City Rail Link

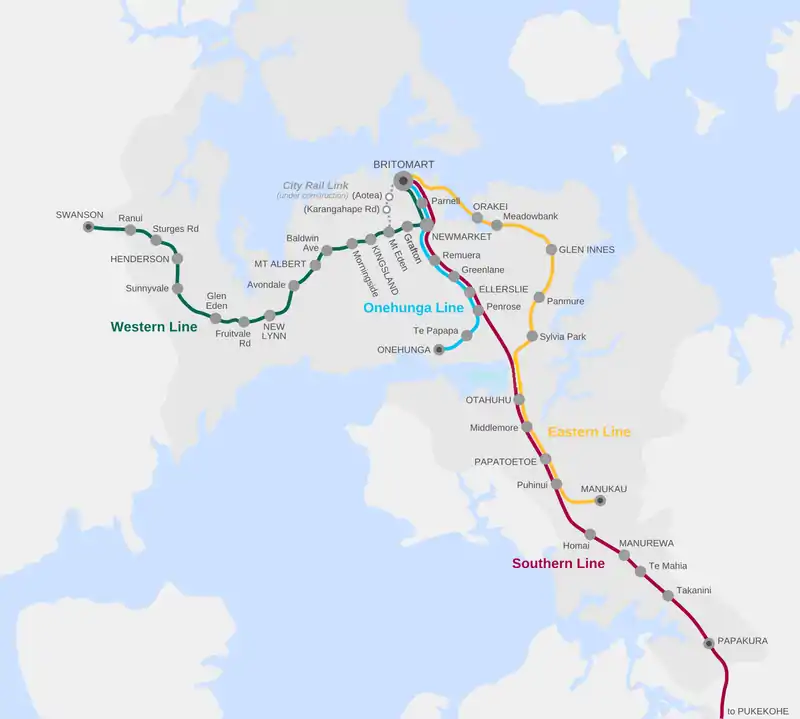

The City Rail Link (CRL) is a rail project currently under construction in Auckland, New Zealand. Former mayor Len Brown was the proponent of the $4.4 billion project, which consists of the construction of a 3.5 km long double-track rail tunnel underneath Auckland's city centre, between Britomart Transport Centre and Mount Eden railway station. Two new underground stations will be constructed to serve the city centre: Aotea near Aotea Square and Karangahape near Karangahape Road. Britomart will be converted from a terminus station into a through station and Mount Eden Station will be completely rebuilt with four platforms to serve as an interchange between the new CRL line and the existing Western Line.[2][3]

| City Rail Link | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Under construction[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City Rail Link Limited (During construction) Auckland Transport (After completion) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Central Auckland, New Zealand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Britomart Transport Centre Mount Eden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connecting lines | Western Line (Mt Eden) Southern, Onehunga, Eastern, Western (Britomart) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | cityraillink.co.nz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Commuter rail/rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | AT Metro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Transdev Auckland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | AM Class | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commenced | 2016 (Preliminary works) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 2024 (projected) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Tunnel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 25 kV AC overhead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The current project is an adapted version of previous proposals to improve rail access to Auckland's city centre[4][5] with the first proposals dating back to the 1920s. The increase in rail patronage in Auckland during the early 21st century, largely induced by the opening of Britomart Transport Centre in 2003, led to renewed interest in the scheme. The 2012 Auckland Spatial Plan highlighted the CRL as the most important transport investment for Auckland[6] and the project has enjoyed strong public support.[7][8] However, due to the significant costs and difficulties associated with a project of this size, its planning and funding have also been the subject of controversy.[9]

In June 2013, the central government announced its support for the project with a construction commencement date of 2020, four years later than Auckland Council's preferred start date of 2016.[10][11] The Prime Minister announced in January 2016 that central government funding for the project had been confirmed, allowing Auckland Council to start construction of the main works from 2018, with central funds guaranteed to flow from 2020.[12] Preliminary stages of construction, including the relocation of stormwater infrastructure and tunnelling in the vicinity of the Commercial Bay redevelopment, began in 2016. The City Rail Link is scheduled for completion in 2024.[13]

Benefits

The key benefits of the City Rail Link are intended to be:

- Turning Britomart Train Station from a terminus station into a through station,[14] allowing more than twice the existing train capacity through the core of the network (from a maximum of 20 trains per hour, to be reached in 2016, to a projected 48 trains per hour),[15] allowing trains to run every five minutes on the existing suburban lines

- Providing two new train stations in the Auckland CBD, making most of the city centre easily accessible by train rapid transit. This will boost economic activity and development in these areas and relieve projected transport access constraints

- Reducing the duration of trips on the Western Line significantly, by removing the need to deviate to Newmarket and around the east of the CBD[6]

- Allowing lines on opposite sides of the city to be through routed via the tunnel, providing direct crosstown rail connections

- Providing train capacity to allow new lines to be added to the network – including, but not limited to, other potential longer-term projects such as Airport Rail or North Shore Rail

- Doubling the number of Aucklanders who have 30 minutes duration rail access to the CBD[14]

History

1920s Morningside Deviation

Serious planning schemes occurred as early as the 1920s.[5][16] The tunnel was initially estimated at 1.75 miles (2.82 km) length and at £0.6 million.[17] In 1936, Dan Sullivan the Minister of Railways argued that the scheme – then known as the 'Morningside Tunnel' or the 'Morningside Deviation', after the proposed southern portal location – would cost approximately £1 million, with another £1 million required for the electrification of the network. He expressed doubts that the tunnel would ever pay purely from a rail point of view, though he acknowledged that there might be other benefits and wider aspects to take into account.[18]

1970s rapid rail system

The 1970s plans envisaged a loop connecting with Newmarket as part of a major rapid transit scheme proposed by Dove-Myer Robinson, mayor of Auckland City at the time. Two main stations were proposed: one downtown in the vicinity of the Queen Street/Shortland Street intersection, and a second midtown between Queen St and Mayoral Drive, about halfway between Aotea Square and Albert Park. A third city station was to be built at Karangahape Rd, but this would have been a stop on the western line only.[4] The plan was undermined by Council staff, criticised by academics and opposed by the New Zealand Town Planning Institute,[19] before finally being rejected in 1976 by the Muldoon National government, which considered it to be too costly.[20]

An alternative plan was put forward by Auckland City Council planners in 1979, involving an overhead railway from the then Beach Road railway station to the Britomart bus station (today, site of the Britomart Transport Centre). Auckland Mayor Sir Dove-Meyer Robinson noted the central government had just spent $33 million for new Wellington suburban trains (the EM class Ganz-Mavag units) and the overhead railway scheme would "cost considerably less while providing a far greater potential."[21] The Auckland Regional Authority supported the plan, although wanted to see more work done on a ground option as well.[22]

2000s rail revival / Britomart

In 2004, Auckland City Council prepared preliminary plans for an underground railway connecting Britomart Transport Centre to the Western Line in the vicinity of Mount Eden railway station[23] and incorporating three new stations: near Aotea Square, Karangahape Road and the top of Symonds Street. The project would bring most of the city centre within a short walk of a station and increase the number of people living within a 30-minute train trip of the city centre by around 370,000.[24]

The decision to electrify Auckland's rail network brought the tunnel back into focus as the key next step for developing Auckland's rail network.[23] Estimates for the project's cost were around NZ$1.5 billion (or up to $2.4 billion according to other estimates),[5] taking 12–16 years to plan and build.[25][26][27]

On 5 March 2008, Auckland Regional Transport Authority (ARTA) announced preliminary planning for a 3.5 km tunnel between Britomart and Mount Eden, beneath Albert Street and including underground stations near Wellesley Street and Karangahape Road,[28] with the Wellesley Street station, 18 m under the surface, potentially being larger and seeing more passengers than Britomart (projections of up to 7,700 per peak hour).[25] By October 2008 ONTRACK said that it had reached an agreement in principle with the owners of Westfield Downtown (later rebranded as Downtown Shopping Centre) to allow the tunnel route to thread through the foundations of a proposed redevelopment of the site.[29]

In 2009 and 2010, the discussion on the future tunnel gained much more prominence, with both candidates for the Mayoralty of the new Auckland Council, John Banks and Len Brown, making the tunnel part of their election platforms. Banks noted that it attracted cost-benefit returns much higher than many similar-sized roading projects, and would provide much enhanced, integrated access to the city centre.[30] Brown also strongly supported the tunnel, and further, a rail connection to Auckland Airport, as part of a package of measures to double public transport patronage within 15 years.[31] However, New Zealand's transport minister in 2010, Steven Joyce, warned Aucklanders not to engage in wishful thinking. The Minister's comments regarding the City Rail Link (and other rail investment), set in the context of the government's focus on delivering Roads of National Significance, has been considered politically risky – going against widespread opinion in Auckland that was in favour of better public transport.[32] After ongoing and sustained lobbying by Brown to get central government support, the nickname "Len's loop" developed.[33]

2010s designation and design

In March 2010, KiwiRail/ARTA selected a preferred route with three stations: "Aotea" (beneath Albert St between Victoria St and Wellesley St), "K Road" (beneath Pitt St adjacent to Karangahape Rd) and "Newton" (beneath upper Symonds St between the Khyber Pass/Newton Rd intersection and the New North Rd/Mt Eden Rd intersection), at an estimated cost range of $1 billion to $1.5 billion.[34] In May 2011 the Government noted that after reviewing an initial business case for the project, it was unconvinced of the economic benefits of the tunnel. Minister of Transport Steven Joyce noted that he would not stand in the way of Auckland continuing planning and route designation work – if Auckland paid for it.[5] In June 2011 Auckland Council voted to approve $2 million for planning and route protection for the tunnel, with Auckland Transport, rather than KiwiRail, undertaking the process.[35]

In March 2012, Auckland Council decided to bring forward spending from the 2012–2013 budget, in order to continue progress protecting the eventual route. $6.3 million was spent on work including geotechnical surveys, utility and building assessments, contaminated site reports and rail operations modelling and $1.7m towards providing a revised business case, requested by the government.[36][37]

In July 2012, as part of the works around designating the route, Auckland Council released footprints for four stations. This included designation space for a not previously considered station on the current Western Line, just west of Dominion Road. This station would serve as an interchange station for passengers wanting to travel east in the Newmarket direction, in case the tunnel was built without an "Eastern Link" at the southern end that would allow trains exiting it to turn east.[38] The station was later dropped by Auckland Transport and the "Eastern Link" retained in the route protection documents.[39]

In June 2013, the central government announced its support for the project, albeit with a later construction start date of 2020.[10] The government stated it would consider an earlier start date if Auckland's CBD employment and rail patronage growth hit thresholds faster than projected rates of growth.[10]

On 8 July 2013, following the 10-year anniversary of the opening of the Britomart Transport Centre, it was announced that Auckland Council and the new owners of the Downtown Shopping Centre had agreed to discuss building a section of tunnel under the mall during a redevelopment planned for 2016–17. The section would be up to 100 metres long.[40]

On 1 August 2014, Auckland Transport announced a significant design change to the project, dropping the underground Newton Station in favour of a significant upgrade to Mount Eden station. This change would save construction costs of $124 million, require fewer properties to be bought by Auckland Transport and in the long term save operational costs, with total savings being over $150 million. In addition, the change would allow Mount Eden station to be connected to the CRL, which previously bypassed it, and would separate the east–west junctions, meaning that rail lines would not need to cross each other. The Mount Eden CRL platforms would now be built in an open-air trench, similar to that at New Lynn station.[41]

On 27 January 2016, Prime Minister John Key announced in his state of the nation address that central government funding for main works construction of the CRL had been confirmed and this would allow Auckland Council to start to construct the main works from 2018, with central funds guaranteed to flow from 2020.[42] Commentary at the time reflected an opinion that this was a belated agreement to central government funding of the project by the ruling National Party, while the main opposition parliamentary parties (Labour Party, Greens and NZ First) had all been promising immediate construction timetables which were more closely aligned to the plans of the council.[43]

City Rail Link Limited

On 30 June 2017, Finance Minister Steven Joyce and Transport Minister Simon Bridges signed agreements with Auckland Mayor Phil Goff that established City Rail Link Limited (CRLL). Effective 1 July 2017, the company assumed responsibility for delivering the City Rail Link. Mr Joyce said that it was crucial that there be a single joint entity running the project and that CRLL was owned jointly by central and local government.[44] Budget 2017 allocated $436 million to the City Rail Link project.[45]

Capacity forecast forces platform enlargements

As planned, the CRL's underground rail lines will have a capacity of 36,000 passengers per hour. That figure was expected to be reached in 2045. In July 2018, revised projections by City Rail Link Ltd (CRLL) showed the 36,000 capacity will be reached by 2035 – just 10 years after it opens. Although the trains are capable of having extra cars added in groups of three, the CRL station platforms, as originally specified, would not be long enough to accommodate nine-car trains. The proposed new capacity is 54,000 passengers per hour with the station platforms to be made longer so they can take the longer trains, and for an entry to be built at Beresford Square to complement Karangahape Station's Mercury Lane entrance. The extra cost could run to the "low hundreds of millions" and would prevent a costly future two-year closure if the platform lengthening retrofitting work was carried out after the CRL was opened.[46]

Business case

One of the most contentious aspects of the CRL is whether it is economically sensible to build it. The results vary widely depending on whether certain ancillary projects are included, whether one assumes economic benefits outside purely transport effects (such as increased land value) and depending on what length of time is assumed for the benefit calculation. In this regard, Council experts have highlighted that NZ calculation methods use a 30-year cut-off (i.e. for evaluation purposes, the tunnel provides no benefit after 30 years, even though much of Auckland's earlier rail and road infrastructure already serves for much longer than that). In comparison, if using evaluation periods of 50 years (used in Australia), or 60 years (used in the UK), the total project benefits for the city rail link have been estimated as up to 6 times higher than with the 30-year time frame.[47]

The "City Centre Future Access Study" (CCFAS) was prepared by Auckland Transport and released in December 2012. The CCFAS analysed a number of different ways of improving access to Auckland's city centre and concluded that the CRL was essential, noting that bus-only investment will provide for short-term benefits but in some cases will be 'worse than doing nothing' for private vehicle travel times in the longer term.[48] In July 2013, the Transport Agency's board agreed that transport projects were to be assessed for a 40-year evaluation period, but also reduced the discount rate from 8% to 6%.[49]

Cost

An estimated cost of $2.86 billion was often quoted for the project,[50] but this cost was inflated out to the year of construction. The cost of the project in 2010 was $2.311 billion.[51] That price also included not only the tunnel link with three stations (a deep-level Newton station was later dropped), but additional trains, duplication of the Onehunga Branch to two tracks and other small improvements to Auckland's rail network. These additional items are intended to further increase the capacity of Auckland's rail network when the rail link opens, the main benefit posed by the project.[6]

In September 2016, the government formally confirmed its intention to fund its proposed share of 50% of the City Rail Link. The cost of the City Rail Link was then re-estimated to be between $2.8 and $3.4 billion, subject to tenders for remaining contracts.[52]

In mid-April 2019, it was revealed that the cost of the project had risen by more than $1 billion to $4.419 billion.[53]

Proposed timeline

In February 2012, Auckland Council published the following proposed project timeline for the City Rail Link:

- 2010 Initial study for CRL project and potential route for protection

- 2011 Review of initial study; further feasibility investigations; project team established

- 2012 Confirm route for CRL

- 2013 Notice of Requirement (NOR) and consent applications; property purchase

- 2014 Begin tender process for project

- 2015–20 Construction

- 2020/21 CRL opens[54]

This timeline will not be adhered to, as completion has been rescheduled to early 2024.[13][55]

Proposed construction methods

The City Rail Link will be constructed using both cut-and-cover and tunnel boring machine (TBM) methods depending on the location of construction. The ground through which the tunnels will be built varies between rock and soft soil, and with a variation in depth to natural ground level of between 40 metres and 0 metres.[56] Cut and cover construction will occur around the existing Mount Eden Railway Station and in the suburb of Eden Terrace, forming the junction of the City Rail Link to the North Auckland Line. North of the junction, twin bored tunnels will then extend as far as Mayoral Drive. Another section of cut and cover tunnel will then extend north underneath Albert Street, before turning east to head underneath the redeveloped Downtown Shopping Centre and into Britomart.[57] The public got a look inside the tunnels in November 2019.[58]

It is expected that the TBM will commence boring the first tunnel from a construction site close to New North Road in Eden Terrace. Once the TBM reaches Mayoral Drive it will be disassembled and taken back to Eden Terrace where it will be reassembled to bore the second tunnel.[57] In 2020, the TBM was named "Dame Whina Cooper".[59]

The line will mainly be bored through East Coast Bays Formation[60] of sandstones and siltstones.[61] It is expected that 2 million tonnes of spoil will be dug out from 2020 and it has been proposed to use it to double the single track section of the North Island Main Trunk line across Whangamarino wetland.[62]

Some landowners around Albert Street, including the Ministry of Justice which owns and operates the Auckland District Court on Albert Street, expressed concern that construction of the cut and cover tunnel would disrupt foot and vehicular traffic along Albert Street over a period of two years with several intersections along the street being closed for up to 18 months. The Department of Corrections also expressed concern that grade-separating the Normanby Road level crossing (as part of the cut and cover works at the southern end of the project) would cut off access to Mount Eden Prisons.[63]

Construction

On 7 April 2015, two construction consortia[56] were awarded the contracts to start the first construction phase of the city rail link.[64] Construction of the early works package between Britomart and Wyndham Street started in October 2015.[65]

The Downer joint venture (Downer NZ and Soletanche Bachy) was chosen to design the rail link work through and under Britomart Station and Queen St to Precinct Properties' Downtown Shopping Centre site, and construction started in early 2016.[64]

The Connectus consortium (McConnell Dowell and Hawkins) will construct the cut and cover tunnels under and along Albert St from Customs St to Wyndham St. The work started in October 2015 with the relocation of a major stormwater line in Albert St between Swanson and Wellesley Sts.[64]

Construction of these sections of the city rail link tunnels will coincide with Precinct Properties redevelopment of the Downtown Shopping Centre site, due to open by mid-2019.[64][66][67]

The Downtown Shopping Centre was closed on 28 May 2016 and by 23 November had been demolished. It will be replaced with a 36-storey skyscraper which will include a new shopping centre in the lower levels. Auckland Council and proprietors Precinct Properties struck a deal to include tunnels for the City Rail Link directly underneath the premises.[68][69]

In early December 2020, Mayor of Auckland Phil Goff unveiled a massive tunnel boring machine that would be used to drill two 1.6 km long tunnels from Central Auckland to the Mount Eden railway station as part of the City Rail Link. The boring machine was named after Māori leader Dame Whina Cooper.[70]

Britomart Transport Centre

Following completion of the CRL, Britomart will no longer be a terminal station.[71] Platforms 5 and 1 will be the through platforms,[72] while platforms 2, 3 and 4 will remain terminating platforms.

Aotea station

This station will be constructed by the cut and cover method, 15 metres (49 ft) deep under Albert Street. As originally planned, it will be 300 metres (980 ft) long and run between Victoria Street and Wellesley Street.[73]

Karangahape station

This station will be 32 metres (105 ft) underground. Original plans were for platforms 150 metres (490 ft) long. There will be an entrance on Mercury Lane, with early plans making provision for an entrance that would be added later on Beresford Square.[73] Assessments of passenger numbers in 2018 indicated that longer trains and platforms would be needed earlier, and a decision was made to lengthen the platforms so as to incorporate the Beresford Square entrance from the outset.[74][75]

Demolition of buildings on Mercury Lane began on 4 November 2019. Demolition at this site will be done in two phases, with completion expected in April 2020. Demolition of buildings at the Beresford Square site was expected to take three years.[76]

Mount Eden station

In October 2019, demolition of 30 buildings in the vicinity of this station began. This first stage of three phases of demolition is expected to be completed in March 2020.[77]

Public opinion

A public opinion poll published on 27 June 2012 found 63% of Aucklanders surveyed are in favour of the tunnel, 29% were against it and 8% didn't care. The poll was conducted by Research New Zealand.[78]

Another poll in November showed similar support amongst Aucklanders at 64%.[8] Only 14% overall opposed the building of the rail link; 18% are neutral. Support was lowest in those areas not served directly by rail. The same number of those who support it want it built as soon as possible, while 22% of supporters want it built by 2020. Over 50% of respondents wanted the central Government to contribute significantly to the cost of the project, with 30% of respondents overall supporting road tolling to pay for the project. One quarter of respondents overall supported "targeted rates".[79]

See also

Similar projects elsewhere in Oceania

References

- "City Rail Link". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- "CRL and its Benefits". City Rail Link. City Rail Link Ltd. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Stations – Mount Eden". City Rail Link. City Rail Link Ltd. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Reid, Nicolas. "An Auckland that could have been: the 1972 Auckland Rapid Rail Transit Plan". TransportBlog.co.nz. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Dearnaley, Mathew (4 June 2011). "Stuck in traffic". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Auckland Council. "The Auckland Plan". Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- Dearnaley, Mathew (14 July 2011). "Rail-loop support swamps backing for road link". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- "Aucklanders back Brown's rail plans". 3 News NZ. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Editorial. "If mayor can sell rail study, Govt should stand aside". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- "Kick-starting Auckland transport projects". New Zealand National Party. 29 June 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Rudman, Brian. "Brown hands PM an election poser". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/speech-auckland-chamber-commerce-0

- "Timeline". City Rail Link. City Rail Link Ltd. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "City Rail Link Moves Ahead". Our Auckland (Auckland Council newsletter). August 2012.

- "Len Brown: Rail link a positive after missed opportunities". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- History of Auckland City – Chapter 4 Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (from the Auckland City Council website. Accessed 7 June 2008.)

- "Auckland City Development Works – Cost to Government". Evening Post. 9 November 1928. p. 8. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- "Cost of £2,000,000". Evening Post. 29 September 1936. p. 10. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- Mees, Paul (2012). Transport for Suburbia: Beyond the Automobile Age. Earthscan. p. 27. ISBN 9781849774659.

- Chapter 2 – City Takes Control 1959–1995 Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (from the Britomart Transport Centre website. Accessed 6 September 2008.)

- "Overhead line proposed for Auckland". Rails: 16-17. September 1979. ISSN 0110-6155.

- "ARA to support city rail?". Rails: 17. September 1979. ISSN 0110-6155.

- Auckland’s rail network tomorrow: 2016 to 2030 Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine (from the ARTA, August 2006)

- Dye, Stuart. "Underground rail link feasible, says study". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- Huge underground rail station in mid-town plan – The New Zealand Herald, Friday 1 August 2008

- Dearnaley, Mathew (21 May 2007). "$1b Auckland rail upgrade powers ahead". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Following the money – e.nz magazine, IPENZ, January/February 2007

- Mathew Dearnaley (5 March 2008). "$1b loop tunnel plan to unlock Britomart". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- Tunnel deal brings rail loop step closer – The New Zealand Herald, 14 October 2008

- "John Banks: Rail loop to unlock the potential of Auckland". The New Zealand Herald. 12 October 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Orsman, Bernard (31 August 2009). "Brown vows he'll unite, not divide". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Dearnaley, Mathew (6 November 2009). "National one year on: Beware the backlash of frustrated commuters". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Manhire, Toby (11 December 2019). "The decade in politics: From Team Key to Jacindamania". The Spinoff. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Dearnaley, Mathew (11 March 2010). "Experts pinpoint best tunnel route". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- "Auckland Council presses on with rail project". TVNZ. 28 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- Auckland Council Media release, City Rail Link work accelerated

- Auckland Council Media release, Progress on City Rail Link welcomed Archived 18 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Sprawling footprints for underground stations". The New Zealand Herald. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "The CRL route". Auckland Transport. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- "Section of city rail tunnel could be built earlier". Radio New Zealand. 8 July 2013.

- "Cost down, benefits up from City Rail Link design change" (Press Release). Scoop.co.nz. Auckland Transport. 1 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- "Speech to Auckland Chamber of Commerce". 27 January 2016.

- "Fran O'Sullivan: Key's reluctant fillip two years too late". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Establishment of City Rail Link Limited". Scoop Independent News – scoop.co.nz. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Budget At a Glance" (PDF). New Zealand Treasury. 2017.

- Wilson, Simon (24 July 2018). "Auckland City Rail Link to be bigger and more expensive". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Cooper, Geoff (6 November 2012). "The value of infrastructure: multiply that by six". Chief Economist, Auckland Council via New Zealand Herald.

- "Warnings of Auckland transport network crisis". Auckland Council. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- "Economic Evaluation Manual". NZ Transport Agency. 16 March 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "CRL Updates and Resources". Auckland Transport. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Business Case – Auckland CBD Rail Link" (PDF). APB&B. p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Orsman, Bernard (14 September 2016). "Exclusive: Auckland's City Rail Link cost blows out to up to $3.4 billion". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Auckland's City Rail Link cost jumps to $4.419 billion". The New Zealand Herald. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- "Overview of the City Rail Link project, Auckland Transport Feb 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- "City Rail Link". KiwiRail. 2019.

- "Aucklands missing link". Contractor magazine. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Project delivery & construction". Auckland Transport. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "City Rail link, tunnels, public get a first look". Stuff/Fairfax. 17 November 2019.

- "City Rail Link update" (PDF). Roundabout (165): 44. September 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- "Technical Information". City Rail Link. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Fleetwood, Ben; Brook, Martin; Richards, Nick (28 November 2016). "The geotechnical characteristics of the East Coast Bays Formation, Auckland". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Auckland tunnel waste may be used to double-track Waikato rail line". Stuff. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Dearnaley, Matthew (7 August 2013). "Auckland rail plan sparks traffic fear". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- "City rail link to become a reality". National Business Review. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- "Project delivery & construction". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "Precinct-gears-up-for-Auckland-mega-project". Stuff. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "New $550m downtown tower for Auckland unveiled". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Catherine Gaffaney (22 May 2016). "Last week for shoppers at Auckland downtown mall". The New Zealand Herald.

- "Watch $850m project: preparing for NZ's biggest commercial development". The New Zealand Herald. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- "Massive tunnel boring machine unveiled for Auckland's City Rail Link". 1 News. 4 December 2020. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "CRL stations – Britomart". CRL Limited. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "CRL takes next step, but are we making enough of it?". Greater Auckland. 3 July 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Rise of the machines on city's latest underground contract – the City Rail Link". NZ Herald. 4 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Wilson, Simon (24 July 2018). "Auckland City Rail Link to be bigger and more expensive". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Stations – Karangahape". City Rail Link Limited. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Demolition begins for Karangahape Rd City Rail Link station". Radio New Zealand. 4 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "City Rail Link: demolition of 30 buildings underway". Radio New Zealand. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Kelsey Fletcher (27 June 2012). "Aucklanders back rail plans". Auckland Now.

- "64% of Aucklanders support $2.5 billion city rail link project". HorizonPoll. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

External links

- City Rail Link (Official City Rail Link project website)

- Auckland Transport Blog (City Rail Link page)

- Campaign for Better Transport Forum (City Rail Link Topic Page)