in the United Kingdom, was Hurricane Bawbag. The storm was not, however, an actual hurricane; rather, it was a powerful European windstorm with hurricane-force winds.

References

- "Low Pressure Systems 2011". Institute of Meteorology, Free University of Berlin. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Cook, James (8 December 2011). "Scotland battered by worst storm for 10 years". BBC News. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "A major winter storm brought very strong winds across much of the UK on 3 January 2012". Met Office. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "How internet sensation Hurricane Bawbag helped Scotland conquer the world". Daily Record. Scotland. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- STEPHEN MCGINTY (9 December 2011). "Would Bawbag's proud progenitor please stand up and take a bow – Cartoon". The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Scots slang highlighted after country is battered by Hurricane Bawbag". Daily Record. 10 December 2011. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Scotland's Hurricane Bawbag raises Twitter storm – the top reactions". STV News. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Phillip Schofield left bemused by Hurricane Bawbag". STV News. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Hurricane Bawbag is a Twitter hit worldwide for Scotland". The Drum. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Surface pressure forecast: Met Office view of 0000 UTC surface analysis (Report). Exeter, United Kingdom: Met Office. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Edwards, Tim (9 December 2011). "Scotland storm: what is a weather bomb?". The Week. London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- High seas forecast and storm warnings: The general synopsis at 08:00 UTC Thu 08 Dec (Report). Exeter, United Kingdom: Met Office. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Windstorm Friedhelm (Report). Risk Management Solutions Inc. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- UK weather forecast: New area of high winds and blizzards affecting northern Scotland (Report). Exeter, United Kingdom: Met Office. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- Centre for Atmospheric Science. "DIAMET Project". The University of Manchester. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Research into the violent Atlantic storm". Exeter, United Kingdom: Met Office. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- (in Swedish) Oväder gav översvämningar i Västsverige och snökaos i norr (Report). Norrköping, Sweden: Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "More power outages and traffic problems in the storm". Stockholm News. 10 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- (in Swedish) Knutsson, Lars (10 December 2011). Väderöversikt 10 December 2011 kl 12:45 (Report). Norrköping, Sweden: Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Red alert as weather warning issued for Lothians". The Scotsman. 7 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Leader: Fuss about the weather blows over". The Scotsman. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Scottish Government asks schools to close for severe gales". The Courier. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- PA (8 December 2011). "Stormy winds disrupt schools and transport". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "BBC News – Report: Scotland's winter winds". BBC. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "BBC News – Scotland storm blackout hitting thousands". BBC. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Video: Scotland hammered by severe wind storm". 3 News. Auckland, New Zealand: MediaWorks New Zealand. Associated Press. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Scotland storm: Work to restore power to homes". BBC News. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Anderson, Andrew (8 December 2011). "Scotland storm blackout hitting thousands". BBC News. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "The Big Storm: Winds reach 165mph, schools shut and transport in chaos as Scotland takes a battering". Daily Record. Scotland. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Trains: Full details of ScotRail's reduced services | STV News". News.stv.tv. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Scotland Shut Down By Snow And 165mph Gusts". Sky News. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "The Big Storm: Chaos on roads & terror on runways but Scotland survives worst battering in 25 years". Daily Record. Scotland. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "School bus blown over and roads blocked by debris from 80mph storm | STV News". news.stv.tv. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "In pictures: Scotland battered by winter storm". BBC News. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Damage as high winds hit north east of Scotland". BBC News. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Ewan Palmer (8 December 2011). "UK Weather Warning: Chaos Fears as 151mph Winds Batter Scotland, Northern England". International Business Times. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- Murphey, Cormac (8 December 2011). "Ireland battered by 130kmh winds". Herald.ie. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Province is battered but escapes worst of storm". The News Letter. Portadown, Northern Ireland: Johnston Publishing. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Huge storm, high winds batter the UK with more on the way". TNT Magazine. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Scotland Hit By 165mph Winds As Twitter Dubs Storm 'Hurricane Bawbag'". Huffington Post UK. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Three rescued from floodwaters and bridge collapses in Yorkshire Dales (From The Northern Echo)". thenorthernecho.co.uk. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Wales battered by strong wind and rain as storm hits". BBC News. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Warnings as winter storm heads toward Sweden – The Local". thelocal.se. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Strong winds close Älvsborgsbron – Göteborg Daily". goteborgdaily.se. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Göta tunnel closed due to flooding – Göteborg Daily". goteborgdaily.se. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Motorists trapped in flooded Gothenburg – The Local". thelocal.se. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "BBC News – Scotland storm: Engineers battling to restore power". BBC. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "The cost of the Big Storm: Country's economy may have suffered £100m hit in one day". Daily Record. Scotland. 6 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

External links

Media related to Friedhelm (storm) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Friedhelm (storm) at Wikimedia Commons- Windstorm Friedhelm, Weather and Climate Discussion, Department of Meteorology, University of Reading