Chinatown–International District, Seattle

The Chinatown–International District of Seattle, Washington (also known as the CID) is the center of Seattle's Asian American community. Within the Chinatown International District are the three neighborhoods known as Seattle's Chinatown, Japantown and Little Saigon, named for the concentration of businesses owned by people of Chinese, Japanese and Vietnamese descent, respectively. The geographic area also once included Seattle's Manilatown.[2] The name Chinatown/International District was established by City Ordinance 119297 in 1999 as a result of the three neighborhoods' work and consensus on the Seattle Chinatown International District Urban Village Strategic Plan submitted to the City Council in December 1998. Like many other areas of Seattle, the neighborhood is multiethnic, but the majority of its residents are of Chinese ethnicity.[3] It is one of eight historic neighborhoods recognized by the City of Seattle.[4] CID has a mix of residences and businesses and is a tourist attraction for its ethnic Asian businesses and landmarks.[5]

Seattle Chinatown Historic District | |

Historic Chinatown Gate in the Seattle Chinatown Historic District | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Main, Jackson, I-5, Weller, and Fifth, Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

| Area | 23 acres (9.3 ha) |

| Architectural style | Beaux Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 86003153[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 6, 1986 |

Location

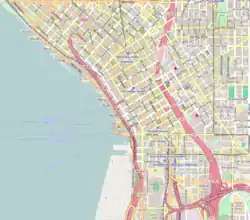

Selected locations in the Chinatown-International District

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

The CID boundaries are defined as 4th Avenue South (on the west) to Rainier Avenue (on the east) and from Yesler Way (north) to Charles Street/Dearborn (south). The CID is bordered by the neighborhoods of Pioneer Square and SoDo to the west of 4th Ave S; Rainier Valley on the east side of Rainier; Beacon Hill and the Industrial District to the south of Charles/Dearborn; and Downtown and First Hill to the north of Yesler.

Within the CID are three distinct neighborhoods: Chinatown, Japantown, and Little Saigon. The Seattle Chinatown Historic District, so designated by the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1986, is roughly south of Jackson and west of I-5, with Hing Hay Park at its heart. In the present day, Japantown is centered on 6th Avenue and Main Street and Little Saigon's main nexus is 12th Avenue South and South Jackson Street.

Public transit

The CID is served by the International District/Chinatown station on the Central Link light rail system (via the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel near 4th Ave S), and three stops along Jackson on the First Hill Streetcar: at 5th Ave S (connecting to Central Link), 7th Ave S, and 12th Ave S.

History

19th century

Chinese immigrants first came to the Pacific Northwest in the 1850s, and by the 1860s, some had settled in Seattle. Many of the first Chinese immigrants to Washington came from Guangdong province, especially Taishan.[6] The first Chinese quarters were near Yesler's Mill on the waterfront. According to Chinese oral history, the waterfront was the first Chinatown, where the Chinese dock workers lived. The influx of Chinese immigrants was slowed by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In 1886 whites drove out most of Seattle's Chinese population. However, some took shelter with Native Americans on the reservations while others came under the protection of white employers and a judge.

The Great Seattle Fire of 1889 further hindered the community. Eventually, the Chinese re-established new quarters farther inland, along Washington St. and Second Avenue South.[7] This was the second Chinatown. Land values rose, especially with impending construction of the Smith Tower, and the people of Chinatown moved again, to the present and third location along King Street. Only the Hop Sing Tong managed to retain its building on 2nd and Washington. It sold this building about 2006 in order to purchase the former China Gate building at 516 7th Ave S in the current Chinatown.

Near the end of the 19th century, Japanese immigrants also began arriving, settling on the south side of the district on the other side of the railroad tracks. Part of present-day Dearborn Street, between 8th and 12th avenues, was known as Mikado Street, after the Japanese word for "emperor."[9] Japanese Americans developed Nihonmachi, or Japantown, on Main Street, two blocks north of King Street. By the mid-1920s, Nihonmachi extended from 4th Avenue along Main to 7th Avenue, with clusters of businesses along Jackson, King, Weller, Lane, and Dearborn streets.[10]

20th century

The Jackson Regrade began in 1907; workers leveled hills and used the resulting fill to reclaim tidal flats, making travel to downtown easier. As downtown property values rose, the Chinese were forced to other areas. By the early 1900s, a new Chinatown began to develop along King Street.[7] In 1910, Goon Dip, a prominent businessman in Seattle's Chinese American community,[11] led a group of Chinese Americans to form the Kong Yick Investment Company, a benefit society.[7] Their funding and efforts led to the construction of two buildings—the East Kong Yick Building and the West Kong Yick Building.[12]

Meanwhile, Filipino Americans began arriving to replace the Chinese dock workers, who had moved inland. According to Pamana I, a history of Filipino Americans in Seattle, they settled along First Hill and the hotels and boarding houses of Chinatown and Japantown beginning in the early 1920s. They were attracted to work as contract laborers in agriculture and salmon canneries.[13][14] Among them was Filipino author Carlos Bulosan, who wrote of his experiences and those of his countrymen in his novel America Is In The Heart (1946).[15] By the 1930s, a 'Manilatown' had been established near the corner of Maynard and King.[7]

In 1942, under the auspices of Executive Order 9066, the federal government forcibly removed and detained people of Japanese ancestry from Seattle and the West Coast in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Authorities moved them to inland internment camps, where they lived from 1942 to 1946. Most of Seattle's Japanese residents were sent to Minidoka in Idaho.[16] After the war, many returned to the Pacific Northwest but relocated to the suburbs or other districts in Seattle. A remaining vestige of the old community is the office of the North American Post, a Japanese-language newspaper founded in 1902. Another is the Panama Hotel, which was proclaimed a National Treasure in 2015 with a prior listing on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.[17] Uwajimaya, originally a Japantown store, moved down the hill into Chinatown.

African Americans moved to Seattle in the Great Migration, mostly out of the South, to work in the war industry during World War II, occupying many of the houses left vacant by the internment of the Japanese Americans. They filled the empty businesses along Jackson Street with notable jazz clubs.[5]

In 1951, Seattle Mayor William D. Devin proclaimed the area "International Center" because of the diversity of people who resided and worked in the vicinity. Businesswoman and later city councilwoman Ruby Chow and others criticized the use of "international" for masking Chinese American history. The use of "International District" by the city remains controversial.[5][18]

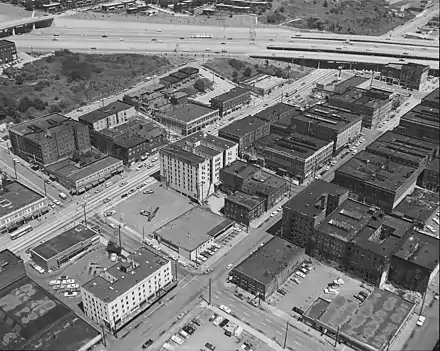

Seattle's first neighborhood advocacy group, the Jackson Street Community Council, opposed the construction of an interstate highway through the area.[5] Despite protest, many Chinese and Japanese buildings and businesses were destroyed for the construction of Interstate 5 in the 1960s.[19] Ethnic Asians formed new civic organizations (as compared to the traditional Chinese family associations, tongs and social clubs) serve needs ranging from community health, care of the elderly, information and referrals, counseling, historic preservation, marketing of the area, and building low-income housing. The construction of the Kingdome in 1972 further boxed in the neighborhood, leading to renewed protests over the community's lack of representation, including an impromptu demonstration at the stadium's groundbreaking ceremony on November 2, 1972.[20][21]

In 1975 with the fall of Saigon, a new wave of immigrants from Vietnam and Southeast Asia established Seattle's Little Saigon east of I-5. Many of these immigrants were of Chinese descent. Viet Wah became Little Saigon's anchor store in 1981, and the famous boat-shaped restaurant Pho Bac introduced Vietnamese pho to the city in 1982.[22][23]

The worst mass murder in the history of Seattle took place at the Wah Mee Club on Maynard Alley on February 18, 1983. Thirteen people were killed.

In 1986, a portion of Chinatown and Japantown was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the "Seattle Chinatown Historic District."[24] That year the Wing Luke Memorial Museum moved to 7th Avenue, a location it would occupy for two decades.

In 1999, the City Council approved the "Chinatown/International District Urban Village Strategic Plan" for the future of the neighborhood. This plan, agreed to by all major organizations in the CID, led to City Ordinance 119297. This ordinance enshrined the three neighborhoods of Chinatown, Japantown, Little Saigon and the Chinatown Historic District into one larger neighborhood with a compromised name. Since then, the often conflicting interests of development, preservation and the conversion of old buildings to low-income housing have clashed as office developments (e.g., Union Station) and market-rate housing developments are overwhelmed by drastic increases in low-income housing stock. In addition, controversy erupted over vacating S. Lane Street as part of a large redevelopment by the private business Uwajimaya. Protesters formed the Save Lane Street organization and insisted as business owners they supported re-development, but opposed vacating a public street for a private business use. After losing a lawsuit filed over the matter, the Save Lane Street group dissolved.[25]

21st century

Construction on a paifang for the neighborhood began in 2006 and the Historic Chinatown Gate was unveiled on February 9, 2008. It stands at the west end of South King Street. It is 45 feet tall and made from steel and plaster.[26]

The Wing Luke Museum moved to its present location in the East Kong Yick Building in 2008.[27]

Culture

The neighborhood hosts a Lunar New Year festival near the East Asian Lunar New Year; Dragon Fest, a pan-Asian American festival, during the summer; and a night market in early fall.[28] The nonprofit Friends of Little Saigon hosts an annual Celebrate Little Saigon event that celebrates Vietnamese culture.[29]

Landmarks and institutions

Certain neighborhood buildings in Seattle's Chinatown incorporate Chinese architectural designs such as balconies for on the second or third floors or tile roofs.[30] The neighborhood also has public art installations by artists such as George Tsutakawa and Norie Sato. Artists Meng Huang and Heather Presler installed Chinese dragon sculptures on lampposts along Jackson Street in 2002.[31]

Notable businesses and landmarks include:

- Danny Woo International District Community Garden

- Donnie Chin International Children's Park

- Hing Hay Park

- Historic Chinatown Gate (Seattle)

- Nippon Kan Theater (closed)

- Kobe Terrace

- Panama Hotel

- Uwajimaya

- Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience

Population

45.4% of the people living in the CID are of Asian ancestry. Here are the list of ethnic groups that live in the CID: • Chinese: 1,166 (22.1%) • Vietnamese: 274 (5.19%) • Filipino: 180 (3.41%) • Japanese: 122 (2.31%) • Korean: 108 (2.05%) • Indian: 78 (1.48%) • Taiwanese: 14 (0.27%) • Other: 53 (1.01%)

See also

- Festál at Seattle Center, a series of festivals celebrating the culture and contributions of Seattle's various Asian American and other ethnic communities

- History of Chinese Americans in Seattle

- History of the Japanese in Seattle

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- "Filipino Community". Seattle Chinatown–International District Preservation and Development Authority. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- "2010 Census Data". United States Census. 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "International District". Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. City of Seattle. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- "Seattle Neighborhoods: Chinatown–International District – Thumbnail History – HistoryLink.org". www.historylink.org. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Ng, Assunta (September 26, 2013). "BLOG: Thinking big, that's their motto". Northwest Asian Weekly.

- "Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage: Seattle Chinatown Historic District, Seattle, Washington". National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, ed. (2014). "Chinn, Wing Sam". Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-295-99348-5. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Lei, Owen (July 17, 2011). "Seattle man champions changing a century-old street name". KING-TV. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

City ordinance 4044, enacted Dec. 23, 1895, changed the name "Mikado" to Dearborn Street as part of a city-wide plan to standardize street names in a booming urban area. Section 276 of the bill stated, 'That the names of Alaska Street, Mikado Street, Modjeska Street, Cullen Street, Florence Street and Duke Street, from Elliott Bay to Lake Washington, be and the same are changed to Dearborn Street.'

- Takami, David A. (1998). Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle. United States: University of Washington Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-295-97762-0.

- "Seattle's Chinatown/International District". Wing Luke Museum. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Building and Architecture > Wing Luke Museum". Wing Luke Museum. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- Mejia-Giudici, Cynthia (December 3, 1998). "Filipino Cannery Workers". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- "Filipino Cannery Unionism Across Three Generations 1930s-1980s". Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, University of Washington. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Mejia-Giudici, Cynthia (February 14, 2003). "Bulosan, Carlos (1911?-1956), Writer". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- "Japanese American Internment during World War II". Friends of Minidoka. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Broom, Jack (July 26, 2015). "Seattle's Panama Hotel deemed a National Treasur". Seattle Times. Seattle Times Company. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- "Name feud clouds opening of library". The Seattle Times. June 11, 2005. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Crowley, Walt (1998). "Chinatown-International District". National Trust Guide Seattle: Americ's Guide for Architecture and History Travelers. New York City: Preservation Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-471-18044-0. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Tsutakawa, Mayumi (July 8, 1999). "How The Kingdome Spurred The Asian-American Community's Coming Of Age". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Kingdome Protest and HUD March". The Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Asian Food Market, Online Specials, Grocery Store | Viet-Wah Markets". Asian Food Market, Online Specials, Grocery Store | Viet-Wah Markets. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- "A culinary pho-nomenon: The history of pho in Seattle". MyNorthwest.com. November 4, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Lowe, Turkiya L.; Taylor, Quintard. Recommendations for National Register Designation of Properties Associated With Civil Rights in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington (PDF) (Report). National Park Service. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

Rainier Heat and Power Company

- Jacklet, Ben (July 15, 1999). "The Great Mall of Chinatown". The Stranger. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- "Historic gate provides another link to Chinatown's roots". seattlepi.com. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- "Building and Architecture > Wing Luke Museum". www.wingluke.org. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- "CIDBIA Events". cidbia.org. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- "Events". Friends of Little Saigon. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Poe, Nathan. "Seattle International District--Seattle, Washington: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Map: Seattle Public Art. Seattle: City of Seattle Office of Arts & Culture. pp. 22–23 – via http://www.seattle.gov/arts/experience/maps-and-apps.

Further reading

- Bulosan, Carlos. America is in the Heart (1946)

- Chew, Ron, ed. Reflections.

- City Ordinance 119297. www.seattle.gov

- De Barros, Paul. Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle (1993)

- Filipino American National Historical Society. Pamana I. Seattle, Washington.

- Filipino American National Historical Society. Pamana II. Seattle, Washington.

- Filipino American National Historical Society. Pamana III. Seattle: 2012.

- George, Kathy. "Seattle's Japantown remembered" (Archive). Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Sunday November 21, 2004.

- Ho, Chui Mei. Goon Dip.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Seattle/Pioneer Square-International District. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to International District, Seattle, Washington. |

- Official website of the Chinatown-International District

- Seattle International District description from the National Park Service

- International Special Review District from the City of Seattle

- Seattle's Asian American Movement, a multimedia collection of resources on the International District Preservation Movement and the Kingdome protests by the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

- International District from Seattle Post-Intelligencer

- Guide to the International Special Review District Records 1973-1997 from the Northwest Digital Archives